The Shows Must Go On (Screen)

ASC members Ellen Kuras and Declan Quinn help bring a cinematic approach to multi-cam Broadway performance captures.

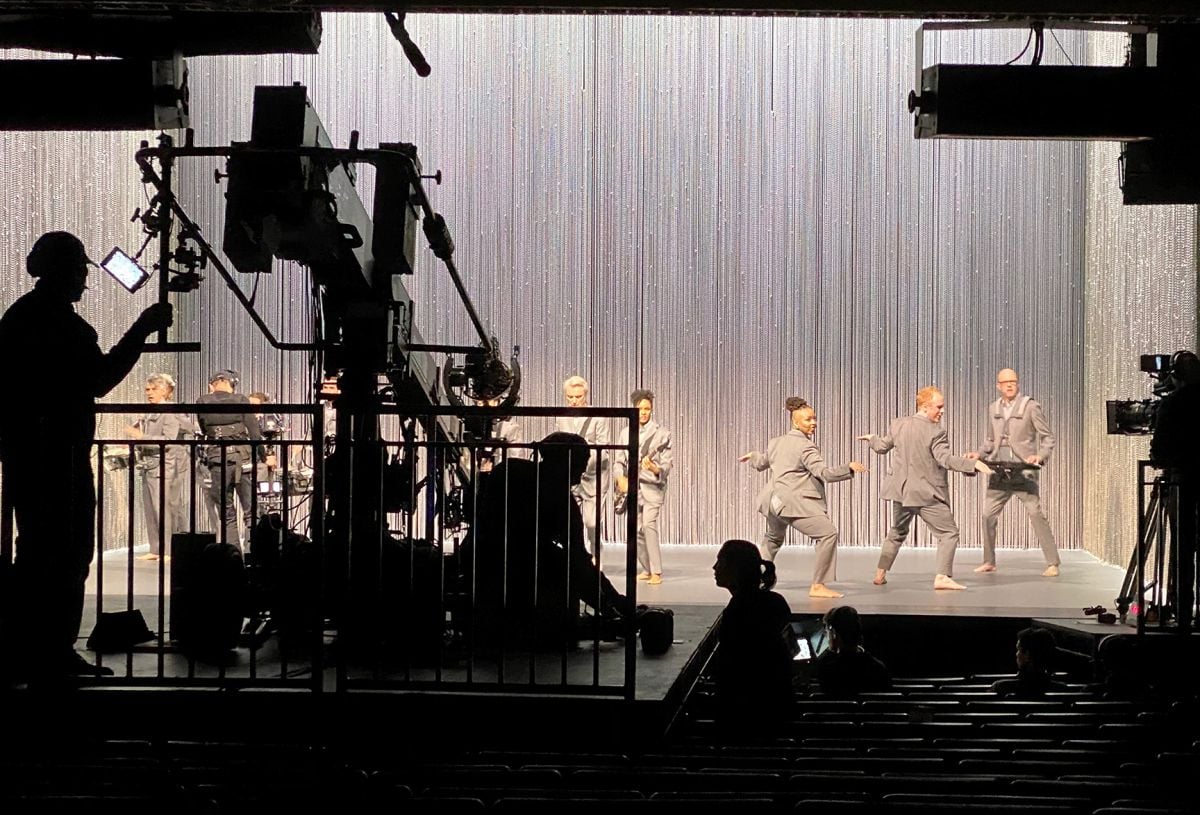

The past two years have seen a rising trend in multi-cam Broadway performance captures designed for streaming and television audiences. Leveraging large-sensor digital cinema cameras like the Sony Venice on the front end, broadcast style multi-cam interconnectivity on the back end, and cinema production techniques, these projects have truly raised the bar for what’s become known as “cinematic multi-cam.”

Producers Alec Sash and Nina Shiffman, in conjunction with production companies including Radical Media, as well as their own company, Seeker, have undertaken projects including American Utopia, Come From Away and others with an eye towards preserving these unique cultural moments in their most authoritative form. “At the time we shot American Utopia, in February, 2020, a new limited engagement for the show had just been announced. We wanted to preserve the energy and really every aspect of that show, which we thought would be gone forever. Of course, then the pandemic hit the next month,” explains Sash.

