The Photography of Charade

An interview with Charles B. Lang, Jr., ASC — who filmed the project on a variety of practical locations throughout Paris.

It was only natural that the romantic suspense comedy Charade should be filmed in and around Paris, since the City of Light has long been regarded as a symbol of romance and adventure.

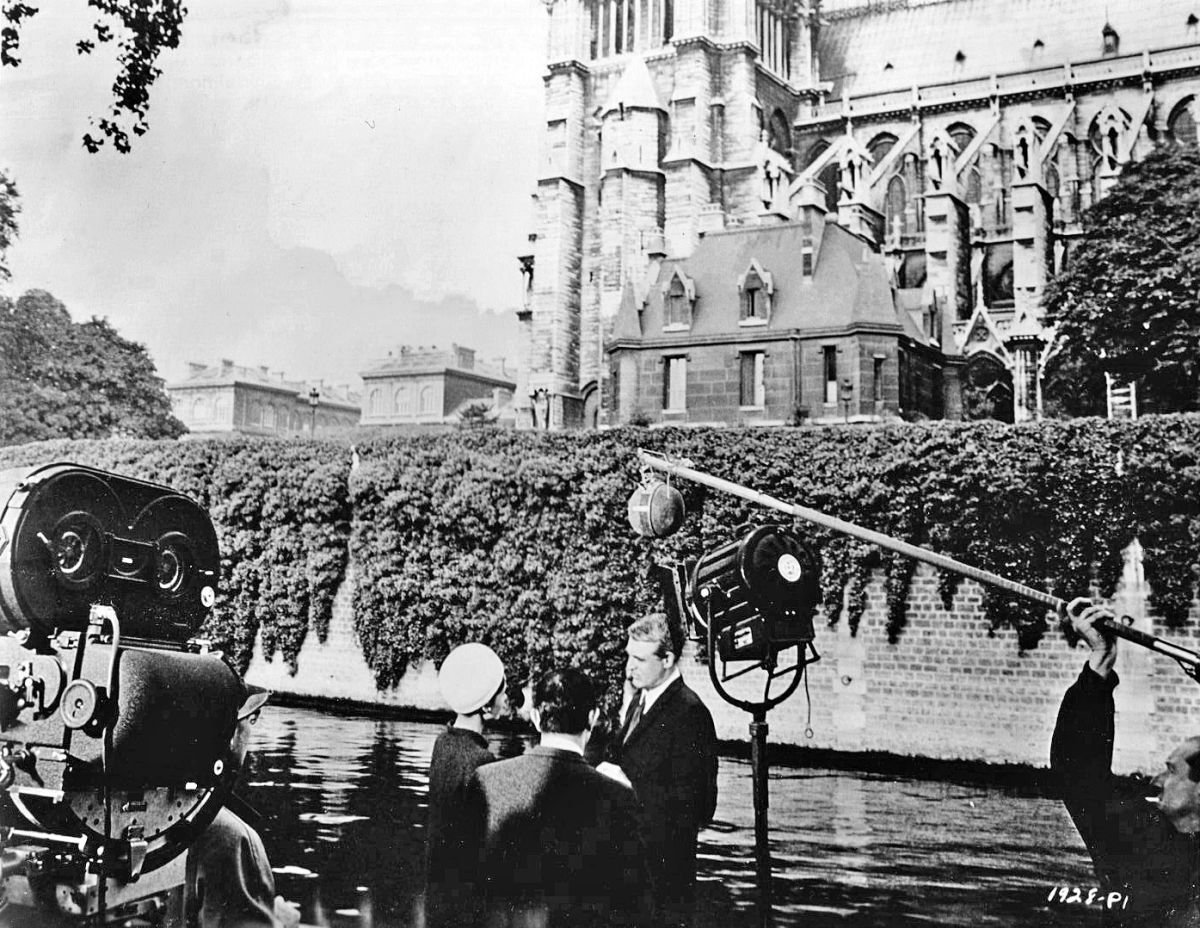

For director of photography Charles B. Lang, Jr., ASC, the color photography of this suspenseful “chase” film was a stimulating challenge, since a great deal of the action was photographed against actual Parisian backgrounds such as Les Halles, Notre Dame Cathedral, the Rue Scribe, the colonnades of the Palais Royale, and in and around the actual subway trains of the Metro, Paris' famed underground railway system. Many of the interiors in the film, as well, were photographed in actual locales.

