The Two Faces of Dracula

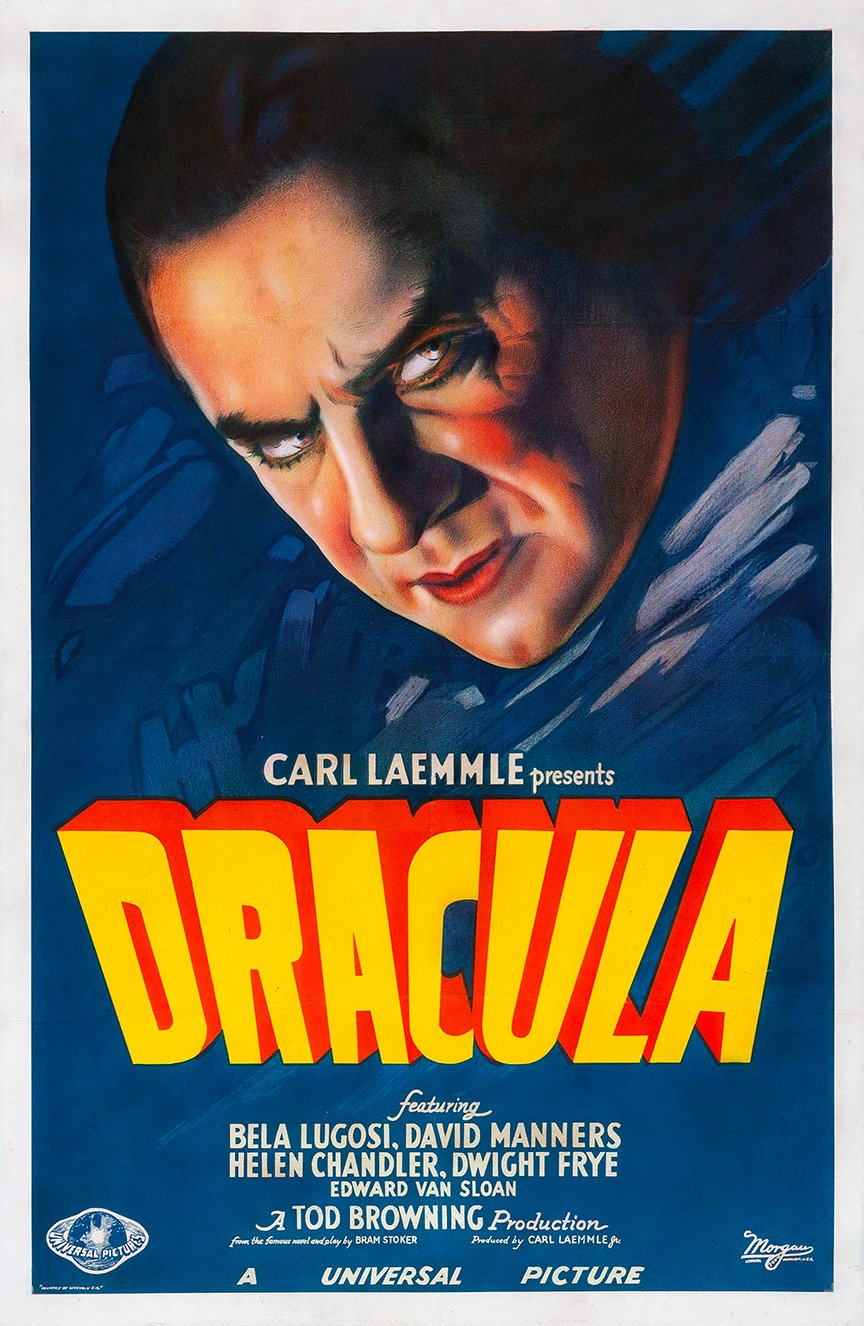

Examining the history and legacy of Universal Pictures’ classic 1931 horror drama — presented in two forms — which resonates to this day.

This article originally ran in AC May 1988.

On February 14, 1931, New York impresario S.L. Rothafel delivered an unusual Valentine to the patrons of his Roxy Theater. Advertised as “... the story of the strangest passion the world has ever known,” Dracula corralled the customers in droves. Of greater importance, ultimately, is its trailblazing position as the forerunner of a genre which has ebbed and flowed as a film perennial ever since: the supernatural horror “talkie.”

It's true that a number of sound pictures of the spine-chilling variety had preceded Dracula, including such popular numbers as The Terror, Stark Mad, The Cat Creeps, The Bat Whispers, and The Gorilla. Most of these were adapted from Broadway plays in which the scary stuff was intermingled with comedy and anything that appeared paranormal was always revealed as the machinations of malevolent human beings. What made Dracula different was that the audience was expected to accept the villain as a genuine vampire and not another crook in disguise. There was a strong feeling in the industry that the producers were insane to ask moviegoers, who had just emerged from the Roaring Twenties and stumbled into the morass of the Great Depression, to suspend disbelief in a Medieval superstition.

Actually, Dracula proved that hard times enhanced the charm of such a picture. The movie companies found in short order that realistic stories which tried to come to grips with the realities already bedeviling the public were not generally popular. After all, the idea of a 500-year-old Carpathian nobleman surviving on the blood of lovely young English ladies was only slightly more fantastic than such popular fare as Westerns, murder mysteries, musical comedies, the Marx Brothers, and Hollywood’s notions of romance among the millionaires. The allegorical aspects of a tale in which an evil outside force intrudes upon the lives of ordinary people who manage to overcome the menace may have triggered subconscious responses from a populace beleaguered by destructive forces against which it was helpless. The grimness of the theme was alleviated by its abnormality — viewers could forget for a time the realities of the Depression and share vicariously in problems that they knew would never touch their own lives.

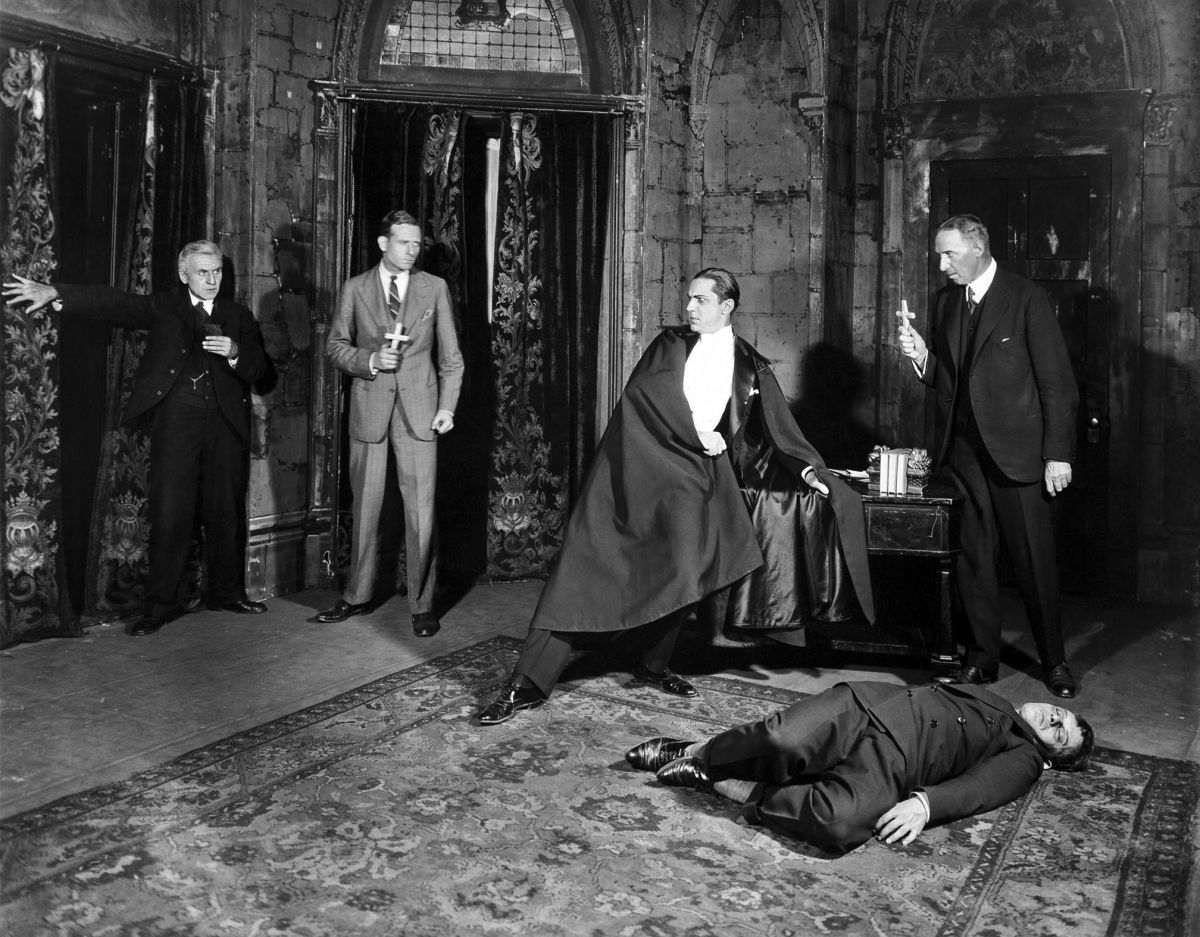

It is difficult today to understand why Dracula was considered such a gamble in its day, and why, in light of the truly gruesome films that have come in its wake, it was repugnant to many who saw it. Whatever its faults, the picture is done in admirable taste. The only show of blood is a single drop on a man's finger following an accident with a paper clip; even those telltale “two little marks” that are discovered on the necks of the vampire’s victims are kept discreetly out of sight of the camera — and there is only one instance of on-screen violence. Yet this picture, now more admired for its atmosphere and the commanding presence of Bela Lugosi than for any ability to horrify, stirred controversy when it first appeared.

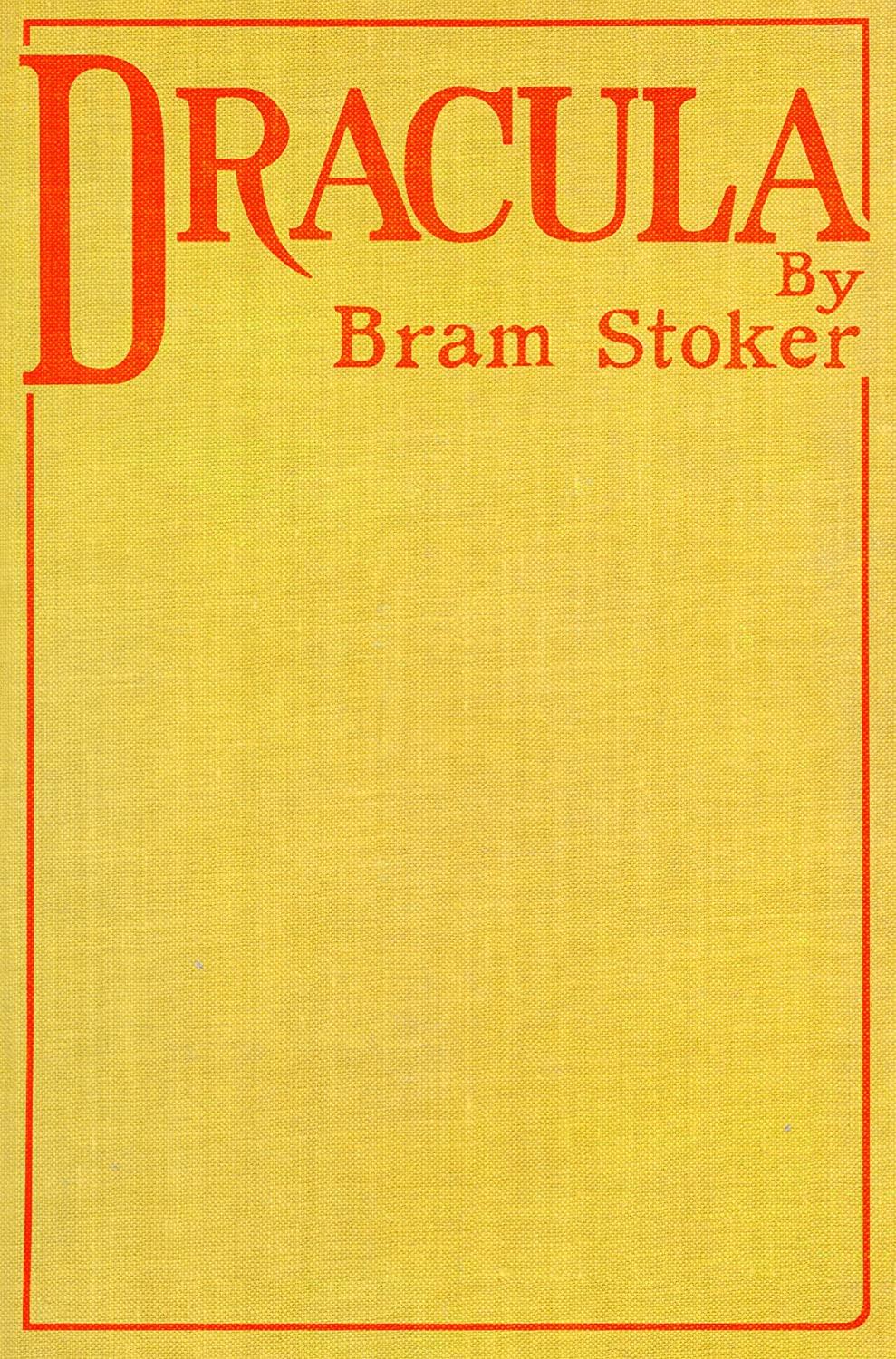

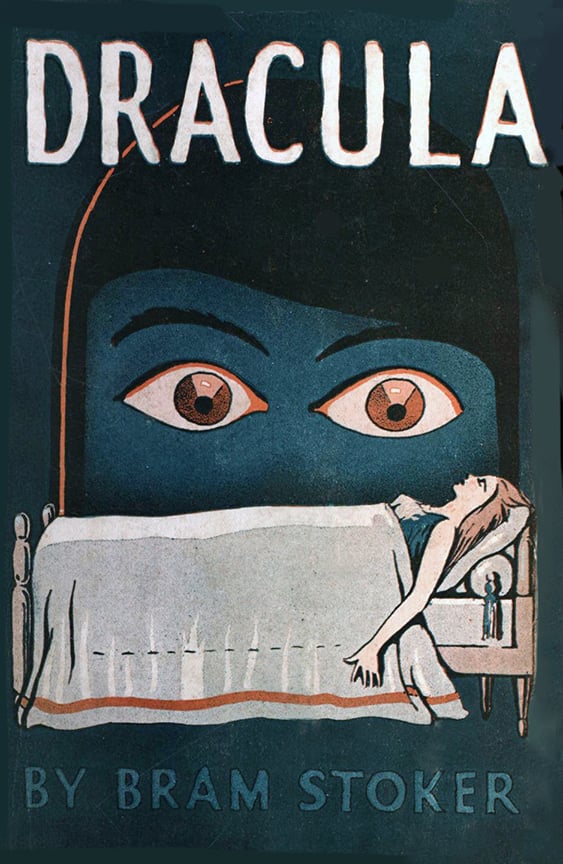

Bram Stoker’s book, published in England in 1897, was suggested by Central European vampire legends, which for many years had been utilized by authors of Gothic novels, and the historical accounts of a Wallachian warlord whose cruelty had earned him a reputation of being in league with Satan. From these sources emerged a remarkable work in which the vampire, instead of being a crawling graveyard creature, is a Transylvanian voivode possessing fantastic strength and the magical ability to transform himself into a wolf or bat or wisp of vapor, to command animals and storms, and to hypnotize humans and animals at a gesture. He can walk only by night, casts no reflection, and is practically immortal so long as he feasts regularly on the blood of the living, stays in his grave during the daylight hours, and doesn't encounter anyone so unkind as to drive a stake through his heart during a nap. He is a withered ancient with white hair and fetid breath, but after feasting he takes on a younger, less forbidding appearance. He fears the Christian Cross and is violently allergic to garlic and wolfbane.

In Germany in 1921, the brilliant F. W. Murnau directed a highly effective unauthorized version titled Nosferatu but released in England as Dracula. The vampire — Baron Orlok in Germany, Count Dracula in England — was a rat-like, ghoulish creature. Stoker sued, but the production company (Prana Film) had gone broke and the plaintiffs had to be content with having prints destroyed. Fortunately, the picture survives as an excellent example of the German Expressionist school.

In 1924, an English provincial play producer and actor, Hamilton Deane, wrote an authorized stage production that proved so popular that he soon had two touring companies on the road. He didn’t muster the courage to present it to a London audience until 1927 when he opened it at the Little Theatre on February 14 with Raymond Huntley as Dracula and himself as the vampire’s nemesis, Professor Van Helsing. Despite a drubbing from the critics, the play ran for 391 performances. An American producer, Horace Liveright, saw it in March and purchased rights to produce it in the United States. John L. Balderston, London correspondent for the New York World and a noted playwright, adapted the show for Broadway. It opened at the Fulton Theater on October 5 to mixed reviews and an enthusiastic audience response.

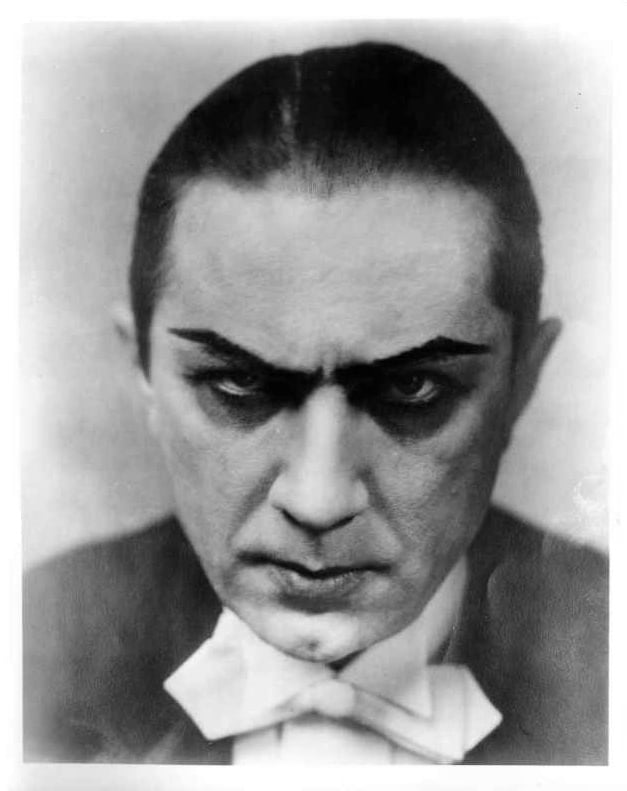

The title role was played by a young Hungarian emigre, Bela Lugosi, whose dignified but saturnine appearance and heavily accented delivery created a romantic, urbane image far removed from the repulsive ancients envisioned by Stoker and Murnau. The play ran for 261 performances in New York, then went on the road with great success.

About four months before the Broadway version opened, Universal Pictures considered making a silent screen adaptation. After studying the Stoker book, most of the studio readers concluded in their reports of June 15 that as screen material Dracula was “... out of the question... it would be an insult to every one of its audience... passes beyond the point of what the average person can stand or cares to stand.” A minority opinion averred that:

“For mystery and bloodcurdling horror, I have never read its equal. For sets, impressionistic and weird, it cannot be surpassed. This story contains everything necessary for a weird, unnatural, mysterious picture... It will be a difficult task and one will run up against the censor continually, but I think it can be done. It is daring but if done there can be no doubt as to its making money.”

In October, following the opening of the New York play, Universal reassessed the work. The majority conclusion was that although it could make “a great picture... from the angle of the pictorial and the dramatic, it is not picture material from the standpoint of the box office nor of ethics of the industry.”

In 1929, Universal got a new chief studio executive: Carl Laemmle Jr., five-foot-three, 21-year-old son of the company’s president. Eccentric and hypochondriacal, Junior Laemmle had some ideas that ran contrary to those of many of the studio old-timers. One of them was to put Dracula into production on a grand scale. Despite the opposition of his advisors, Laemmle Sr. — with considerable trepidation — okayed the project. Rights to book and play were acquired for $40,000 and in June of 1930, Fritz Stephani completed a 32-page treatment. It was announced that “almost $400,000” would be spent on the production — an impressive sum from a studio in financial trouble at a time when half that amount constituted an “A” budget.

Other writers — including Louis Stevens, Louis Bromfield and Dudley Murphy, contributed to the evolution of the shooting script, which eventually was completed by Garrett Fort.

The Bromfield screenplay, which was based primarily upon the book, could have been an almost definitive version of the subject, but it was rejected as being vulnerable to censorship as well as difficult to produce as a sound film because of the considerable outdoor action. The final script restricts most exterior photography to the first 25 minutes of the picture, then keeps the action indoors except for a few short scenes.

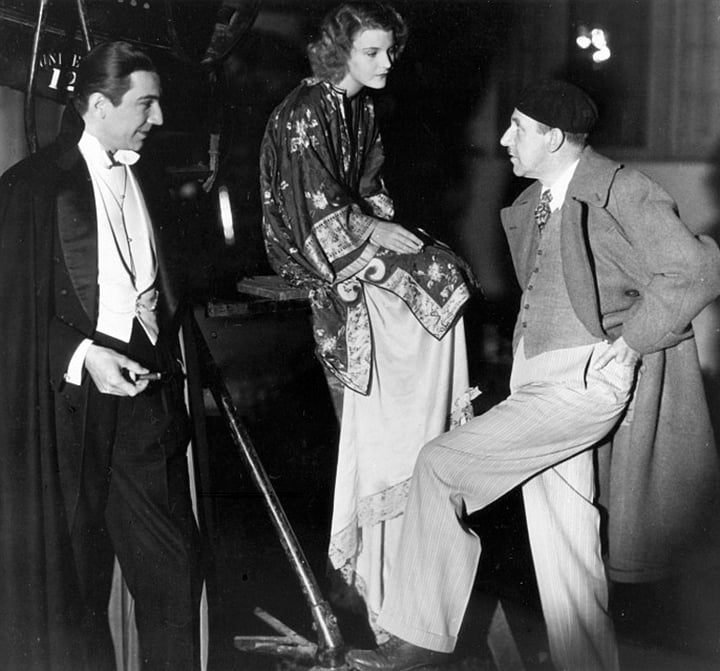

Tod Browning, a veteran director who specialized in the making of weird and unusual pictures, including some of Lon Chaney’s successes at Universal and MGM, was signed for Dracula. Browning said that he and Chaney had discussed making the story as a silent film years before, but concluded that it couldn’t be done successfully without dialogue. Now the era of talking pictures had arrived, but it was too late to consider Chaney, who was dying of cancer after having completed his first and only talking picture, The Unholy Three.

Universal’s replacement for Chaney when he moved to MGM had been German actor Conrad Veidt, who performed superbly in several Universal silents between 1927 and 1929 — including the marvelous The Man Who Laughs and the part-talking The Last Warning. Veidt returned to Germany, however, when faced with the prospect of making talkies in English. Laemmle Jr. considered bringing Veidt back for Dracula. There is no question that Veidt would have been ideal for the role, but he was not disposed to leave Europe at the time.

Passing over Lugosi as not being sufficiently well known, the studio considered Fox Film’s character star from the stage, Paul Muni; the darkly handsome Ian Keith, a brilliant actor then in disfavor because of a drinking problem; and the distinguished stage actor, William Courtenay. Eventually, Lugosi was brought in for tests. In mid-September, he signed a two-picture contract for $500 a week.

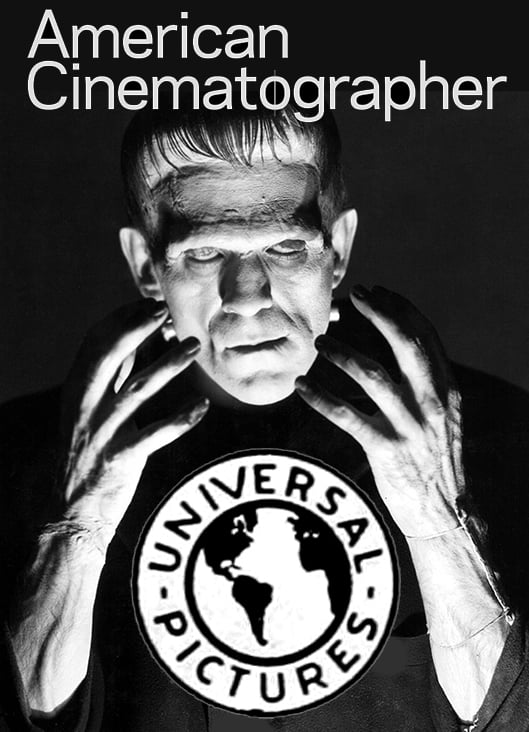

Karl Freund, ASC, the most celebrated cinematographer of Germany's "Golden Age" of expressionism, was assigned to Dracula, his first American film. His German credits included Variety, Metropolis, The Last Laugh, The Golem, Symphony of a City, and other revered classics of imaginative cinema. Born in Bohemia in 1890, he had been a movie technician and cameraman since 1906. He was also an inventor, owned a film lab in Berlin, and was a director and producer for Fox Film in Germany. When he came to America in 1930 to tout a color process in which he had a proprietary interest, William Stull, ASC — then serving as the Society’s secretary — informed Freund that “... at the last meeting of the Board of Governors of the American Society of Cinematographers, you, as Europe’s foremost cinematographer, were unanimously elected to Active Membership in that society.”

Freund gravitated to Universal, which he had visited in 1924 while Phantom of the Opera was being made there. Arthur Edeson, ASC, then Universal's top-ranking cinematographer, championed him as "a great photographer" and "Uncle Carl" Laemmle, who was extremely loyal to his native Germany, welcomed him with open arms. Freund ingratiated himself quickly by suggesting the perfect ending for All Quiet on the Western Front that had eluded the writers.

To call the short, rotund Freund “colorful” would be to understate the case. He could be gracious and charming at one moment, cool and distant in the next. When directing, he proved to be a hard-boiled, Prussian-styled taskmaster in the tradition of his mentor, Fritz Lang. A handful of directorial assignments from 1933 to 1935 (The Mummy, Moonlight and Pretzels, Uncertain Lady, The Countess of Monte Cristo and Mad Love), all of which were realized with speed and resourcefulness, prove him to have been a brilliant and imaginative director.

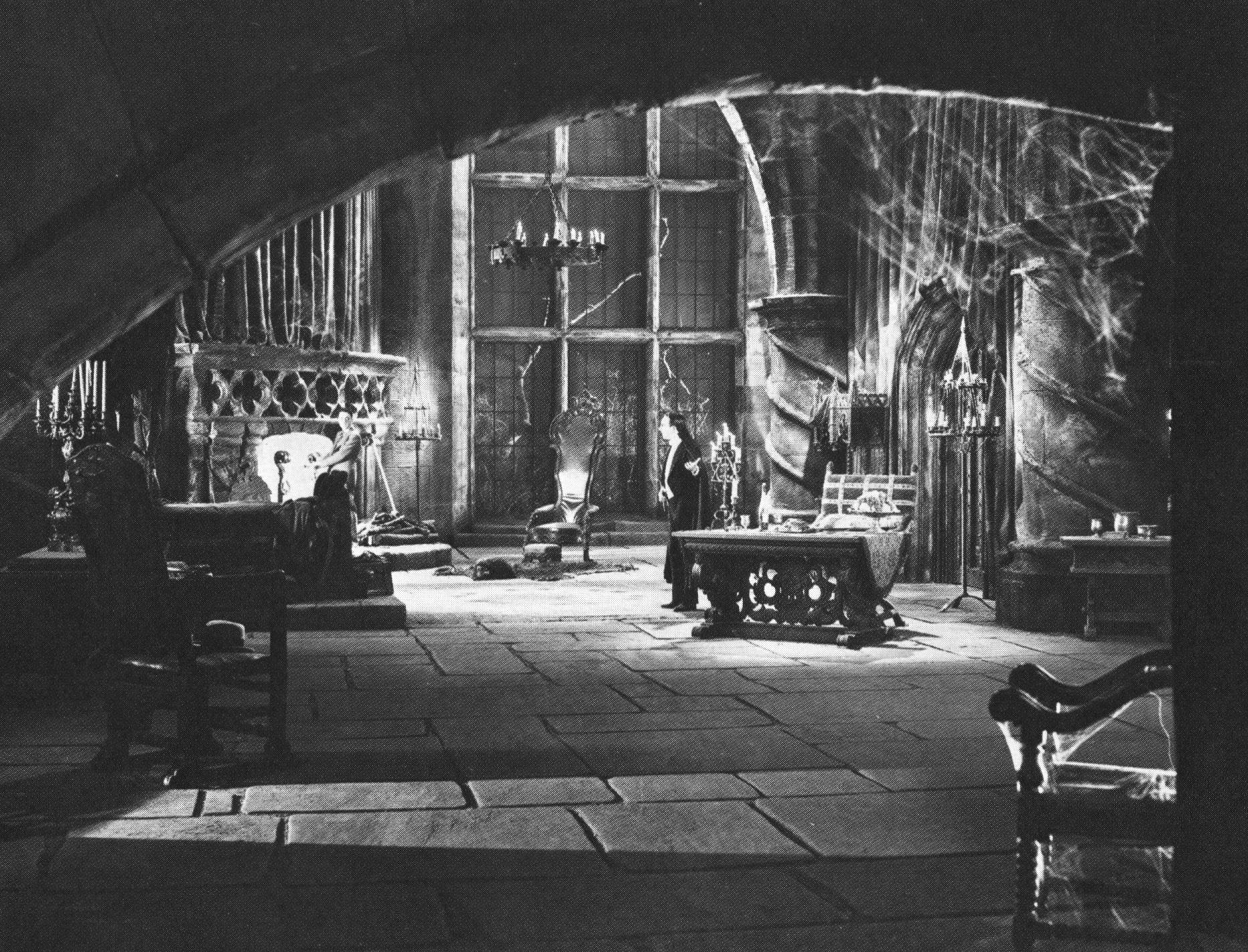

Universal’s supervising art director, the very British Charles D. Hall, made a number of idea drawings for key sets, including the much-imitated cellars of Dracula’s London home, with its massed groined arches and monumental stairway. He was assisted by two remarkable artists, Herman Rosse and John Hoffman. Rosse, a noted stage set designer from the Netherlands, had come to Universal with Broadway director John Murray Anderson for the spectacular King of Jazz, which won him an Academy Award for 1929-’30. It was Rosse who saved a chunk of the set budget for Dracula by designing the spectacular facade of Castle Dracula so it could be pieced together with portions of disassembled Medieval sets from the silent days. Hoffman was one of those brilliant but little-known artists who worked behind the scenes at the major studios. He designed sets for several early talkies, but later switched to directing, special effects photography, and, most notably, to creating montage sequences.

Budgeted at $355,050 and scheduled for 36 shooting days, principal photography was begun on September 29 on the backlot country inn set. The picture was completed November 15, after 42 working days, at a negative cost of $341,191.20. Added scenes were shot on December 13, and retakes were made on January 2, 1931.

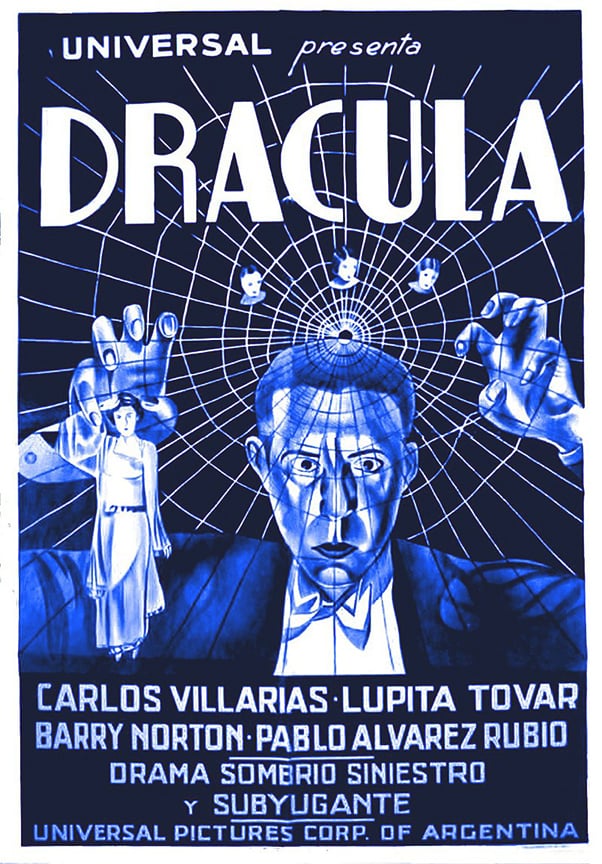

A Spanish language version of Dracula, utilizing the same sets but with a different cast, producer, director and crew, was begun on the night of October 23, 1930. The producer was Paul Kohner, who later founded a leading talent agency but at the time was head of Universal’s foreign department. Czechoslovakian-born and Vienna-educated, the tall and personable Kohner had been a production supervisor at Universal for years and was the producer of an excellent silent spectacle The Man Who Laughs. It was because he fell in love with Lupita Tovar, a beautiful actress from Mexico who was playing small parts at Universal, that Kohner talked Carl Laemmle Sr. into letting him make Spanish-language productions.

“Lupita told me she couldn’t make enough money at Universal and she was going back to Mexico,” Kohner said in early 1988. “I lay awake all night trying to figure a way to change her mind. I went to Uncle Carl and told him that I could make Spanish versions of his pictures for about $35,000 each by using the same sets after the regular company had quit for the night. He agreed to give it a try with The Cat Creeps. I put Lupita in Helen Twelvetrees’ role, the picture was a great success, and she decided to stay in Hollywood.” Following a triumphant tour of Mexico, the petite actress was assigned the feminine lead in the Spanish Drácula. She also became Mrs. Kohner. The marriage was happy and enduring.

George Melford, a veteran director of the hard-boiled school, who was best known for the Rudolph Valentino silent, The Shiek, directed. The cinematographer was George Robinson, ASC, undoubtedly one of the most underrated artists in his field. The adaptation was the work of the scholarly Baltazar Fernandez Cue, who did most of the Spanish language screenplays made in Hollywood. In the cast were Carlos Villarias as Dracula, Lupita Tovar as Eva (Mina), Barry Norton as Juan, Eduardo Arozamena as Van Helsing, Carmen Guerrero as Lucia, and Pablo Alvarez Rubio as Renfield. Villarias somewhat resembled Lugosi and obviously patterned his portrayal after him, only to come out second best. The other players seem not to have been influenced by the first-string performers. Tovar and Rubio are very good. The special effects scenes and some of the exteriors and long shots from the first unit production were utilized for the Spanish rendition.

Both versions of Dracula open with a glass shot, which was photographed by Frank Booth, of a horse-drawn coach coming at breakneck speed down a mountain road in the wilds of Transylvania. Swirling mist is superimposed over the scene, which was photographed northeast of Los Angeles at Vasquez Rocks, whose angular hogback formations blend flawlessly into the artist’s towering peaks. A young English passenger, Renfield, admonishes the driver to slow down, but is ignored. A local rider explains excitedly, “We must reach the inn before sundown! It is Walpurgis Night, a night of evil. Nosferatu! On this night... the doors, they are barred, and to the Virgin, we pray.’ The coach arrives at the inn, where there is rejoicing that the coach arrived in time. The innkeeper, learning that Renfield plans to continue on to a midnight rendevous with Count Dracula at Borgo Pass, tries to talk him out of it. “We people of the mountains believe that Dracula and his wives are vampires,” he explains. “They leave their coffins at night and they feed on the blood of the living.” Renfield boards the coach after accepting a crucifix from a peasant lady who admonishes him to “Wear this, for your mother’s sake.”

The inn, yard, corral and peasant hut were constructed on a backlot hill (now the site of a studio tour rest stop) around a deeply rutted old wagon trail. A large wooden cross, jutting from the brow of the hill, and other Old World props lend versimilitude to the setting. There are other glass shots of the castle and the coach in the mountains and an excellent miniature of Castle Dracula perched atop the crags. The camera roams the ruined cellars, where rats, armadillos and other animals scurry among skeletons and debris. There are several coffins. The lid of one raises slightly and a man’s hand snakes forth. The hands of women emerge from three other coffins and a gigantic beetle crawls out of another. Then Dracula and his wives are shown standing majestically beside their coffins. (In the Spanish version a heavy mist spreads from each opened coffin, followed by a pillar of light, then by the standing figure of the vampire).

Subsequent night-for-night scenes, representing the midnight meeting point in Borgo Pass, were photographed at a mountainous junction in the west part of the lot. These unreal but eerily effective shots are backlit from below, the light beaming up through the mist, presumably from a town in the valley.

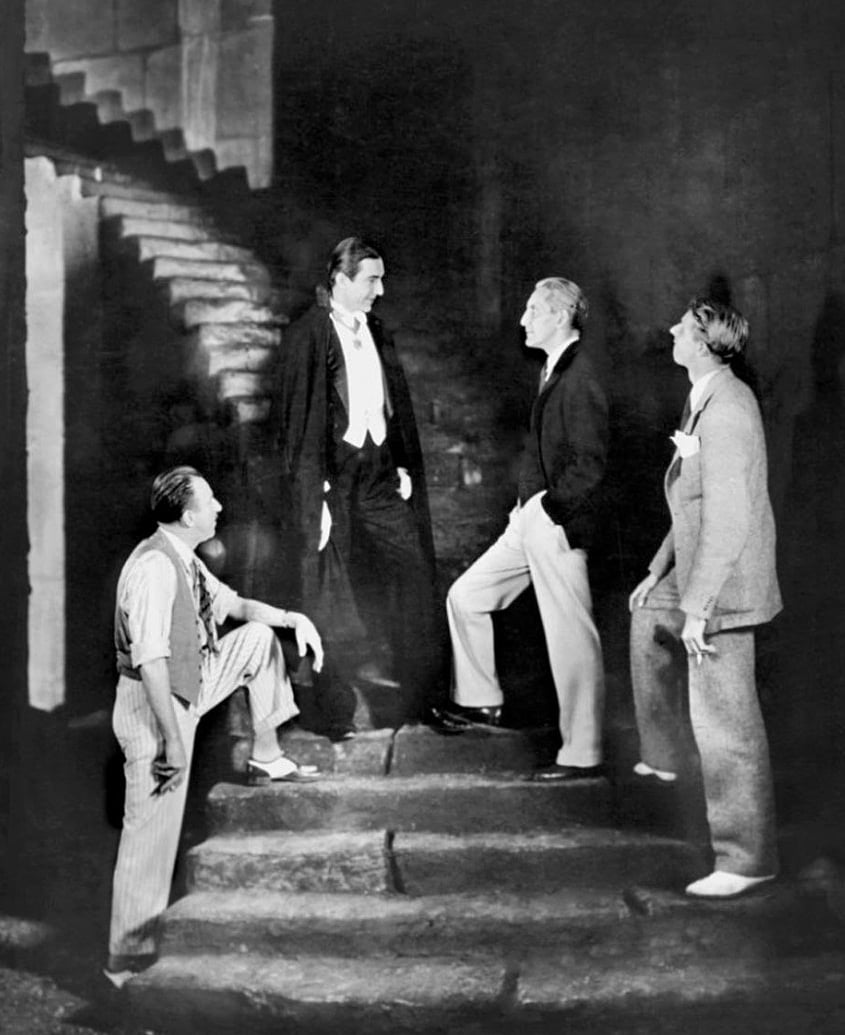

Renfield is all but dumped in the road as the driver hurries away. The closed carriage from the castle awaits. The driver is a silent man in black recognizable as Dracula himself. Renfield boards and is whisked roughly away. He tries to speak to the driver, but the seat is empty. A large bat flaps along between the heads of the horses. Debarking at the castle, Renfield is unable to find the driver. The massive doors of the castle swing open and Renfield enters, appalled to find the great hall in ruins. A voice announces, “I am Dracula,” and Renfield looks up the huge stairway to see his smiling host, formally attired, standing in front of a huge spider web. Wolves howl outside. “Listen to them!” says Dracula enthusiastically. “Children of the night. What music they make!” He bids Renfield to follow and the Englishman is startled to discover that Dracula has moved beyond the unbroken web, which spans the width of the staircase. As Renfield hacks through with his cane, Dracula notes, “The spider, spinning his web for the unwary fly. The blood is the life, Mr. Renfield.”

Renfield is ushered to a large, cheerful room where a meal awaits him. It is shown that Renfield is a realtor from London who has been asked to come secretly bearing a lease to Carfax Abbey in Whitby. When Renfield accidentally cuts his finger on a paper clip, Dracula is transfixed by the sight of blood and approaches menacingly. The crucifix drops out upon Renfield’s hand and Dracula steps back, covering his eyes. He then offers Renfield a bottle of “very old wine,” but doesn't partake with him because “I never drink... wine.” After Dracula departs, Renfield, drugged, stumbles to the terrace window, where he is halted by a large bat that emerges from a wall of fog. As Renfield collapses, Dracula’s wives enter and approach wolfishly, but they are driven back by a silent command from Dracula. At the fade, as fog engulfs the room, Dracula bends toward his fallen guest.

The journey to the castle is handsomely photographed, particularly in a stunning pit shot as the team and carriage hurtle over the camera in a thunderous roar and vanish into the castle grounds. The vaulted hall is introduced in a glass shot that expands the impressive set to enormous proportions. It perfectly conveys decaying grandeur and an atmosphere of dread. A fallen tree thrusts its branches through tall windows, bats flutter and screech beyond breaks in the walls, and the place is littered with fallen stones, decaying tapestries, cobwebs and dust. The deep shadows and some scurrying sounds suggest unseen menace at every hand. The “cheerful” bedroom is also large, with a fireplace of heroic proportions, windows that extend above the frame, ornate pillars and massive furnishings. This room is exploited to better effect in the Spanish film, in which the camera and players move more freely and the flaming fireplace becomes more than a backdrop.

In the hold of the sailing bark Vesta, bound for England through a terrible storm, an obviously insane Renfield crouches beside one of three large boxes and hisses, “Master, the sun is gone.” He cowers and pleads as Dracula stands over him: “You will keep your promise, master? When we get to England I’ll have lives — not human lives, but small ones, with blood in them.” One morning, at the dock at Whitby, officials come aboard the derelict vessel which has mysteriously arrived during the night. All the crewmen are dead or missing and the dead captain is lashed to the wheel. Hearing crazed laughter from the hold, they open the hatch and see Renfield staring up at them. A newspaper item tells that the only survivor of the ship, a madman with an insatiable desire to eat flies and insects, has been placed in Dr. Seward’s sanitarium at Whitby.

The Vesta is depicted first as a miniature. Full-scale shots of the seamen fighting to keep the ship afloat are undercranked, suggesting that they are footage from a silent film. The investigation of the derelict is imaginatively executed, the camera roving over the deck, taking in the details as the voices of the unseen men come over. In Browning’s version, the director himself bends into the scene to open the hatch. The scene gunning down at Renfield is quite subtle: the madman’s shadow produces an illusion that he has additional arms jutting from his lower body, lending him an appropriate insect-like appearance.

Dracula next is seen in an opera cape and top hat, striding by night through a foggy London street. His eyes fix hypnotically upon a girl selling flowers, then he draws her into a dark corner. Later, he enters a concert hall where a performance of the London Symphony is in progress. Placing a hostess under hypnosis, he sends her to Dr. Seward’s box with a message that he is wanted on the telephone. With Seward are his daughter, Mina (Eva), her fiance, John (Juan) and their friend, Lucy (Lucia) Weston. Pretending to have overheard the name of Seward, he introduces himself and explains that he has leased Carfax Abbey, which lies adjacent to the sanitarium. Although it is virtually in ruins, he says he will make few repairs because “It reminds me of the broken battlements of my own castle in Transylvania.”

Lucy, who is attracted to him immediately, is reminded of an old toast, “Lofty timbers, the walls around are bare, echoing to our laughter as though the dead were there. Quaff a cup to the dead already, hooray for the next to die!’ Dracula, betraying a rapturous longing, cries, “To die — to be really dead! That must be glorious! There are far worse things awaiting man than death.” The interior of Albert Hall, incidentally, is the famed “Phantom” Stage 28, which was built some years earlier for The Phantom of the Opera.

Lucy stays the night with the Sewards. Dracula watches her upstairs window as she prepares for bed. Soon a bat appears at the window; a moment later, Dracula approaches her bed. Fade in on an operating room, where Seward and his colleagues are unable to save Lucy from dying of “an unnatural loss of blood which we have been powerless to check. And on the throat of each victim the same two marks.”

Crane shots of the sanitarium grounds follow. Screams are heard from an upstairs room and the camera moves up to peer in as Martin, an orderly, confiscates a spider from Renfield and upbraids him for eating flies. “Who wants to eat flies... when I can get nice, fat spiders?” Renfield snarls.

