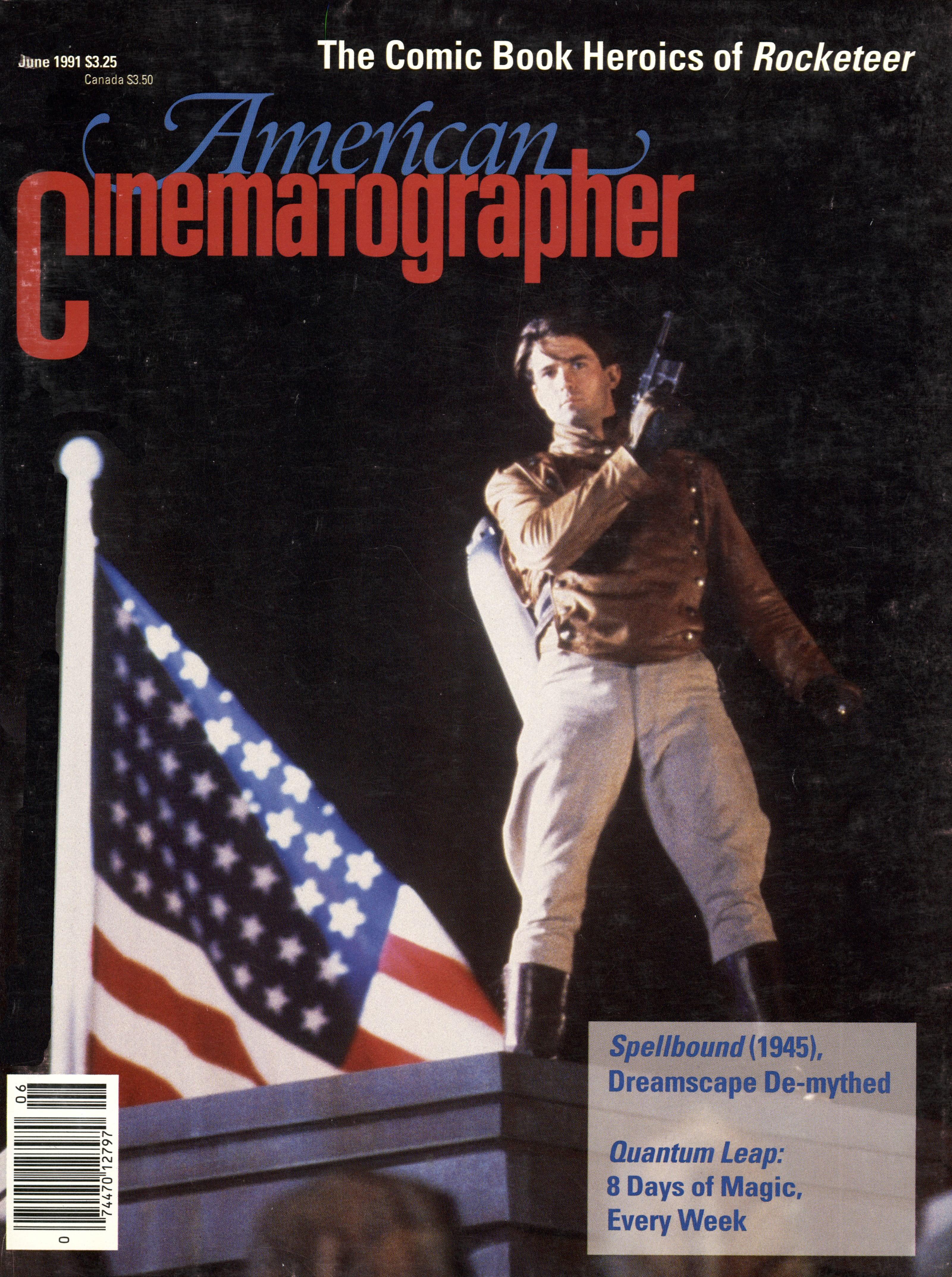

Television Cinematography Takes a Quantum Leap

Michael Watkins, ASC talks about his journey from architecture student to the man responsible for the look of NBC’s inventive sci-fi series.

