The Darker Side of Mark Irwin, ASC, CSC

The cinematographer reflects on his career-building collaboration with David Cronenberg and the creation of some of cinema’s most fantastic (and shocking) images.

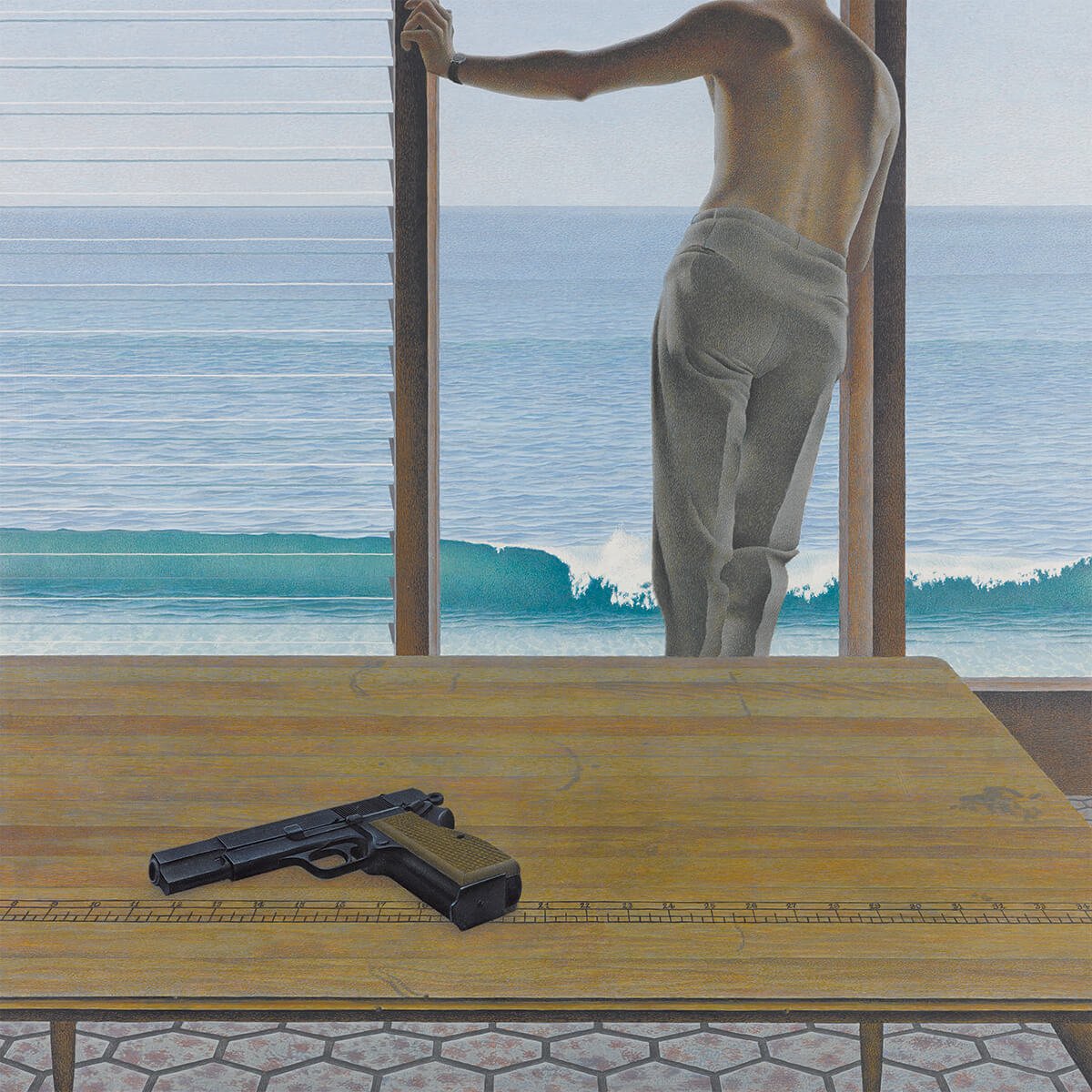

One of Mark Irwin, ASC, CSC’s favorite paintings is Pacific, a 1967 work by English Canadian realist painter Alex Colville. In this daytime scene, the eye is first drawn to a shirtless man silhouetted in a window frame, looking out at a clear sky and flat stretch of blue ocean. The man's leaning posture and a single breaking wave guide the eye downward to the top of a wood sewing table, empty except for an automatic pistol. Colville’s austere, geometric composition possesses a sharp, graphic quality, almost like it was sculpted in paint. The gun, a symbol of violence, feels out of place in the otherwise relaxed environment.