Professor Van Helsing, a wise but unorthodox physician, has been brought from the Netherlands by Seward to investigate the strange deaths. Analyzing blood samples, he announces that “we are dealing with the undead. Yes, nosferatu, the undead — vampires.” He suspects that Renfield is the mortal slave of a vampire. To Seward’s objections, he replies that “the superstition of yesterday can become the scientific reality of today.”

In his moments of sanity, Renfield begs to be sent away because his outbursts might give Mina “bad dreams.” A wolfish howling is heard by night; Van Helsing believes it is the vampire communicating with Renfield. Dracula preys upon Mina that night. The next day, Mina tells of her “nightmare.” “The room seemed to fill with fog... Then two red eyes... a white, livid face... It came closer, closer; then the lips touched me.” Van Helsing discovers the mark of the vampire on Mina’s throat. After dinner Dracula comes calling, recognizing Van Helsing as “A most distinguished scientist, whose name we know even in the wilds of Transylvania.” Suspicious, Van Helsing tricks Dracula into looking into a concealed mirror. Dracula, livid with rage, makes a hasty apology and leaves through the French windows. A wolf is seen running across the lawn — Dracula, Van Helsing explains. Mina steals outside and is again victimized by Dracula.

A policeman, patrolling near a cemetery, hears a crying child and sees the white-shrouded figure of a woman disappearing into the darkness. Newspapers tell of a mysterious woman in white who attacks children, wounding them in the neck. Mina confesses that she has seen Lucy since her death and that “She looked like a hungry animal — a wolf.” Van Helsing promises that he will free Lucy from Dracula’s curse. Renfield reveals that Dracula has promised him “rats — thousands, millions of them, all filled with blood” in return for his obedience. Dracula returns and reveals to Van Helsing that Mina is lost “My blood now flows through her veins.” He tries to overcome Van Helsing, but is driven away by a crucifix.

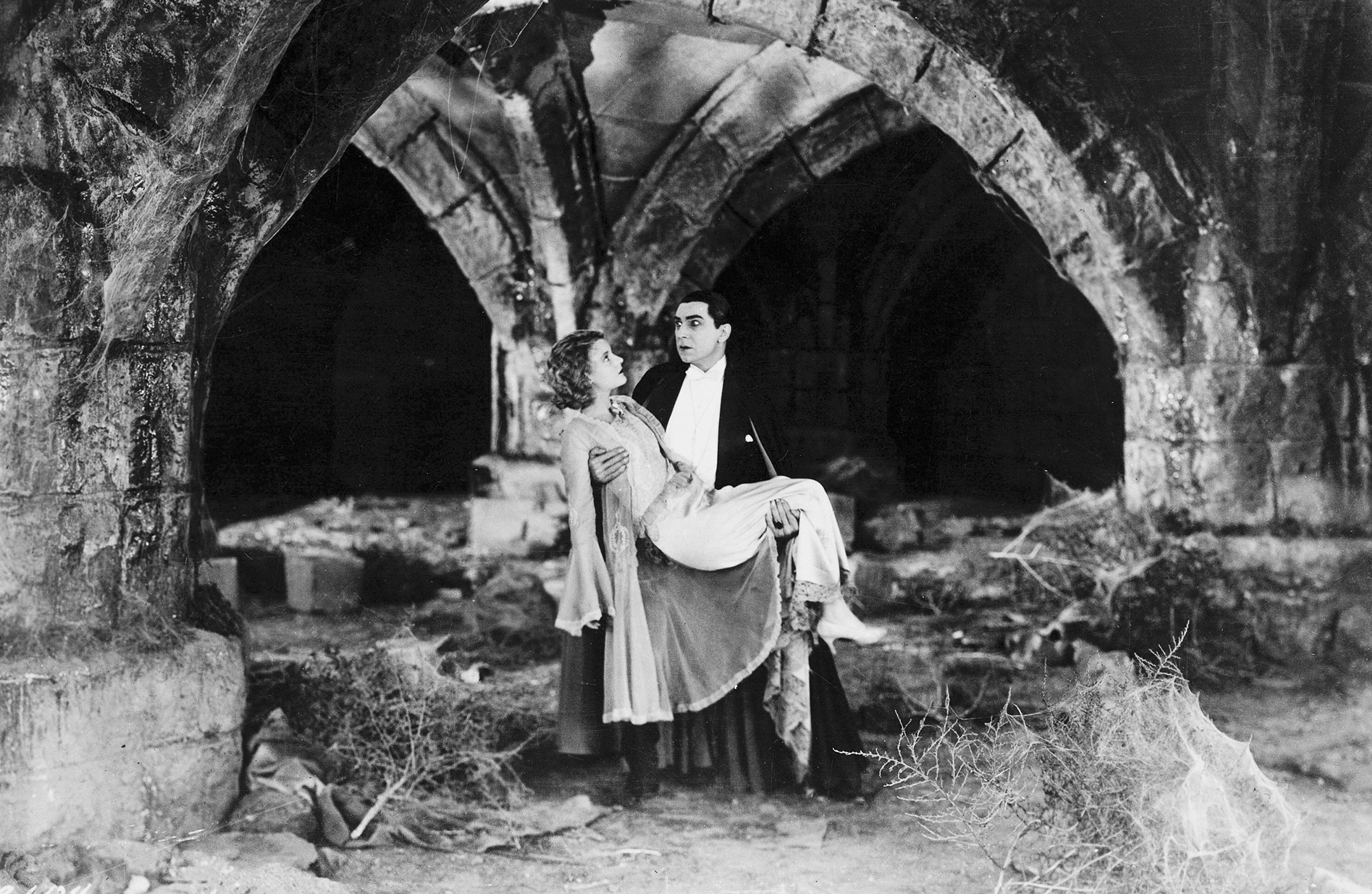

Mina tries to attack John, but Van Helsing halts her with the cross. She admits that Dracula made her drink his blood and she is now his slave. Later, as Mina sleeps, Dracula hypnotizes her nurse and causes her to remove the wolfbane that protects Mina. Dracula carries Mina away.

The scenes inside the sanitarium are photographed straightforwardly in rather long takes, showing little of the imagination that distinguishes the Transylvanian action. The action proceeds in the manner of a stage play, with some key material happening off-screen (the werewolf episode, for example). The feeling that great opportunities have been missed is inescapable. It is generally believed that Browning had to hurry through this part of the picture because he had fallen so far behind schedule. The several exterior scenes, however, are fascinating because of excellent night for night lighting and fog effects.

The Melford/Robinson sequences are better visually, being made up of a greater variety of shots. The sets are decorated more colorfully for the Latin audience, with added frills and filagrees, and the lace negligees worn by Tovar and Guerrero are considerably more eye-catching than the more British nightwear of Chandler and Dade. The one thing lacking is the magical ensemble work that Lugosi, Frye and Van Sloan gave to Browning.

The climax occurs in Carfax Abbey, a magnificently decadent setting, and in these scenes, much of the excitement of the opening reels is regained. Although the elaborate camera moves that were a Freund hallmark are absent in the English version, the lighting of the catacombs and a huge vault with a long, curving, unbalustraded stairway show artistry of a high order. Here again, however, Melford and Robinson take the palm for some stunning camera moves, especially when they utilize the unique “Broadway Crane” to carry the action onto the high stairs.

Renfield escapes from the sanitarium and goes to the abbey, followed by Van Helsing and John. Dracula angrily lifts Renfield by the throat and hurls him down the stair. Escaping his pursuers, Dracula flees to the catacombs below. Finding the coffins at dawn, Van Helsing opens one to reveal the helpless Dracula. The second casket proves to be empty and John goes searching for Mina. When Van Helsing destroys Dracula, Mina feels his death agonies, but as Dracula dies she is freed from his curse. Mina and John ascend the stairs as distant church bells ring.

