The Handmaid’s Tale: Rules of Engagement

Cinematographer Colin Watkinson and director Reed Morano, ASC discuss their series adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s “speculative fiction” story.

Cinematographer Colin Watkinson and director Reed Morano, ASC discuss their series adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s “speculative fiction” story.

Unit photography by George Kraychyk, courtesy of Take Five and Hulu.

Developed by showrunner Bruce Miller from Margaret Atwood’s novel of the same name, Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale is set in the post-American religious fundamentalist state of Gilead. The story follows Offred (Elisabeth Moss), one of a group of handmaids who are forced into lives of subservience and tasked with bearing children for the barren wives of their totalitarian masters.

Offred, though, remembers a time before Gilead — when she was known by her birth name of June — and she longs to be reunited with her own daughter, who was abducted by the state. Meanwhile, an underground resistance builds among the handmaids and the servant class known as “Marthas,” and Offred finds herself recruited into their cause.

Colin Watkinson was behind the camera for all 10 episodes of the series’ first season. ASC member Reed Morano served as an executive producer for the series and directed the first three episodes. Additional directors included Mike Barker, Floria Sigismondi and Kari Skogland.

Watkinson and Morano welcomed AC to the set in Toronto, and each spoke with the magazine for separate interviews after the production wrapped. Those conversations have been combined for the following Q&A.

American Cinematographer: What was it that attracted you to this story?

Colin Watkinson: It had been years since I’d read The Handmaid’s Tale, back in the 1980s before the first film came out, and it’s one of those books that sticks with you. Reed came after me because she was a big fan of The Fall [see AC May 2008] — and I’d been following her career since seeing Frozen River [AC Aug. ’08]. Immediately after seeing that film, I had to go and look up who was operating that camera.

Reed Morano, ASC: After I saw The Fall, I tried to find Colin so I could tell him how much I loved it, and when it came time to find a cinematographer for The Handmaid’s Tale, he was one of the first people who popped into my head. Thankfully, he was available!

What were your initial creative conversations about?

Watkinson: I started by pulling reference pictures — including the work of Oleg Oprisco and Vermeer that I thought could exemplify our palette — and Reed also had a look-book. When I arrived in Toronto they’d started putting [imagery] up on walls, and the pictures I’d sent her were already up.

What can you tell us about the palette?

