Adam Greenberg on The Terminator

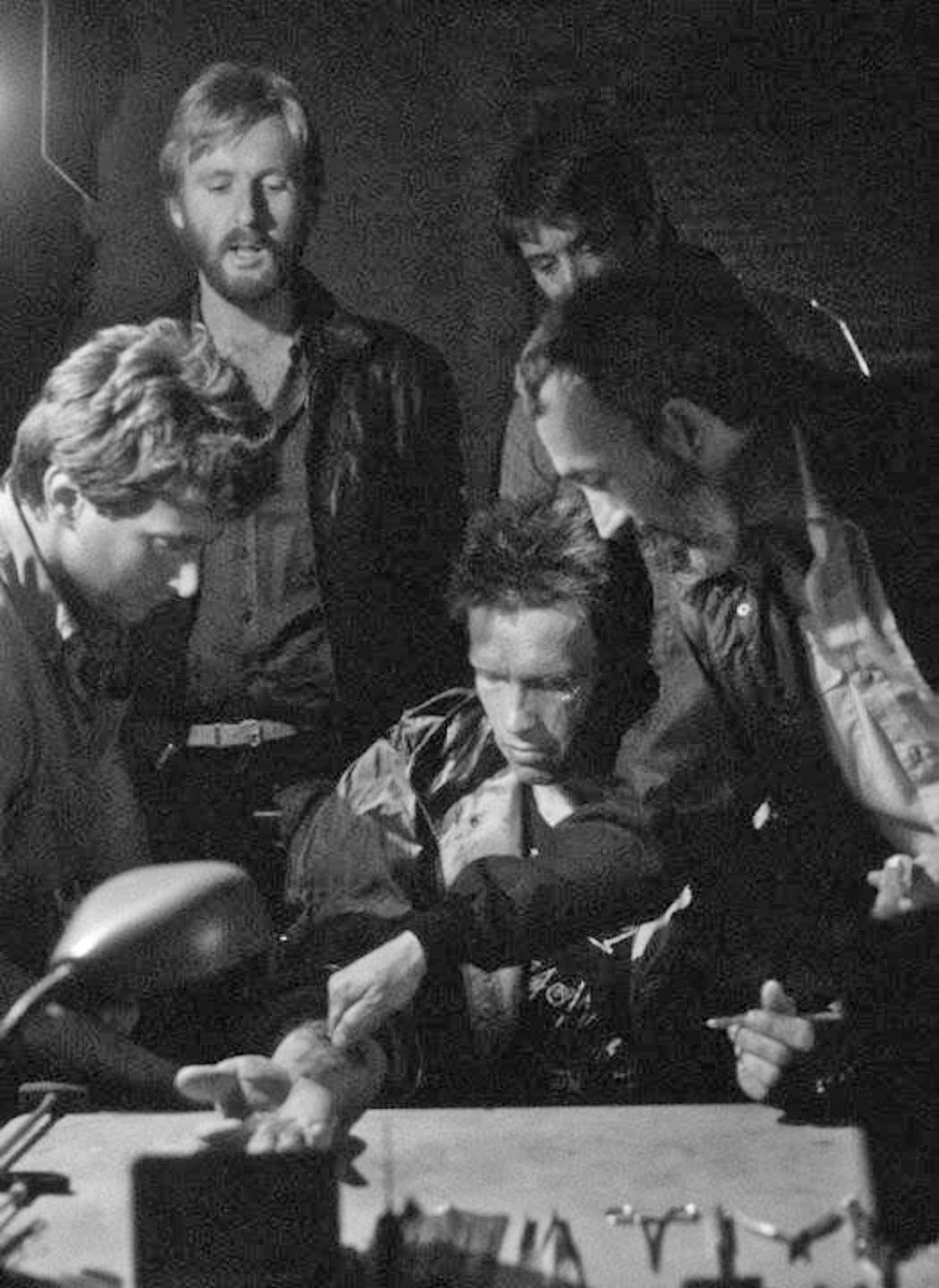

Cinematographer Adam Greenberg discusses his visual approach and collaboration with writer-director James Cameron on this sci-fi hit.

This article was originally published in AC April, 1985.