Shiffman adds, “In each of these cases, what we found when talking to directors and cinematographers — like Ellen Kuras, ASC and Declan Quinn, ASC — was that they wanted the projects to be cinematic, to be interpreted in a cinematic way – and we could do that with multiple cameras. But it wasn’t like a live broadcast of a football game: we were shotlisting and really paying attention to the coverage we could get.”

“Classic performance captures, like Martin Scorcese’s The Last Waltz, documenting The Band’s final performance, and Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense with Talking Heads, had come out in the beginning of my career and were big influences on me as to what live capture could be, even then.”

— Declan Quinn, ASC

For David Byrne’s sprawling, sanguine cultural epic American Utopia, directed by Spike Lee and shot by Kuras, 11 Sony Venice cameras, supplied by AbelCine’s New York location, were utilized. The cinematographer had first used the Venice on Pretend It’s a City, a Netflix series featuring conversations between humorist and raconteur Fran Lebowitz and director Martin Scorsese. “I knew that I wanted to find a camera that was filmic, cinematic, but I also didn’t want it to be too noticeable on the streets of New York,” Kuras describes. “I was talking with my camera assistant Rick Gioia and we ended up having a long conversation about it. I really liked the personality of the Venice. It’s similar to the way I look at families of lenses; they’re like people and they each have personalities, you know?”

Key 1st AC Rick Gioia and 2nd AC Jordan Levie (who now also works as a first) have served together on many of these recent projects with different directors and DPs. “The Venice is in the sweet spot for this kind of production,” Gioia says. “The sensor size and recording modes worked to our advantage to allow us to use a broader range of lenses and still maintain 4K resolution when shooting in its Super 35 mode, to maximize speed and focal length range.” 2nd AC Jordan Levie adds, “The broadcast guys love the Venice because it uses all the normal protocols as well as having a LAN port. They were very comfortable with it fitting into the backend stuff.”

“We typically shot at between T4-T8,” Gioia continues. “We called that range our ‘dream stop’ because it allowed for some of the slower lenses, while still maintaining good depth of field. The beauty of the Venice is that you can always bump up the ISO with a negligible downside.”

Adds Levie, “The dual ISO allowed us to shoot at 2500, even 3200, which was a huge help, otherwise Declan and Ellen might not have been able to embrace the darker parts of these shows.”

Quinn was the director of photography on the filmed versions of Hamilton and the upcoming Jersey Boys Live! (with lighting designed by Howell Binkley) as well as Diana: The Musical (lighting designed by Natasha Katz), and many other theater-based projects stretching back decades. He revealed a close collaboration with each show’s theatrical lighting designer (or LD): “The whole thing is about preserving the lighting designer’s show, not changing it,” says Quinn. “We didn’t want to see our lighting at all. For overall frontal fill, we’ll often utilize the theater’s entire balcony rail, alternating Lekos and PARs focused across the whole acting plane on stage. This also put catch lights in the performers’ eyes which was helpful for us. A show’s lighting is often very contrasty, so when a performer is in deep shadow you need something so we can see what’s going on in the eyes, especially when going in close. It’s very important for me to get that glint in the eyes.”

A key part of prep is stepping through the lighting designer’s cues to see where supplemental lighting may be needed to enhance certain sequences or musical numbers. “We call it ‘cue-to-cue,’” says Levie. “That’s where, during prep, a DP like Ellen or Declan will sit with the show’s LD and go through literally cue-by-cue to see exactly what it looks like to a live audience and then understanding how we need it to look for our cameras. It’s very meticulous and time-consuming, so they’ll take sometimes 3, 4 or 5 days if possible.”

Gioia adds, “Sometimes these lighting cues have been set, for a long-running show, for literally years and for the most part it doesn’t change, or maybe evolves very slowly. And now these vagabonds [the film crew] come in, and we want to add lights. It’s a delicate thing… you have to respect the LD, obviously, because it’s their show.”

Kuras concurs: “I really wanted to honor the original lighting because it was fantastic. What Rob [American Utopia lighting designer Rob Sinclair] had put into place was amazing. I was making adjustments for reasons of filming it, which I had done before in a theater setting on a number of concert films, like Berlin, with Lou Reed, and Neil Young’s Heart of Gold, with Jonathan Demme.”

Each show is photographed over the course of roughly 3 to 6 days, and may employ as many as a dozen of complete camera packages, most with their own dedicated operators and ACs. Additional cameras are locked off on wide shots of the theater’s proscenium and audience. The front end of the schedule usually involves shooting the entire show live. Gioia explains: “Usually, the layout is that we’ll do two or three full performances from beginning to end with the full cast and an audience. Those runs will cover all of the main angles that don’t involve a crane or Steadicam. All of that’s done without interruption in real time. Once those are in the can, we’ll go back and pick out individual musical numbers to shoot on subsequent days what we call ‘specialty coverage.’”

On these days, specific musical numbers or sequences are slated for more traditional filmmaking techniques involving Steadicam, close-ups, and moving camera shots using cranes or jib arms. These specialty days are filmed without an audience, to allow for multiple takes and to assess coverage.

Both Quinn and Kuras have also utilized cameras mounted in the theaters’ overhead fly system (similar to the “perms” in a studio environment), looking straight down on the stage. “We call them the ‘Busby Berkeley’ angle,” Gioia says. “They’re really fun shots — for example, on American Utopia, we had these squares on stage lighting up and curtains made of chain mail that made for a very austere, designed, ‘Talking Heads’ aesthetic.”

Interestingly, these shots could be executed during the live performance runs since the camera and other rigging were up high, hidden by proscenium curtaining. “We rigged the camera perfectly nodal, in the center, pointing straight down,” says Gioia. “That was its own challenge since there was a very dense nest of lights up there.”

Levie adds, “We built the camera in the center of the stage and had the theatrical grips [called ‘flymen’ in the theater world] yank it up there using chain hoists; camera rotation was driven by a lazy susan.”

Quinn also employed a straight-down angle suspended using his trademark high-test latex tubing technique, which he has used for years (notably with director Mike Figgis on Leaving Las Vegas) and has demonstrated in past ASC Master Classes. “A very a long piece of elastic distributes the weight of the camera over, say, 40 feet [when rigged to the perms in a studio scenario], he explains. “Depending on the weight, you as the operator can easily stretch it another 6, 8, 10 feet. In addition to smoothing out any camera shake, it also allows you to operate on a long take without getting shaky or tired.”

All involved spoke of the thought and consideration that goes into choosing operators. “Most operators are pretty well-rounded, but some are just deadly at certain shots,” says Gioia. “Lyn Noland, for example, always gets the ‘Howitzer’ [an Angenieux 24-290mm T2.8 zoom] and is usually rear of the house shooting straight on. She’s always in there grabbing these amazing shots along with her focus puller. So there’s a lot of nuance, thinking and care that goes into pairing operators with ACs.”

Alec Sash: “The operators that we use on these shows are not only hand-picked, but they’re from a very curated list. Beyond Steadicam, there are also people who are really good on a long lens, really good at handheld, or really good on a dolly. The DPs we work with are aware of who everyone is and what their experience and strengths are. This is all to say that the operators very much contribute to the show; they’re almost like additional performers.”

For the days where live performances are being shot, with up to a dozen cameras being utilized, camera department headcount could stretch to as many as 20-30 people. Add to that the show’s existing theatrical crew, as well as VTR/playback, and technical crew from the broadcast world (including engineering personnel from AbelCine, who have supported many of these shows), and total crew headcount can easily swell into the hundreds.

Technical manager and systems engineer Brett Dicus, of the NY-based production management company TV Tech, believes in the power of visual diagrams to illustrate everything from camera drops to lighting and monitoring signal flow, to seating charts mapped to six-foot distances during the time of COVID-19 restrictions. Using Vectorworks software, Dicus documented camera department “places,” as well as providing the coordination necessary to manage equipment logistics and, crucially, monitoring (among a host of other details) – all during an era of pandemic-related restrictions.

“It’s interesting to contrast the experience we had on American Utopia, which was filmed pre-pandemic, and [the forthcoming] Jersey Boys Live!, which was shot during the time of COVID restrictions. Over the last couple of years, my role shifted from having to support a single video village to now needing to provide, in essence, a customized video village for each of 30 desks, all with intercoms, spread out over a huge area in these theaters,” says Dicus. “It’s important that everyone is seeing what they need to see in order to do their job.”

“I think my documentary background informs everything I do, as both a DP and a director — dramatic features as well as music films like American Utopia.”

— Ellen Kuras, ASC

Key to the monitoring workflow was the “multi-viewer,” a ganged view of all cameras running during the performance, available to all stakeholders along with solo’d views of each camera.

Dicus explains, “We resolved a lot of the issues introduced by COVID-related restrictions by putting the multi-viewer in the video router and making it available to everyone so they could see at a glance what each camera was doing and then essentially punch in on an individual camera if they either saw something interesting or needed to give a note.”