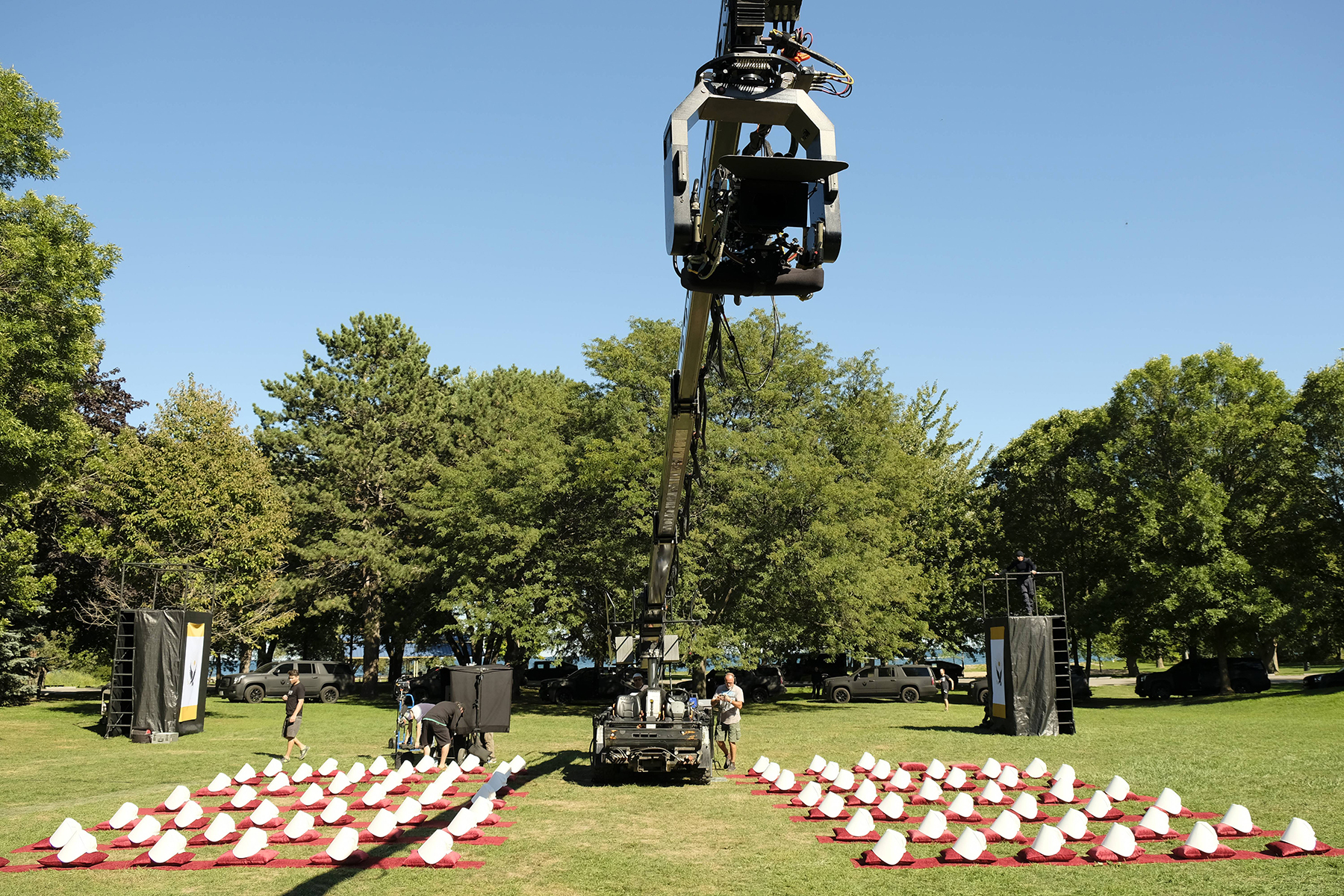

Morano: The way that Margaret writes is very atmospheric. She created this vivid world, with a society based on color segregation, which provided a visual direction. The Handmaids wear red, the Commanders’ barren wives wear blue, and the Marthas wear gray — [the Marthas are] the help; they’re barren and can’t take on a partner. We used a particular shade of red that’s complementary to a peacock-blue, and red and blue are the most prominent colors in Technicolor, which was part of my inspiration for those shades. I thought if they were in a frame together with a neutral background, it would be so striking.

Watkinson: Our production designer, Julie Berghoff, created her sets with that in mind. Some things changed along the way: Offred’s bedroom in the Commander’s home was originally going to be white, and it came out to be more of a blue-gray color. Throughout the season, in fact, the color of the light that came in through the window would change dramatically, so the whole room — which was tiny — never felt like it looked [exactly] the same. Offred’s bedroom was built on stage, 5' off the ground due to the staircase at the end of the corridor. Outside the windows we used 10K Molebeams for sunlight and Arri SkyPanels either bounced into frames or pointed directly at the window, depending on the scene. The SkyPanels are fully tuneable from 2,800 Kelvin all the way to 10,000 Kelvin. Occasionally, we used 1⁄4 CTO on the Molebeams to increase the warmth of the sun.

Given that it was a set, what took precedence: realism or expressionism?

Watkinson: We would definitely do things to enhance the story. For example, the scene where Offred and the Commander [Joseph Fiennes] were having ceremonial sex in a bedroom was a specific story point, so we left the lights on. In a bedroom at night that’s not what you would normally do, but I liked it because it felt more uncomfortable.

Did you go back and read the book when you started working on the show?

Watkinson: I pointedly didn’t do that. The script was the bible for what we were shooting, and that’s what had to be followed. The script was so visual, and a lot of Margaret’s prose was already in there — in descriptions and dialogue and voiceover. I had enough influences as it was; I didn’t need any more. I didn’t re-watch the 1990 film [directed by Volker Schlöndorff and shot by Igor Luther], either.

The audience will invariably compare your work to the source material. Was that ever a factor in the decisions you made?

Watkinson: It was, but Margaret was a producer on the show and she was happy with the script’s translation. If Margaret loved the script and so did everyone else, that was enough for me.

What was your collaboration with Reed like?

Watkinson: I knew what her strengths were and she knew mine, but it was still a bit unnerving at first because our work is so different. Reed’s visually dark — definitely much darker than me. The two of us were exploring how we were going to meld what we liked and then tie it into the story. Before we started shooting I think I said to her, ‘I don’t really know what I’m doing here,’ but she truly believed that our different styles would splice together seamlessly.

