The Pit and the Pendulum: A Study in Horror Film Photography

Discussing the set design and lighting techniques in horror filming with the makers of the film.

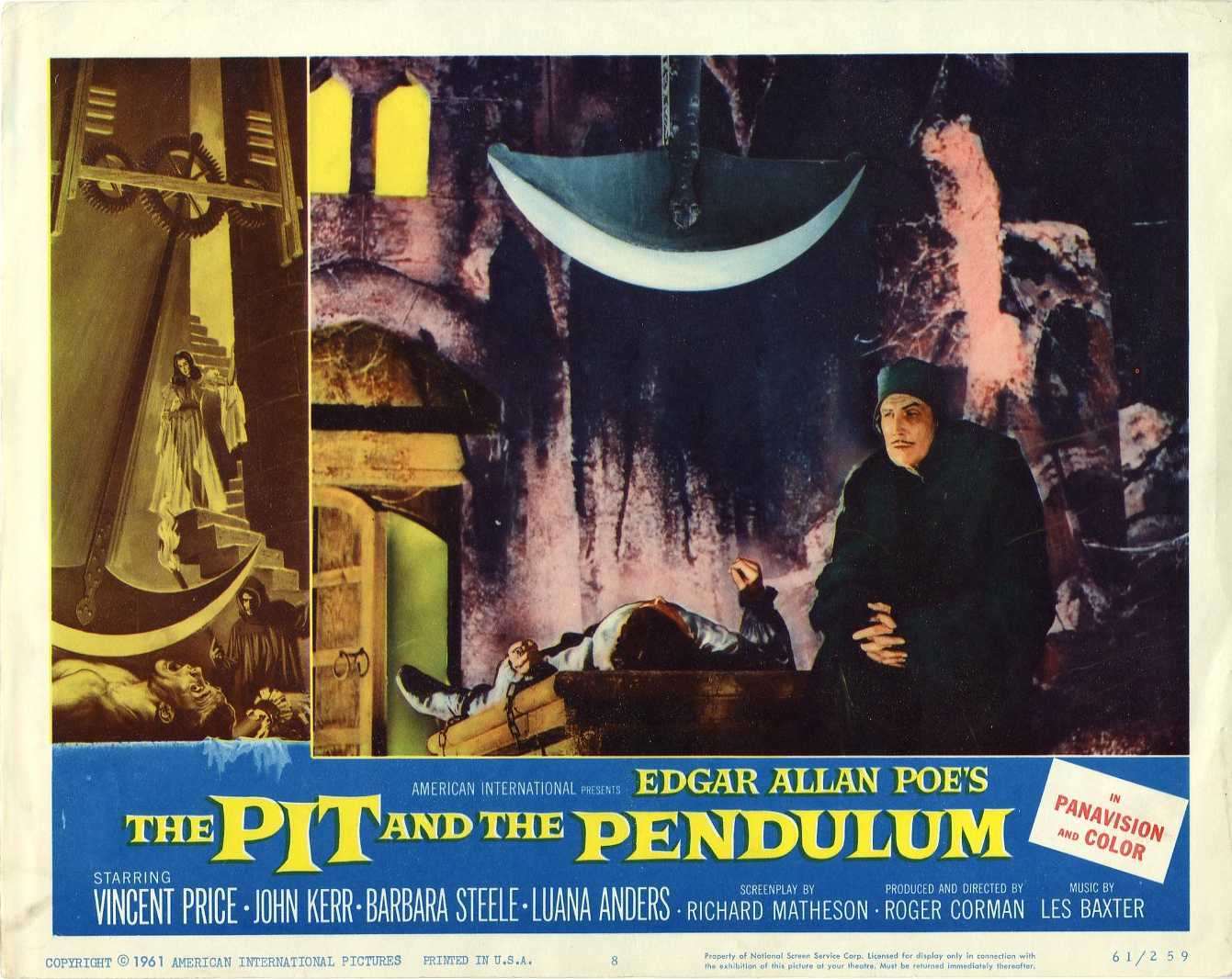

Produced by Roger Corman for American-International Pictures, The Pit and the Pendulum proves that a big picture can be made on a modest budget — especially when it is carefully planned and the creative talents involved are given unlimited opportunity to create.

