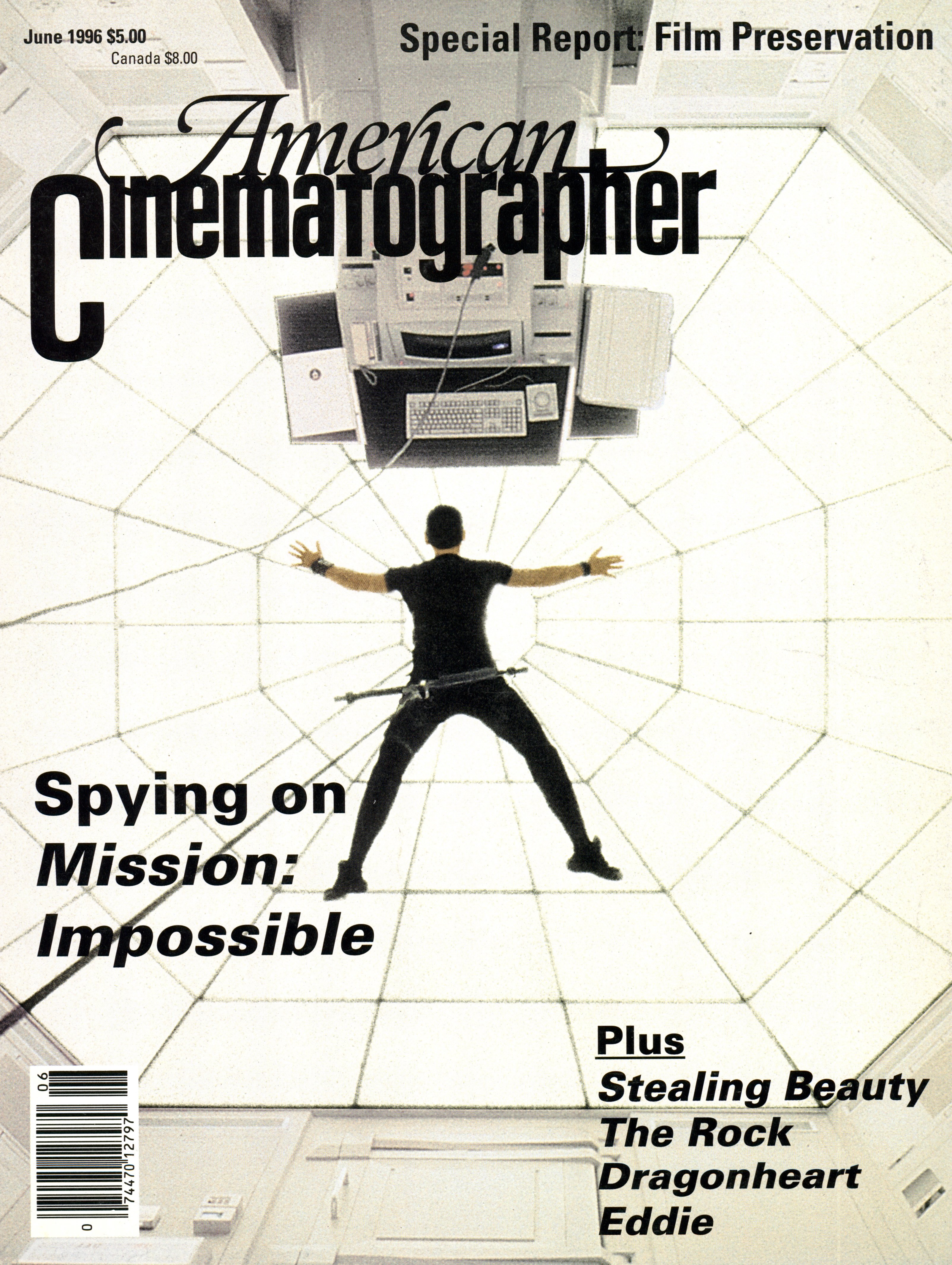

The Rock Offers No Escape

Director Michael Bay and cinematographer John Schwartzman join forces to assault viewers with a hyperkinetic, star-studded action extravaganza.

