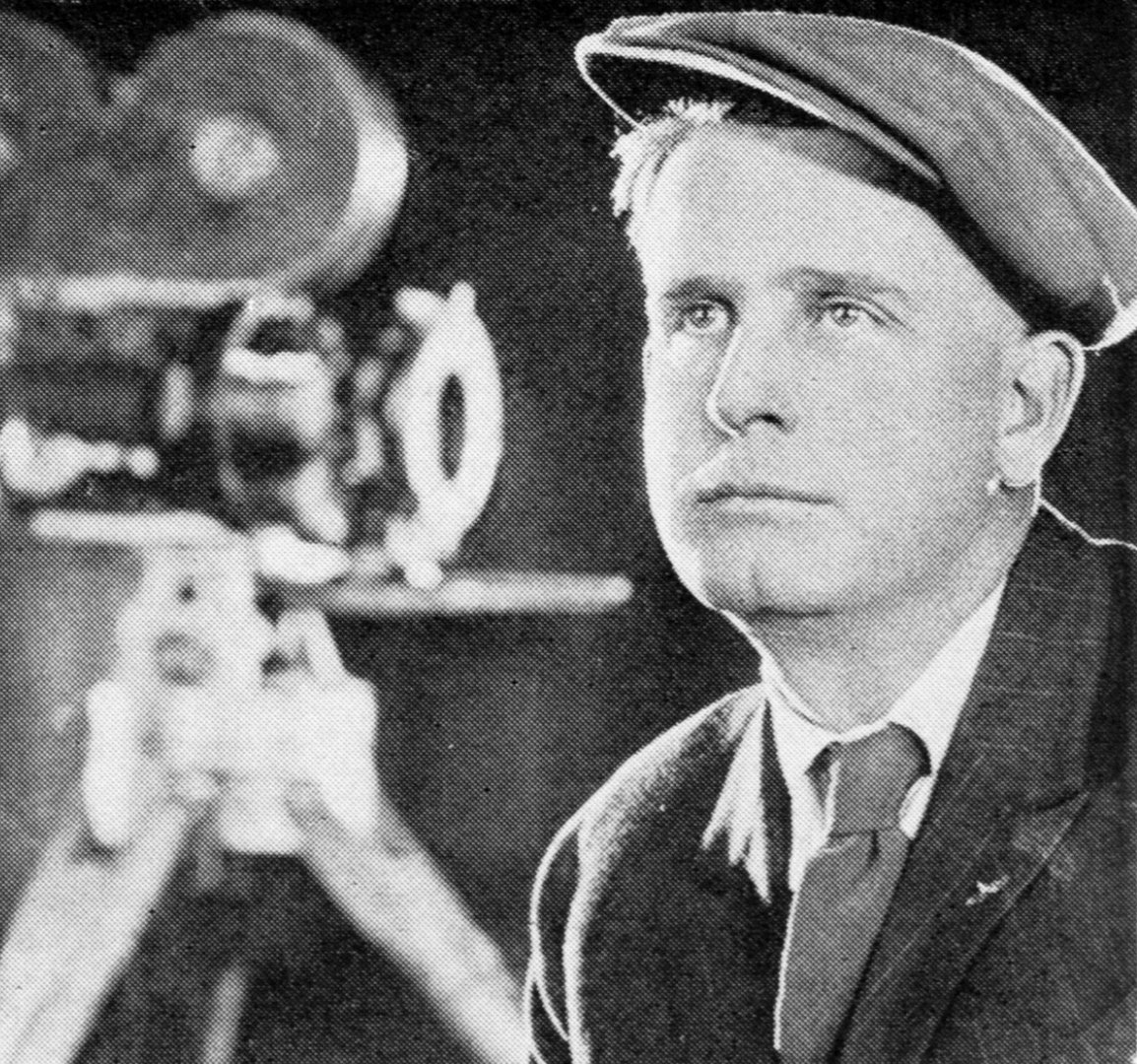

The Special-Effects Cinematographer

“Contrary to the general impression, the studio special-effects cinematographer must be decidedly more than merely an engaging young person with a pleasant smile and a knack of doing strange things with a motion-picture camera.”

This article was originally published in AC, Oct. 1932. The text is presented as originally printed. Some images are additional or alternate.

Contrary to the general impression, the studio special-effects cinematographer must be decidedly more than merely an engaging young person with a pleasant smile and a knack of doing strange things with a motion-picture camera. Of course, he must be an expert in one or more of the many special photographic processes used for “trick” work; but in addition to being intimately familiar with all phases of photography, the trick-worker — especially the individual in charge of a large studio’s trick department — must be a champion kibitzer. He must be thoroughly familiar with the technique and personnel of every other phase and department of production. No, it is not his task to show them how to do their own work — but only through intimate knowledge of the methods and aims of the other departments can the special-effects man make his department as useful to the other branches of production as it can be.

As a rule, the less technical departments of production — the writers, directors and cutters, not to mention, of course, the production executives — take one of two viewpoints in their relations with the trick department; either they ignore its possibilities completely, or they feel that nothing is too impossible for it to achieve. It is, therefore, up to the man in charge of the special-effects staff to wage a constant campaign of education as to the services and possibilities of special-effects work. It should extend to every individual or department of production which could possibly benefit from the assistance of the special-effects department.