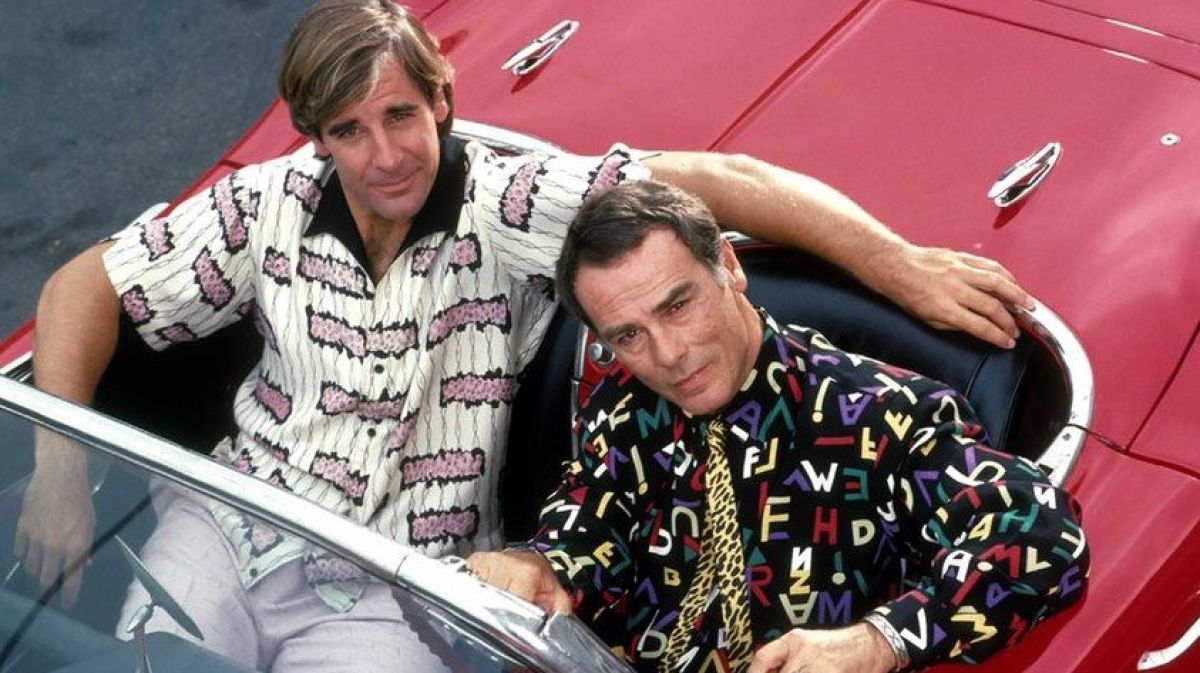

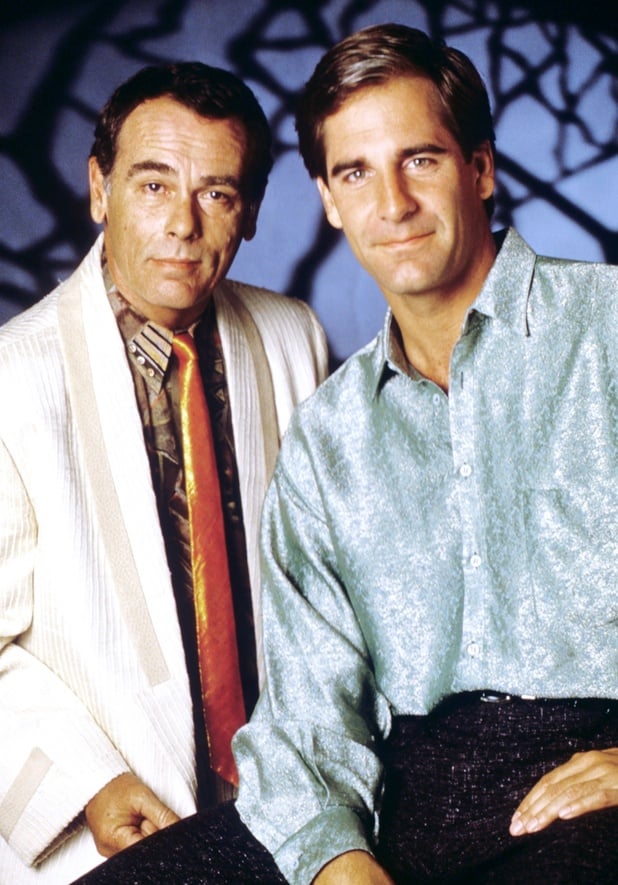

Quantum Leap is a cinematographer's dream — and nightmare. Every week, a new situation arises, in a new time period, bringing with it new sets, styles, opportunities and demands on creativity and problem solving. The story: Sometime in the near future, an experiment in time travel goes awry, leaving one of the scientists—played by Scott Bakula — stuck drifting through the past. The other scientists found a way to send some help in Admiral Al Calavicci — played by Dean Stockwell — who manages helping his partner out of the various jams he finds himself in. The trick: He himself cannot travel through time, but his holographic image can. The result is a television production that can never resort to the status quo — there isn't one.

Before entering the episodic television realm and finding his niche on Quantum Leap, Michael Watkins, ASC made a career's worth of high end television commercials, at first as a grip, then later as an operator and finally a director of photography. "Lee Lacy and Dick Snider were incredibly popular at the time for commercials," he says, "and they started my career in commercials. They were very advanced for that time. What they taught me was not so much technical but an endurance of feelings. These were extraordinary spots — I worked on Boeing and Schlitz, and Coca-Cola and Olympia Beer, Cadillac and United Airlines. They were wonderful campaigns, and I learned a lot.

"What we do isn't brain surgery, but it takes a certain command of visual grammar to do it right. I was very fortunate to work with some incredibly creative and unselfish people."