For the spectacular ski resort snow sequences, the Charade company, which included a cast and crew of 60 people, trekked to Megeve, in the French Alps. Twelve truckloads of equipment were hauled over the Alpine roads: lights, generators, costumes — plus “cover” sets in case bad weather should prevent the company shooting outdoors. A huge garage had been rented in advance where indoor sets could be erected in case it became necessary to shoot around poor exterior conditions, thus keeping the production on schedule.

Megeve, some 400 miles from Paris in the shadow of Mont Blanc, is at an elevation of 3,500 feet and one of the continent’s swanky winter resorts. Surrounded by towering mountains, the locale provided spectacular backgrounds for the action along with several difficult photographic problems.

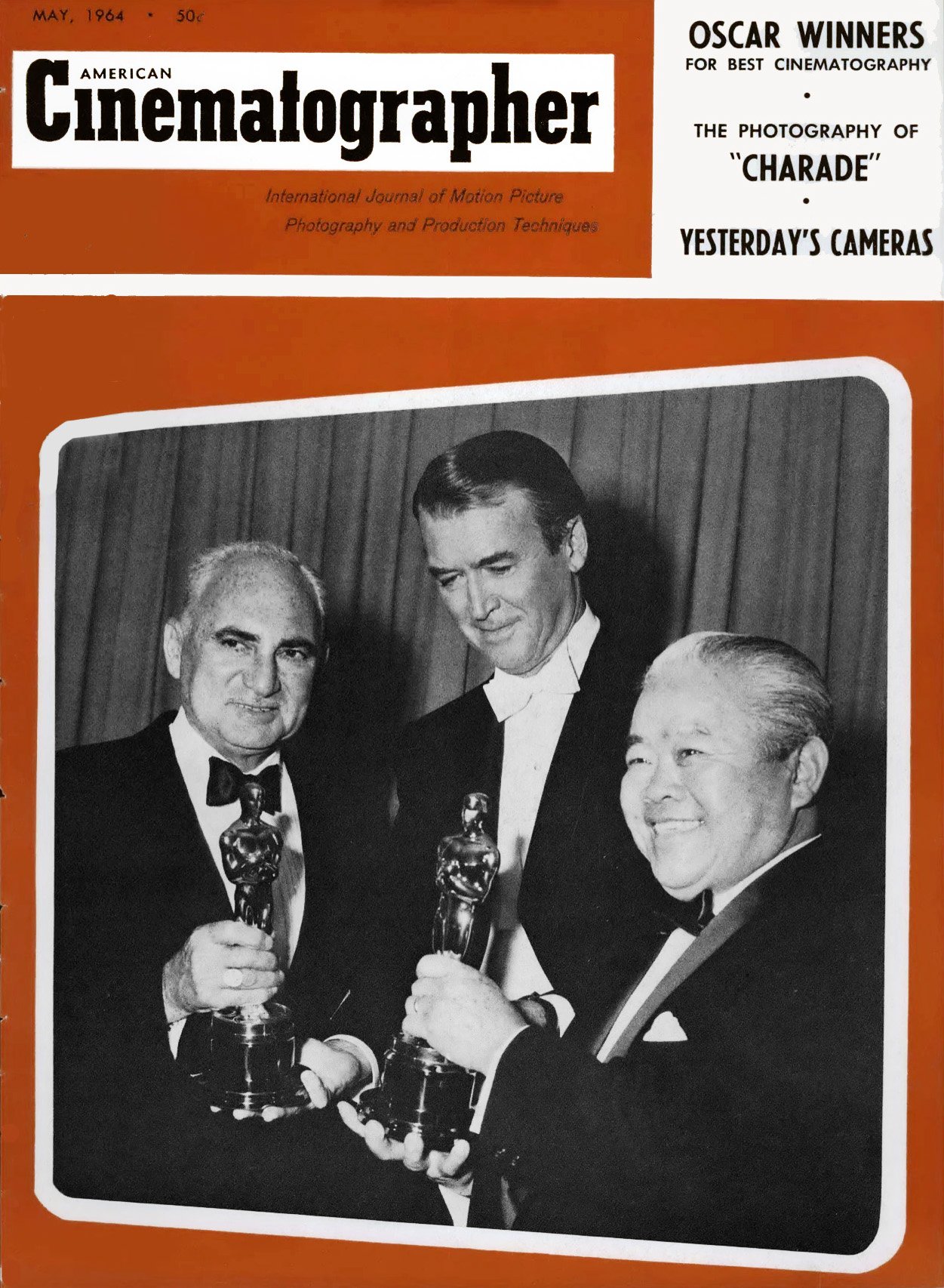

Academy Award-winning cinematographer Lang has received 16 nominations for the coveted Oscar, the latest for his spectacular photography of the hair-raising “shooting-the-rapids" sequence in the Cinerama feature, How The West Was Won.

Best known, perhaps, for his virile photography of such rugged western dramas as Gunfight At The OK Corral, Last Train From Gun Hill, One-Eyed Jacks, and The Magnificent Seven — he is considered one of the most versatile cameramen in the industry. As evidence of this, besides Charade he has recently completed photography of a David Lean-directed segment of George Stevens’ Biblical panorama The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Interviewed at Universal Studios on the set of his current assignment, the Cary Grant-starring wartime romance Father Goose, Lang discussed many of the problems encountered in filming Charade, as well as the techniques he used in overcoming them. The highlights of this interview follow:

American Cinematographer: I understand that you were already in Paris when filming was started on Charade, having just wound up photography on Paris When It Sizzles. Did this offer any technical advantages?

Charles B. Lang, Jr., ASC: Yes, it was actually quite a break, in that I continued to work with one of the same stars, Audrey Hepburn, and with substantially the same French production crew I had on the other picture. They were used to me and I to them, and we got along fine — even though I never learned French much more than to say a few words and talk with my hands. But they were a fine bunch and we worked very well together.

What differences did you encounter in French equipment and technical methods?

Mainly, I had to get accustomed to the kind of equipment they use for shading lamps. The electricians there do the work that our grips do here in goboing lights, and they have a unique device that they clamp directly onto lamps. It’s sort of a gobo arrangement with an adjustable long arm and different types of shades that they can twist around and angle. They don’t have separate stands like the ones we use for gobos, shades and the cuckoloris. They work everything off the lamp itself, clamping shades onto the lampstand and pushing them out in front. I am used to having the shades farther away from the lights so that I can get a little sharper shading, but I learned to work with what they had.