Morano: If people look at what Colin had done before The Handmaid’s Tale and what I’ve done in my career, they probably wouldn’t put us in the same category at all. But I thought we could take the spectacle associated with Colin’s work and the emotional aspect associated with my work, and join forces to create something that is visually striking and emotionally moving, and it would be a whole new style for both of us.

How did you define your approach to the show’s flashbacks?

Watkinson: We had two levels of flashbacks — pre-Gilead and early Gilead — and we really didn’t want to go through any special processes or gimmicks to express them. So we came up with three different camera styles so you always know what time period you’re in. Reed wanted modern-day Gilead to be Kubrick-esque in its composition, which I did a lot of when I worked with Tarsem — The Fall is very formal compositionally. The pre-Gilead flashback is very Reed: a handheld cinema-vérité look. The middle-ground early Gilead melds the two, with a slightly more desaturated look. We would break the rules where it was appropriate for the story. I mean, rules are made to be broken. It was fascinating to watch the other directors use and break the rules.

Can you share an example?

Watkinson: We said we wouldn’t do [over-the-shoulder shots], but there’s a scene in the fourth episode, directed by Mike Barker, where Offred and the Commander are playing Scrabble, and she asks him what happened to the previous Offred. Mike decided that in this moment, where there’s this intimate connection being made, the cameras should slowly move into overs. He did that again with a pre-Gilead flashback — when June is with her husband, Luke [O-T Fagbenle], in a restaurant — but in a handheld way, so one was very formal and the other was very loose, but with the same idea.

Why no over-the-shoulders?

Morano: Everybody in this new world of Gilead is so isolated. Everyone is segregated, and you can’t trust anyone or be yourself in front of anyone. We wanted to convey that visually, so when we’re in Gilead you have these formal, symmetrical compositions with characters isolated in the frame, and when we go into flashbacks it’s this romantic, vérité, handheld style, where the characters share the frame with each other more often. The freedom of our society is in its diversity. We can wear what we want, say what we want, listen to what we want. But in Gilead there’s no freedom. So the camera in the [story’s] past — in what is our present day — is messy and free-flowing and wild and romantic, and the camera in Gilead is rigid and clinical and stark and graphic and symmetrical.

Watkinson: Also, we saved going in for close-ups. When we did shoot a close-up, we wanted it to be a powerful expression. You’re really [telling the audience] what to look at. If you use close-ups all the time — well, do anything too much and it becomes ordinary.

How did the show’s other directors respond to these rules? Were they expected to adhere to the vocabulary that you and Reed had established?

Watkinson: No one ever [explicitly] told them to, but they didn’t want to change the style, either. It would come down to the director and what they were comfortable with in their own visual vocabulary; it was about taking what they brought to the table and intertwining it with our language. You try to be rigid, but you also don’t want to stifle people, because then a lock-up happens and you end up shooting nothing. So it was an evolving style. Each director was unique, but it was all under the same umbrella.

Did the other directors turn to you for guidance?

Watkinson: In visual terms, yes, but I try to stay behind the directors. They should lead the way.

What can you tell us about your collaborations with Julie Berghoff and costume designer Ane Crabtree?

Watkinson: Julie loves to use color and texture and depth, which is great for me. She’s bold, and involved, and she does things that are totally out of the box. And Ane would pound us with information. Videos, look books — we always had something to work with, and we would see all the iterations of her work. It was a fully inclusive collaboration.

Aside from the stages in Toronto, where did you shoot?

Watkinson: We shot in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for a lot of the exteriors, and the Commander’s house was in Hamilton, outside of Toronto. The one word that I think keeps being misused is ‘dystopian.’ [The Handmaid’s Tale is] more of a speculative vision, what possibly could happen. Even though it’s absolutely ridiculous and alien, it speaks to the audience because of our present political climate. The situation feels real, so the world needs to feel real. The hardest location to find was the ‘Loaves and Fishes’ grocery store. It had to feel like a supermarket that you’ve been to before, but transported into this world of Gilead. Reed didn’t want it to look like a Whole Foods or anything specific. The audience has to be able to project their own experience onto it.

Did Hulu have a mandate to shoot on a specific camera or at a particular resolution?