Watkins had photographed a couple of features (Fighting Mad, The Glitterdome) and the first few shows of Scarecrow and Mrs. King when he was hired onto Almost Grown, where he stayed for 13 episodes. Don Belisario saw the show and convinced Watkins to come aboard on Quantum Leap. Watkins enjoyed his commercial work, but relishes the opportunity to apply his skills in the service of dramatic storytelling.

Everyone has his or her story — "How I got into the film industry" — and Watkins is no exception. He was born into a film family, but he came into his position as a top-flight director of photography reluctantly, at least at first. His father worked as a timer at Technicolor in Hollywood, later became an editor, and eventually directed and produced. Watkins grew up at his father's elbow on the editing bench, but used a baseball scholarship to study architecture at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. When his knee was injured, Watkins took a semester of political science at Cal State Northridge. A call came for a 30 day job on a film in the Arctic. Nine and a half surreal months later, the young architect came home to find that he was making a living in "the business."

"We were doing a Disney film up there with 12 polar bears from Germany," Watkins recalls. "No one could speak German, and of course the polar bears couldn't speak English. It was Old Yeller with an Eskimo kid and a polar bear. I remember the local Eskimos always wanted to watch two movies: Nanook of the North, and for some unknown reason, That Darn Cat starring Dean Jones. It was a very strange experience. I can still quote from that movie.

