The Photography of East of Eden

Ted McCord, ASC was chosen because Elia Kazan wanted no “formula” cinematography.

This article was originally published in AC, March 1955

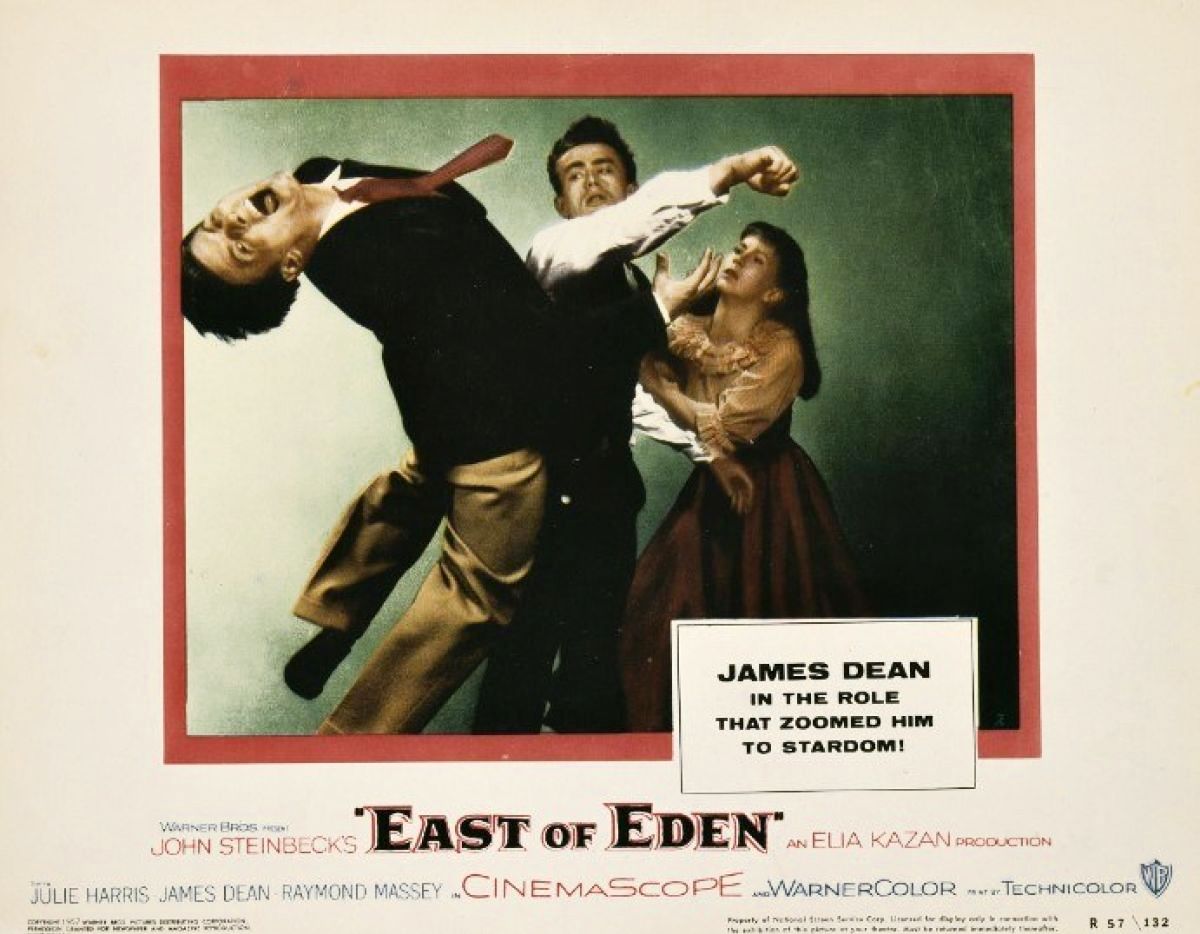

East of Eden, which Elia Kazan produced and directed for Warner Bros., is a picture that will be talked about for a long time to come. From start to finish and in every department it is a superlative accomplishment; it will be prominent a year hence for the number of nominations for Academy Awards it unquestionably will receive.