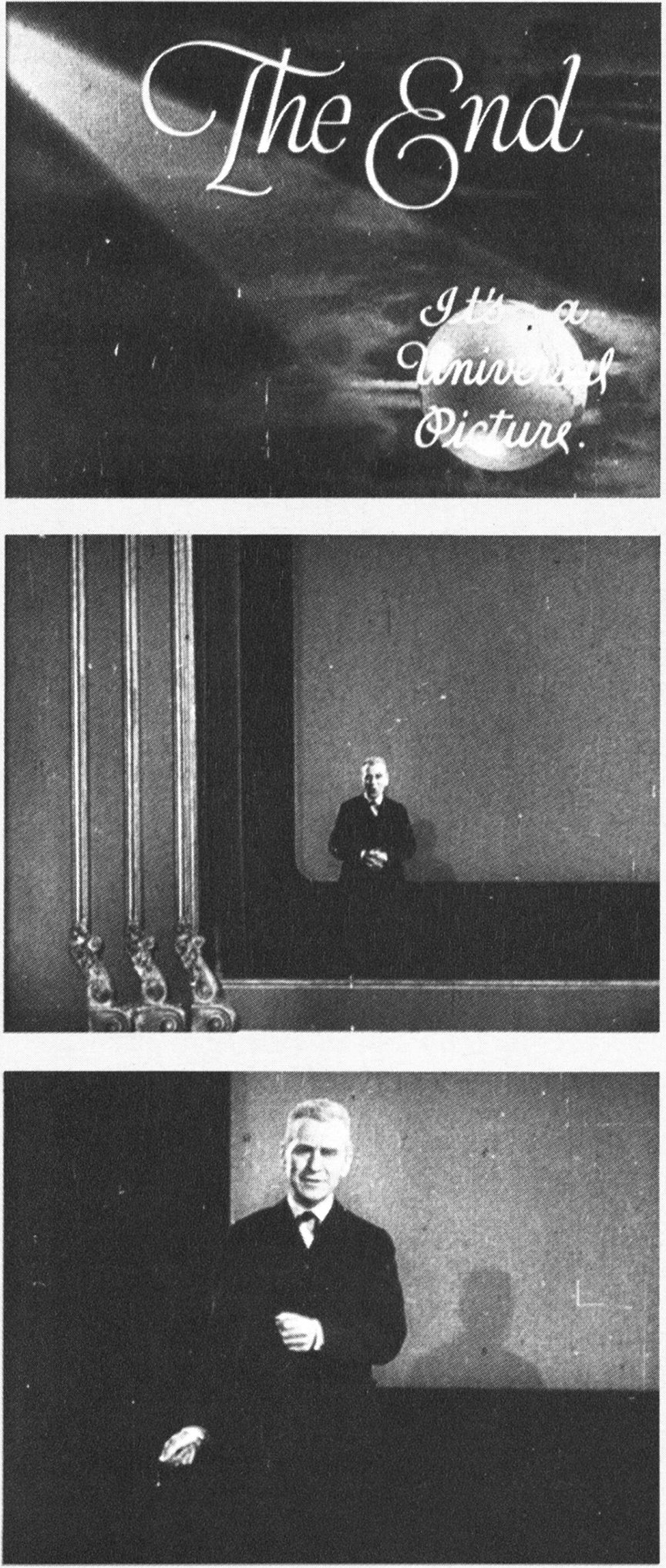

In the original release prints, the end title was interrupted as Van Helsing stepped in front of the screen to make a brief curtain speech:

“Please! One moment before you go. We hope the memories of Dracula won't give you bad dreams, so just a word of assurance. When you go home tonight and lights have been turned out and you’re afraid to look behind the curtains and you dread to see a face at the window — why, just pull yourselves together and remember that, after all, there are such things.”

The speech is taken from the New York play, in which it was spoken by Dracula.

The picture was photographed in full silent frame aperture for Vitaphone sound-on-disc presentation and for a subtitled silent version with intercut dialogue titles. When the sound-on-film prints were made (the Vitaphone was rapidly becoming obsolete) the picture area was masked to Western Electric standards to allow for the soundtrack and some masking at the top and bottom. This operation shifted the optical center and changed the compositions noticeably. The visuals gain considerably when seen at full aperture.

The Spanish Drácula was previewed early in January at the studio. The Hollywood Filmograph (January 10) stated that “If the English version of Dracula, directed by Tod Browning, is as good as the Spanish version, why the Big U haven’t a thing in the world to worry about... The other evening, before a capacity theatre on the lot, there was screened a preview ...which was witnessed by Bela Lugosi... and to use his own words the Spanish picture was ‘beautiful, great, splendid.’”

The English Dracula was announced to open at the Roxy on Friday, February 13, and go into national release the next day. Browning, pleading that he was “born superstitious,” telegraphed his objections to the equally impressionable Rothafel, who promptly changed the date to the February 14.

The Van Helsing epilogue, for reasons unknown, was removed when the picture was reissued in 1936. At this time, the Production Code Administration, which had become much more strict in the meantime, was unable to find anything visual that was deemed censorable. However, two cuts in the soundtrack were demanded: Renfield’s shrieks when he is being strangled by Dracula, and Dracula’s piteous cries (from off-screen) while Van Helsing is pounding the stake through his heart.

Universal recently had the English edition restored by YCM Laboratory in Burbank. The original negative was so badly worn as to be useless, according to technician Peter Comandini, but a new neg was struck from a 1930 lavendar protection print and the original frame ratio was restored. The censored bits from the soundtrack were found at the British Film Institute and placed in the new track, which was improved enormously by the use of the Impact Noise Reduction system. The curtain speech was found in fragmentary condition and has proved thus far to be unreproducible. Restoration is complicated because the scene was photographed as a fast dolly-in shot.

Although it seems a bit of a museum piece today, Dracula has some enduring and endearing qualities. Not the least of these is the performance of Lugosi, whose extravagant acting style and distinctively phrased, heavily accented delivery fit the role to perfection. Similarly, Van Sloan (of the stage play) and Frye are indelibly linked to their roles. David Manners does well by the Juvenile role and Helen Chandler makes a nice transition from ingenue to apprentice vampire. Bunston — also from the play — is fine as the harried doctor. Freund’s photographic style — which achieves a misty poetry at times and sets a trend by its emphasis upon Lugosi's eyes — still evokes an uncanny atmosphere. The settings could hardly be improved upon.

Its only music is an abridgment of Scene One of Tchaikowski’s “Swan Lake” during the titles, and (at the concert) bits of Wagner’s “Der Meistersinger,” Schubert’s “Rosamunde” and his Eighth Symphony. Most present-day viewers are critical of the lack of any background music, but audiences in 1931 felt differently. After years of watching silent movies with musical accompaniment, many filmgoers believed that such music was old-fashioned and constituted an intrusion upon the natural sounds and dialogue of the new talkies. In this context, the long silent sequences which occur through much of the picture are daring and effective.

And what of the Spanish version? An incomplete print exists at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Even with a full reel missing it is considerably longer than the English edition. A complete print in the Cuban Film Archive is listed at 102 minutes — a full 27 minutes longer than the standard version. It’s easy to agree with the El Cine Español critic Fillipe Veracoechea, who said in 1931 that “Spanish-American audiences will receive Dracula as the most fascinating picture made.”

There was only one squawk from the audiences: the clash of different dialects spoken by actors who hailed variously from Spain, Mexico, and Central and South America.

In 1992, the Spanish-language Drácula was revived and released to wide acclaim. In 2015, the Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” The complete film can be watched here.

Browning’s picture was added to the National Film Registry in 2000.

For more on the classic Universal Monster films, we offer this piece on the man behind the makeup: Jack Pierce — Forgotten Make-up Genius.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.