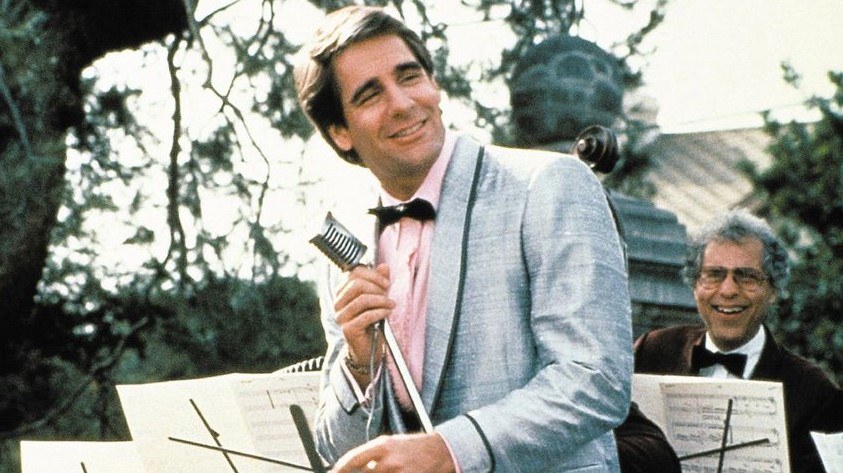

"Quantum Leap is an anthology in that there are no standing sets or a standing story idea," explains Watkins. "We work from the '50s to the '90s. It's always different every week and that's a real pleasure. It also means that the amount of work we do is staggering. The diversity in the work, with all the combinations of lighting and lenses and style, is extraordinary. It keeps you really fine tuned — you're really ready to go and shoot anything."

Watkins relishes the creative freedom he is allowed on the show, and credits much of the success to the show's stars — Stockwell and Bakula. "I work with two extraordinary actors. Both of them would rather that we push for the look of the story than worry about their eyelights. And of course I couldn't do it without my crew," he smiles. "They're the specialists. I allow them to do their jobs, and I try to blend in where I have to."

It's a good thing, because the schedule is murder — in the rushed world of television, most shows have standing sets and recurring situations where a director of photography can simply make fine adjustments to an established style — say in a courtroom, or a police station.

An episode of Quantum Leap is finished in eight days. For nine or ten months, with virtually no days off, the grueling schedule continues. "At the start of the year, you start getting tired by five or six in the afternoon, and you think about it. After a while, you get into a groove and forget how outrageous it is. But by the end of the year you're tired at nine in the morning. You're definitely toast.

"Hopefully I see the script five or six days ahead of the episode" Watkins relates. "We read it for content and concept, knowing that it will probably be trimmed. But it's good that we read the broader script — we can see what the writer is getting at."

The next step is a location scout — whoever has time attends — and a follow-up "head session" with the director, usually one of a rotation of four. "We meet and talk ideas, and figure out what we need. All the directors are a little different," says Watkins. "Some guys are better with certain things. When we scout, we send out a video camera, so we have tape of what the locations are, and we always try to shoot at the time of day that we'll use it.

"In a way, I pity the episodic director," reflects Watkins. "He comes onto a set, and he gets onto this horse, so to speak. Has the last jockey whipped it to death? Is the horse in full stride? They walk in blind. It helps that we rotate four or five directors, so the crews and the directors are at least familiar."

As on most episodic television shows with a rotation (or ever-changing) directors, the director of photography is counted on to provide continuity — and more. "The director of photography in episodic television is the mainstay. You're the elected mouthpiece to every link — the point where all the tumblers fall into place."

"Getting what I want" for Watkins (since more time is out of the question) means equipment and technology. Keeping up with changes can be difficult when most of one's waking hours are spent on the stage.

“I don’t want to offend anyone, but the long and the short of it is that the cinematographer does a hell of a lot more work in terms of pace and management of the show than is credited. They conduct eight day schedules, maintain quality control, keep prices down. It’s worth it for me, on this show, because it’s a trade-off — I pretty much get what I want, and I get it done on time.”

"You have to keep real open, and be humble enough to ask questions," he states. "Things are changing every day, and you can't stay at the front of everything. With the new films, you can light as you see. And if you can keep all that equipment at your disposal — lighting and lenses and filtration — you can do some incredibly delicate things.