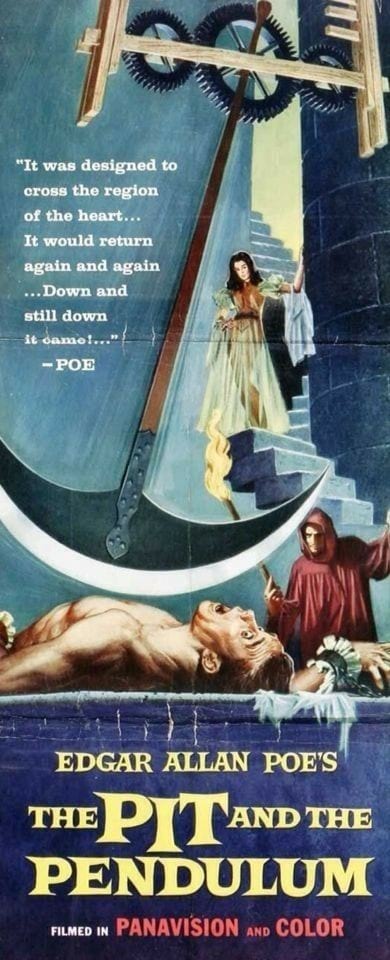

Based on the famous Edgar Allen Poe horror classic, the film is lavishly mounted and imaginatively photographed by Floyd Crosby, ASC. Except for a prologue consisting of exteriors, the story’s action takes place entirely within the forbidding confines of a medieval Spanish castle replete with massive main hall, ornate bedrooms, secret passages, dungeons, tombs, torture rooms and, of course, the formidable “pit” with its massive stone altar over which is suspended the swinging pendulum blade used to torture and sometimes slice up hapless victims placed beneath it.

“Thanks to pre-production planning and rehearsals, there was no time wasted on the set in haggling and making decisions.”

— Roger Corman

Except for the absence of big name stars in the cast, the film boasts production values comparable to pictures costing five times as much.

“We achieved what we did on a low budget because we carefully planned the whole production in advance of starting the cameras,” director-producer Corman explains. “Thus, when we moved into the studio for 15 days of scheduled shooting, we didn’t have to start making decisions. Because of our pre-production conferences with director of photography Floyd Crosby [ASC] and art director Dan Heller, everyone knew exactly what to do, barring any last-minute inspirations on the set.

“Previously, I had painstakingly rehearsed the actors so there was complete understanding as to what each was to accomplish in each scene. This is most important; there is nothing worse than to be on the set and ready to roll, only to find that director and actor have different views as to how the scene is to be done. Thanks to pre-production planning and rehearsals, there was no time wasted on the set in haggling and making decisions.

“In our set design, choice of costumes, and in matters related to the atmosphere of the period of the story, we aimed to be as authentic as possible, without becoming slaves to authenticity. Flexibility keynoted the whole operation so that whenever we believed it expedient, we would heighten certain dramatic and shocker effects. Here, Floyd Crosby contributed some outstanding lighting and camera work to enhance the illusion of realism — which, perhaps, was not so much realism but a suspension of disbelief.”

Much of the film’s effectiveness as a thriller is due to its pictorial scope borne of the production design of art director Dan Heller. Having worked previously with Corman and Crosby on several pictures, he was very much a part of the production team that created The Pit And The Pendulum.