“The Terminator is living proof that you can make a $12-million movie for $6-million,” a filmmaker who saw it flatly stated. Another, thinking back to the audience-shaking “eye removal” sequence, said, “That sequence is a textbook example of how a special effect works in the mind of the audience, because absolutely nothing they’re reacting to is there on the screen.” The film, which came out with little advance publicity during the postsummer/pre-Christmas lull, has had audiences on the edge of their seats for several months now and became one of the most successful films of 1984.

Adam Greenberg, the Israeli cinematographer whose credits include The Big Red One, A Woman Called Golda, Operation Thunderbolt and whose work with director Moshe Mizrahi on the films I Love You Rosa and The House On Chelouche Street resulted in Academy Award nominations for Best Foreign Film in 1972 and 1973, respectively, found working on The Terminator as director of photography one of the biggest challenges of his 20-year career as a cinematographer.

LA Times critic Charles Champlin says that The Terminator owes more to 1940s film noir than to science-fiction. Director James Cameron states that his film influences are the German Impressionists of the ’30s, and film noir of the ’40s. "That was exactly how I saw it when I first read the script," says Greenberg. “I was aiming for a cool look, lots of dark shadows, strong backlight... a very hard, strong, contrasty look.”

In part, this look was dictated by the film’s budget. At $6 million, it is — for what it does — a “low budget” film. “This forced on me a lot of creativity,” Greenberg relates. “I accomplished most of what I set out to do by lighting and mood, rather than using a lot of elaborate equipment we couldn’t afford. Of my four electricians, three were trainees and two had never been on a set before.”

The Terminator is, in the words of its writer-director, “a gun ‘n’ run shoot-em-up.” There are a lot of high-speed chases around downtown Los Angeles at night, that look like they were filmed going 90 miles an hour. “What I did,” Greenberg reveals, “was have lights on dimmers mounted on cars accompanying us. The lights would operate faster than the streetlights, giving the feeling that we were going very fast. Actually, the cars were never driven faster than 40 m.p.h., but those lights gave the illusion of an extra 25-30 m.p.h.”

Indeed, illusion was the name of the game throughout the production of The Terminator. “In the alley scene, where the Terminator comes out of the fire and jumps on the hood of the car,” Greenberg explains, “it looks like the car is accelerating backwards rapidly. Actually, the car was standing still. They built a false building wall, which was moved past the car, and the dimmer lights provided the illusion of speed.”