When John Steinbeck’s East of Eden was published in 1952, it was acclaimed by the public and the critics as one of America’s great novels. The motion picture is based on approximately the last fourth of this monumental novel about two families who settle in Salinas Valley, California. The action of the film takes place in 1917 and depicts the clashes of personality between Adam Trask, a devoutly religious man (Raymond Massey), and his twin sons, Cal (James Dean) and Aron (Richard Davalos). Both lads fall in love with the same lovely girl, Abra (Julie Harris), who is a classmate of theirs at Junior College. How the two sons react when they discover the shady occupation of the mother they had believed dead since their infancy is dramatically presented.

“You’ve got to be bold, and brave, too, to work with Kazan, for he’s that kind of a man himself.”

— Ted McCord, ASC

Kazan spent months in selecting the cast for this picture from actors available in Hollywood and New York. The majority of the actors he finally chose are relatively unknown to motion picture audiences. Kazan’s criterion was not to obtain name stars, but the actors best equipped to give the most realistic interpretation of their particular roles.

And he followed the same approach in choosing his director of photography — Ted McCord, ASC.

When Kazan told Ted the picture was to be filmed in CinemaScope and color, the latter wanted to withdraw from the assignment, saying that despite his long career as director of photography, he had never photographed a picture in CinemaScope, and had done nothing important in color.

“All the more reason why I want you,” said Kazan. “You won’t have any preconceived notions about CinemaScope and color. You won’t be following formulas, but will be more inclined to use your imagination, to freely explore and create. And that’s the kind of photography I want for this highly dramatic and unusual story.

Much of the picture was shot in the actual locale of the novel in Salinas. Here, in a district known as the world’s salad bowl, the sequences were filmed in which Adam embarks on his ill-fated lettuce refrigeration project.

In nearby fields the scenes in which Cal is nursing along his bean crop were photographed. The shooting of these scenes were synchronized with the farmer’s planting so that the bean crop would be precisely three inches in height at the time filming began.

For the sequence which shows the freight train loaded with Adam’s crudely refrigerated lettuce, arrangements were made with the Southern Pacific Railroad to secure a locomotive which actually had made freight runs through Salinas in 1917. This grizzled veteran of the rails had traveled approximately 37 million miles before making its screen debut.

The exterior scenes in the town where the boys’ mother, Kate, operates her gambling house were photographed in the picturesque little town of Mendocino, California, in the heart of the beautiful redwood country

Though as much shooting as possible was done on location, considerable work remained to be done at the studio. This involved the building of elaborate sets designed by art directors Malcolm Bert and James Basevi.

Since in up-to-date, 1954 Salinas television antennae and other marks of modern progress are omnipresent, a replica, of Salinas as the town looked in 1917 was constructed on the Warner Bros. backlot. The shops were built in the same wooden style then in vogue and their shelves and showcases were stocked with the type of merchandise in use during that era.

All this took very careful research. Research department heads spent several weeks in Salinas gathering old photographs and information from the citizenry about the town as it was prior to our entry into World War I. The information gave authenticity and verisimilitude to the recreation of 1917 Salinas at the studio as well as to the staging and photographing of such events as that World War I parade.

These locales represented the key sets and scenes of the picture on which director of photography McCord focused his attention in the early stages of planning the photography. The venerable facades of the World War I era. the simple life of those days, the sedate decor of interiors of the day — all these factors had a bearing on the photographic approach that was to be given the production.

The picture is not long on the screen before the striking artistry of McCord’s cinematography comes sharply to one’s attention. It is reminiscent of the imaginative camera work that marked Johnny Belinda, which won McCord an Academy Award nomination in 1949.

Perhaps the most startling innovation is the way he tilted or angled the CinemaScope camera in order to achieve a more compelling composition when shooting the dramatic scene where the father is having a heart-to-heart talk with his troublesome son, Cal. The two are seated at the family dining room table — the father at the far end, and son at the side, in left foreground. To bring the two dramatically into prominence in a tight, widescreen closeup, McCord moved his camera around to place the table diagonally in the CinemaScope frame, then tilted the camera to one side so that the wide rectangular area of the CinemaScope frame would tightly fit the composition. In this way, the father was given visual dominance in the scene that could not have been accomplished in any other way. It is something that never before had been tried with the CinemaScope camera, undoubtedly because of the ultra widescreen format. McCord’s imaginative treatment here sets a pattern sure to be followed by others.

He used the tilted camera technique in still another scene, too. Later in the picture, there is a shot of Cal swinging in a garden. Instead of shooting the scene head on, with the boy swinging alternately toward and away from the camera, McCord set up his camera a little to one side, so that the wide CinemaScope frame encompassed the arc of the swing, keeping the boy in fairly close focus. As the boy swung forward, the camera, mounted on a free-head, was angled and tilted to keep the swing action within the frame, giving an unusual photographic effect to the scene.