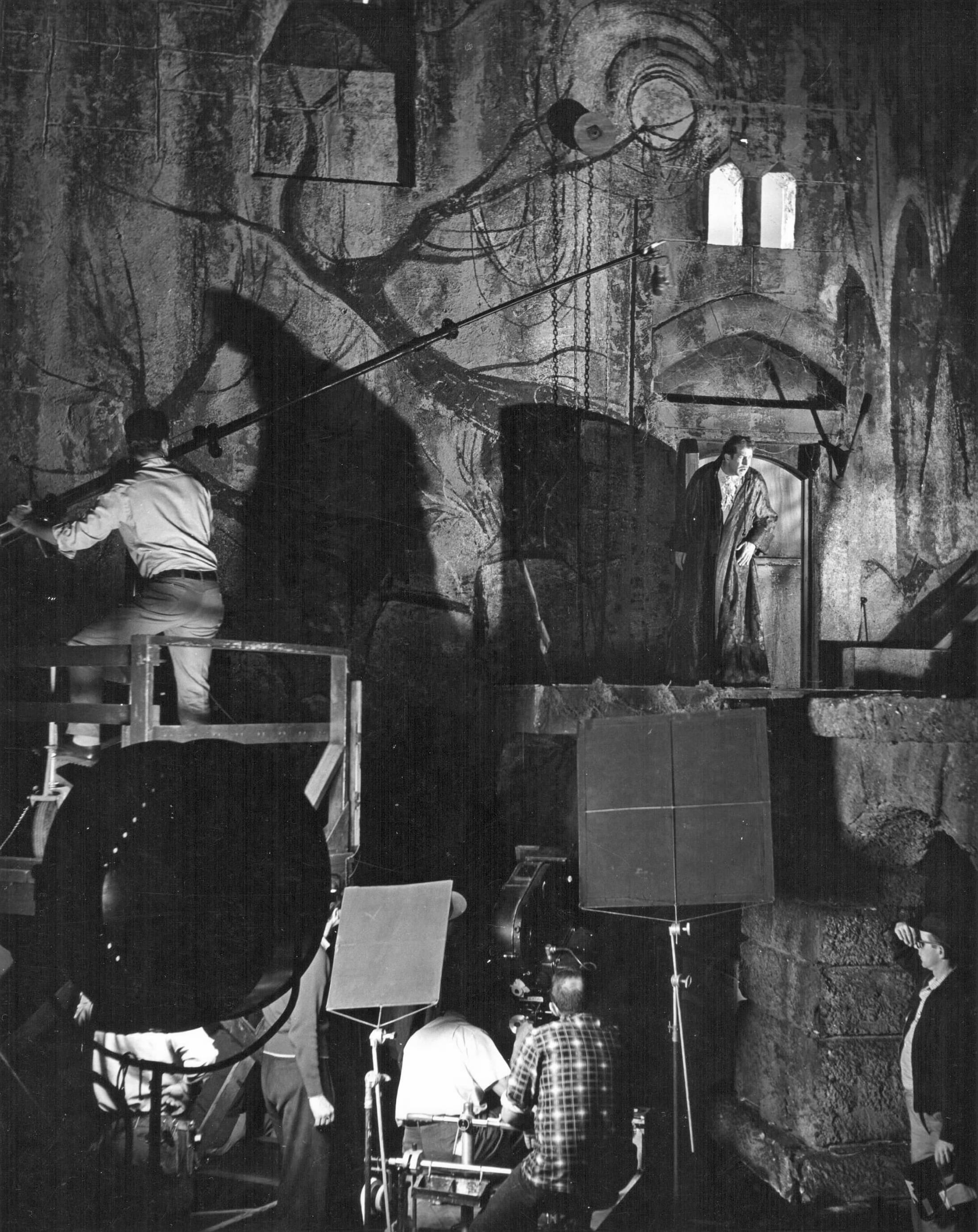

"We wanted a set having many levels and ample space to afford the utmost freedom to the camera,” Heller explains. “Four or five rooms were erected on the stage so they were interconnecting, and we used wide archways and stairways without balustrades. Thus the camera could move freely through the entire series of rooms for sustained takes, if necessary. Massiveness keynoted the design and construction of all sets so that the players would be dwarfed against the vast walls, and in the massive archways, etc.”

Heller’s forbidding split-level castle, with its many rooms, passageways and catacombs occupied four sound stages at the California Studios in Hollywood. Had it been necessary to build the sets from scratch, cost of construction alone would have greatly exceeded the picture’s budget. After Heller drew up the floor plans and made key sketches that visualized how the sets were to look, he next scouted the back lots and prop lofts of the major studios in search of available set units that could be rented and put together to form the sets he had conceived for Pit And The Pendulum.