“Every time I look through the camera lens, I hear him in the back of my mind, saying ‘frame it like this,’” says Irwin, whose own images bear Colville’s influence sculpted in light. As a director of photography, his CV boasts more than 100 screen credits — personal favorites include Bat*21, a war film; Youngblood, a hockey film; and Showdown in Little Tokyo, an action film — and four CSC Awards for cinematography.

Inspired by the genre-defying work of French Canadian filmmakers Michel Brault and Jean-Claude Labrecque, Irwin enrolled in the graduate film studies program at York University in Toronto. Upon graduation, Irwin shot and directed 35mm documentary films for TVOntario and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation before moving into low-budget independent features including Point of No Return (1976) and Starship Invasions (1977).

“I was shooting anything I could get my hands on and trying to meet different filmmakers,” he remembers. “The people I’d gone to film school with were also scrambling, so we would employ and support each other. That’s where I learned not just the art of making movies, but the economy of it too. You don’t just have to make the movie, you have to make the day.”

Here are Irwin’s thoughts on pivotal projects done during this part of his career:

Fast Company (1979)

Irwin’s camerawork caught the eye of Peter O’Brian, an English-Canadian producer trying to bring Hollywood-style filmmaking to the then-practically nonexistent Canadian film industry. He'd just finished making Blood & Guts (1978), a wrestling pic shot by Irwin. For his next project — Fast Company, a film about drag racers in Montana — he hired an up-and-coming filmmaker named David Cronenberg to direct.

“I was hired at the last minute,” Irwin relates. “On the Thursday before the first week of shooting, their Parisian French cinematographer left to shoot a film in Paris. I got a call Thursday night to be on a plane by Friday, so I could start the film on Monday. A year ago I came in third for this job.”

Irwin was already familiar with Cronenberg’s previous films, having written his graduate thesis on such early works as Transfer (1966), From the Drain (1967), Stereo (1969), and Crimes of the Future (1970). The director now had a handful of French Canadian TV credits and two features — Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977) — under his belt.

“Fast Company was a completely different world from David’s. Very American. Cowboy hats. Red, white, and blue. Big Sky Country,” remarks Irwin. “We were shooting Alberta for Montana, which was 150 miles away, so it wasn’t like going to Prague and pretending it's New York.”

Irwin and Cronenberg saw Fast Company as a Hollywood movie and that they were playing the roles of Hollywood filmmakers: “We approached it in the same way, academically-speaking: How do we best tell the story? After a week of shooting we found our rhythm.”

The Brood (1979)

Irwin was in Italy shooting a CBC series called The Newcomers when he received word that The Brood was starting in just a couple of weeks. Reading Cronenberg’s script, Irwin saw that the story of a father (Art Hindle) trying to rescue his daughters from his wife (Samantha Eggar) — who is not only involved with a cult but has become the subject of a strange scientific medical process — would be a much different film than their last. “Fast Company is a big outdoor movie and The Brood is very much an indoor movie. It goes inside the characters, into their minds,” he elaborates.

Starting out, The Brood has photographically a lot in common with Fast Company: crisp, clean photography, and naturalistic, low-contrast lighting. But as the dark truth behind the cult and its medical experiments are revealed, shadows begin to creep into each successive scene, until night falls on the dramatic climax.

“This is where my philosophy was born, my first legitimate psychodrama where things go bump in the night, as opposed to crash in the night,” Irwin prefaces. “I want to take the audience on a journey. If you start them off in darkness, they’ll get lost. I show them where they are with scenes that are more or less fully lit, then slowly introduce more and more darkness.”

