The Northman: An Epic of Fate, Fantasy and Brutal Formalism

Cinematographer Jarin Blaschke renders an ancient era brimming with bloodshed and bathed in monochrome moonlight for director Robert Eggers’ most ambitious feature yet.

Unit photography by Aidan Monaghan, courtesy of Focus Features

Jarin Blaschke has spent over a decade making movies with Robert Eggers. But when the time came to begin filming The Northman, neither of them felt prepared for what lay ahead. “Coming from indie films, how could we?” Blaschke asks rhetorically, in between laughter.

The cinematographer first worked with Eggers on two shorts, and then on The Witch — the writer-director’s feature debut, a folk-horror period piece shot in 25 days, predominantly with natural light. Their follow-up, the black-and-white psychological thriller The Lighthouse, “was on the larger side of the indie world,” Blaschke says, but was made for a fraction of The Northman’s roughly $70-90 million budget, and filmed in a remote fishing village in Nova Scotia. Traversing the coasts and castles of Ireland to shoot their new historical epic was a different beast entirely — a production scale as sprawling as the story they were tasked with telling.

The Northman follows Viking prince Amleth (Alexander Skarsgård), whose fatalistic journey, from adolescence to adulthood, is guided by his vow to avenge his slain father, King Aurvandill War-Raven (Ethan Hawke). Its screenplay, from Eggers and the Icelandic poet Sjón, is rooted in the timeless Scandinavian legend that inspired Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Like The Witch and The Lighthouse, its style melds flourishes of dark fantasy with rigorously researched period detail — but unlike those films, Blaschke says it required a more “brutally formalist” approach than he’d ever attempted before.

“The movie is about destiny — about clarity, and things that are meant to be. So, in the blocking and camera movement, we were always trying to distill a scene into its simplest form,” Blaschke explains. “That doesn’t mean we’d find the simplest way to accomplish each shot. But for the viewer, we wanted scenes to move from one moment to the next in a very succinct, meaningful way.”

One such scene serves as the introduction to adult Amleth: At the start of the film’s second chapter, we find that he’s grown to become a Viking berserker, years after fleeing the massacre of his village wrought by his uncle Fjölnir (Claes Bang).

In a wide shot of a raging river in the land of the Rus, trees from a nearby forest enframe the water’s surface, on which a Viking longship glides in and out of view. When another longship sails in from left and into the foreground, the camera tracks toward it, hovers above the berserkers onboard, and pans right into a track toward Amleth, who rows rhythmically with his shipmates en route to a raid. Several beats pass, and Amleth shifts his brooding gaze leftward, prompting a rightward pan to reveal a father and son as they’re shot dead on their fishing boat by another berserker’s bow and arrow.

To move the camera — a Panavision Millennium XL2 — onto the boat, Blaschke, camera operator Chris Previn, and gaffer Seamus Lynch considered using cables. But after consulting with key grip Darren “Dutch” Holland during prep, they opted instead to employ a Scorpio 45' telescopic crane. The crew built a dance floor on the boat’s uneven planks, allowing dolly grip Claudio Del Gobbo to smoothly track across it. Visual effects supervisor Angela Barson also advised him on how best to break up each take, so that they could be rendered invisible and married as one long shot through stitching in post.

Satisfying Eggers’ penchant for long, complex shots took “a lot of holistic planning and dialogue across departments,” Blaschke says, and filming the ensuing raid sequence was no exception. As if covering the berserkers’ onslaught of an entire Slavic village wasn’t ambitious enough, the crew rejected the multiple-camera approach typical of most large-scale battle scenes and dared to capture it all with just one camera.

“There was no figuring this out on the day,” Blaschke laughs. “We had to hammer it all out, baby step by baby step. For me, it became a kind of greedy obsession: to see almost everything in the movie before we shot it.”

“When you have great storyboard artists like Adam Pescott and William Simpson, it’s hard not to fetishize that part of the process,” he continues. “At least 90 percent of The Northman is storyboarded, good enough to be a proper graphic novel of the movie. So, the Slavic village in the raid scene had to fit the boards.”

Production designer Craig Lathrop — another of Eggers’ frequent collaborators — also worked closely with Blaschke, building a scale-model version of the village to help the cinematographer make composition choices that suited the space.

“With the model, we could move buildings around a bit and I’d say, ‘Craig, if this building was a little closer, then after this kill, you would see a guard break down and open the palisade door, and then that charge to the door could lead to this next street,’ and so on. Then, we’d show up on location and the latest village plan would all be taped out in the mud, and we could look through a finder to figure out the line of the camera.