This is the type of imaginative photography which director Kazan invited of McCord when he gave him free rein to develop bold new treatment in the filming of East of Eden. Kazan would often call McCord to one side and tell him, “If you see something you can do to improve this scene, I want you to do it. Figure it out, then call me when you’re ready.”

Although it was Kazan who in the beginning sought the bold, the realistic and the unconventional treatment in the photography of East of Eden, it was Ted McCord who more than once, having caught the spirit of the thing from Kazan, steadfastly held to the credo first established by him. “You’ve got to be bold, and brave, too, to work with Kazan,” said McCord, “for he’s that kind of a man himself.” So when McCord chided him at one time for wanting to shoot scenes “both ways for protection.” Kazan was persuaded to follow the bold and unconventional camera treatments which the daily rushes had already shown to be highly successful.

East of Eden is punctuated with many unusually dramatic photographic treatments about which limited space precludes describing here. But there is another instance where McCord’s imagination paid off that resulted in a simple effect, obtained in a method that is almost as old as cinematography itself.

Kazan wanted a “spooky” effect in the photography where the camera was to capture action of the boy Cal in his bedroom. McCord suggested shooting the scene through the bedroom window and through the transparent netting that was the window curtain—with an offstage fan gently blowing the curtain to and fro as if it were moved by a gentle breeze. The pictorial effect is most unusual and lends just the right atmosphere to a scene that begins a new dramatic phase of the picture.

In the very beginning — before actual shooting of the picture began — McCord made a number of pre-production tests to determine the most appropriate colors for the key sets, colors that would be in keeping with the precise mood director Kazan felt was so necessary to the motivation of the story theme. For mood was a highly important factor in this picture, a factor that was to underscore the unusual personality of Cal, the strong feelings of the father, and the moods of Cal’s brother Aron and his sweetheart Abra. No less important was the strong pictorial mood that would give the brothel interiors the evil and foreboding aspect so necessary to background the action that takes place there.

Here a unique method was followed. A number of flats were painted or decorated with wallpaper. Then they were photographed in pairs on the test stage by McCord. The flats were paired in contrasts and were photographed under different lighting schemes. The test footage was viewed in the projection room and it was here that the art directors, and Kazan and McCord mutually decided on the most appropriate color patterns and lighting for the various key sets. Here again, the trend was away from the conventional — the “formula” procedures. There was to be no set ratios for the lighting. Color, and mood established through light and shadow, keyed the photographic treatment throughout the picture, even to the most insignificant shot — if it can be said that there was such a thing in East of Eden.

And while we’re on the subject of interiors, special mention should be made of one scene in particular, the hall in Kate’s gambling house, because a great deal of tense action takes place there; but more important — because it is lit with a single lamp — a 10K. This was placed at the far end of the hall, facing toward the camera. As the players move forward toward the camera (in search of the door leading to the mother’s “office”) they appear in silhouette. Still, there was a measure of modelling achieved through some of the light from the 10K lamp, which was reflected by the highly varnished walls and floor of the hall. It was an ingenious treatment of a seemingly impossible lighting situation.

Holding to his credo for genuine realism in the photography of East of Eden, director Kazan early in the planning of the picture indicated he wanted no process shots of any kind. In the shots of Cal riding atop a freight car of a moving train, the CinemaScope camera was mounted on top of the car and the shots made as the train moved through a stretch of countryside. It was while making these shots that McCord and his crew, along with the costly camera, were almost swept off the freight car as it passed under a low bridge. The crew had been too engrossed in attending the camera to notice the train’s rapid approach toward the bridge. Fortunately, the camera cleared the bridge by a scant three inches, and all in the crew escaped without a scratch.

An interesting problem was encountered when the company was shooting exteriors where action takes place in a field covered with wild mustard in bloom — a beautiful scene pictorially, which enhanced the mood for the romantic action; here Abra first reveals her interest in Cal. Despite the great caution taken to prevent trampling of the mustard, the studio greens man was kept busy replacing the trampled mustard with fresh, upright plants dug up in an adjacent field. As with so many wild plants, mustard will not take to transplanting, and as a result the transplants wilted within minutes. The scenes were finally shot by delaying the transplanting until all rehearsals had been completed, then, when the scene was ready to take, the trampled plants were replaced, the action started, and the camera ordered to “roll.”