“At least one major studio has adopted a policy of maintaining a special reel of process shots from current productions, illustrating the possibilities of the various processes, and which is constantly available for exhibition to the studio’s writers and directors. This is a fine policy.”

The writers, for instance, frequently hesitate to include in their scripts scenes or effects which, though easily possible through the aid of the special-effects department, would be either prohibitively expensive or dangerous if attempted in the normal manner. Since the advent of talking pictures, it is possible for writers to build up their stories through the use of dialogue in places or under conditions where recording would be impossible without the aid of the trick department. Certain optical effects, too, which are useful in telling a story can only be conceived if the ability of the special-effects department to execute them is known beforehand. It is therefore vitally important to familiarize the writing staff of a studio with the possibilities of special-effect processes, and to constantly remind them of these possibilities, so that they will simply proceed to turn out the best scripts possible, and leave the rest to the ingenuity of the special-effects staff. At least one major studio has adopted a policy of maintaining a special reel of process shots from current productions, illustrating the possibilities of the various processes, and which is constantly available for exhibition to the studio’s writers and directors. This is a fine policy, and one which should pay big returns in production efficiency.

The next link, of course, is the director. Or, to be more accurate, the directors, for a special-effects department is as a rule constantly working on scenes from half a dozen or more productions. It is imperative that the process staff thoroughly understand the different ways in which each of these directors works, for this will in many cases determine the treatment to be given the process shots for a production. Some directors, for instance, go in for highly pictorial effects; others, for modernistic effects of angles, montage, etc.; while still others depend entirely upon the swift pace of their action, and prefer extremely simple, commercial photography. Each of these will naturally make entirely different demands for process scenes.

The cinematographers, too, are predominantly individualists; the artistic style and technique of no two men is ever exactly the same. The process worker must take this into consideration in planning his work, in order that the process scene may be a perfect photographic match for the rest of the picture. Unless a process scene matches the rest of the picture perfectly, carrying the same type of lighting, diffusion and general photographic quality, it is sure to stand out as a process shot in the minds of the rapidly growing multitude of amateur cinematographers, who study each picture as they would a textbook. To the uninformed layman, it will stand out as an intangible irritation, though he may not know what it is that bothers him. The special effects staff must work in especially close coordination with the production cameramen, for different types of treatment in the regular production shots may require entirely different types of treatment for the process scenes — in some cases, even the use of different processes to gain the same effects under different conditions

The production of the process shots themselves is more or less a matter of routine. It has been discussed in these pages so frequently that further repetition at this time is unnecessary. There is, however, one phase of the problem which has seldom, if ever, been mentioned in print; this is the matter of costs and estimates. Under the existing conditions in the motion picture industry, rigorous economies in all production expenses are mandatory. Miniature and process scenes are used primarily to save money in production costs, and to add production value without proportionate increases in cost; but this work can very easily absorb an entirely disproportionate amount of money unless the greatest care is exercised. I have known of instances where a miniature actually proved more costly than a full-sized set would have been. It is entirely wrong to believe that simply because a miniature is small it is cheap. Quite the reverse! The building of miniatures requires the employment of highly skilled designers and workmen, and, unless the work is properly supervised, the costs of a miniature can be run up to very sizeable figures.

“Marine miniatures, naturally, form an entire specialized subject in themselves, as do floods, explosions, and wrecks; in fact, every miniature is an individual problem in itself.”

The greatest of care must naturally be used in planning miniatures. Their design and construction demands years of specialized experience, for a motion picture miniature is something basically different from either a toy or a conventional display model. It is a true scale model — but with all irrelevant detail suppressed. Suppose, for instance, we are to build a miniature ship. We would not build it as we would a regular display model, which is to be placed in a show window for everyone to admire. If you visualize a ship at sea, far enough away so that the width of your field of vision is twice the length of the boat, you will get only the essentials; if the ship is a steamer, you would notice the number of funnels, and differentiate as to whether the craft were a warship, a liner, a yacht or a tramp. If it were a sailing ship, you would be conscious of the number of masts and, roughly, of the rig — but you would not be conscious of every detail; every rope and pulley, every stay and stanchion. If you build a reduced-scale reproduction of what you have just visualized, you would not have any sort of a display model, but you would have an excellent motion-picture miniature.

It is the same with architectural miniatures. Irrelevant detail must be suppressed. A miniature which, to the eye, seems a perfect reproducion of a building or group of buildings, would be very likely to show up on the screen as a most obvious miniature. Let us suppose, for instance, that we are to build a miniature of New York’s Broadway. If we build it with photographic accuracy and detail, no power on earth can make it look like anything but a miniature on the screen. If, however, we build only the salient details — the contour of the buildings, the course of the streetcar tracks, a few dim shapes of automobiles, trams, etc., leaving the rest to the imagination, we would have a satisfactory miniature. Since we have left out a great deal of the detail, such a miniature would be far cheaper to build, as well as more satisfactory than a detailed model.

