The Story Behind the Filming of Young Frankenstein

Far-out special effects and glorious black-and-white photography help revive a famous monster for Mel Brooks’ zany satire.

Young Frankenstein incorporated more photographic and special effects than any other film I've ever worked on. The range was tremendous, from trick candle effects to 500,000-volt electrical discharges, from low-hanging fog to torrential rain. Chases, explosions, and fire of past films seemed like child's play by comparison.

One of the most difficult times of a new production, for me, is that time prior to the first set-up. It's during this time that I must make commitments to the art director regarding my requirements in getting the kind of look that I feel the film should have. Also, during this same period, meetings with special effects, scenic artists, wardrobe and, in this film, make-up are of great importance; they all require a commitment. Of special consideration in approaching this film was the film laboratory, which had not processed a black-and-white film in over six years! But, beyond all the above, and of greatest importance, was my prime consideration: what was I going to do to make this film have a "special" look and also be one that would be right for the story? Looking back, now that it's all finished, this is my story of the creation of the film, Young Frankenstein.

A very dear friend of mine often quotes: "Things happen for a reason; don't be upset about what has just occurred." How very true, I had just turned down a film about which I had bad vibrations, and there was no other job to turn to. I learned "the reason" the next day when I was called to have an interview with Mel Brooks, the director of Young Frankenstein. How does a director interview a cameraman? Does he ask, "What stop do you usually shoot at?" Mr. Brooks knew of my screen credits, but he didn't know if we'd get along as people.