"The Eastman 5296 stock is unbelievable. It is a mind-boggling experience dealing with this new stock. I'm grateful I survived in the business until the 96 came out," he enthuses. "The 94 — the inherent quality of that stock is that the overs hold up no matter where you go. You could be working at 2.8 and look at an 11, and you're going to hold it. The problem is you can't go the other way. The 96 goes in the other direction. It's just a style, a matter of taste, which one you prefer. I like the 96 and the 45. That's where I find my gift."

"The 45 is interesting — it's so perfect, it's so positive. The blacks are so true. With any stock, it's a like a pilot flying by stick and experience. If I'm in really dark heavy tones, sometimes I'll reach in for that little bit and let the sun spots pop. I have to be careful that I don't give it too much advantage in the rating," he says.

"The 96, on the other hand, I very seldom rate at the recommended 500 ASA. I really use the speed — I often rate it at 1000 ASA or more. I'll register readings at 500 and make all kind of stop corrections, and I work it all within my mind. If we're getting inside to do closeups, I may make adjustments with the lights, but those are cosmetic things I want to do with the light, not because of the film."

Once the image is on film, it begins its long journey to broadcast. Watkins follows the image as closely as possible, squeezing quick consultations with the post people into his already manic schedule.

"We're starting to finish more and more on the negative now, which I think is a good look" he continues. "The low contrast prints have a real value, but we edit and finish on LaserDisc right now — right from negative to LaserDisc. There's something terribly traumatic about a cameraman not being able to go see his dailies on the big screen, but on the other hand, watching it on LaserDisc is really something. You just can't believe how beautiful some of these things look."

Watkins establishes a relationship with the transfer people before the season begins, and tries to solidify it during the first three or four shows. "It's difficult for that person, because they're trying to satisfy their sense of value, as well," he says.

In special situations, Watkins works with the transfer people towards a certain effect. In one episode, which took place for the most part in a mental institution, Watkins wanted a somber, rainy look outside the windows. "We needed this confederate grey, foreboding weather outside, but on the inside, in the corridors, we wanted to keep a real institutional tungsten quality—the time period was 50s. In this case, I just asked them to leave the dailies alone, let them come off just like they are, without any electronic balancing. We saw then that the windows were just a little too blue, made our adjustments, and in the next seven days everything was just perfect.

"You have to understand," Watkins explains, "I'm a film man. I don't want them correcting my negative. My negative is my only control. If I start giving that away, I'm a goner."

The show is "babysat" all the way through the process to maintain integrity. "One of our post people is always there, and I talk with those people constantly," Watkins continues. "When they go to spotting sessions, when they go to the finals, the corrections, whenever I can find time to talk to them. Even a quick call on the phone is greatly appreciated: 'Did you want to have it look this way or that way?' I much prefer that to somebody taking a guess."

The process, though fraught with uncertainty, produces a show which is visually as distinctive and consistently imaginative as any on television. Watkins' approach to photography implements the slick commercial styles as well as the elegant pictorial style of feature films.

"I've never been a fan or a shooter of field lighting," he states. "I don't like bringing the whole set up to 5.6, unless that's what's called for, which is rare. You try to focus attention on what's important in the scene. We use dimmers a lot for that, and also, the length of the lens has a lot of impact. We take the finder, put the appropriate lens on and block that way. Then I like to watch the actors run the scene. When you let them move around, they're going to find their way and you'll see what their input is — where they put the emphasis. They expedite your work, and you can help them by accenting moments for them."

Watkins recalls specific episodes and unusual approaches taken therein. His descriptions sound more like an elaborate feature than a television production.