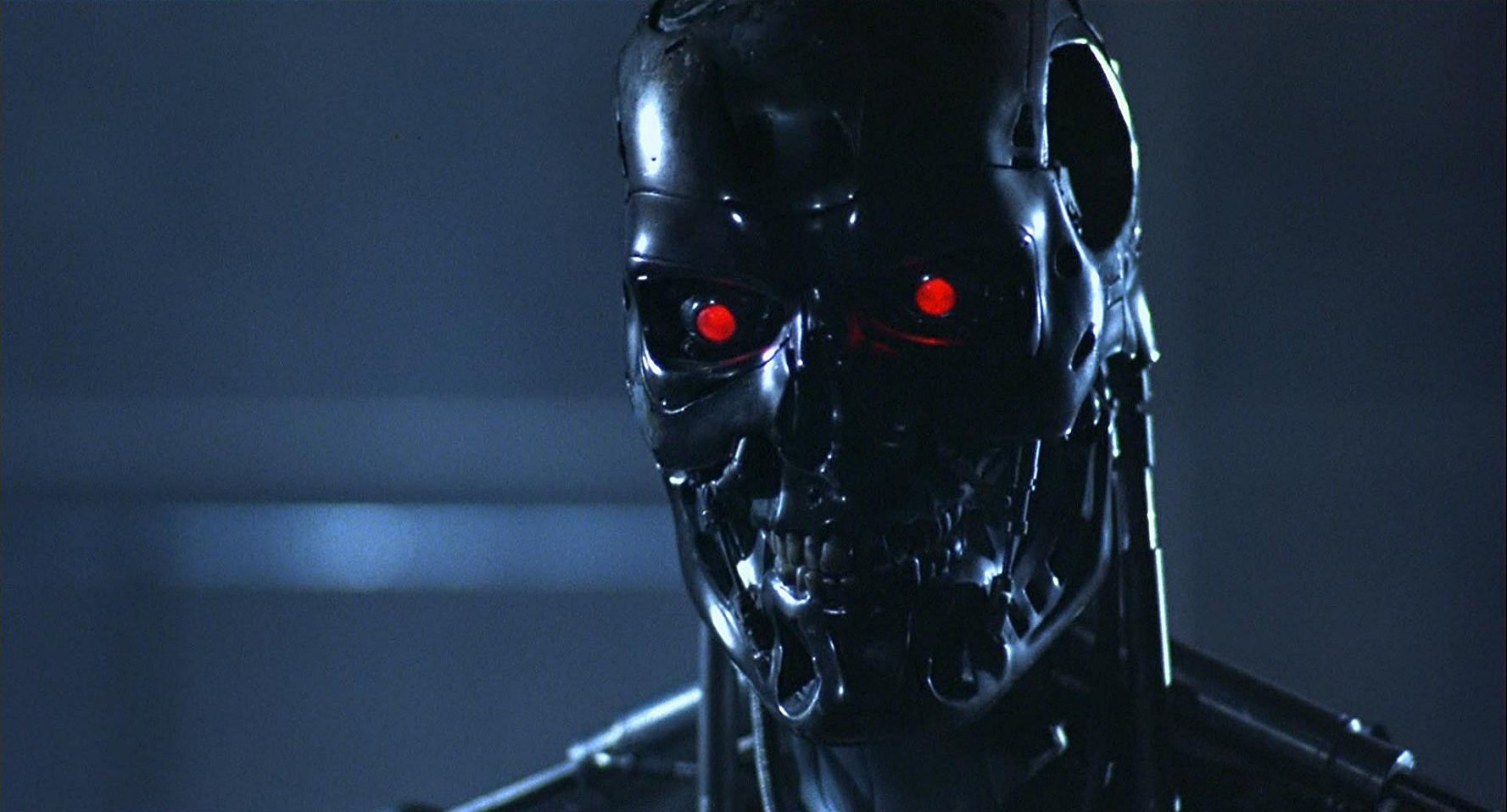

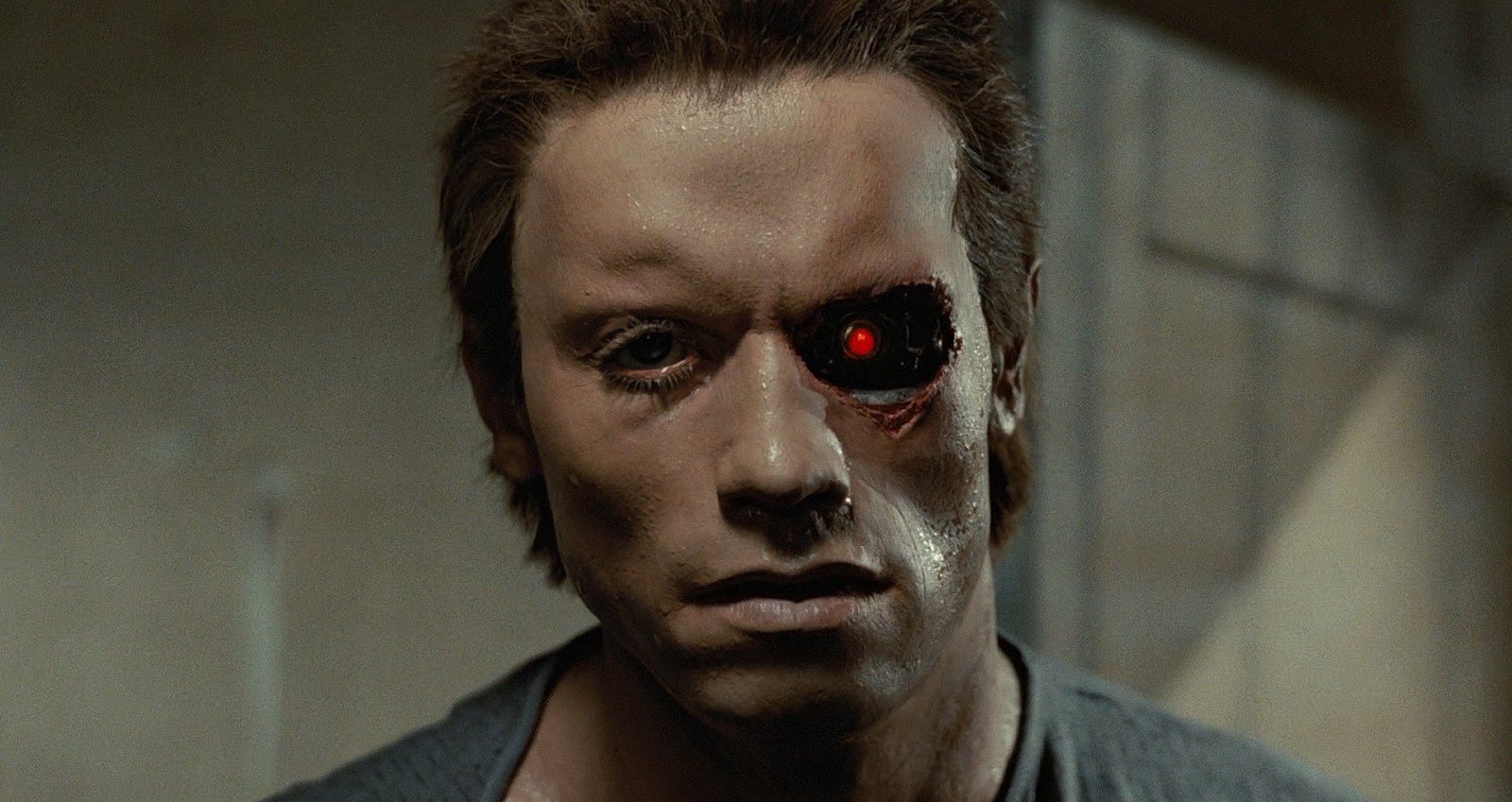

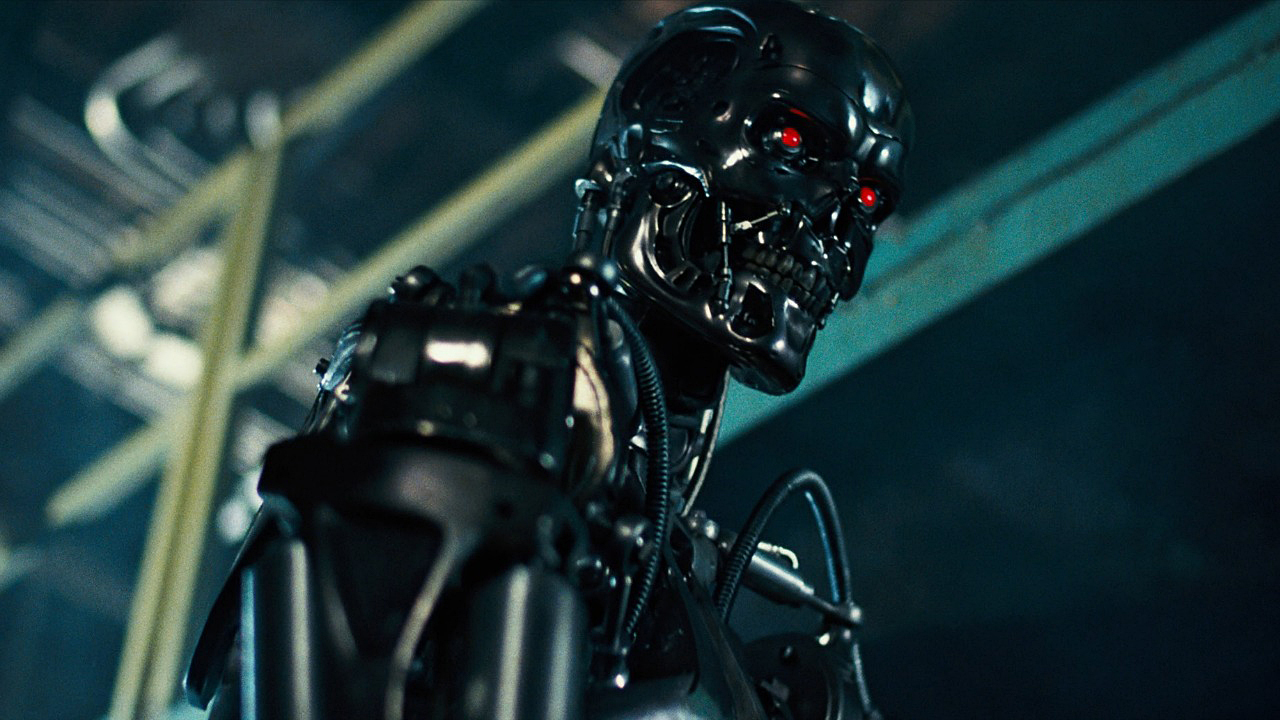

The sequence which seems to stick most in the minds of those who have seen the film is the “eye scene,” in which the Terminator makes emergency repairs on itself after a gunfight with the hero. Cameron here made use of his background as a special effects art director. “You have to give the audience a certain