At Universal-International Studio, massive archways, fireplaces, windows and doorways, and several torture machine props — all from dismantled sets of long-forgotten Universal productions — were available. At other studios, soaring stairways and huge stone wall units were located. From this fund of second-hand set pieces, Heller selected what he needed and had them delivered to California Studios. Here the various bits and pieces were fitted together like a giant jigsaw puzzle, following his floor plans. Though the period of the story was Spanish 15th Century, often a French or German Gothic window was used instead of one of Spanish design because it lent the desired dramatic or pictorial effect. After the rented set pieces had been erected, studio technicians filled in the spaces with appropriate construction to unify the whole. The only set in the picture built in the conventional manner was the dungeon set.

The spectacular pendulum set occupied a whole sound stage and stretched from the floor to the rafters. To heighten the massive aspect of this set, the camera was mounted on a parallel at the opposite end of the stage and a 40mm Panavision wide-angle lens used. This enabled Crosby to frame the scene in his camera with extra space allowed at the bottom and at either side. These areas were then filled in later by printing-in process extensions of the set, effectively doubling its size on the screen.

Other matte shots, following Heller’s original paintings, were used to establish exteriors of the castle. Scenes of waves dashing against cliffs were filmed on the Palos Verdes coast southwest of Hollywood. The camera was locked down tightly for steadiness and the cameraman who was to shoot the matte paintings went along to make sure the perspectives would match.

Photographically, The Pit and the Pendulum is a singular achievement in color mood lighting and the use of the moving camera. To Crosby, who won an Oscar for his photography of Tabu back in 1931, the challenge was one of reaching for top quality under difficult conditions and on a short shooting schedule. Moreover, the entire picture, with the exception of the short exterior opening sequence, required low-key photography, since everything that took place within the castle was in a somber mood. The first half of the action called for medium low-key, while the final half went to extreme low-key with nothing in between for relief.

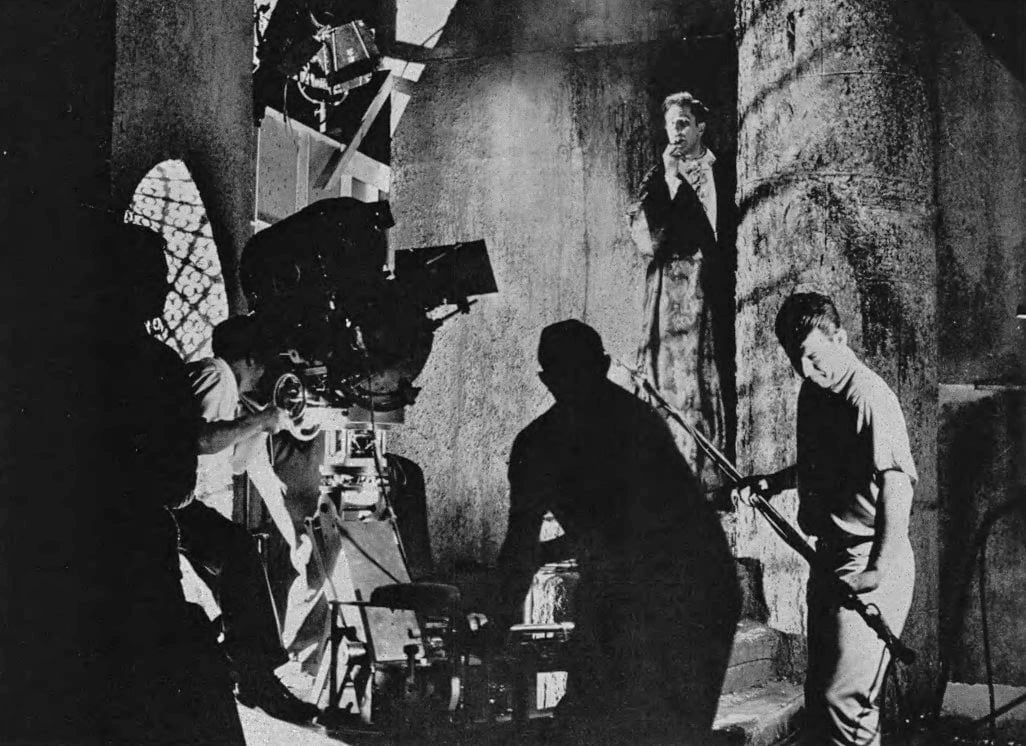

The climactic action of the story is concerned mostly with one actor wandering through secret passages and catacombs, lured by the voice of his wife who is supposedly dead. Most of the low-key effect was achieved in the lighting of the set. A reasonable amount of front light had to be used on the actor’s face, although occasionally it was possible to use just a line light and very little fill. In medium-key sequences, Crosby said, faces were underexposed two-thirds of a stop and the background about a stop-and-a-half. For most extreme low-key shots faces were underexposed a stop-and-a-half. Illumination on the background was lowered to a point somewhere between 15 and 20 foot candles where it would just hardly record on the film.

An important decision made prior to shooting was whether or not to use a flicker effect in the many scenes supposedly illuminated by torch light. Such effects are usually created by placing a fire pan in front of the source light. Crosby knew that if he once introduced the flicker effect he would have to retain it throughout the film. With so very much camera movement and so little time to shoot, he decided to dispense with the effect rather than run the risk of it being inconsistent. In the intricate follow shots his aim was to keep the source light coming from the direction of the torches. There was a great deal of camera movement, most of it done with the aid of a large Chapman boom, with the action often continuing through four or five rooms without a cut. This meant that huge areas of the set had to be precisely lighted at one time.

“The sets were exceptionally well designed,” Crosby observes, “and lent themselves very well to low-key photography. It still amazes me how much set we were able to get on so low a budget. We had some huge sets and, of course, the bigger the set the more lights that have to be rigged, all of which takes time. Sometimes we would get all set to shoot and then get a better idea. In the ‘pendulum’ sequence, for example, we originally rigged the lights high up on the stage, but when we were ready to shoot we realized that making the shadow of the pendulum cut across the figures in the background would be most effective. We had to stop and re-set the lights at a lower angle so the dramatic shadow would not be lost in the depths of the set.”

Crosby displayed a bit of camera magic, born of long years of experience, in shooting the opening exterior prologue — a sequence set at the seashore supposedly against a glowing sky. The day which the company chose for the location, however, had anything but the right mood — bright and sunny with a beautiful blue sky. By using a pola-screen on the lens to darken the sky plus underexposure. Crosby produced the ominous mood called for in the script.

Extremely effective in the film is a series of flashbacks in which the main character, teetering on the edge of insanity, relives traumatic experiences from his tortured past. Realizing that flashbacks can be deadly if they are not well-executed, Corman, Heller and Crosby put their heads together to devise a unique effect that would subjectively convey the character’s horror in dredging up the nightmares lurking in his sub-conscious. They wanted these flashbacks to have a strangeness, a semi-dream quality — twisted and distorted because they were being experienced by someone on the rim of madness who did not know the full facts or was too shocked to recall them accurately. In order to provide a definite visual demarcation between the story of the moment (reality) and what had happened in the past, it was decided to shoot the main story in full color and the flashbacks in monochrome since, as many psychiatrists maintain, most people dream in “black-and-white.”

The flashbacks were accordingly filmed in monochrome and Crosby utilized wide-angle lenses, violent camera movement and tilted camera angles to point up the character’s feeling of hysteria. The finished sequences were printed on blue-tinted stock which was then toned red during development — producing the effect of a two-tone image. The highlights went blue — while the shadows (represented by areas where more emulsion was present) held the dye and were rendered as red, producing a realistic bloody quality. To further enhance the atmosphere of horror, the image was then run through an optical printer where the edges were vignetted and a twisted linear distortion was introduced. The result on the screen is one of genuine shock, an almost too-real-to bear nightmare quality starkly suggesting madness and bloody violence. Like the rest of the picture, the flashback sequences reflect thought, careful planning and imagination.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.