"One particularly good episode, directed and choreographed by Debby Allen, is about a dancer who is deaf," he says. "She picks up the vibrations of the music through the floor. We wanted a certain look, with lasers. We gathered a bunch of mirrors, broke them, and glued the pieces into a pyramid on a piece of plywood. We hung this thing in the grids, hit it with the Xenons, and it was a real effective light. It brought up the key and dispersed light, and lots of shards of light came pounding in. I bounced light through them and also swept light across it. For that '60s disco time it really hit the mark.

"The set was the whole width of Stage 17 and probably 50 feet deep, and it was a rehearsal hall. We had maybe 60 dancers, and we did a great shot with the Louma crane — a 360 degree shot, moving through rows and rows of dancers, and the room was filled with mirrors. It was very nice.

"Another thing I'm proud of is the handheld work that we do. Steve Peterson and I have been doing handheld for 19 years. A recent show featured a late '70s, Kiss-era rock 'n' roll motif, and we shot a concert sequence at the Long Beach Civic Auditorium. We did a lot of handheld there, and they're putting three of those songs on MTV.

"In the episode about VietNam, we handheld 99% of the show. We handheld a 250mm lens, did all the action, running along with a Panaflex on my shoulder — with a video tap. It was arduous. There were two shots in that show that were not handheld — one of which is one of my favorite shots."

The shot comes at the climax of the show, as the characters are running towards the waiting helicopter. It's a shot we've seen often on television and in features. Watkins' description helps explain why cinematography is such an important part of Quantum Leap despite the tough schedules.

"We used a 400mm lens, real late day, and we ran up to about 36 fps. You see reeds and tall grass, everything sitting there absolutely perfect, with that softness as it moves. Then abruptly you hear fire — all you hear is the BAM BAM BAM BAM going off —and they come running into the frame, just a little over-cranked. Suddenly, the reeds in front of us just lie down, horizontal, and the helicopter lands. We're looking straight through the door, and the guy is blasting away with his gun. You can see the shell casings ejecting, a little bit off speed. The characters come running right into a head shot, and the helicopter lifts up and rolls off, and we follow it out.

Focus was not a problem — and that's the gift of having a guy like Steve Peterson. We laid a lot of white board down, and we hit some gold reflectors, let the sun do a lot of hits, and we just walked away from it. I was probably working at around a 4 or a 5 stop, with the 45 film, rated at around 100. The light was not a problem — I even had nets on, to get the little bit of star effect, from the sheen of the grass.

"It's a treasure of a shot for me, and how we got it at sunset and everything makes it even more amazing. The chopper landed 20 feet from us, and he just came in out of nowhere. It's a real dramatic scene."

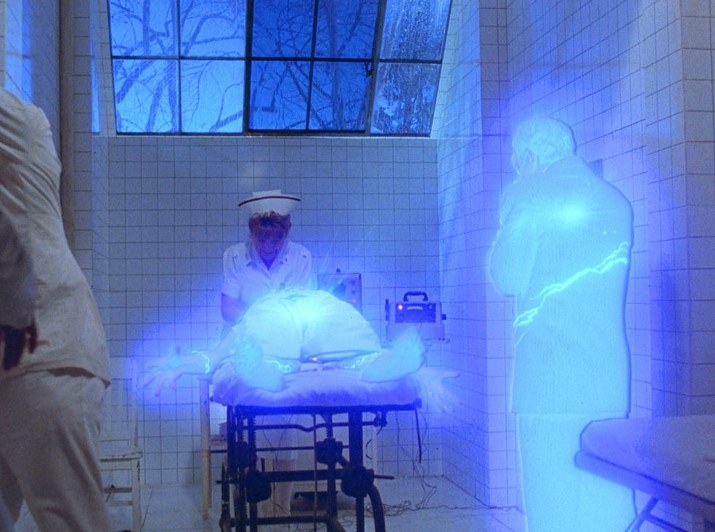

A big part of the show's success is the special effects sequences which draw the audience into the suspension of disbelief. The titles and straight opticals for Quantum Leap are done by Howard Anderson Company, but the signature "leaps" and other work are handled by Apogee, Inc. Certain episodes call for more effects work, but each show requires Stockwell's entry through the white door, his appearance in the show as a "holographic image," and Bakula's leap in and leap out. Apogee's part of the leaps usually comes in during postproduction, the visuals being done with traditional animation, and then optically combined on film. The "holographic image" is accomplished mainly through bluescreen techniques.