The Rock is a contemporary hostage drama set at one of the nation's top tourist attractions: the former high-security island prison of Alcatraz. In the film, brigadier General Francis Xavier Hummel (Ed Harris) seizes the island and takes some tourists hostage to force the government to grant full benefits to the families of officers who were slain while under his command during covert government operations. If Hummel's demands are not met, he will launch a battery of rockets filled with highly toxic nerve gas at neighboring San Francisco. Enlisted to save the day are Stanley Goodspeed (Nicolas Cage), an FBI chemical and biological weapons expert with little field training, and John Patrick Mason (Sean Connery), a top-secret federal prisoner who has been incarcerated for years without trial.

Though The Rock may sound like a typical big-budget Hollywood action movie, this $70 million picture offers a decidedly different method of putting exciting, kinetic images on the screen. High-octane visuals are a staple in the cinematic vocabulary of Michael Bay (Bad Boys), the 32-year-old director of The Rock, and he sought extra acceleration from cinematographer John Schwartzman.

"Our approach was to take an image and attack it," says Schwartzman (Saving Mr. Banks). "We shook the cameras a lot in action sequences, by banging on dollies or shaking iris rods. When we used car mounts, I told my grips, 'Keep the bolts loose, we want these cameras to shake.' The action images are at times beautiful, and at times unforgiving in their mood, pace and relentlessness. This film is halfway to being like a Back to the Future-type of theme park ride. Not only will you be stimulated by the story and the actors, but after seeing The Rock, you will want to go home and lie down for an hour because you've just been through something intense."

Schwartzman, a 35-year-old Los Angeles native, completed graduate studies at USC's film school and apprenticed with Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC on 1988's Tucker: The Man and His Dream. He then shot some smaller features before a successful run shooting commercials and music videos for Propaganda Films with such directors as Jeremiah Chechik (Diabolique), David Fincher (Seven), and his former classmate, Bay. Schwartzman later tackled the mainstream features Pyromaniacs: A Love Story, Airheads, Benny and Joon, and the recent comedy Mr. Wrong. The cinematographer had never worked on an action picture before, but Bay chose him because "he is conscientious, a fast lighter and not afraid to take chances."

Says the director, "Benny and Joon was John's best work, but it was so much softer than what I was looking for. I was scared he wasn't going to really push the edge the way I wanted. I kept saying, 'I'm going to be very pissed if we make this movie safe.' Well, he did an outstanding job, exactly what I wanted. It looks very rich, and he wasn't afraid to make it really dark and gloomy down in the tunnels that represent the underbelly of Alcatraz.

"I like to shoot a lot of setups, push the lighting, make things dark, put cameras in odd positions, move the camera with strange dollies and use weird perspectives. The crew on Bad Boys [under cinematographer Howard Atherton] actually said, 'This is never going to cut,' but it did; it's just a different style of filmmaking."

Schwartzman concurs, "On Benny and Joon, we were going for the sense of late afternoon on a lazy summer day, with the sun streaming in through the windows. We tried to paint with light to make all of the characters look a little more romanticized than they really were, and for that movie, it worked.

"On The Rock, we were constantly breaking screen direction and eyeline rules. When Michael says ‘dark’ he means it. I've never worked so close to the edge of blackness, sometimes too close. We worked in the tunnels with three footcandles, but I was exposing for 25. There were no actual lights at all in these tunnels; fortunately, there was a little water kicking a sheen on the wall from the backlighting, so it was not totally black. We used just enough backlight so that you could see the outline of the guys all wearing black at night. There is logic to this; the Army spent $30 million developing these camouflage outfits, so of course, you can't see them!"

The years the duo spent shooting commercials together for Propaganda paid off; they came to the set with an established working method that put them in sync artistically from the get-go. Recalls Schwartzman, "If I saw a room with big windows, I would know instinctively that he would want to bring five arcs through the windows this way. I know the camera's going to be at this end of the room because he's got a great eye and the room only looks good from this side. That allowed me to be ready to go first thing in the morning.

"If I knew we were going to be shooting upstairs in the Alcatraz infirmary, I'd have the scissor lifts in position with either five Dinos or five brute arcs on them, depending on the look we were going for, so when he walked in, the lighting was pretty much there; it was just a case of, 'Where are the actors going to stand and how are we going to finesse this?'"

Schwartzman details, "Our approach to lighting a room was to light it the way the light would naturally fall, and then block the actors around it. We didn't try to fight the natural light, we tried to enhance it. We didn't try to push the boulder up the hill, we tried to ride it down."

The overall lighting design also favored the use of small sources whenever possible. At the same time, Schwartzman wanted to produce enough light to remain at a T3.2 for the sake of depth of field. However, as with the rest of the photographic approaches on this picture, the methods often ended up being unconventional.