level of effects,” he stated, “after which they will make their own connections. Done right, you can do these things for much less than other people would think. Give the audience ‘A’ and ‘B’ correctly, and they will supply their own ‘C’.” Indeed, it is classic. First, the Terminator operates on his arm —a prosthetic built by effects wizard Stan Winston — stabbing it with a Number II Xacto blade.

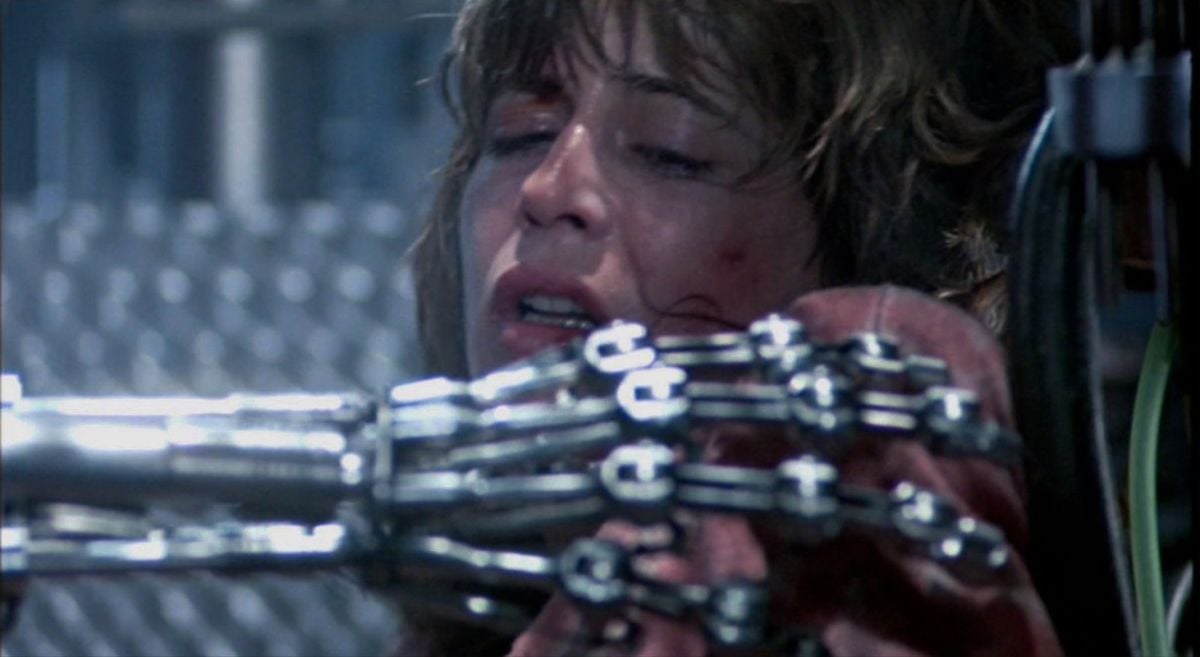

The audience is then shown him working on the metal interior of the arm. He steps to the sink, examines his eye, and then —with the camera shooting from the right as he works on his left eye — he brings up the knife and poses it in front of the eye. A quick cut to close-up of the eye lens dropping in a sink full of water that turns red, and nearly everyone in the audience is completely convinced they have seen him remove the eye.