What special lighting problems did you encounter in shooting inside actual location interiors — such as the theater in Charade?

Well, you find that you can’t spend forever tacking up lights. You do the best with what you have and you put the available light in the very best possible places to create good-looking lighting. Working down in the Metro subway was quite a challenge because when you’re shooting down there you have a problem of concealing the required lights. You’ve got to find a way to do it. You do some shading and some fixing and aim to keep the lighting as realistic as possible. It’s the only way you can shoot such location interiors. Sometimes, strangely enough, it comes out better than expected. I think all cameramen will agree that often it’s tougher to shoot actual interiors and natural locales, but you become more ingenious and somehow the light actually looks better than if you had everything at your command and could take the easy way out. Pitting a light on the top of the set and beaming it downward is really a phony light most of the time. On location, you don’t use it because you can’t. You have to resort to your ingenuity and work out something from the floor that will give you the desired modeling and interest.

Shiny white, which was a very difficult situation because we couldn't dull or tone them down. So we just shot it that way. All you can do in a case like that is fix your lights so they won’t reflect too much.

What kind of lighting units did you use on these locations?

I found that Mole-Richardson had available in Paris lighting equipment as good as any I have used in Hollywood. They furnished a full line of lights — including big cone lamps for soft illumination, the shadowless reflective type which are so useful in studio-set lighting.

The final chase and gunfight sequence among the colonnades of the Palais Royale had a very sinister photographic mood. What lighting approach did you use to achieve this?

I used lots of black shadows created by cross lighting as much as I could and still have the actors look well, the ones who were supposed to look well, that is. Sometimes we cross-lit the background and lit the actors in the front with a softer light so they were attractive. You come to know their best lighting and angles. We try our best all the time, no matter what kind of conditions, to make the players look attractive. When using a harsh cross-light, we’ll shade it a bit where it hits an actor’s face or we’ll shade part of it, eliminating whatever is unattractive, and fix it so that it is attractive. Sometimes, with rugged male stars, we have to switch over and purposely make them look stronger by using what we call a “sculptured” style of lighting.