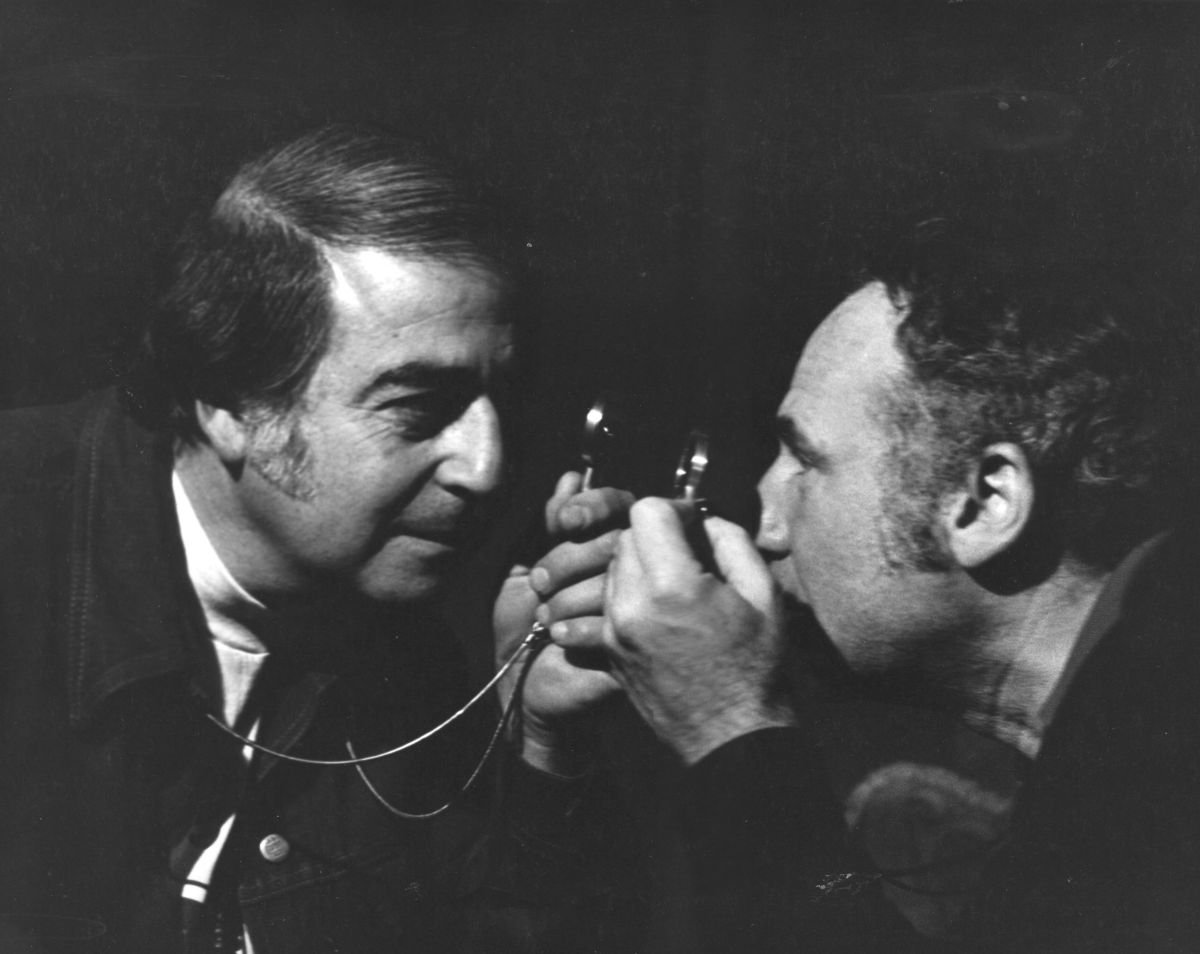

The relationship between a director and his cameraman is a very close one, and we had to be sure that we'd get along. At the time that a director interviews a cameraman, the cameraman, if he cares, interviews the director — hopefully unbeknownst to him. Mel began kidding me about some of my past films and so-called “errors” he felt I'd made. He asked me if I didn't think that, in Diary of a Mad Housewife the white tub in the bathroom was too bright, and didn't the gels on the bedroom windows shimmer a bit in a breeze? At first, I took him seriously and was more than a little upset, until I realized he was doing his "thing" and pulling my leg because there was no tub and the bedroom was an interior set that didn't require window gels. So, I pulled his leg and said, "One more derogatory remark about my work and I'll leave." We understood each other and laughed; it was the beginning of what turned out to be a great work experience.

“At first, I balked at the decision to do the film in black-and-white... But the director was firm and I soon realized, as I progressed more into the feeling of the film, that he was 100% correct.”

— Gerald Hirschfeld, ASC

At first, I balked at the decision to do the film in black-and-white; suggesting that perhaps we start in black-and-white, as the film opens in old-time Transylvania, and then segue into color as we go to modern-day Baltimore to meet young Dr. Frankenstein. But the director was firm and I soon realized, as I progressed more into the feeling of the film, that he was 100% correct.

I started my career making black-and-white films, and moved right along with the industry as color became the new medium. I'm sure you recall that television started in black-and-white and progressed technologically to color. Now, we are, in a sense, all victims of advertising and, at present, reject the use of black-and-white films as archaic. But wherein the "book of rules" does it say, "Make all motion pictures in color"? If it was correct, as it was many years ago, to use a "soft focus" lens for a close-up, we don't arbitrarily throw that out in favor of one so critically sharp, as the new lenses are, that the skin pores will show; we add diffusion to once again soften the lens. Similarly, if it's right for a story to be photographed in black-and-white we shouldn't arbitrarily shoot it in color. I found, after viewing a few days of dailies, that the black-and-white not only seemed right, but it actually enhanced the feeling and mood of Young Frankenstein.

The premise of the film was one of satire, and all components complemented that aim. The entire cast was caught up with the spirit of satirical humor and added their thing to an original and extremely humorous script by Gene Wilder (Dr. Frankenstein) and Mel Brooks. I viewed dusted-off prints of the original Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, not to copy, but to satirize. I thought of the assortment of filters I hadn't used in about eight years since my last black-and-white film, only to learn that we had no day exterior shots which would require filters. I was about to learn a new type of photography which had nothing to do with mood, or with composition, or with lighting, or sets; it had to do with photographing a "joke." The "joke" was the whole purpose of setting up a scene, and if that didn't come across there was no payoff, but more about that a bit later.

The first thing I felt obliged to settle was the manner in which the black-and white-negative would be processed. In creating a style for Young Frankenstein, I decided that my satire on the 1931 look would be based on over-emphasizing the back-lights that were the style in those days, and to really do a black-and-white film—that is, keep the middle tones to a minimum; in other words, high contrast. I was able to draw upon past experience from the last black-and-white film that I photographed, The Incident [1967]. I requested that the exposure test be processed at varying gammas from .65 to .85.

The effect of forced development of [Eastman] DoubleX Negative 5222 gives an effective film speed increase of from one to two stops and also greatly increases the visual contrast; conversely, forced processing of [Eastman] Color Negative 5254 reduces the color saturation, or contrast, in direct proportion to the increase in film speed. I settled on a gamma of .80, which more than doubled the film speed to approximately ASA 500. This extra film sensitivity was put to good use in filming the dark gray, 35' high walls of the castle sets. At an average stop of T/4, I required a minimum of lighting equipment; to be exact, 40 foot-candles more than sufficed. About a week after we began filming, the lab and I settled on a printer light of 21, almost the mid-point on a range of 50 printer lights; we stuck to it throughout the production. The director thought we were getting "timed" prints, when, in reality, everything printed on one light. That's a fairly consistent relationship between cameraman and film lab.