“I had these clear sheets of plastic on which we could draw on-set plans, acting as analog virtual lenses. The art department would draw a big ‘V’ on the sheet, and the acute angle of the V would match the horizontal taking angle of a given lens. So, there’s a wider V for 24mm, and a slightly narrower V for 27mm, and so on. When away from the sets, I could place these on the plans and I could tell what the lens would see, and start designing shots that way.”

Together with stunt coordinator C.C. Smiff, Blaschke ran through his planned camera moves to determine where the carnage of the scene would need to unfold. “It’s basically saying, ‘The camera wants to move from here to here, so we want Alex [Skarsgård] to move to the foreground, back to the background, and then across… what are the actions that can justify this line?’” he notes. “So, the camera’s a bit oppressive. It’s dictating where the stunts can happen.”

Ultimately, the raid sequence ended up with four stitches, and the aftermath of the raid — which Blaschke likes even better — has just three. In this chaotic scene, a wide shot first finds the bloodied berserkers resting after battle, then moves left into a 360-degree pan that displays the horrors inflicted by the invading clan. Surviving women of the village panic, wailing babies are stolen from their mothers, and hordes of conquered peoples are shepherded into a barn, barricaded, and burned alive. Amleth observes this savage cruelty with quiet satisfaction — our reminder that his quest, however mythic, is not necessarily noble.

“I enjoy that scene more than the raid itself because it has more emotional layers and points of view,” Blaschke says. “It plays with perspective: It flows between several brief individual stories until landing on Amleth in an extreme close-up, suddenly revealing that this has all been his observation and point of view. Then he turns, and we leave him again to go toward what he’s looking at. With our blocking, we wanted to link objective and subjective points of view together, and in those longer shots, I tried to take that to its most extreme.”

For Blaschke, The Northman’s moonlit scenes were yet another matter of perspective. While most of the film’s daytime imagery is decidedly desaturated, it seems lush when compared to the cinematographer’s monochromatic vision of nighttime.

“That was a longstanding curiosity of mine: ‘Could we depict moonlight in a movie so it looks closer to the human experience of nighttime?’ If you’ve gone out in the middle of the night in a rural area, you don’t see color, and you can’t see long wavelengths at all. If you saw a red rose in the middle of the night, not only is it monochrome, but your red becomes black, not gray.”

Growing up in central Oregon, Blaschke experienced many starlit nights, so he was familiar with this phenomenon, known as the Purkinje effect. Though his initial experiments to recreate it didn’t quite click, he found success by summoning a key piece of his kit from The Lighthouse — a cyan filter custom-made by Schneider Optics that helped him earn an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography in 2020.

“I put that filter on my camera, and at first, it looked horrible. All you could see through it is green and blue,” he recalls. “But then I thought, ‘What if I desaturate from this base?’ And it looked great! So, I made a new version of the Lighthouse filter — which I could use as a day-for-night filter, too — and called it the ‘scotopic filter.’”

Amleth’s encounter with a strange seeress (Björk) is the first scene in The Northman to showcase the scotopic filter’s effect. Later, during his battle to obtain a magic blade from an undead mound dweller, the action is also steeped in the filter’s silvery sheen, evoking a sense of otherworldliness that befits the film’s fantastical elements.

Other moonlit moments, like when Amleth narrowly evades Fjölnir and his guards while sneaking around his farm, fall into a separate category — what Blaschke calls “mixed light scenes,” with touches of warm light from nearby fires. He conceived of their look, he says, while on a summer trip to Mount Kilimanjaro prior to production: “On my first night there, I was in a camp with a lot of tents and saw moonlight across the side of the mountain. Everything outside looked black-and-white… but when I looked at the tents, people had their flashlights and lanterns turned on, and I saw islands of full color within my black-and-white vision. My eye was giving me a fully saturated image right next to a monochrome image at the same time. I thought, ‘OK, if there is a threshold of luminance in a portion of your vision, your eye will deliver color. How do I achieve that?’”

Blaschke’s tests soon revolved around finding the right gel and the right amount of cyan that would capture this full color spectrum in the same frame. As he remembers, “Three months into prep, while trying to sleep, it suddenly struck me: ‘What if we had a crazy low-pass cyan gel on HMI moonlight, and then I put a mild CC 40 cyan filter on the camera?’ The ‘moonlight’ would pass unaffected, you can’t filter pure cyan light to be any more cyan. But any firelight in frame would become more neutral in color. I could then print the whole negative red, to counteract the cyan filter. The added red in the grade restored firelight to its expected red color, while simultaneously negating the pure cyan moonlight — turning it to monochrome. In the end, it’s pretty good, but not yet perfect. I’ll keep fine tuning the spectral recipe from film to film.”

While The Northman’s filters began from what Blaschke established in The Lighthouse, he found himself in uncharted territory when working with LEDs, which were integral to some of the film’s most spectacular set pieces.