Roger Dorney supervised the optical department at Apogee for more than 12 years, contributing his talents to innumerable productions of every size and scope. When he became effects supervisor for Apogee's work on Quantum Leap, he found less and less time to contribute to other projects. "The show is very time-consuming," he says, "mostly because everything has to happen in a very short period. It's a lot of fun, but it's not a half-time job."

Dorney and Apogee's producer Denny Kelly get involved from the start of each episode, at the pre-production stage. "They start by laying out what they want to do for a particular show. Television being what it is, sometimes the scripts are still wet when I get them. We talk with the director about ways of accomplishing that, maybe give them some suggestions, and then choose the way that's right in terms of the story and the budget. Once production starts, we're out there supervising the plate shoot — the bluescreen backgrounds — and then marrying that up through video assist.

"The pass-through has always been done bluescreen, so far" relates Dorney. "There are other ways of doing it, and actually there'a another show on television now that does something similar using rotoscope. The problem with rotoscope is that to be effective, the shot has to be short. Otherwise you starts to see the drawing, no matter how good the work is. Hence we use blue screen, which also gives you a little more flexibility further down the line. The audience seems to like the effects, so we try to stretch them to about four or five seconds.

"We have a setup that we keep over at Universal," Dorney continues. "Quantum Leap has a stage and half allocated, and we just have a screen that we keep hung up there, draped. Then we have some special bluescreen lights — fluorescents that Apogee came up with — that we have stored, and some floor lighting that is shuttled around. We can just go over there and be up in an hour or so.

"Sometimes the director is there and sometimes he's not, but Dean Stockwell is usually the person on the blue screen, and of course he kind of directs himself. I'm out there as a technical director as much as anything else — I keep us all out of trouble. Michael is sometimes there, and if not he's usually on the stage next door. We bounce things off him to ensure continuity. In my mind, the director of photography is the one bit of continuity all the way through the show," Dorney opines.

Watkins takes great care in the pass-through and other effects scenes, knowing their importance to the show. "I use the same camera and lenses to shoot the blue screen and the plates," reveals Watkins. "The pass-through stuff is a real mathematical thing, and lighting those can be a little bit tricky. We try to include elements which contribute to the believability — sound and angles, anything that helps. We put the blue screen lights between 8000 and 9000 degrees Kelvin. Then we take the 96 and we rate it at 250 ASA instead of the recommended 500. For some scenes, we rate it up to 1200 to 1500, depending.

"We use a lot of colors to match it out — the normal things with yellow filters to avoid blue spill — and that's a real technical, ABC kind of thing," Watkins continues. "You follow your book, you make sure you know where you're going, and you trust yourself."

Dorney uses video technology to facilitate the process, a trend making its way throughout filmmaking. "We employ a company called Video Assist to record the background as we shoot it. We'll have someone walk through the motions, and when we go on to the blue screen to shoot the foreground elements, we use that video record to compose to, for size as much as anything else," he explains. "On the background plate shoot, we take measurements and layouts too, but when we get to the bluescreen stage, we invariably have the video in front of us, and we adjust to that. Stephanie Powell is Video Assist's operator, and she's very helpful.

"In the dark ages, before video assist, you'd get the background, have a guy stand there as a reference. Then you'd go to an animation stand, pencil sketch where he's standing, and then mount that in the viewfinder, and then compose to that once you got to the blue screen stage. Of course that's only one frame, so you couldn't be real accurate with movement. The video assist is really great that way. It's a reference, a way of catching it if there's something wrong."