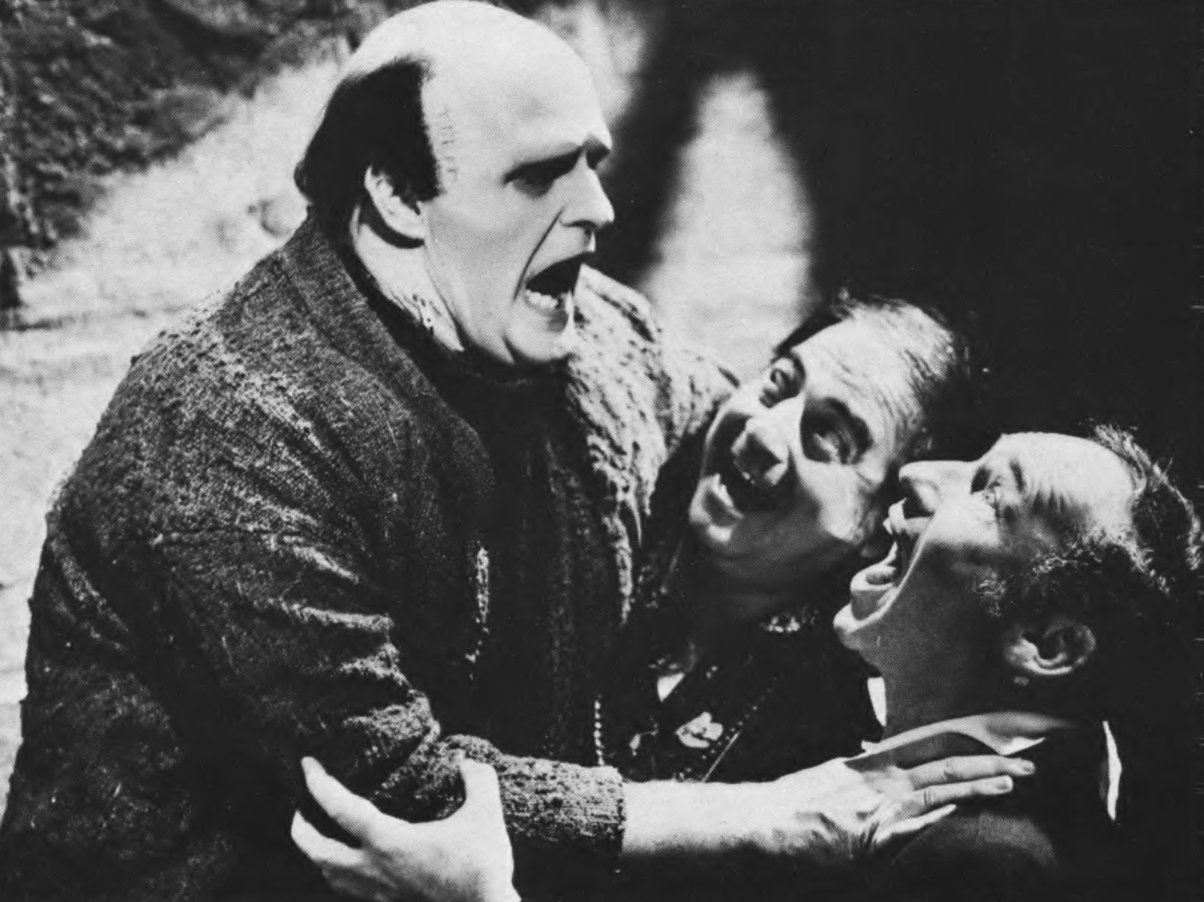

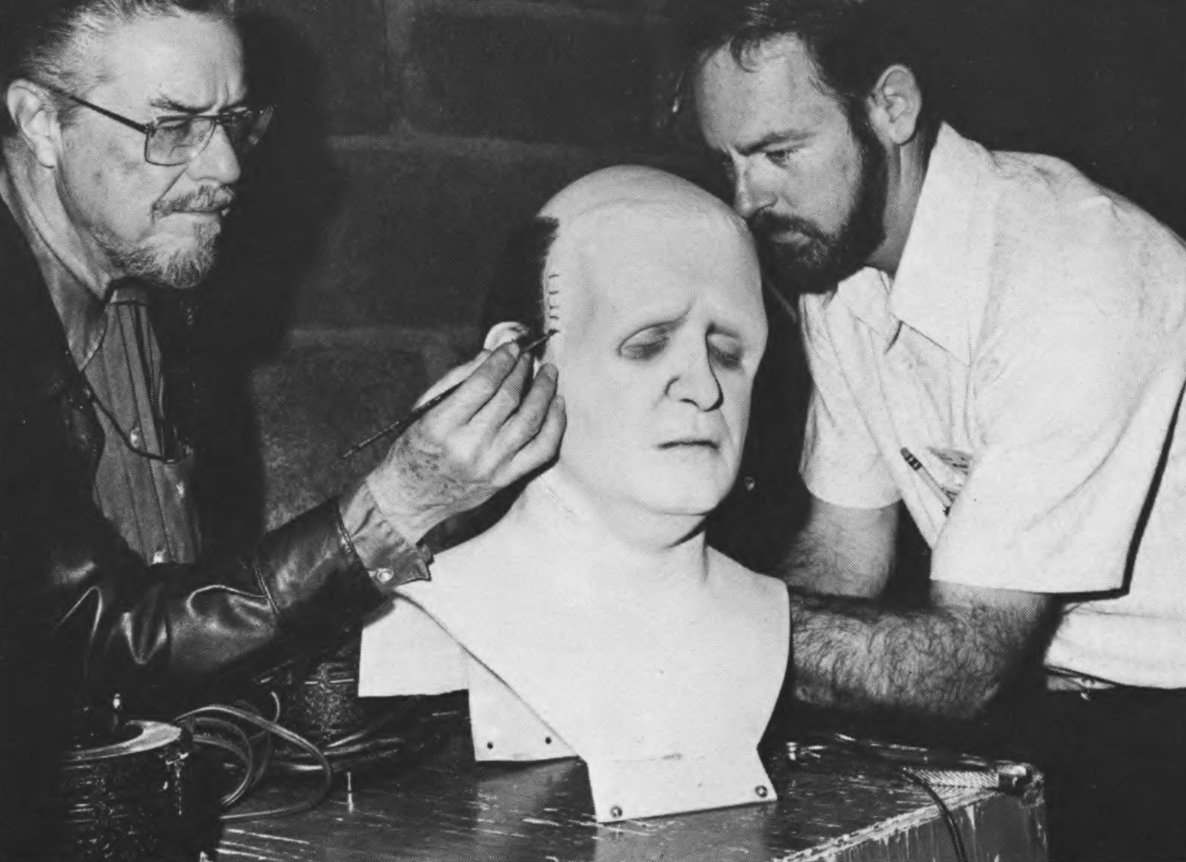

During pre-production, I worked closely with William Tuttle, our makeup creator and designer of monsters, cadavers, mummies, and decomposed bodies. In order to give the monster that Dr. Frankenstein creates a different look, Bill designed a green make-up. The green color, in black-and-white, gave the skin a "dead" look; it worked fine. However, my problem was that the film was more sensitive to that green color than to normal flesh tones. The monster always required a lower-intensity key light to bring him into balance with the other players, or he had to be netted down by a moving net guided by the key-grip. Since all good monsters have larger than normal frontal lobes, ours was no exception. In order to bring out the protuberances and throw the eyes into mysterious shadows, the monster's key light was kept very high, often hanging from the ceiling — not too easy to do, but the look was right.

In the script, the monster is exposed to a 500,000-volt electrical discharge. Peter Boyle, who played the monster, was not about to lie still for that. Bill Tuttle made a fiberglass cast of Peter's face and shoulders and that's what was used as a realistic dummy. To render the creation of life more weird Bill enclosed within the fiberglass casting some secret ingredients that resembled brains, skull, and teeth and when the self-contained lights within the skull were pulsed by working a dimmer control up and down, the madness of the creator, Frankenstein, became more visually exciting.

Tuttle further contributed to the look of the weirdos that lived in Frankenstein Castle by giving Frau Blucher, the castle warden played by Cloris Leachman, dark brown lip liner and a large removable chin mole. He also created an aged and bearded "blindman" from youthful Gene Hackman. Kenneth Mars became the characterized Inspector Kemp with a wooden arm and an eye patch with a magnetized monocle! For one sequence of the film, as Dr. Frankenstein and his beautiful, blonde, buxom assistant, Inga (played by Teri Garr), discover a secret passageway, they pass through an anteroom of the secret laboratory that displays four skulls. These skulls are marked: "One Year Dead," "Six Months Dead," "Two Months Dead" and "Freshly Dead". Tuttle carefully designed out of plaster, fiberglass, wax, false teeth and monkey hair, replicas of all the above in realistic stages of decay— all but one; the one marked "Freshly Dead" was our English comic Marty Feldman, who most humorously played Igor, the assistant with the changeable and vanishing "humpback."