Explains the cameraman, "One of my favorite key lights consisted of one-inch mirror tiles Velcroed to a 4' by 4' piece of plywood, off of which we would bounce Par lights. At times this effect would be beautiful and at times unforgiving, but it enhanced the story. We'd also move light sources as if the sun was moving. We didn't want to be too obvious, just a little different. Michael likes to take a sharp point of view. Besides, you could light Ed Harris, Sean Connery or Nick Cage with a road flare and women would still say they were sexy."

Schwartzman acknowledges that Bay not only composed most of the shots, but often operated the camera himself. The cinematographer offers that the director's "intense involvement" in the imagemaking was liberating, allowing Schwartzman to focus all of his energies on lighting concerns. "On a lot of The Rock I would deal with the lighting and let Michael and operator Mitch Dubin decide whether they were going to move the camera up or down 3" from where we had initially set it, and then I'd come back and check it before we rolled," he says.

One explanation Bay has for operating the camera himself is his fondness for the "poor man's process" when shooting actors driving in car chases, which he developed during his music video days. He explains: "There's a major car chase in The Rock in which Connery is driving a Humvee and Cage is driving a Ferrari through the hills of San Francisco. It's a violent, kinetic, and destructive chase. The Humvee is like a tank on wheels; when it hits a car, that car is demolished! I film actors driving in these scenes from a dolly a few feet in front of a stationary car. I do whip pans and whip zooms and violently shake the camera, trying to make the whole screen rumble. Used in snippets, it looks as if the actors are driving ferociously. These driving scenes are normally done on a camera car, but if I'd done that on The Rock it would have looked really lame. I also do this in quite a number of my action scenes. Our operators, who were great, would say, 'Well, you're the best at that, so you should do it.'"

Despite Bay's penchant for fast-paced, quick-cut shots, the various locations in The Rock were rendered in distinct photographic styles. Explains Schwartzman, "The Alcatraz interior sequences are mostly handheld and very edgy, with extreme high and low angles. The scenes in the sewers and tunnels below Alcatraz remind me of the first Alien film. In the Pentagon and the White House, the look is clean and classical. The San Francisco scenes are more traditionally slick, action-picture photography. Overall, the film is a blend of classical widescreen with a hip commercial feel and a lot of visceral, somewhat self-conscious camera movements."

Transferring all of this vigor onto the screen required great energy expenditures from the crew. Schwartzman likens the exhaustion level on The Rock to that of "doing a documentary on Mt. McKinley!" The difficulty of the shoot [six days a week for six weeks] was compounded by the fact that Alcatraz, a Civil War fort built in the 1850s and made over as a prison in the 1940s, wasn't designed with the needs of a film crew in mind.

"On all but the most bizarre of locations, you take for granted that you can at least get a golf cart, a forklift and an elevator," says Schwartzman. "Well, not on Alcatraz. All of the lenses and cameras had to go down six flights of stairs and then a quarter-mile around to the front of the island many, many times; the camera crew got beat up pretty good. I lost seven pounds during the shoot, and that was about average. Just walking from the boat to where we would be shooting most days was the equivalent of climbing up the stairs in a 13-story building. And we moved around a lot, according to the weather, which would often change five times an hour."

