Terminator 2: Judgment Day — For FX, The Future Is Now

In a recent interview regarding ILM's extraordinary work on Terminator 2, Dennis Muren, ASC takes a knowledgable look into the future of motion-picture visual effects.

This article originally appeared in AC Dec. 1991. Some pictures may be additional or alternate.

“Visual effects is a different world than it used to be,” muses Dennis Muren, ASC. “It’s in a rather dangerous transition time, as it was just after Star Wars. A lot of people out there were saying that they could do the Star Wars stuff and they really hadn't done it yet. The work wasn't coming out as well because it seemed easier than it really was. A lot of little motion-control companies were set up, and for about three years people had to learn how hard it was to use it effectively."

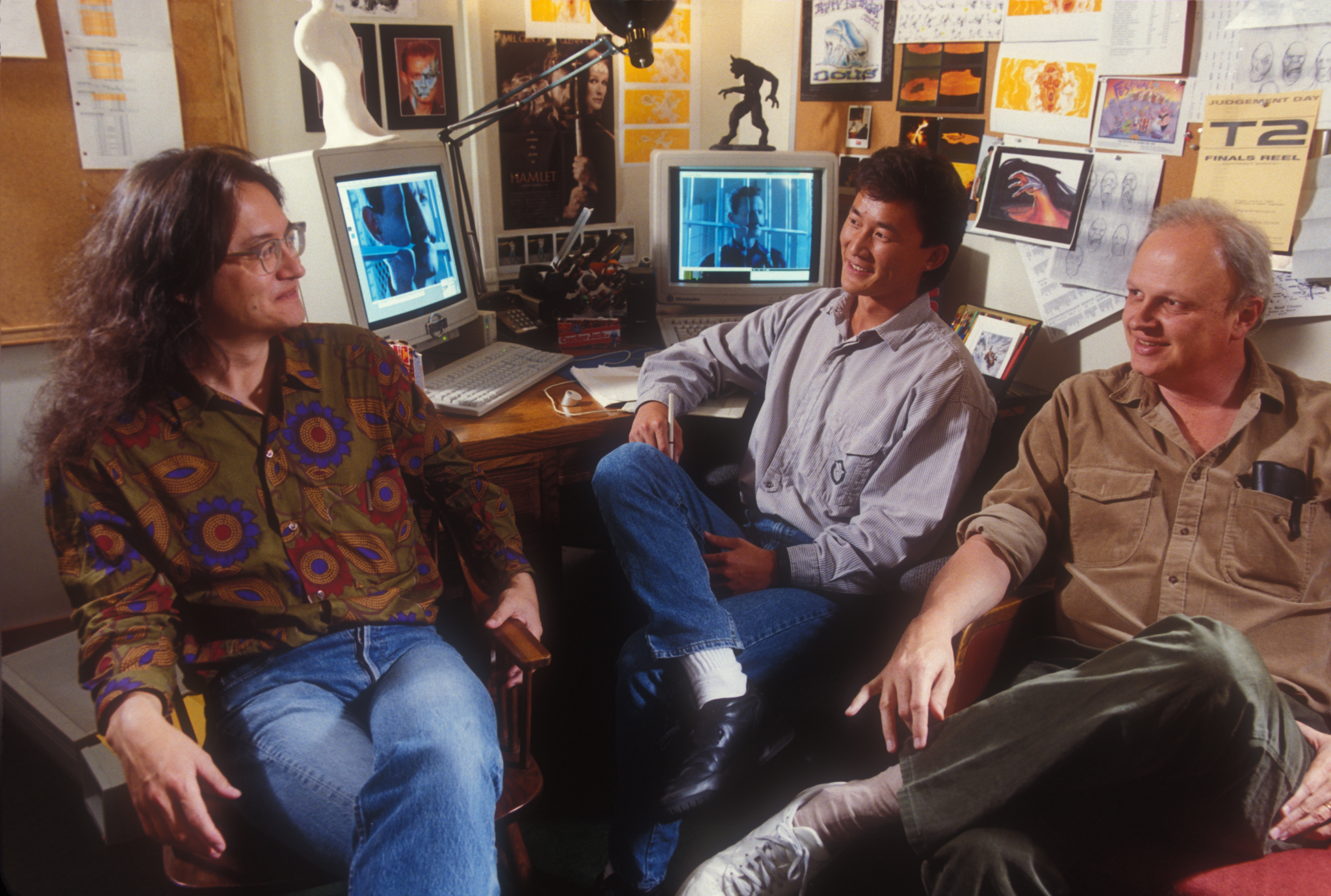

Muren was one of the visual effects experts whose skills were showcased in the trail-blazing Star Wars saga, placing him among the top players in the field. More recently, he and a hand-picked crew at Industrial Light & Magic contributed many highly sophisticated effects involving computer graphics and digital compositing to Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

"I'm worried now that it may happen again with computer graphics, and also things like wire removal and rod removal, which are going to have a big impact on the industry," Muren adds. "That stuff is still not easy to do and you have to be careful or else you're going to get stuck later on with something that will look pretty fakey."

"With T2, we started out with around 45 or 50 shots. In this picture, audiences are seeing two really important things that are separate. One is a CG [computer graphics] character that was never built but that we created, animated and gave reflections to. The other thing is the digital compositing. If either of these were removed, the work wouldn't look as good.

"When we started the project we didn't know if we could do it," Muren recalls. "Jim [Cameron, the producer-director] had his fingers crossed and I had traditional backups for almost everything, so that if something was not going to work there would still be some way we could tell the story and not get a horribly embarrassing shot into the show. We began gearing up and hiring more people — we had to more than double the size of the department. A lot of people wouldn't come to work here because when they saw the storyboards they didn't think it could be done. We had get to people from Europe, New Zealand and Canada.

"The point is that this show wasn't a sure thing at all. At the start of this picture — just a year ago — the same people who are now saying they can do it were saying, ‘You can't do it.’ We took a big risk and managed to pull it off, but at the start I thought we were only going to be able to get about a third of the shots and that the rest would have to be composited by the old techniques, but we managed to get them all digitally."