The castle sets of Young Frankenstein were something else again. Dale Hennesy, the production designer, created an almost unbelievable complex of castle courtyards, reception hall, winding open spiral staircases, secret passageways, bedrooms with secret rotating panels, and a laboratory with an operating platform that was hauled through the roof by steel chains onto an exquisite exterior roof set surrounded by a stormy, cloudy sky backdrop. The task for Dale was a labor of love, and $400,000 later there were the most magnificent 35'-high sets, cobbled streets, and assembled rooms of a type that would make any cinematographer's mouth water. Dale had these rooms decorated in varying degrees of grey stone, which I then could reproduce in any tone, depending upon the amount of light on them and controlled by the increase in contrast due to the type of processing used. Dale's contribution is major toward the look of the picture.

It's difficult to tell where to begin in relating the contributions of our special effects team, headed by Henry Millar, Jr., his father, Hal Millar, and Jack Monroe. They gave life to the night with their low-hanging fog made with the help of a ton-and-a-half of dry ice. They created the eerie opening mood as the camera winds a circuitous route through archways and courtyard in a deluge of rain accentuated by thunderous crashes and blazing flashes of lightning. Since the castle is devoid of electricity, except for the laboratory, all the rooms are lighted by oversized fireplaces, huge candelabras, and wall torches. All had to be planned in advance, as the wall torches and fireplaces were piped for propane gas and then plastered up to look like two-foot-thick stonework. The wall torches had flame spreaders which added just the right amount of smoke for realism. The fireplaces had concrete logs. Real logs cannot be used, since they present a fire hazard and can't be turned on and off readily. There are various means of creating the firelight effect that bounces on the walls and the people in a room whose sole source of light is the fireplace. I chose to use silk strips of fabric fluttering in front of two or more lamps placed out of camera range. When these lamps were alternately brightened and darkened by dimmer control the firelight effect was quite realistic.

pre-determined spot.