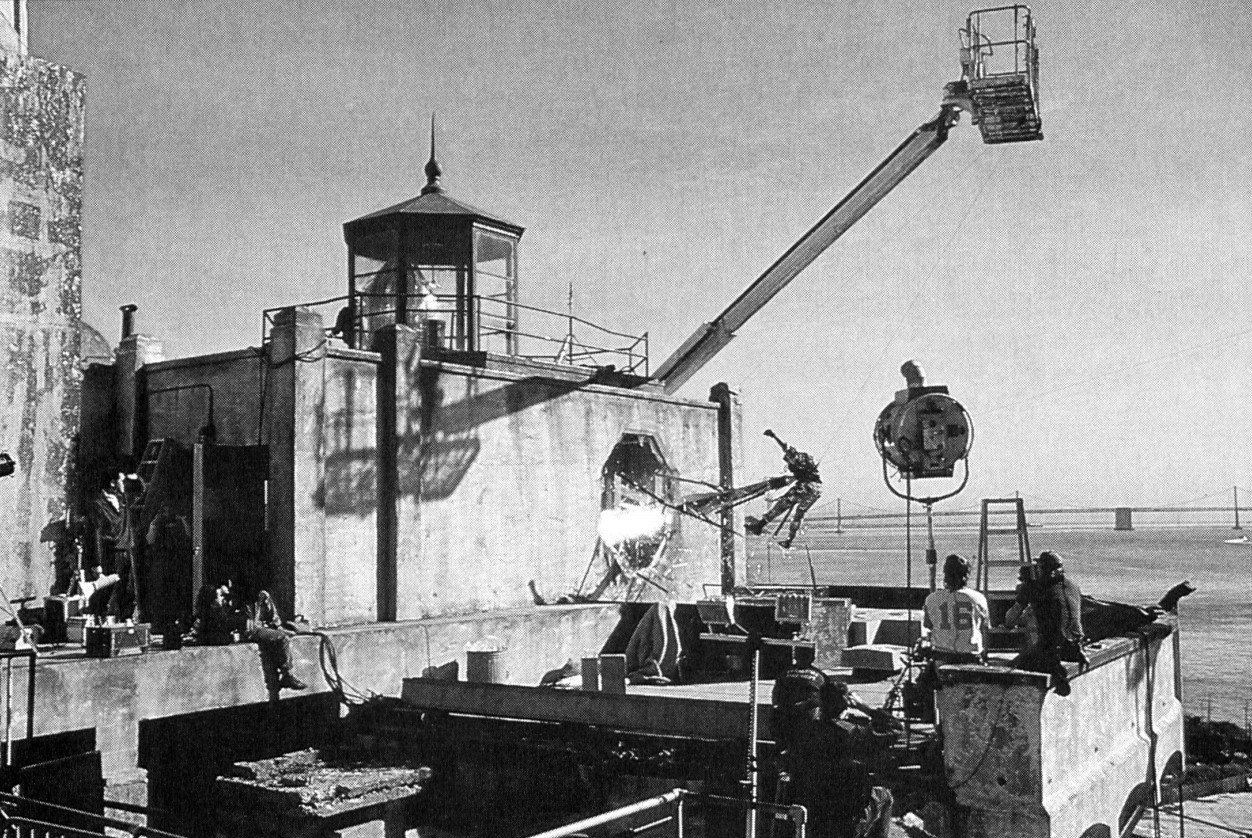

As one of San Francisco's most popular tourist attractions, Alcatraz is inundated daily by tens of thousands of visitors a day, all of whom generate a great deal of money for the city. The Parks Service wasn't about to shut down the site just to suit the needs of the production crew, so arrangements were made to shoot around the teeming tourists. Most areas were off-limits, but on a Saturday shoot, there might be some 40,000 people milling about. The production team was also frustrated by the fact that they were forbidden from altering the prison in any way whatsoever.

"It was like shooting in the Louvre," says Schwartzman. "We were working in a place that we couldn't touch. It's a living monument to the old horrible prison, the paint is peeling everywhere, and we couldn't attach anything to anything there, or scrape off any paint from the interior or exterior. We had to treat it as if it were a Faberge egg. That's tough when you're doing an action picture with machine guns and people running around with hand grenades! We could never say 'Lets put a plate up for a light here.' We always had to find ways to rig that were totally non-invasive."

This "non-invasive" technique required Schwartzman and crew to construct riggings tailormade for the layout of the historical landmark. "As a result, we had to take extraordinary measures. For Alcatraz, we built the weirdest rigs in the world so we could have the camera zipping through holes in the walls," says the cameraman. "My B-camera and Steadicam operator, Chris Harhoff, designed an extra-long 6' Steadicam post so he could run with his Moviecam Compact literally a half-inch off the ground. Jake Jones, our rigging key grip, had to cantilever weights to put a light through a window, and rig pendulums to lower lights over sides of walls, instead of bolting or screwing something into a wall or a ceiling."

"Some days we would shoot only three-eighths of a page, which might require 37 setups because that is how Michael shoots his action, or because it is was a complicated sequence, such as Nick Cage disarming a bomb. Other days we would shoot four pages in two-thirds of a day; for example, if it was a walk-and-talk around the island and we did it on a Steadicam. We had actors who could play those scenes in one take. You didn't have to find ways to work around them; their artistry and professionalism let us do whatever we needed. With actors like Sean, Nick and Ed, and crew members like Chris Harhoff, we could put the 40mm on and say, 'Let's walk from here to here, do this whole scene, punch in for two singles here and call it a day.'"