During the film’s first chapter, young Amleth (Oscar Novak) prepares to inherit Aurvandill’s kingdom in a ritualistic blood oath. Aurvandill slices into his own stomach and commands the frightened boy to approach him, bellowing, “In our blood, behold the tree of kings.” When Amleth places his hand inside the wound, the camera pushes into the king’s flesh as it opens, revealing a glowing portal to his ancestral tree, whose tangled branches connect him with his dead and living descendants.

For this sequence and others that scale up the tree, Lynch programmed a “giant rainbow” of LEDs to run through hues of white, baby blue, and pinkish salmon. The color pattern was inspired by the celestial work of Odd Nerdrum,one of Eggers’ favorite painters. Filming with the Arriflex 435 ES, Blaschke shot multiple passes on Novak and the other actors featured in these scenes against a greenscreen using motion-control. “Moving at 120 frames per second, the camera could potentially smash our child actor in the face,” he explains. “We had to start in reverse and run it backward.”

In the film’s feral climax, Amleth meets Fjölnir on Mount Hekla — the Icelandic volcano known in Norse mythology as The Gates of Hel — for a fiery sword fight to the death. Blaschke filmed most of the scene in Northern Ireland’s Hightown Quarry, again relying on LEDs, this time to transform the set into a boiling cauldron. “Any area of the frame in which you see lava is just a big SkyPanel,” he says. The crew placed multiple Arri S360-C SkyPanels in a dug-out area in the quarry, and Lynch programmed the lights to simulate a flow of lava to slowly move down the slopes.

Opting for Kodak Vision3 50D stock, Blaschke sought to convey the scope of the final battle in its texture. “I wanted it to be as smooth as possible, without seeing grain, and as close as it could be to a large-format film,” he says. “With this slow stock, we could shoot into the light source, and at a Kelvin temperature of 2,900 degrees, it was plenty warm for a film balanced for daylight. In the grade, I gave it a little extra bit of red, and it all came together.”

Howling and hurtling toward each other one last time, both men land their finishing blows: In an instant, Amleth’s blade beheads Fjölnir, just as his pierces through his nephew’s heart. Fulfilling his promise to “cut the thread of fate,” Amleth dies in a state of spiritual ecstasy, envisioning his long-awaited ascent to Valhalla. And in The Northman’s exquisite closing shot, he’s carried by a valkyrie on horseback, galloping through stars up toward celestial gates.

“Shooting the VFX plates for that last shot was a new thing for me,” Blaschke says. Whereas the first scene in which the valkyrie appears utilized several greenscreens built into the quarry, the film’s final shot was done without greenscreen, as the crew was surrounded by rock face. "The scene was backlit with hard light at two and a half stops under, and the fill light was four stops under, which was my recipe throughout the movie,” the cinematographercontinues. “But the question was, ‘How do I keep that accurate to within a third of a stop for this long run that the horse makes?’ It took a long time setting that up.”