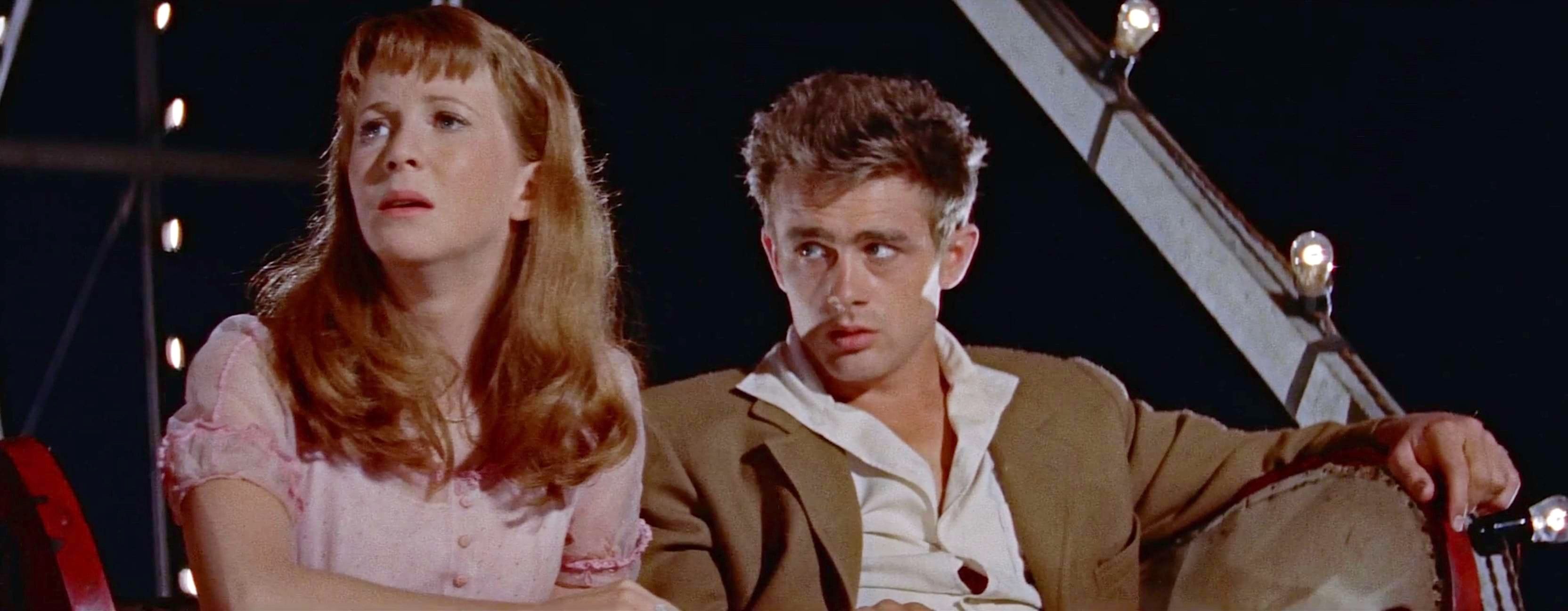

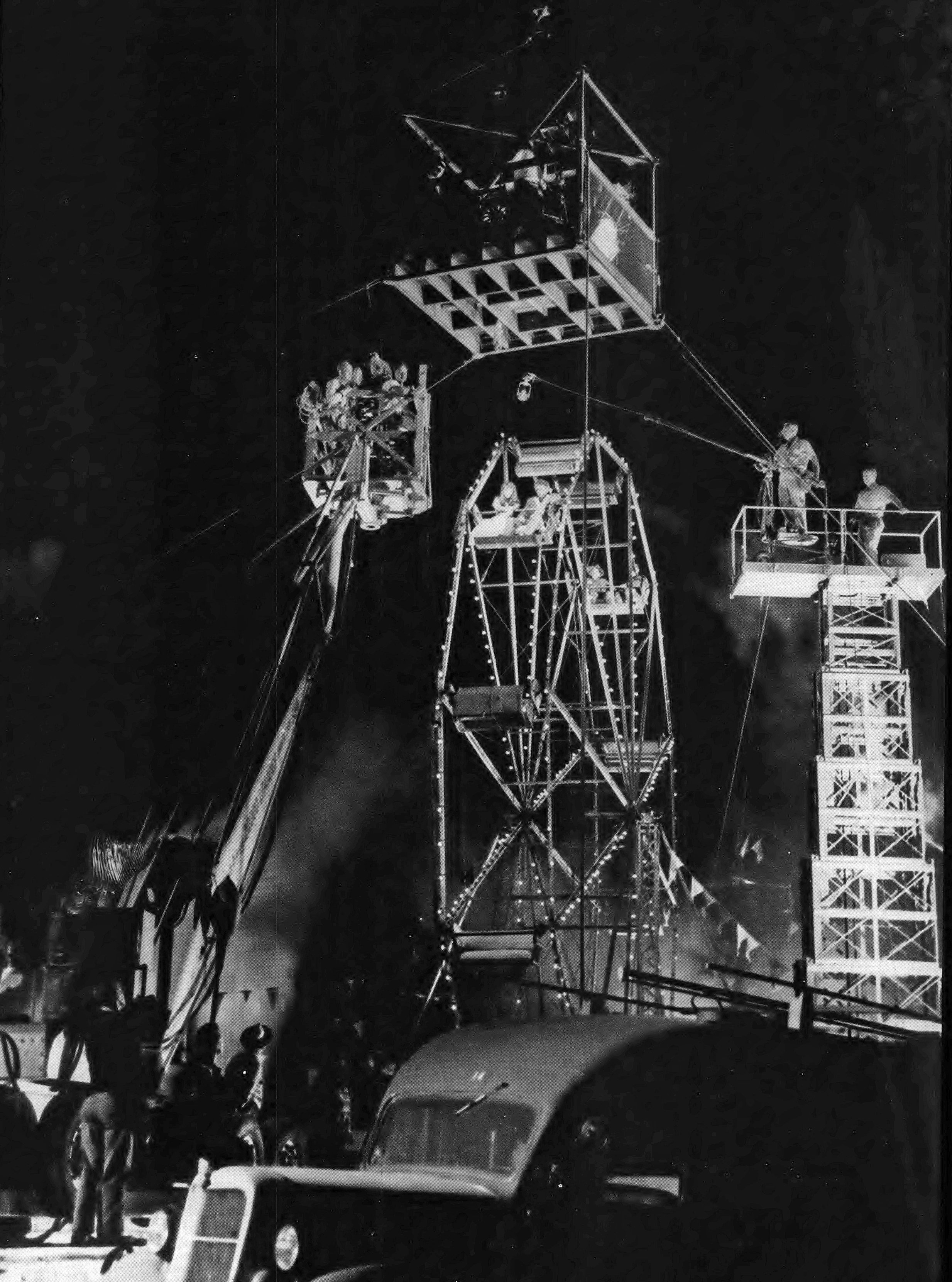

One of the most extensive phases of the photography involved the scenes of Cal and Abra in a gondola atop a Ferris wheel in an amusement park. For this sequence, Warner Bros. erected a Ferris wheel on the studio lot, where shooting could proceed without the interference that normally would be encountered were the action shot in an amusement park. Here is another example of Kazan disdaining the process shot in favor of “the real thing.” Another producer, perhaps, would have played the action on the sound stage against a process background.

To elevate the camera, the giant camera crane Disney employed in filming 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea was used. To provide similar mobility for the sound recording equipment and mike boom, a telescoping parallel on a city power company truck was brought in and the sound equipment mounted on its elevator platform, as shown in the photo [below]. To elevate the necessary lighting units above the top of the Ferris wheel, a giant construction crane was brought onto the lot. From the end of the crane a sturdy platform was suspended and the lamps mounted on it; the power cables were strung up overhead to the supporting cable and thence down the crane to the supply source on the ground.

Mention should be made here of the judicious way high and low camera angles are used throughout the picture; they are not overworked, with the result that when they are used, they give unusual dramatic impact to the picture. Perhaps the most emphatic thing photographically one feels in observing East of Eden on the screen, is that it is an outstanding example of the camera used with proper emphasis. At no time do the photographic mechanics nor the “new look” that marks CinemaScope intrude; rather they add vividness to the interpretation of the script and point up the subtle shadings that are so important in this strong dramatic film of moods and unusual personalities.

McCord’s other major credits include The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Sound of Music and The Hanging Tree.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you’ll find more AC historical coverage here.