The style of lighting used in Charade was necessarily quite different from the style you used in the '‘gutsy” westerns you have filmed. Do you have any difficulty switching from one style to the other?

You have to be able to switch photographic styles every time you do a new picture. If a photographer like myself goes from a western, like One-Eyed Jacks to a romantic comedy with Audrey Hepburn, you have to switch. You can't stick to one system. And it’s interesting, too, that you do change your methods and style.

It was quite a change for you, going from One-Eyed Jacks to Charade, wasn’t it?

They were two very different types of pictures. I’m strong for photographing dramatic westerns like Gunfight At The OK Corral, where you don’t have to worry if a line shows in a character’s face. It’s easier, much easier, as a matter of fact, if you don’t have to worry about how the people look. You can cross-light them, and get dramatic effects — but when you have to get dramatic-looking things and still have the people looking well all the time it becomes a real challenge.

In terms of technique, what are some of the specific adjustments you must make in switching from one style to another?

To photograph a gutsy picture like a western, right off the bat I’m going to get the shots as sharp as possible by stopping down the lens. I'm going to work with effect lights as much as I possibly can, cross-lighting and so on. It shows up defects, but in this type of film we look for defects; we purposely try to accentuate them by means of the gutsy kind of photography. Then when I switch to a romantic type picture — I switch to softer lights, more diffusion, so that any facial defects won’t show as much, and I try to get as flattering a light as possible on the person. I use much less cross-light. When I use front light I have to use more shadowing — with gobos and that kind of thing, and thus avoid flat photography.

To make a player look as attractive as possible in a “romantic” sequence, what are some of the methods you use?

First I study the actors, particularly their noses and other features. There are certain basic formulas that pertain The light closest to the lens shows the least defects — wrinkles and that sort of thing — but many times, too, it does not work out well, because if a person has a very broad face and you throw a front light in, it flattens the face and makes it look just that much broader. With the player who has a wide face, I try to use a bit more cross-lighting. I d say that 75 percent of the time a woman looks better when photographed with the lens a little above her eye level, and shooting down. Men, as they get older, look better from a higher camera angle, because they usually get a little “jowly.” If they are young men, low angles are best. Low angles give young men a heroic look. I’ve always tried, in most westerns I’ve shot, to use a predominantly low-camera technique because it makes men look rugged, big and strong. As they get older, you want to hide their heavy necks and so you use a higher camera angle and aim down at them.

Getting back to Charade, what would you say was your greatest challenge in shooting at the Megeve ski resort?

Well, the indoor swimming pool sequence was really a problem because it was enclosed with glass, and it became a problem to use lights in there without picking up reflection and glare from the glass. It became a matter of lighting not the way you wanted to, but hiding lights at one side, enabling the camera to miss any reflections. We couldn’t even open windows; they would fog over because of the ice-cold air outside and the steam from the heated pool inside.

Did you use any special type of lighting equipment to shoot that sequence?

No. We used Brute arcs to balance the daylight, because our characters walked right outside from the swimming pool. This meant that we couldn’t use incandescent yellow light. We had to use cool blue light either from arcs, or by means of Macbeth filters; so we used Brutes.

What about the balance of intensity between the artificial light and the exterior light?

I think we balanced to anywhere from half-a-stop to a full stop overexposed for the exteriors compared with the interiors — that’s about par with color — about a half to a full stop. If you go much more than that the results get kind of “flarey” outside and you may lose all detail on the snow-covered mountains.

Those sequences on the terrace overlooking the ski runs — they were all the real thing — no process shots?

They were all shot right on location and it was difficult, too, because we had to build extremely high parallels over the edge of the cliff in order to get the lights and camera into position for shooting the reverse angles — shooting over Cary Grant’s shoulder toward Miss Hepburn, who was right up against the rail. Straight down below there was quite a drop, so we had to build parallels strong enough to hang out into space.

Did you encounter any bad weather while on location at Megeve?