To create a source of light simulating that coming from a solitary candle, we made a dummy candle out of an aluminum pipe. There was a hollowed top into which part of a real wax candle was placed and lighted; just below within an open slot of the pipe a 100-watt projection bulb was concealed and an electric wire was run up the sleeve and down the pant leg of the actor to a dimmer control. The actor's job, besides acting, was to keep the open slot of the enclosed bulb from being seen by the camera. This was a bit tricky when the candle was used to light the face. Then, as the actor passed the camera, the candle had to be rotated so that now the walls would be illuminated. The trick candle was a touchy affair that required a few extra takes. But, the automatic dart-thrower devised by Henry Millar, Jr. worked perfectly on the first take. It was a blow-pipe arrangement fired electromagnetically in any order for a sequence in which Dr. Frankenstein throws, in rapid succession, five bull's eyes as he attempts to impress Inspector Kemp.

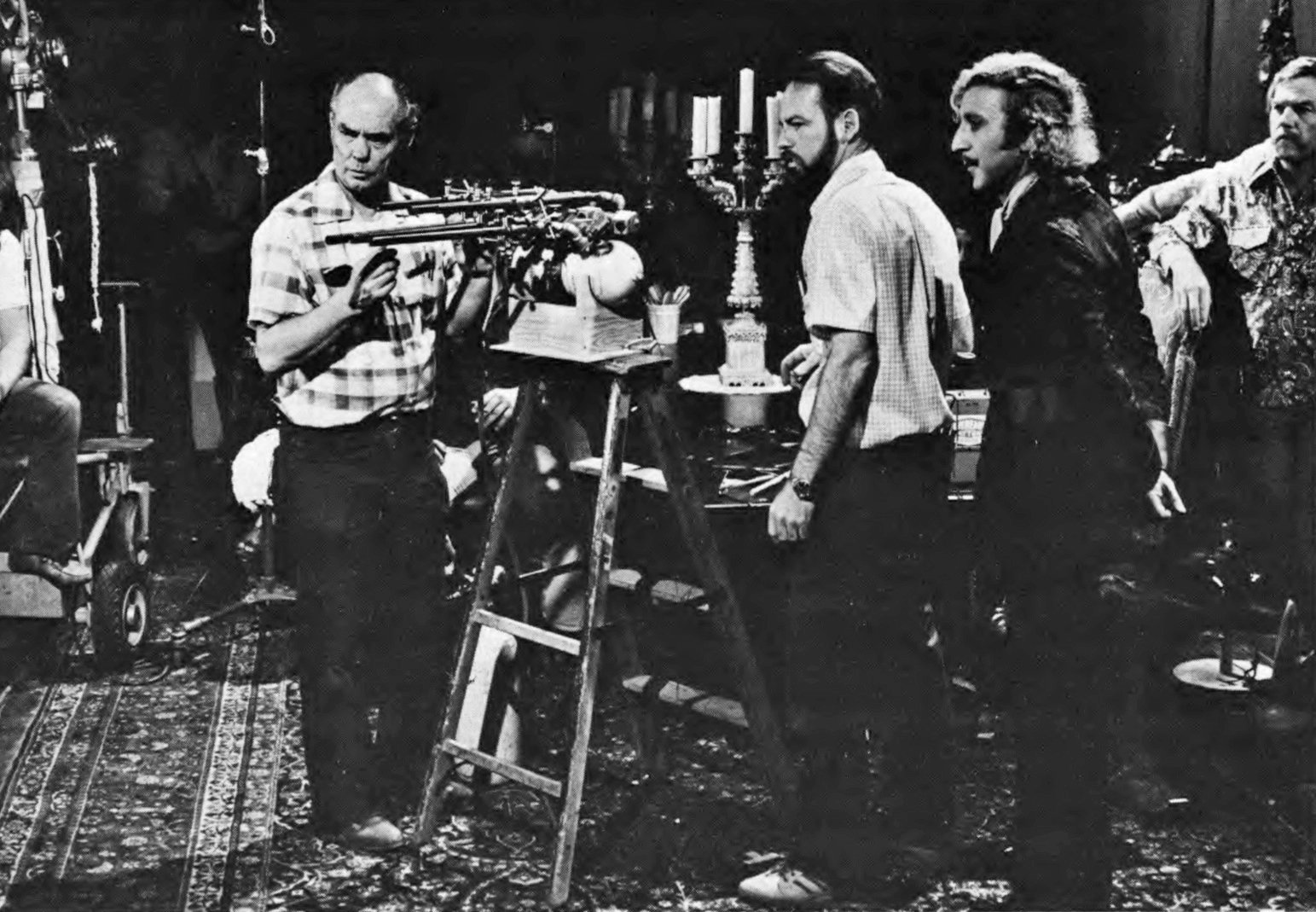

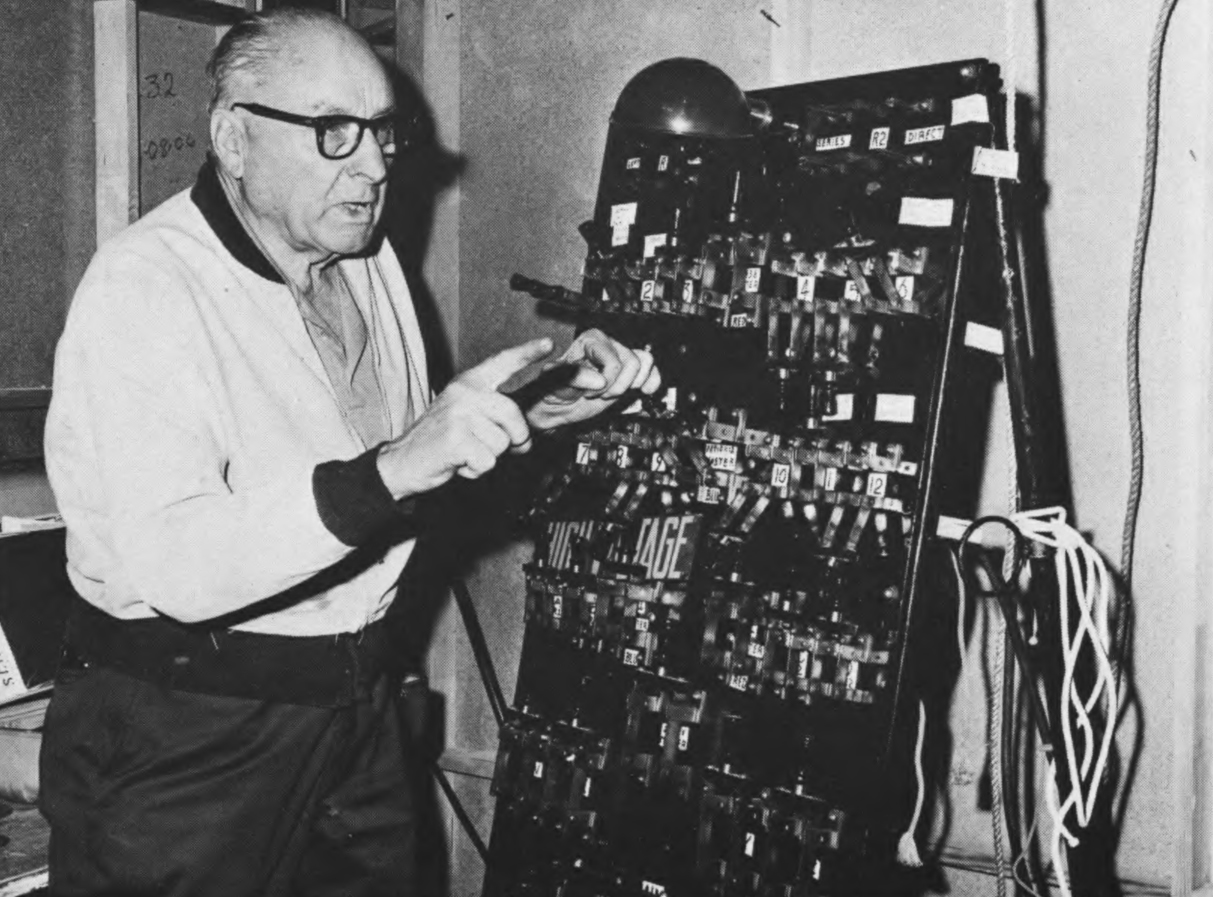

The electrical wizardry really impressed me. Upon researching the picture it was learned that some of the original Frankenstein electrical laboratory equipment was still stored in the garage of the man who designed it for the film made in 1931. This man, Mr. Ken Strickfaden, was on hand during all the laboratory filming to add his touch to the already fantastic array of bubbling vats and retorts and plastic tubes pumping blood solutions.