“Most of this is possible because the audience does not see everything that’s going on,” says Greenberg. “Most of the screen is filled with dark shadows, which the audience fills in with imagination.”

Greenberg believes that shooting on a lower-budget promotes this kind of creativity. “If you have more money to spend, you throw away more. This movie is 95 percent what I imagined it would be when I first read the script.”

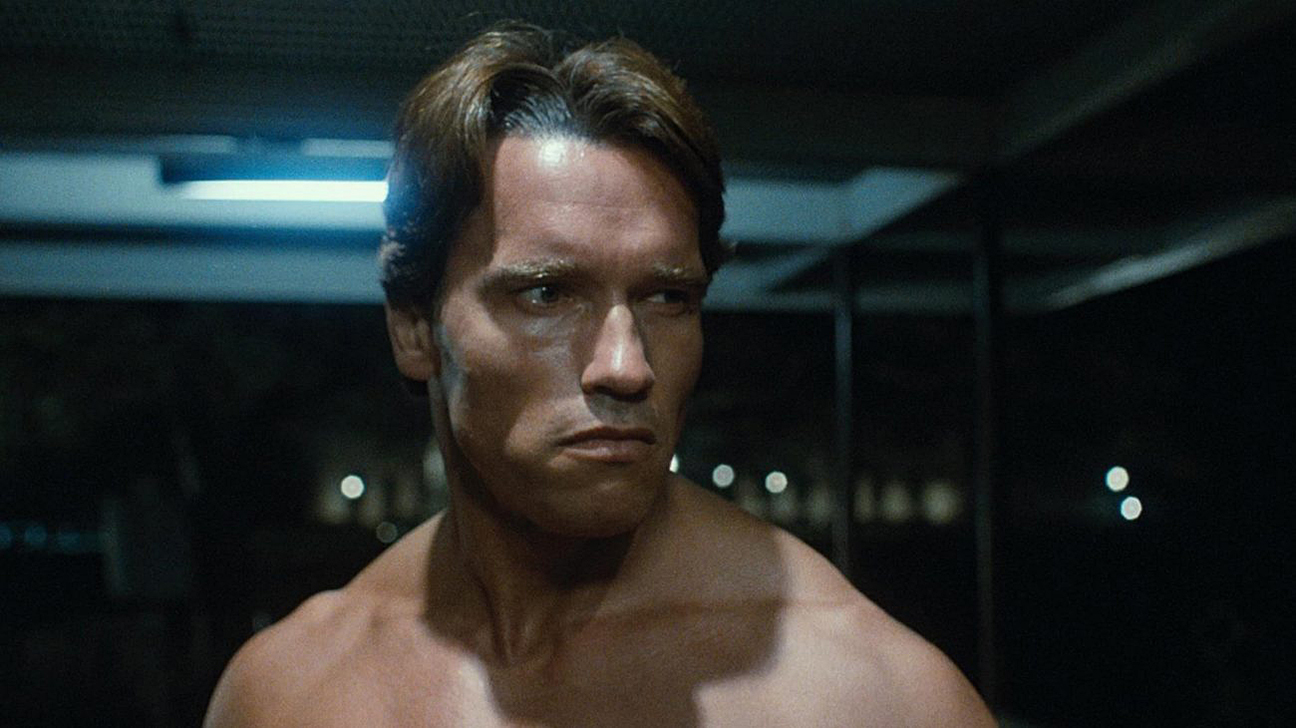

Much of the camerawork in The Terminator is handheld. “To me,” Greenberg states, “shooting handheld gives an energy to a scene you can’t get any other way.” At first there was thought of using a Steadicam for much of this, but budgetary constraints precluded that. “I got together with my gaffer and came up with a very simple device that allowed me to do what I wanted, shooting handheld,” Greenberg relates. What was wanted was the ability to have the camera on the floor for extreme low-angle shots, since that was the photographic method used to stylize actor Arnold Schwarzenegger as the robot Terminator. “He’s big to begin with,” says Greenberg, “but doing all those low angles makes him look like a monster.”