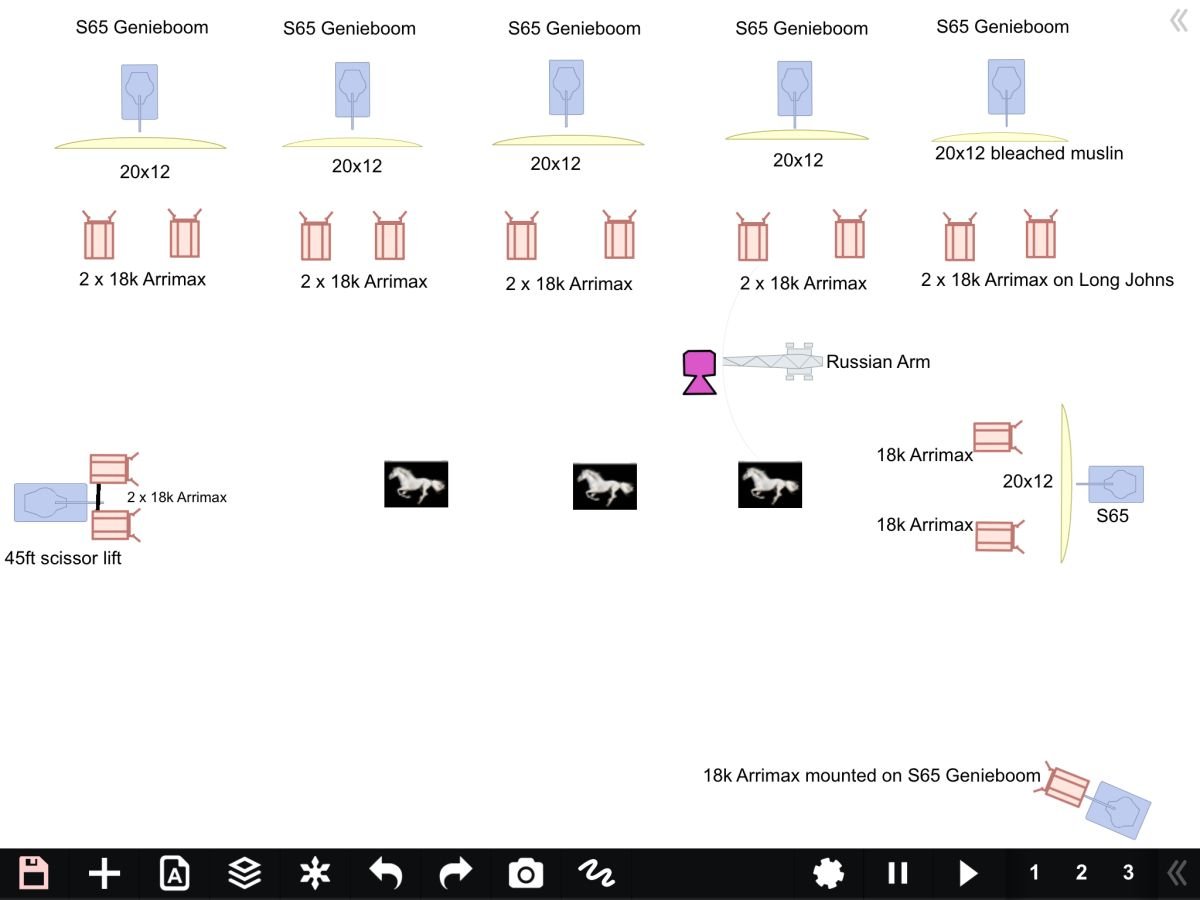

To light a large swath of the space for their horse to ride through, Lynch advised Blaschke to use multiple 18K Arrimax units bounced into a wall of muslin (see diagram below). Rigging gaffer Gareth Heatherington and head of department rigger Hugo Wilkinson positioned six S65 Genie booms with 20'x12' bleached muslin — five of which became the crew’s soft side push, as they bounced the Arrimax units into them. Best boy Ger O’Hagan balanced these machines by using a combination of scrims and spot and flood, to give the crew a consistent four stops under. Two of the Arrimax units were rigged to a 45' scissor lift — which served as the faraway light of Valhalla — and another was mounted on one of the booms, to provide a mobile edge light. “Just another busy night lighting The Northman,” says Lynch.

After making a movie this complex, Blaschke has developed an addiction to these sorts of challenges. “With The Northman, I feel that we created some interesting blocking and a clear style,” he says, “but we’re still too reliant on shot-reverse-shot for when people are sitting around during dialogue scenes. We haven’t cracked that yet!”

However far away from indie world The Northman may have taken them, Blaschke and Eggers remain bound by this experimental spirit. “This film is like a first draft, with a whole bunch of ideas that can definitely be improved,” the cinematographer says. “I ended up with at least one underexposed night exterior, before I truly knew my filter factor for an experimental technique. But it took just that one error to correct my technique. And as far as equipment goes… cranes blow around a lot! It’s things like that that I’ll learn from and continue to hone. But as Rob likes to say,‘We now know how to shoot the movie we just shot.’”

TECHNICAL SPECS (and notes from Jarin Blaschke)

Format

Super 35, cropped to 2:1 aspect ratio.

Cameras

Panavision Millennium XL2 (almost everything)

Arri 435 (Place of Visions, 120 fps)

Arri 235 (Drone shots, Ball game Steadicam shots)

Film Stocks

VISION3 50D Color Negative Film 5203: Rated EI 32. Almost all day exteriors and day interiors. Place of Visions, Lava sword fight at the end.

VISION3 200T Color Negative Film 5213: Rated EI 100 or 80. EI 40 with “scotopic” filter factor. All moonlit scenes that are not mixed with firelight. All firelight scenes that are not mixed with moonlight. Slavic village raid without 85 filter.

VISION3 250D Color Negative Film 5207: Just a couple day exterior scenes in November and December when, in Ireland, the sun is very low, cutting through thick cloud the long way, rated EI 125. Also Mixed firelight/moonlight scenes with cc40 cyan filter, filter factor tests led me to rate this combination at EI 80. Underexposed scene optimistically and mistakenly rated at EI 125.

VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219: Rated EI 250. Berserker bonfire scene. Past vision in the dwarf forge, making the sword Draugr.

Lenses

Primo sphericals, modified by Dan Sasaki to feature round irises, moderate barrel distortion and highlight halation.