The multi-view was also recorded as an ISO for editorial to use as reference, to see where the best shot was for a given performance moment at a given time. Playback timecode was overlaid with each camera’s time of day timecode, as well as the title of the current song being performed, to aid in camera and shot selection.

“I think one of the biggest takeaways from this intersection of Broadway and COVID in the past two years is having the multi-viewer going to post as well as being used on set to review footage. I think a lot of people have appreciated just having everything in one multi-viewer, as a single container that could be handed off at the end of the day,” says Dicus.

One reason, Dicus says, that the Venice fit into these productions so well is because it features multiple 12G SDI outputs, which each allow for a 4K video signal at up to 60 fps to be fed from the camera via a single cable, thanks to a fiber “back” from MultiDyne Systems, which were used to aggregate all of the cabling from a given camera into a single long, flexible fiber-optic line. Each camera fed back to the broadcast switching and monitoring infrastructure, however primary recording still took place in each camera, typically in Sony’s X-OCN RAW format.

For the specialty shooting days, where fewer cameras were in play, or for wireless Steadicam rigs where more freedom of movement was required, a combination of cameras with and without fiber backs were used. Special “throwdown” took camera signals from copper wiring to fiber at some point. “So, like the 50 feet from the cameras to the stage-left edge would be copper and then it would be converted to fiber, in a rack, to feed back to our video engineering core, which was set up elsewhere in the theater,” says Dicus.

“My work as a tech manager is a lot of gluing the dots together with all the different departments and understanding the implications when it comes to the engineering of whatever we’re doing. Apart from the complexities of, say, mixing fiber and copper or collaborating on a solution with AbelCine’s technical staff for remotely pulling iris, so much of it comes down to coordination and communication. A well-set-up video village, or even a seating plot, can be as important to a successful shoot day as the most esoteric technical minutiae. It all has to work together.”

These documents were essential to bringing together a crew drawn from the distinct worlds of filmmaking, theater, and broadcasting. “The documents and drawings are instantly recognizable by everyone regardless of their background,” says Dicus.

The traction gained by these early successes has already borne fruit in the realm of streaming distribution, especially during the pandemic era. This exciting, re-imagined genre has brought the best of Broadway to millions. AC Rick Goia says: “I think this format has become established; there’s a market now. As well, it’s kind of democratized access to top-tier Broadway musicals, so you don’t have to necessarily be in New York, and you don’t have to pay thousands for a seat. That’s still going to be a great thing post-COVID.”

Producer Alec Sash: “Theater has such a strong history and identity. But there’s also a new generation that’s coming out of school now, theater writers and filmmakers, who kind of grew up on this ‘digital life’ and may be conceptualizing a piece of theater, and a film, as sort of one thing. We love to work with smart, talented, creative, passionate people but we’ve also been big music lovers our whole lives. At Seeker, we’ve tried to create a space for artists to constantly be relevant, be able to reach their fans, and do things that are more advanced than some of the work that came before.”

As nice as it is to see a new market validated, there will always be a need for a cinematographer’s eye to interpret the creative spark, in translating a performance to the screen. Declan Quinn reflects: “Classic performance captures, like Martin Scorcese’s The Last Waltz, documenting The Band’s final performance, and Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense with Talking Heads, had come out in the beginning of my career and were big influences on me as to what live capture could be, even then. On some level, I’m still striving for results like that, while keeping pace with cultural trends. The thing to remember, though, for anybody out there doing captures, is that you can’t say, ‘Oh, let’s do a capture in two weeks; we’ll just throw 10 cameras at it.’ Even if you’re going to fully embrace the show’s lighting, you’re always going to need some amount of supplemental, and plenty of time for prep.”

ASC Lifetime Achievement Award-winner Ellen Kuras opines, “I think my documentary background informs everything I do, as both a DP and a director — dramatic features as well as music films like American Utopia. I’ve learned to think quickly, when I walk into a space, to just start sizing it up and thinking about, you know, where do I want to be with the camera? What story do I want to tell? I’m always thinking about what I’m going to use, what I’m going to cut to. It’s really important because it will determine what coverage you need to get. I mean, I’m not going to cover every side of everything – that’s crazy. You’ll never make your day.”

Smith is a camera technology specialist at AbelCine in Brooklyn, New York.