The advantages of digitization of images involving computer graphics have proven to be greater than was anticipated, judging from the results seen in T2. "Digital compositing means that the CG man is put into the shot with no artifacts at all — the grain pattern matches from foreground to background," says Muren. "The digital stuff has just come together within the past year. A lot of people are doing digital stuff, but we are trying to copy a 35mm frame, to get high resolution so that if we cut it into a picture you can't tell the difference."

Muren recollects something a fellow cinematographer said recently at a technical meeting. "Allen Daviau [ASC] asked, ‘When can I see any one shot that has gone through the digital world and back into film again?’ There have been a few: about six shots in Back To the Future III, two in The Abyss, and we did one in Young Sherlock Holmes about eight years ago — the stained-glass man." He referred to a sequence in which a figure in a stained-glass window came to life, leaped to the floor and attacked a man with his sword. "One shot in there was actually a digital comp," Muren added.

“It has been important for our shows that my background has not been in computers. By being a regular cinematographer and also being interested in matte painting and effects, I know when things look real and when they don’t.”

— Dennis Muren, ASC

"It has been important for our shows that my background has not been in computers. By being a regular cinematographer and also being interested in matte painting and effects, I know when things look real and when they don't. The computer people come to it from a video point of view; they're not as familiar with the end result and how critical it is in a major motion picture. On Sherlock, the guys did a terrific job, and one of my biggest jobs was just saying 'It's not real enough' and guiding them to what was missing. The little pebbles in the stained glass were perhaps not concave enough, or the little dots looked to be the same size, or the edge of the glass didn't have enough mixture of soft and hard-edged curves. I remember saying that if I were a kid I'd go out and buy a computer and learn it, which is what I did with cameras when I was young."

Muren does more than talk about the idea. "I took a year off from work and bought a high-end Macintosh and a bunch of programs to learn this from the bottom up, which you can't do when you're working," he reveals. "I went through a lot of basic stuff like understanding file transfers and the mouse and all the fundamentals of being comfortable with a computer and input devices. At the same time, I was looking into the digital comping that was going on here at ILM — looking at film recorders, input devices for digitizing film and software for compositing. All the time I was thinking that it's time to get the image processing stuff out of the research-and-development lab and into the production at ILM to see if it's ever going to be a useful tool, because, if not, then we shouldn’t be counting on it for shows.

"Around the same time that was going on, other people were looking at this sort of thing and it all came together rather quickly. So when T2 came along, I was there with a lot of optimism that we could do the CG and also get the image processing tools into a production level where we wouldn't just do six shots a year — we could do a lot of shots. In this one year alone, we're going to have maybe 175 digital composites between Hook, Memoirs of An Invisible Man, T2, Hudson Hawk and The Rocketeer. It was just a matter of focusing things."

One disturbing aspect was that no standards existed for the technique. "People were saying the resolution had to be 2,500 lines or more," Muren reflects. "By coming from a film background, I could look at the screen and say, 'That's good enough. Let's not take it farther if we don't need it, and if there is a trade-off, then I want to go for the minimum necessary to do the job. Then we can get more tests done and finish more shots.' There is a trade-off: the more resolution, the slower everything runs. If they look good enough to me, then I'll say they're good enough for the film."

Muren believes that the adaptation of CG-digital by ILM promises to simplify the decision making process. "Once we're not in the lab looking at 10 different possibilities, and we know the one way we're going to go, then we can gear up for it and do it. It's as if Kodak didn't sell you film but sold you the clear base and all the chemicals. There are a lot of different ways you could do it. Some guy might say 'I want this because the saturation is better,' and someone else would say 'No, I want this because it's sharper,' and someone else would say 'No, I want to do this because it's a faster speed film.' So, when everybody is spinning around in a circle, what you need is somebody to say 'This is what you're going to get and you have to work around it.'"

The approach to CG work, Muren admits, differs greatly from what effects artists have become accustomed to in the past. "In traditional effects, if you set things up and make a test shot, it's pretty easy to make changes. If the colors aren't right, just repaint it; if you want to change a model, just pick it up and redesign it. So our mindset is that you refine and refine and refine and you can make pretty large leaps each time. One thing I've found, on T2 especially, is that in the CG world, what you see the first time may be 90 percent of it. To make a change is a big deal and it's going to take a long time, because a lot of what you get is a result of the software and the interaction of the person to the software. It's not in its infancy anymore, but it's still pretty juvenile and there's not nearly the flexibility that there is in working with models. If you don't like it at the beginning you have to watch out or you will use up your time and budget trying to fix too many things. You've got to have the animator who is working on the shot understand very clearly exactly what you're trying to do and then be prepared for what you get. It's not going to quite be it, but it'll probably be good enough. It's just a different interpretation. The public can't tell the difference as long as it's still up to quality."

Although the question of whether or not to use storyboards is sometimes hotly debated among directors, they are considered indispensable in special effects production. Effects storyboards are more detailed and intricately planned than is customary in general production, and the ones prepared for T2 were no exception. "We followed the storyboards pretty much to the letter," Muren says. "Once you're in this computer world you can do things you could never do before, and you don't want to compromise. If you think hard enough about a problem, you can usually find some way to make it work.

"The scene with the face going through the bars is just like the storyboard. Things used to have to be changed around because maybe the cables were going to show or the camera might not be able to run at a high enough speed during part of the shot. Such mechanical problems often kept us from getting the shot as boarded. When you start eliminating those mechanical problems — which is what we're doing — then you're dealing with it in a two-dimensional flat space and there are a lot fewer restrictions."

Computerized storyboards have made some headway, but Muren is not enthused. "We tried to do them as far back as Battlestar Galactica [a Universal TV series which utilized visual effects on an extravagant scale]. It was an incredible achievement at the time, but they were dull; there were no speed lines and it was hard to change them. Everybody thought it would get better and faster, but it just hasn't happened, and it's been about 15 years. It's easier to find a good artist who knows how to distill a thought into a picture and then make it so that anybody can pick up a storyboard and figure what they're looking at, in motion. We have incredibly detailed storyboards on T2, and by the time we got into it and shot ourplates we had to re-board the whole show, sometimes with three to five panels per shot, so the animators could see the poses to go into."

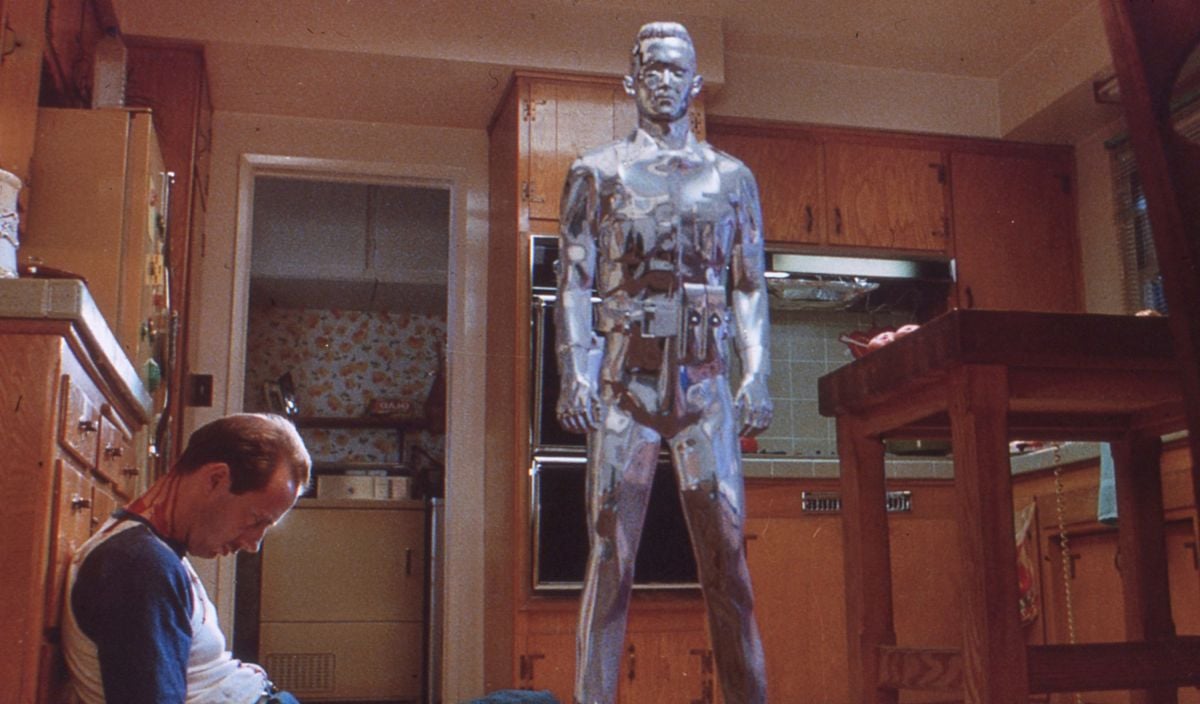

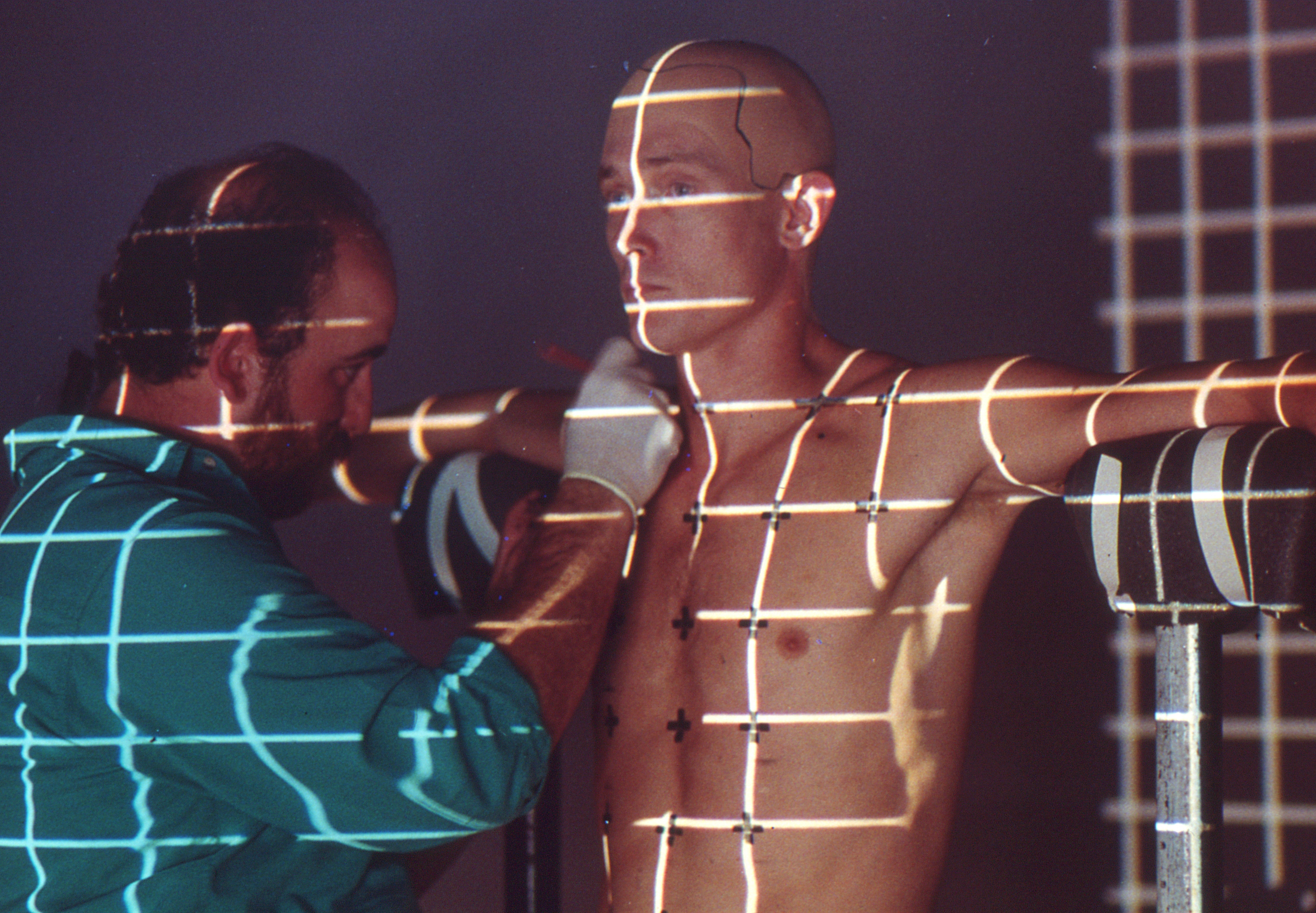

While discussing the film, Muren pauses occasionally to emphasize the need to revise some previous ideas about visual effects when dealing with the CG technique. "It's hard to explain, but it's a different way of thinking<” he says. “You have to realize that we can't yet do a real person with skin, but we can make a chrome figure. Therefore, if there's a chrome guy running around it's a CG character, and if it's a actor like Robert Patrick pushing his head through the bars, it has to be Robert Patrick. They made a chrome suit for him, but it never did work very well and it's hard to believe it in the film.

"When you're setting up models you tend to think in terms of depth. I'm thinking more now in terms of flat. The shooting of the film is merely a step, it's not the entire picture. One of the most important things now is a flat version of what you're trying to do, which is what happens when you digitize it. Once you've digitized it you can do so many things with it, from pushing images around and making geometry, to re-lighting that image, to painting out artifacts that may show up. When you start thinking of these things as flat images that you're going to twist around, you don't have to change things very much for technique anymore, because in shots like that you've created a whole new technique."

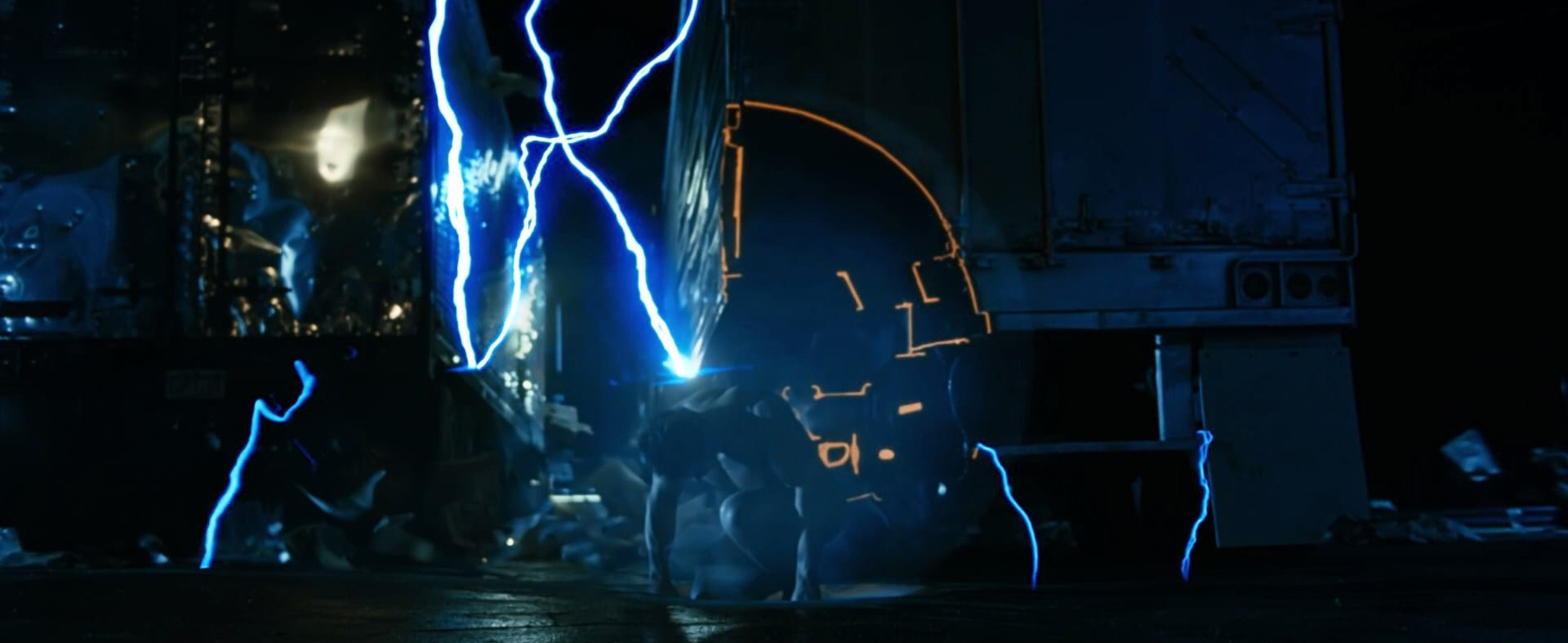

A prime example of new technique via new thinking is the spellbinding scene in which Patrick walks through prison bars. "We shot the original photography of Robert without the bars, but then we squashed and stretched and twisted the film around in the computer to look like bars were pushing and deforming the skin. Then we went in once again in the computer and re-lighted the deformations, because where his skin was pushed in there should be a shadow. So we had to add the shadows on the skin and change the highlights, which can all be done in the computer. We made the geometry in the computer to push the image around.

"In that case we're not making the decision by hand, we're making it by geometry," Muren states. "Geometry decides where the bar is. We're also making the geometry of his head, mapping the footage onto that geometry and then we're pushing it through the bars and it actually deforms. Then, in the composite, the real bars are put back in over it. Everything on the screen in that shot is film — we didn't create anything as we created the chrome guy in other shots. As much as we could we twisted real film, because real film is so rich, and only when we had to did we make anything in the computer."

Years of making hundreds of bluescreen shots did not endear that widely used technique to Muren. "Our original thinking on that scene was to do him bluescreen. That way, we could do all of our geometry altering on it and put it in the background, because then we aren't dealing with the possibility of distorting the background. It sounds feasible, but the result isn't as good. If you shoot bluescreen, the actor is not in the same mood, and lighting never quite matches — there's a little optical difference in it. Bluescreen on a closeup is a disaster. We could have just said, 'We've doing a blue screen,' but we said 'No, let's try to figure some way to solve this, and go for the best image we can possibly get.' We ended up only doing one bluescreen shot. It's in the kitchen when the spike hand comes down into the scene and strikes the woman down. The hand was [shot against] bluescreen. Otherwise, we managed to always find a way to shoot the actor in the set and pull him out or whatever was necessary without bluescreening him in.

The ILM crew shot their own plates in VistaVision on Eastman 5296 high-speed stock. This became a bone of contention because unexpected difficulties were encountered in digitizing the film. Considerable experimentation was necessary before the problem was assessed and remedied. "We found that 96 barely works for input scanning," reports Muren. "It has something to do with the size of the grain. It isn't the same as on film, because the input scanners have a tendency sometimes to make the grain enormously bigger. I think the problem will solve itself soon, as the input scanners get better, but we weren't sure we would be able to get 96 to work. That's a really good stock and in the photo-chemical world it works very well, but it digitizes differently than what you'd expect."

Another point the effects director made very clear is that while the computer is a creative tool, it is not in itself creative. As he put it, "There's no magic to the computers. The computer doesn't know what to do, it's the guys doing the shots who know. They're artists who recognize these problems and know that they have to change the highlights and change the shadows. There are about 35 of them on the show and they come mainly from scientific backgrounds. They have come to know the quality we expect. There's a tendency to do things better than they need to be, because they don't quite know when it's good enough and also because the supervisors and directors are always pushing for more."

A lot of new language has been introduced into the visual effects vocabulary during the past few years. Two processes that haven't yet made the published glossaries of effects terms have been dubbed morfing and make sticky.

"Morfing," Muren explains, "means a metamorphosis on film. Doug Smythe, who works here, wrote that software four years ago and came up with that name. Now it's caught on, everybody's using it — morfing is the hot thing at the moment. We spell it m-o-r-f, a funkier way of spelling it, but everybody else has corrected it to m-o-r-p-h.

"This stuff started out in Willow, and we did a lot of it in T2 where we changed figures around. This is almost a 3-D form of morfing, where we're not just pushing pictures around on sheets of rubber — we push it forward, change it around, re-light it. As with regular effects, there's not just one technique in a shot, it may have three or four different techniques. For the guy going through the bars, there's image processing in there because we're mapping him over a 3-D shape; we have 3-D geometry in there because we're deforming, we're doing a little CG in there in which we're re-lighting — changing highlights and shadows — and there are also some places where the 3-D geometry of the head didn't quite line up with the projection of the head, so there are little artifacts which we would go into and morf over a little or paint out.

"I'm really comfortable with mixing tools, whereas some computer folks are real purists who want the computer and program to do the work, so they can push a button and walk away from it. That doesn't matter to me; if it works, great! But you don't want to spend four years writing the program for one shot, either."

"Make sticky" is utilized most strikingly in a scene wherein a guard walks through a scene and the face of the T-1000 suddenly rises from a checkerboard tile floor. Tom Williams, an animation supervisor, wrote the software for this scene, which became the first "make sticky" test. It's a method of reshaping a 2-D image via 3-D geometry.

Describing the scene, Muren says, "First you see the feet go through. The background is a real plate with a tilt-down of the guy walking through and a lock off. And then we're pushing our 3- D geometry of the head up through it and stretching the pixels of the head where we need to because that data has been pushed. All the grain and everything is stretching, but you don't see it. It's sort of equivalent to setting up a sheet of rubber and projecting a plate on there; you have a mannequin behind it, and you push that up through, but it doesn't have the defects of the mannequin because you've mapped it on and it sticks to the shape and you can animate it. The color is perfect, everything is perfect all the way through, and if you get some little defect you can go in and paint it out.