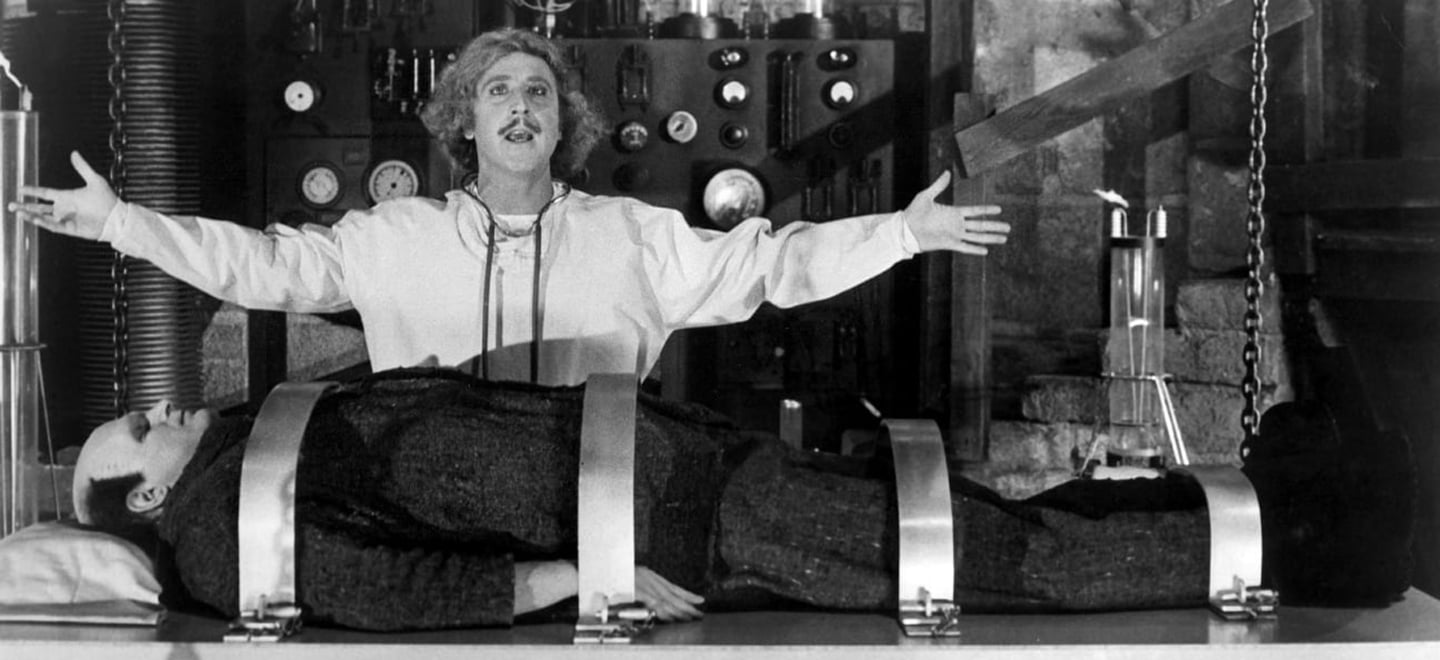

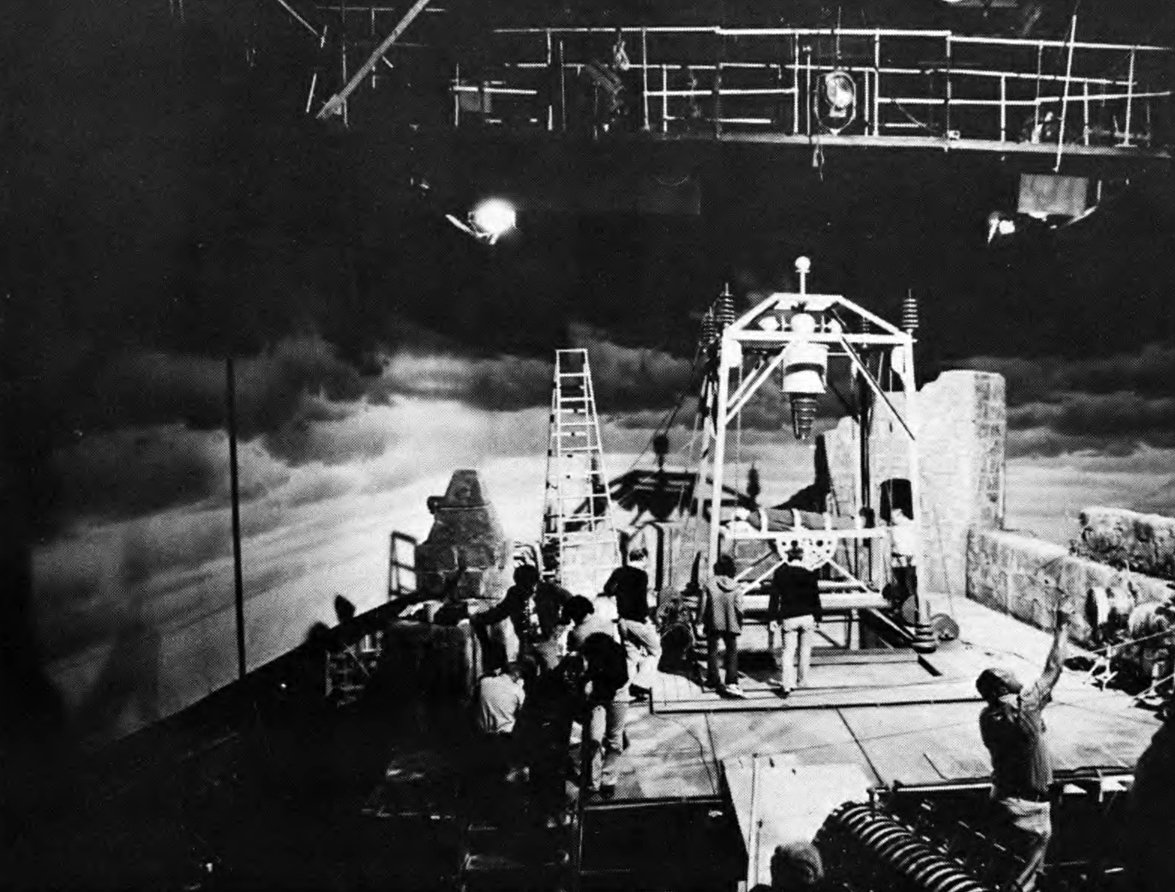

He also built new electrical devices specially for Young Frankenstein. The laboratory was ablaze at times with "Jacob's Ladders," which are spark-gaps that climb two V-shaped electrodes until the spark finally escapes at the top in a 6" span of lightning. The "Melodic Melinda," a humorously named gadget, created arcs that jumped from contact to contact in prescribed rhythym, from waltz time to jive tempos! Radial lightning devices shot their arcs in giant 6' circles, creating thunderous crashes on the set. But, the climax of this electric "circus" occurred when Dr. Frankenstein was hoisted by his assistants, Inga and Igor, by chains through the laboratory roof into the face of a tremendous lightning and thunderstorm. For those who may have forgotten, the theory that brings life to the dead components that the good Dr. Frankenstein puts together is the ultimate channeling of lightning into the dead body.