The most satisfactory method of building these architectural miniatures is to use relatively crude plaster casts, with only the most meagre detail. If you build them out of wood, you find that it is practically impossible to eliminate the sharp lines on corners, etc., so that regardless of lighting, diffusion, or anything else that can be done with the camera, they will still stand out as obvious miniatures. In addition, they are more expensive than the simpler plaster casts.

The relation between the scale of the miniature and the speed of the camera is important — and intricate. It cannot be summed up in any arbitrary rule, but must come as the result of experience and observation, which develop an intangible photographic sense. The scale used for miniatures usually varies between 1/8 inch to the foot and 4 inches to the foot; camera speeds may range from stop motion up to eight times normal. It would seem relatively simple to calculate the scale and speed of miniatures, but another variable is introduced by the question of the focal length of the lens or lenses to be used. In photographing a certain large miniature recently, we built the set to a scale of 1/2 inch to the foot; with 18 cameras used to photograph the scene from different angles, the use of as many different lenses of foci ranging from 32mm to 6 inches, the camera speeds varied between three times normal and eight times normal. Naturally, too, different types of miniature scenes require different treatment; a ratio of scale, speed and lenses that would suit, for instance, an earthquake, would be utterly wrong if used for a flood. A ratio suited to a simple earthquake would likewise be entirely unsuitable for use if the earthquake were followed by explosions. Marine miniatures, naturally, form an entire specialized subject in themselves, as do floods, explosions, and wrecks; in fact, every miniature is an individual problem in itself.

One of the most useful departments in a special-effects studio is the one which is devoted to optical printing. This is really the jack-of-all-trades of special-effects work. All fades and lap-dissolves are now made by optical printing, of course, as are the infinitely varying optical “wipes” now being so frequently used. But, more than this, the optical printer is often drafted to insert special effects not in any other way obtainable, or to salvage both production and trick shots which might otherwise have to be discarded. In a recent Joe E. Brown production, for instance, the script required the star to smoke cigars almost incessantly, and to blow smoke rings. Now, Brown does not smoke at all — and of course he doesn’t blow smoke rings. Therefore, the optical printer was called upon to supply both the smoke and the smoke rings.

“Cameras which have proven themselves perfectly satisfactory for production work have been rejected for use in special-effects work because of insufficient accuracy in their mechanical functioning.”

In an article in the Cinematographic Annual, Volume II, Lloyd Knechtel referred to a miniature train wreck in which two different takes were combined with full-scale scenes, and in which the wreck was artificially sped up — all by means of the optical printer. In a recent film of our own, the optical printer was called upon to save some expensive retakes when it was found that one of the principal roles had been badly miscast. As it happened, during a long sequence played by practically the full cast of the picture, and upon a large and expensive set, this particular player was seated in a chair. It was, therefore, no surpassingly difficult matter to re-take the scene showing only the new player, seated in the chair, and then to combine the two takes into a single scene by means of the optical printer — thereby saving some expensive retakes. Similarly, one of my friends in another studio used an optical printer to repair a split-screen sequence in a picture in which the star played a dual role. In making the second half of this sequence, the camera was racked over too far after focusing, so that there was a considerable gap between the two halves of the take. Thanks to the optical printer, this was moved over to where it belonged, and blended with the other half of the picture, saving the company a large sum, and some intricate retakes.

A successful special-effects department should whenever possible maintain its own laboratory. Despite the perfection of the modern production laboratory, it is not fitted to handle the work of a special-effects department, which uses many different types of film — Panchromatic, Super-Sensitive, Orthochromatic, Positive, Master-Positive, and Duplicating Stock — and in which each individual scene requires individual treatment in the laboratory. Therefore, the only solution is for the special-effects department to maintain its own laboratory; a miniature plant, as perfectly equipped and staffed as the best production laboratory, but, naturally, with a far smaller capacity, and closer control of all operations.

As an inevitable consequence of all this, there is a highly important question of equipment maintenance to be remembered. The abnormally high operating speeds of special effects cameras, and the fact that for special-effects work the camera must be constantly maintained in perfect operating condition, make this problem of maintenance a grave one. Special-effects cameras must, also, be considered as the highest type of precision machinery, for in many instances, cameras which have proven themselves perfectly satisfactory for production work have been rejected for use in special-effects work because of insufficient accuracy in their mechanical functioning.

The special-effects cinematographer must, therefore, be like Kipling’s marine — “a sort of a blooming cosmopolouse.” [From the. poem "Soldier an' Sailor Too", Stanza 2 (1896).] He must be a technician of a high order, an artist, and fully informed regarding the work and the personnel of every other department in the studio. Most of all, he must be enough of an executive to successfully coordinate the work of his department with the schedules of perhaps a dozen production units — and enough of a diplomat to work efficiently and amicably with the dozen different directors, writers, cinematographers and supervisors connected with those units. As a rule, he is all of these things; he wouldn’t survive if he were not — and, like the marine, “you could put ’im ashore on a bald man’s ’ead to paddle ’is own canoe.”

At the time, Jackman was the Director of Scientific Research at Warner Bros.