The Terminator's impressive size is established in an early scene, in which he confronts a trio of punks after teleporting in from the apocalyptic future.

The Terminator's impressive size is established in an early scene, in which he confronts a trio of punks after teleporting in from the apocalyptic future.What developed was a piece of equipment the crew came to call “The Adam Camera.” Basically two L-shaped pieces of aluminum tubing with a camera mount on one end and a tie-down for sandbags at the other, the mount allowed Greenberg to run with the camera, with the lens on ground level. “I was doing my shooting through a video monitor,” he explains. This rig was used in the disco shootout scene where the soldier Reece (Michael Biehn) first saves the heroine Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) from the Terminator, and the shootout in the police station where the Terminator reduces everything to a bloody pulp. “We also used it a lot in the future scenes. Those were actually more difficult because in the other scenes the floor in the location was all smooth and I could go anywhere. In those scenes, I couldn’t.”

To Greenberg, lighting is everything. “One thing that makes me happy is that everyone thinks the film was shot using available light. The truth is, I used a lot of light, but it seemed very naturalistic. When I’m shooting, I am always very conscious that I’m shooting actors, not locations. I have to shoot for the actor, for his character, what will look right and say the right things about the actor and character.”

“Usually by the second day of shooting, I know just what kind of lights each actor needs. I can have six actors in a scene, and each will have his own light. With Linda, I used very soft, very natural lighting to make the statement about her character. For Michael's character, I used shadows, hard shadows, giving a ‘hard edge’ to him. For Arnold, I was using harsh light that gave a mechanical look, and then a lot of low angles, almost all low angles, to emphasize size.”

“I particularly like working with a director who has a personal vision of the project,” Greenberg states. “If he has that, there’s a much better chance that something worthwhile will come out of it than if it’s something someone brought to him, or something he was just hired to do. There’s something additional — something you can't put into words — when the director has his own private story. He has better control."

To Greenberg, the best examples of this come from his work with Moshe Mizrahi on I Love You Rosa and The House on Chelouche Street, and Samuel Fuller on the World War II drama The Big Red One. “Mizrahi was telling stories that came out of his life, the experiences of people he knew," Greenberg explains, “and Sam Fuller was telling the story of the most important things that ever happened to him personally.”

As a cinematographer, Greenberg prefers location work to studio shooting. “I like to go away to shoot, away from my family, to be isolated from the rest of the people I know in life. It’s the best way to concentrate. To me also, location shooting gives an edge of reality to what’s being done that can never be recreated in a studio. This preference probably comes from having begun my career as a news cameraman, then moving into documentary filmmaking.” The bottom line, however, is this: “For me, working on a movie anywhere is a vacation. No matter how hard it is, it’s not ‘work.’”

Greenberg’s lifelong love affair with movies began as a child. “I always wanted to go to the neighborhood cinema when I was a boy in Israel. I loved the movies, they were magic.” Later, as he became more seriously interested in film, “... it was the French New Wave, particularly Godard with his camera work, and Chabrol. They opened things up and took the movies out into the real world where people lived.”

So far as the influence of other cinematographers is concerned, Greenberg is an avowed fan of Vittorio Storaro. “His work is head and shoulders above everyone else, to me. When I go see a film he’s shot ... it doesn't matter what the story is or who’s in it. Storaro is the greatest so far as I’m concerned.”

With a film as successful as The Terminator in his credits, Greenberg finds the offers to work coming in from all quarters now. “When I choose a project though, it’s not for how much money is involved. I like to work and I’m not going to be poor, but I’m not in it to become very rich. I look at the story, what it’s about, what it’s saying about things. I look at who’s involved. Are they people I want to meet, to work with. The story and the filmmakers. That’s much more important than the money.”

Greenberg re-teamed with Cameron to shoot Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), for which he earned an Oscar nomination, while his feature credits also include Iron Eagle, Near Dark, Three Men and a Baby, Alien Nation, Ghost, Sister Act, Junior, First Knight, Eraser, Sphere, Rush Hour and Snakes on a Plane.

Greenberg was invited to become a member of the ASC in 1990 and is now retired.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.