This effect was created on the elevated castle roof set; the "monster's body" and Dr. Frankenstein were raised from below and the operating platform was stopped directly beneath the terminal of a huge electrode. On "Action," Dr. Frankenstein lifted his hands heavenward, calling upon the tremendous power of nature to bring life to his creation. The special effects team, on cue, started throwing switches and an arc started to jump a mere two feet away from Gene Wilder, playing Dr. Frankenstein. It started leaping from the electrode to the body of the monster, growing in power and size until 500,000 volts were crackling through the air! Gene was safe as long as the distance from his body to the electrode was greater than that from the monster's body to the electrode. Needless to say, he remained cool, while the monster began to smolder, another effect created by secreting smoke machines under the operating table and releasing the smoke slowly through the inert body.

To complete our gamut of special effects we had to revert to old-fashioned process filming, the technique of projecting a moving background on a screen outside our Amtrack mock-up train and the Transylvanian train. This was to be the transition used to get young Dr. Frankenstein from his medical class in the United States to his castle inheritance in the remote country of Transylvania. Mel Brooks selected a modern night-travel shot to be used outside the modern train windows, but, nowhere could he find a stock shot of the stark, black, leafless trees and low-hanging fog, so indigenous to the eerie Transylvanian countryside, to be used outside of the Transylvania train mock-up. So, we made our own process plate. You may well ask how one does this on a sound stage? Here's how:

For some of our scenes in which the townspeople were hunting down the monster, Dale Hennesy designed a forest set that would chill the blood of a modern-day Dracula. It was about 40' in depth and about 100' long; we ran a dolly track parallel to it and made believe we were a train. But, in order to give the illusion of speed, the camera was run at eight frames per second and the dolly grip ran as fast as he could. We ended up with an effective 30 miles-per-hour process plate, but it was only about 12' in length! This would last only eight seconds when projected at 24 frames per second — hardly enough for a minute-and-a-half scene. The problem was solved by putting a large tree trunk at the beginning of the dolly track and another at the end of the track, close to the lens. All the editor had to do was to cut exactly when the frame was filled by the tree trunk at the end of the run and spliced on another print of the same scene using the tree trunk at the beginning of the run. By repeating this procedure, or by making a "loop” of the negative, we created 200' of Transylvanian forest going past at 30 m.p.h. and lasting a good two minutes on the process screen.

Throughout most of the first half of the film, the script called for bright flashes of lightning. There are several ways of making studio "lightning." The one my gaffer, Jim Plannette, and I decided upon because of the degree of control and intensity needed for our extremely large sets, was to use a conventional arc and reverse the polarity of the power to the carbons. When this is done, the arc will not burn properly but will continue to flash and sputter as long as the lamp operator forces the carbons together. This created a very realistic lightning effect and I let the lightning "burn up" the negative as part of the stylistic approach to satire. The director loved it.

We were making a comedy and, since the settings for this comedy were to be realistic and moody, my main problem was to maintain a low-key melodramatic visual look, but to be certain that all the comedic nuances of expression would not be lost in spooky lighting. This was no easy task and no single approach could solve the problem. At times, it was a hand-held "inky" lamp that bounced in just enough "fill light" to make the eyes visible. Had I used a normal fill light overall the mood of the scene would have been destroyed. Another time, the firelight effect was heightened to make the players that much more visible; or lightning was cued to make the humor of the scene stand out. The important point I had to remember was not to lose the so-called "joke." Even my operator had to alter his normal framing of a scene so that the "joke” was not lost to some far corner of the frame. Notwithstanding normal problems, our sound department, headed by Gino Cantamessa, did a fantastic job in not losing "jokes" while arcs all around were clicking out lightning, or the laboratory crackled with noises not wanted on the soundtrack.

As I recount the various special effects, the assortment of make-up creations, all the lighting effects, and my approach to filming Young Frankenstein, I find myself anxious to see the end result. A general rule-of-thumb in filmland is that it takes approximately nine months for the average-length film to be ready for exhibition, working from the start of photography.

I wait expectantly for our "baby" to be born.

The international trailer offers another view of the film’s comedy:

Hirschfeld passed in 2017 with over 50 credits on his resume ranging from 1948-1994. In 2007, he was honored with the ASC Presidents Award during the 21st Annual ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards ceremony, for his contributions to advancing the art and craft of filmmaking.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.