"That was the first shot that proved this technique we call 'make sticky.' One of the things we thought about was to have a computer graphic floor, blue screen-in the feet walking through, and then distort the CG floor in the shape of a head. When we were on the set at Northridge, getting ready to shoot the plate, Jim said, 'I really need to do a tilt-down on this, so I can see the boots off in the distance, hold it in the frame longer, and I can do a lock-off. Is there any way?' I told him we'd shoot the plate both ways, so it's a lock-off and it's a reference if we do the CG floor and for the lighting of the boots. I was really thinking that we should really try to get this 'make sticky' thing working and that shot proved it. This is a distorted image processing with 3-D geometry. It's something like texture mapping, but it's more specific and specialized. It's going to become a standard and you're going to see it in all sorts of effects pictures."

Utilized in the same scene is a new refining technique known as Ray Samp. This made it possible for the face to seem a part of the surface of the floor as it emerged, rather than merely a separate object suddenly thrusting up. "I would never have thought about something like that scene if I hadn't taken that year off," Muren laughs.

In one memorable sequence, the T-1000 has been frozen and shattered into fragments. Heat from a vat of molten steel melts the pieces into liquid puddles which flow together and are transformed into the living humanoid. The first part of the sequence was brilliantly done by Bob and Dennis Skotak of 4-Ward Productions. ILM then completed the sequence via CG. Muren said, "It's modeled and keyframed to the various poses, front-back, right-left, top and bottom. Then those are made into a cube in the computer. Then the rendering is done — rendering is when you put the surface characteristics into a scene.

“You already have a wire frame but now you’re going to make it solid. Is it going to look like glass, is it going to look like a person, is it going to have hair, or is it going to be chrome? Our renderer, which was developed here, is called Renderman.

“Renderman allows you to make a cube of still photos and you can specify reflectivity within that cube. When you look at it you're seeing the reflections around you. Most of the time we print still photographs, but in that sequence we actually shot running footage for reflections of sparks falling down from the steel mill. When people see that thing rising up through the floor, the background has sparks falling and steel pouring, but sparks are also falling in the reflections. It ties the two together, as though you're surrounded in this really hot world. I try to 'plus' a shot — the director asks for something and he gets back even more than he saw in it. If I can please him, then I know it's going to please the audience. It's hard when you're doing a show like this that's breaking new ground, because you don't know what's going to work and what isn't."

One of the first rules in visual effects is to keep the effects on the screen long enough to register in the viewer's mind, but not so long as to allow him to deduce that it is an effect instead of reality. The new methods solve this problem, Muren believes. "In a six-second shot of the T-1000 pushing through the bars, there is no effect for the first three seconds. He walks up to it, he pauses, then he goes on through. If that had been done as a bluescreen we would have had six seconds of an artifact, so the whole thing would look a little funny. This way, we don't even need to use our tools until it starts distorting, so we have a perfectly normal lead-in shot, because all we've done is digitize it and throw it back out again, and then it's distorted for only those last three seconds.

In the scene of the head closing up, there are three seconds of the head closing and three seconds of the guy walking out of the frame. If we had used bluescreen there would have been six seconds to look at and sense a defect of some sort — there might have been a little matte line at the end when he goes out of the shot or the lighting wouldn't have quite matched. But because there was only a three-second effects shot, the whole second half of the shot is real. There is no clue that it's being faked because the starts and stops of the shots are perfect.

"The shot of Linda Hamilton in the steel mill when she turns around and morfs into Robert Patrick is a good example. When they've done morfing before, most of the commercial houses have used bluescreen because they have to isolate the subject from the background. We chose to do it on the set, so we have a complete lead-in to the shot with no artifacts, we have the change, and the end of the shot with no artifacts. There are only 30 or 40 frames in there to deal with as an effect. It makes it harder, but it makes it better.

"Traditional special effects were incredibly labor intensive," Muren concluded. "It's so much easier to do this stuff now. But if it's easier, everyone's going to be doing it, and then the public will get used to it and be bored by it, so we'll have to come up with a way to use it so that the images are fresh and new!"

For more on the production, check our Terminator 2: Judgment Day — He Said He Would Be Back article from July of 1991.