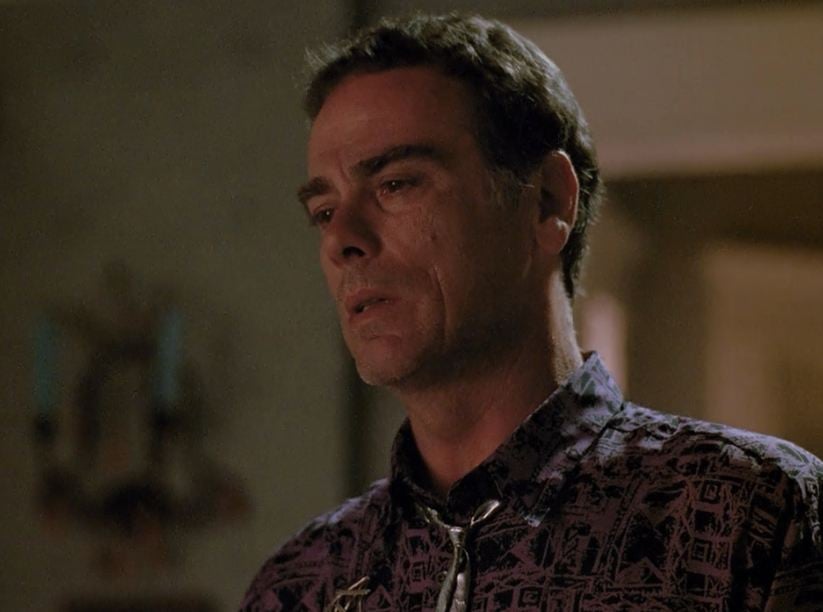

The story logic of Quantum Leap calls for Dean Stockwell's character to be in the future while his holographic image travels to the past to meet up with Scott Bakula's character. This conceit raises some interesting questions in terms of reactive lighting.

The decision was made that surrounding light and shadows should not affect Dean's image," says Dorney. "They try like hell to stick to that, especially the shadows. Not casting shadows is one thing, but not having shadows fall on him — that's the tough part. Therefore, when we shoot the effects work, if things don't match, I've got an easy out — he's in the future, he doesn't have to match. The problem is if we just shoot him all lit up, under optimum blue screen conditions, he looks like a cut out—and it looks like an effects shot."

Like any effects person worth his salt, Domey immediately envisions his worst nightmare — thousands of viewers across the country pointing to their televisions and saying, "Hey, there's an optical!" To solve the problem, a compromise is struck.

"We kind of go halfway. We try to match the lighting that's in the background, and if there's reactive lighting — we've had fire, cop car lights, lightning — we will hit Dean with appropriate reactive lighting, but not as intense. It looks silly if the scene gets real bright, and he stays dark. So we bring it about halfway. He's still set off from the scene, in a kind of supernatural way, but he doesn't look like a bad matte shot."

Although Michael Watkins once aspired to architecture, he doesn't regret the career he ended up with. "I think there's a lot of storyteller in a good photographer. You do it visually. I think it's a real gift to be able to have the job, to be able to accomplish that. It takes a lot of work, but it's very gratifying.

"Your job is to keep the story going subliminally, emotionally, visually, texturally, all in a subtle way. You have to embellish every point of the story. You have to be hidden at times, and at other times more obvious," he advises.

"Any little thing that you can do — the curtain blowing on the set — any piece of detail — is real important. I think from commercials I learned to appreciate detail. We dealt in tenths of a second. I like to work with that kind of detail, and all the little innuendos involved. I think it makes my work better — and it makes it a lot more fun."

Michael Watkins was involved in 61 of the first 84 episodes of the show (which ran for 97 episodes total). Watkins shot 60 of those, pulling double-duty as director on five. The lone episode he directed which he didn't shoot himself, was shot by the late Bradley B. Six, ASC.