Watkinson: We showed them the specs for the [Arri] Alexa Mini, and they accepted it. Also, we wanted to shoot the 2.0:1 aspect ratio, and Hulu accepted that as well. They were totally open to anything that would make the show stand out. We captured on CF cards and recorded at 4K UHD ProRes.

What lenses did you use?

Watkinson: Initially, Reed wanted to use Panavision PVintage Prime lenses but there weren’t a whole lot of them available to us, so I showed her the Canon K-35s. She would constantly push us to go wider on the aperture; the image would start to break up a little bit, but the falloff was amazing. The challenge with the Canons is that you’ve basically got an 18mm, 24mm, 35mm, 55mm and an 85mm. My two favorite [focal lengths] — the 27mm and 40mm — aren’t in there, so we also had 40mm and 28mm T2.1 Zeiss Standard Speeds. We really wanted to stay with the aesthetic of the Canons, and that was as close as we could get.

Did you shoot wide open all the time? Some of the formal compositions look like they have more depth of field.

Watkinson: It might have the appearance of being a deeper stop because it’s a wider lens, but we always wanted a bit of falloff. We rarely went above T21⁄2; going above T2.8 was very unusual. Once I realized our focus pullers could deal with it, we would even push our stop to T1.5. The 24mm Canon had really interesting characteristics at that setting — sometimes it was great, and sometimes it ruined the shot. It was amazing to watch how our A-camera first, Gottfried Pflugbeil — who’s been a focus puller for 20 years — would just caress things into focus; it never snapped. I was a focus puller myself and I really loved doing it, but I never did anything close to a wide-open 50mm Steadicam shot, or a wide-open 35mm handheld close-up. There’s no forgiveness. Either it’s in or it’s out [of focus].

Did you use a lot of marks, or was it kind of a freeform approach?

Watkinson: Sometimes we used marks, but Gottfried had his own laser-focus system that went on top of the camera, which is way more accurate than anything else I’ve seen out there. He cranks up the sharpness on his monitor and has his Preston [wireless lens controller]. He also sits at a certain angle to the camera [which was operated by Michael Heathcote], so he can judge the distance with his eyes. He’s combining the old school and new school.

Did you use any cameras other than Arri’s Alexa Mini?

Watkinson: We had some specialty shots [for which] we used the Sony a7S with a PL mount, and used the K-35 Canons on it.

When I visited the set, you mentioned that your collaboration with digital-imaging technician Ben Whaley was very influential to the look of the show.

Watkinson: Reed and I approached him about the look we wanted, and he created a style on the set. We graded the show live on a per-shot basis, and the LUT boxes we used allowed remote control of camera settings and internal NDs, so the building of looks was in-depth and organic. We used CDLs so that they were trackable through editorial, visual effects, and into the finishing room. In fact, the finished product is very close to what we were all seeing on set.

You also mentioned that you started the color-grading process on set.

Watkinson: We had an edict from production to create on-set dailies. Ben realized this for us and the results were excellent.

What happened to your footage at the end of each shooting day?

Watkinson: Deluxe Toronto laid grain onto everything. We didn’t want to put it on at the very end, after we’d gone through the whole production without it. That was just a layover that they would add while they were syncing the sounds. In post, we have adjusted the grain to suit the color and ambience of each scene. Deluxe provided a selection of 10 grain types and we chose the one that we thought added the right amount of texture.

What kind of adjustments have you made in the final color grade?

Watkinson: Since we started grading while we were shooting, I pulled in Ben and kept him working on [the color grading] as soon as we wrapped. We’re supporting the work we did on set. We’re working with [Deluxe Toronto senior colorist] Bill Ferwerda. He visited the set and sat with Ben to get an idea of what we were doing. I would say we were at least 70 percent of the way there before we even started our final color. [Editor’s note: Ferwerda graded The Handmaid’s Tale using Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve.]

How many deliverable versions of The Handmaid’s Tale will there be?

Watkinson: There’s the 4K HDR, the HD version and the international version.

How has your experience working with Hulu differed from working with more traditional networks or studios?

Watkinson: Hulu is very collaborative, and there’s nothing being done without anyone knowing, particularly for me with the look. What we’re doing here in television is storytelling first and foremost, and everyone involved was a part of making this happen.

Watkinson was invited to join the ASC in 2018.