While we were up there we had a blizzard that lasted for several days, so we built an interior “cover” set. The set represented the nightclub lounge where Audrey Hepburn runs downstairs to make a phone call and carries on a lengthy scene in the phone booth. The company built that little room with the phone booth in a vacant garage — and believe me, it was mighty cold working there.

I was thinking as I watched the sequence shot at Les Halles, the Paris produce market, that you must have encountered some unique problems shooting in those cramped quarters.

Yes. As you may remember the “heavy” talks to Audrey Hepburn on the phone and agrees to meet her there. We showed them walking along, intermingled with the market workers. As they walked Hepburn’s companion mentioned the meat market, and we showed a flash of the market with all the meat hanging there. That scene actually was shot right in the market. It was pretty tough going. We were working in a narrow alley, with no room to hang lights except on the camera. We hid a few lights in doorways and tried to make it look like the actors were walking in and out of the natural light of the place.

As I recall, the camera trucked right along with them, didn’t it?

There was a trucking shot made as they walked through the market; you could see people, dimly, right behind them carrying vegetables or other produce, getting crates out of trucks, etc. We laid plywood boards on the ground so the crab dolly would have a smooth base to roll on. We had a fine crab dolly, this time — just like those we have here in Hollywood.

Did you find the maneuverability of the crab dolly to be a special advantage?

Yes, I like the crab dolly. I try to use it as much as possible. I like the small boom, too, but it takes up more room and you have to take out wild walls more often than when using the crab. 1 do almost all of my work from the crab dolly. It’s a wonderful development, quick to maneuver, and enables one to get the camera into position quickly. It’s one of the really good tools that we have to work with.

What about the format and processing of Charade?

The film was shot in a 1.85 aspect ratio, using the full aperture. In printing, Technicolor reduced the frame optically to Academy aperture proportions. In Paris, we could see our rushes every day, thanks to the LTC Laboratory — which is an excellent one, by the way. They processed our negative and daily prints. Technicolor did the release printing.

What is your feeling about the use of colored gels over the lights in color photography — let’s say, to warm up or tone down faces?

Most of us leave that up to the laboratory. We try a little of it, but the lab can exercise better control than is possible on the set.

From my own experiences shooting in Paris during the winter, I’ve found that the leaden skies created an exterior light problem. Did you have any difficulties of this sort?

We were shooting in the wintertime, and we found that in Paris, it was so dark that we could hardly get exposure at f2.8 with an ASA 25 film speed. Most of the time we were shooting at f2.8, wide open, and only printing around 11 at f2.8. The night scenes in the picture we shot with a Japanese lens at T2.

I was especially impressed with the photographic quality of that beautiful night sequence in which the main characters journey on a festive riverboat down the Seine. What special problems did filming these scenes present?

Well, I waited until it was practically dark. In Paris, there’s a long period between daylight and dusk. When the light looked right to me I started shooting. Fortunately, I hit it at just the right moment. I didn't want to shoot early because I was afraid that by the time we got the boat back it would be too dark, and I knew that I would only have one run at it; so I waited until it was practically black, just a faint blue in the sky. Then I shot the scene with this Japanese lens, wide open at T2. We used just the normal lights on the boat going under the bridge. Of course, the scenes on the deck of the boat were made with process plates, which we shot with the same lens under the same conditions so that the whole sequence would match evenly.

What means did you me to gauge exposure for the actual location shots of that sequence?

I knew that the boat itself had enough illumination on it and would be all right, but I didn’t know how dark the sky should be in order that it would look like night, and still retain a little silhouette value on the buildings. I just had to judge it by eye. With a fast lens, I could let the sky go right down to a point just before it got completely black, if necessary.

Just for the record, how long have you been working in the motion-picture industry?

Quite a long time. I started in the business right after I left USC Law School in 1921. I began as an assistant operator and finally got my chance as director of photography in 1930 with Paramount. My first Academy nomination came in 1931. Then, in 1933, I received an Oscar for A Farewell to Arms.

Of note, Lang was just 28 when he earned his first Oscar nomination, and 30 when he won.

After shooting Charade, he would go on to earn two more Oscar nominations (totaling 18), for his camerawork in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) and Butterflies Are Free (1972), finally retiring in 1973.

Lang was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991 and passed on April 3, 1998.