Bay's desire for scope demanded the use of extremely wide lenses. This, coupled with the impractical location, called for creativity in the placement of fixtures. "There was not a lot of room to hide our special riggings because we used the 17.5mm and the 21mm lenses so much," Schwartzman says.

To accommodate the breakneck pace of Bay's aesthetic, Schwartzman had to run multiple cameras constantly, even for those scenes low on the kinetic quotient. "We always ran multiple cameras — at least two, often three, and up to as many as nine. That is not something I, or any other cinematographer, loves to do, especially since a lot of times the A-camera would be outfitted with a 17.5mm lens and the B with a 150mm or a 300mm. But because Michael has such a strong sense of what he wants to do, he was always looking for very specific snippets from the additional cameras. I might have a 17.5mm master plus a 300mm shot of a guy's hand dialing a phone that Michael knows he's going to need. It's not like we were getting double coverage all the time, but we were always picking up pieces that way.

"Michael was always trying to work in a third camera, until I would finally say, 'No, you can't.' Many times the B-camera would suffer, because, of course, the shot was lit for the main camera. Michael promised me that if something he wanted from the B-camera didn't look good, he wouldn't use it. He'd say, 'I'm looking for one little piece that I think will work in this lighting setup; I promise I won't use anything else.' Knowing Michael has such a strong visual sense, I was of course confident he wouldn't put anything in the film that didn't look great."

When the production left Alcatraz to film in San Francisco, it did not mean that the island could be forgotten altogether. Lit up like a Christmas tree, the island often shone like a beacon in the background of the city-based scenes. "A lot of times when we shot in San Francisco we had all of Alcatraz lit so you could see it clearly from town, using a half-dozen 12Ks and 100 Par cans with a couple of generators running," Schwartzman notes. "Part of the power of the story is the proximity of the threat, the fact that Alcatraz is only eight minutes by boat, just 1,500 yards and a short rocket blast away from the city. When we did the big car chase, as we panned with a car racing through an intersection, Alcatraz was right there in the frame; you felt you could reach out and touch it.

"There were nights when we would be shooting in a warehouse on a pier overlooking Alcatraz, where the movie FBI had set up its command headquarters, and we had Alcatraz completely lit up so that it was in the background in those scenes. At the same time, I had an aerial unit shooting helicopters [provided by West Coast Helicopters] flying around the prison, and it was a matter of building up and controlling the light levels so it would work for all of the units. There were plenty of nights where we had 35 to 40 electricians on the island and in different parts of the city, just to keep it all together."

Resisting the obvious temptation to shoot the entire picture on Kodak's 500 ISO 5298, Schwartzman decided to mix and match stocks best suited for the dusky look Bay sought. "I tried to stay off of 5298 as much as I could," he says. "I used mostly 5293 for interiors and 5248 for exteriors. Those three stocks are so well matched, the mixture wasn't a problem. I hear about entire pictures being shot on 93, but using tiny flashlights as your only illumination doesn't work on 93. The 48 has a little more contrast than 93, so when we had foggy San Francisco weather the 48 would give us some contrast back. I also found that exposing the 48 one-stop under looked great."

Schwartzman adds. "For the first three weeks you're just struggling to get the timer to make it right, but if I had been in town, I might have thought about flashing certain scenes, although I generally keep it straight."

However, concerns about optical process image degradation were not sufficient to dissuade Schwartzman and Bay from filming in Super 35. "We chose Super 35 mainly because Michael likes to use close-focus, wide-angle lenses," the cinematographer says. "We lived on 17.5mm and 21mm close-focus; 50 percent of the film was shot with those two lenses, mostly the 21mm. The anamorphic equivalent to the 21mm would be a 40mm, and it would not be a close-focus lens. I knew our image quality could suffer because of the optical process necessitated by Super 35, but we got an incredible scope of view. We went for deep focus, a Citizen Kane kind of look, complete with low angles and practical ceilings."

Bay had expressed some concern about the Super 35 optical printing step but was buoyed by the image quality that cameraman Darius Khondji, AFC achieved for David Fincher's Seven [see AC October 1995], another Super 35 picture that made extensive use of darkness. Notes Schwartzman, "I really like how close you can get with the 17.5mm lens, and there's nothing comparable in anamorphic. Plus, I like to do things like snap this little skateboard-wheel dolly onto the camera and use a prism to get an even lower angle, and you just can't do that with anamorphic.