Scanners (1981)

“All of David’s films are anchored in reality, so we have to film them that way,” says Irwin, even the ones about powerful telepathic and telekinetic humans called “scanners.” It doesn’t take long for the film to go dark when, in one of its early scenes, a rogue scanner (Michael Ironside) uses his powers to explode the head of another telepath (Louis Del Grande). It’s an infamous moment in cinema, sudden and all the more shocking for its graphic realism.

Editor’s note: The scene is largely played out in the trailer above, and includes the explosive, NSFW finale.

To hear Irwin tell it: “We shot the scene in the lecture hall of a community college in suburban Montreal, then took the stage backdrop down to a warehouse by the Montreal waterfront. All the trucks were parked at the edge of the set, which was five cameras — including a Mitchell Mark II running at top speed of 36 fps — a background flat, and this Louis puppet at a table.”

Special effects legend Dick Smith consulted on the film’s molding, casting and prosthetic makeup, but it was left to fledgling special effects artists Chris Walas and Stephan Dupuis to execute the ideas. “The head was completely realistic,” Irwin continues. “Inside was all the brains: vermicelli, burger, latex scraps and gelatin — all bloody and gray. But the explosive squib inside the head gave off a giant spark. That wasn’t going to work for David. These are thoughts, not ballistics that make people’s brains blow up. It had to be organic. Another squib, another giant spark.

“Gary Zeller was our New York special effects guy. He wore combat gear all the time, has this giant scar across his face; an ex-military guy. He got fed up. He told everyone to turn on their cameras and then get into the trucks. Gary got down on the floor behind the Louis puppet with a shotgun loaded with salt, and blew the head open.

“When we saw it at dailies the next day, everybody cheered,” Irwin fondly recalls. “But Pierre David, one of our producers, jumped up and waved his arms in front of the screen. ‘No, no! We must re-shoot! We will get an ‘X!’’”

Nobody wanted to do it, but they made three more heads and a week later, Irwin and the crew were back in the warehouse: “Take one with the shotgun: Confetti. Stephan apologizes, ‘Oh, we don’t know what happened!’ Take two: Mint jelly; just a geyser of green. ‘We don’t know what happened there, either!’ The last head was made of solid plaster, like its brain had calcified. They basically sabotaged the shoot, and the take that’s in movie — the one that didn’t get an ‘X’ — is the one we did the first time.”

Videodrome (1983)

Irwin describes Videodrome, his fourth collaboration with Cronenberg, “a slice of reality in Toronto. Instead of Civic TV [in the movie], we had Citytv. [Station owner] Max Renn (James Woods) shares a lot of dynamic qualities with the station’s real-life founder. So David looks at reality and asks ‘What would we find if we turned down a dark alley?’ Snuff videos, of course.”

Videodrome is a full-on leap into the realm of the phantasmagoric that was only hinted at in Cronenberg’s previous films. “The challenge for David and me was to make something completely phony look totally real,” says the cinematographer, who opted for a straightforward approach to shooting some of the film’s most fantastical moments. “You can telegraph a lot by framing and camera moves, then people are braced and ready for it, but getting mugged in broad daylight is a lot more shocking than getting mugged at night on a dark street.”

Makeup effects artist Rick Baker created a number of transformation effects for the film, some of which depict Renn’s surreal physical evolution as the Videodrome signal hidden within the channel’s disturbing-yet-addictive programming re-wires his brain.

Shooting the scene in which Renn’s hand becomes trapped in a slit in his stomach was “a photographic marathon,” says Irwin. Wood’s right arm and hand were hidden behind his body and tucked into his belt, and a prosthetic arm was strapped to his shoulder.

“What I found with prosthetic effects in a ‘real’ situation like Videodrome is that latex and human skin don’t reflect light in the same way,” Irwin elaborates. “But we discovered that if we used a light mineral oil and water mixture on the skin as well as the prosthetic, that the sheen would produce a reflection on the latex.”

Adding an additional layer of realism, the violent and pornographic Videodrome content appearing on Civic TV, along with the television monologues of Professor Brian O'Blivion (Jack Creley), was shot by Irwin on 2" videotape with an Hitachi SK-91 broadcast camera. For monitor inserts, Irwin filmed the playback off a CRT monitor with a 50mm prime and a Panaflex X. “Even with a 144-degree shutter, shooting a 60Hz color signal at 29.97 frames produces a thin narrow line that slowly travels up the image,” says Irwin. “David didn’t mind that. It gave him the rough edge he was looking for.”

The Dead Zone (1983)

“David doesn’t come to set with a preconceived notion of anything other than what’s in the script. No shot list, no storyboards. He wants the blocking to tell him where to put the camera,” says Irwin. “When it came to The Dead Zone, we took an austere approach.”

Based on the Stephen King novel, The Dead Zone is a small-town-boy-makes-good story, until the boy, Johnny Smith (Christopher Walken), is in a horrific car accident that leaves him in a years-long coma. Recovering, he is physically weakened, but also left with a powerful psychic ability.

“Out of all of the films I made with David, The Dead Zone is the only one where I had a mission statement,” Irwin muses. “We were scouting in places like Niagra-on-the-Lake and Vermont, and he told me to ‘make it look like Norman Rockwell shot it.’ I realized then that this was a film about things that go bump in the day.”

When Smith touches or takes the hand of another character, he sees into the secret parts of their lives. “Christopher was adamant about reacting to these touches with a strong jolt, and it needed to be an external stimulus,” says Irwin. “We ended up using a handgun loaded with blanks. Everyone wore headphones and goggles. We’d shoot the gun off right next to the camera, and he would react.”

The Dead Zone was also one of the few times Irwin convinced Cronenberg to indulge in creating a classic jump scare, in the scene where Smith suddenly encounters Sheriff Bannerman (Tom Skerritt) in a hallway while searching the home of Bannerman’s deputy. “I noticed the mood of the scene and I said to David, ‘This is where someone jumps into the foreground.’ It was a gag I’d picked up from doing horror films between David’s projects. We did one take with Chris and Tom and that’s the one in the movie. Sometimes the audience needs a jolt, but you can only do it if you set the proper mood.”

The Fly (1986)

“There’s no journey into darkness when you start in darkness; the lighting style should be in constant transition,” says Irwin of his work on The Fly, Cronenberg's retelling of the 1958 horror classic (AC Archive subscribers can access our September 1986 print coverage here). “It’s like a frog in a pot of boiling water. Ease the audience into a story and an hour later they realize, holy shit, this is scary.”

Jeff Goldblum plays scientist Seth Brundle, whose DNA is crossed with a common housefly in a teleportation experiment gone awry. Geena Davis plays tech journalist Veronica Quaife, whose professional interest in Brundle’s research leads to a personal involvement. The two meet at a corporate press event in a bright, spacious ballroom. They retire to Brundle’s loft, the mostly well-ordered abode of a mostly well-ordered person, for a private demonstration of his teleportation pods. From then on, the two characters spend a lot of screen time together, which became a challenge to film as Brundle’s transformation from man to insect progressed.

In later scenes, when Brundle's appearance becomes more twisted and monstrous — and his apartment starts to look more like a dungeon — Irwin uses darker, moodier, and more specific lighting with rims and shadows. “Geena has very white luminous skin, so she had to be one and half to two stops darker,” says Irwin. “Jeff had to be lit two to three stops brighter when he was in full makeup."

Brundle cowers in the darkness like a tragic hunchback, his eyes twitching pinpoints of light in deep, leathery sockets, while Quaife’s bluish moonlight key fully illuminates her horror-stricken face. “I was both lighting and withholding light to create a mood,” says Irwin. “The pictures tell the story and the story is furthered by the mood created by those pictures.”

After The Fly, Irwin and Cronenberg’s careers took different paths. The cinematographer would go on to distinguish himself with such films as Youngblood (1986) and Chuck Russell's remake of The Blob (1988), as well as high-profile Hollywood genre projects including RoboCop 2 (1990), Passenger 57 (1992), and Scream (1996), before teaming up with directors Bobby and Peter Farrelly for a series of comedy blockbusters.

“What I learned from David I would bring to other films and what I would learn from other films I’d bring to David,” Irwin reflects. “I’d like to think I taught him as much as he taught me.”