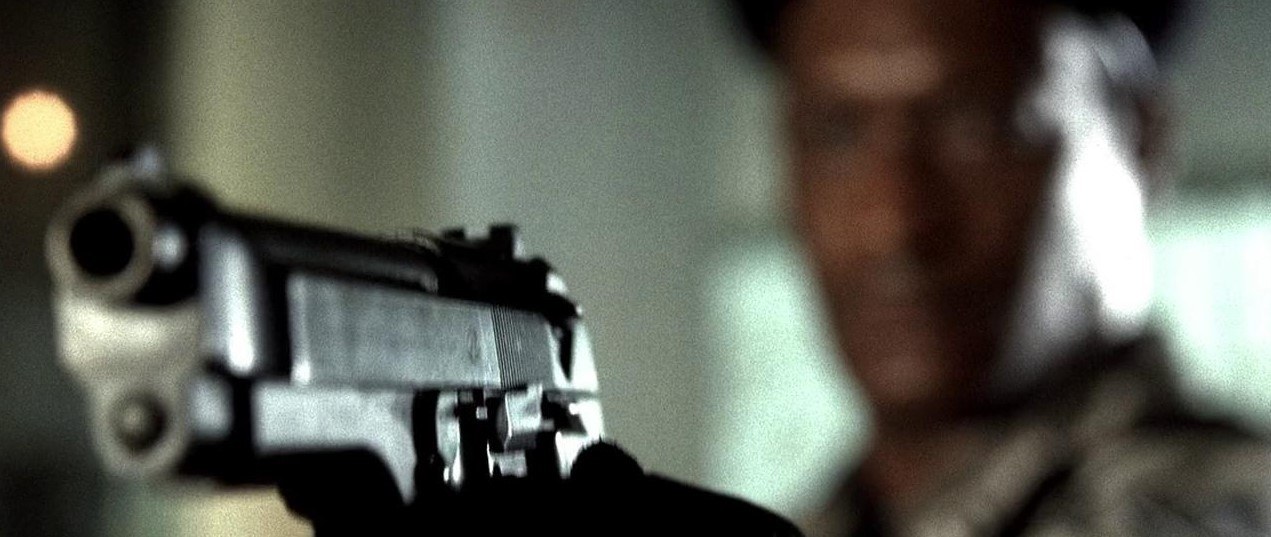

"We also used the Frazier Lens System, Panavision's new infinite depth-of-field lens, which holds focus from the lens surface to infinity. We have one shot where someone is holding a gun right up close to the camera. Normally you would have to rack-focus from the gun to the actor. But with the Frazier, it's all in focus — from the gun, which is a quarter-inch from the front lens element, to infinity."

In addition to working primarily with wide lenses, zooms were also used, albeit sparingly. "We carried a short Primo zoom and the 11:1," recalls Schwartzman. "We only used them for day exteriors, when we had to move quickly to get a good stop and to give the camera guys a little break. People can get really lazy and just set up a zoom and move back and forth. For our purposes, the short primes were great because the focal length isn't going to change; that's good for lighting. And of course, the less glass we had on the camera the better because we had a lot of small light sources, and the primes enabled us to avoid a lot of flares. We shot near a giant blast furnace and had no flare problems at all with the primes."

"Panavision says their zooms are as sharp as their primes, and I agree in the best case, but we were always in the worst case!" Schwartzman points out. "Also, we needed to stay light, because of all of our camera movements. We mostly used 200' or 400' magazines; rarely would you have seen the camera fitted with a 1,000- magazine and a zoom on the set of The Rock.”

"The camera crew did an absolutely stunning job," he attests. "The first AC, Chris Duskina, did the most incredible focus-pulling job. And we had no scratches, even though we were always in crappy locations with dust and water and 14 rats running loose. The producers allowed me to have all the manpower I needed, and to let people who were exhausted take four days off and come back, which is an ideal situation for making a movie of this size."

With the arduous shoot of The Rock now a lingering memory, both Bay and Schwartzman say they will be going back to commercials for a few months. "They're a good way to stay sharp when you're not shooting a feature," says the cinematographer.

But the director offers his own reasons for the between-features work: "I don't want to turn into some old guy who just shoots a movie once a year. I'd go crazy if I couldn't shoot every other week!"

Schwartzman was invited to join the ASC in 1997. You'll learn more about him in this ASC Close-Up profile.

He and Bay would continue their collaboration on the features Armageddon and Pearl Harbor. The cinematographer discusses their working relationship in this video shot during a Friends of the ASC event held at the Clubhouse: