The Whale Plumbs Deep Water

Matthew Libatique, ASC, LPS trades stylization for simplicity in Darren Aronofsky’s poignant study of a damaged soul.

The Whale is a dark — and heavy — film. The first time we meet the story’s central character, Charlie (played by Brendan Fraser, in ample prosthetics), he’s teaching a remote class on literary composition, represented onscreen by a black window in the center of a matrix of glowing, windowed faces. He claims his webcam is broken.

The next scene takes place on an overcast day, in the dim front room of Charlie’s untidy apartment. The camera tracks left in an arc from the open kitchen into a connected living room — revealing the back of the couch upon which Charlie sits, panting — then pans right against the move as it comes around an end table and table lamp next to the couch, revealing a laptop on a stand with a gay pornographic film on its screen, and finally all 600 pounds of him hanging off the side of the couch. A moment later, he nearly has a heart attack.

Charlie is morbidly obese and in the final stages of heart failure. He refuses to check into a hospital, giving himself one week to live, and over the next four days, others — his estranged and very angry teenage daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink), his nurse (Hong Chau), a young missionary (Ty Simpkins), his alcoholic ex-wife Mary (Samantha Morton), and the briefly glimpsed Dan the Pizza Man (Sathya Sridharan) — will enter into orbit around his massive black hole of despair, from whose inexorable gravity a ray of light is striving to break free.

Mood and Movement

The movie reteamed Matthew Libatique, ASC, LPS with his longtime collaborator, director Darren Aronofsky. Based on the stage play by Samuel D. Hunter, who also wrote the screenplay, The Whale entered production just as the filmmakers themselves emerged from 2021’s Covid lockdowns. “It was the first film either of us had done since the pandemic started,” says Libatique. “Darren had the idea to make it with a small crew, on one set, in a controlled environment. A lot about the way we did this project was informed by the times, and in a weird way, it freed us up to not put so much pressure on ourselves.”

With just three weeks of prep time, Libatique was first tasked with finding the film’s mood. “I put together a bunch of reference stills for Darren like we used to do back in the days of Requiem for a Dream (AC Oct. ’00) and The Fountain (AC Nov. ’06), but I found it hard to communicate to him what I was thinking for this one. So, we pivoted to relying on our intentions — which is what we’ve always succeeded at anyway.

“From a cinematographic standpoint, I wanted to give the actors a place that felt real. Darren wanted to let them move and push the camera blocking into different angles so that it wouldn’t get static — even though Charlie is this static figure.”

By the second week of prep, Aronofsky was running scenes with his actors on a taped-out set built within Umbra Stages in Newburgh, N.Y. Libatique likens the process to that of Black Swan: “Whereas with that film we spent a lot of time rehearsing the ballet choreography, on The Whale we were rehearsing the words from the play.”

As they had on mother! (AC Nov. ’17), the filmmakers made video recordings of all the rehearsals. Libatique explains, “In that film, the language of moving the camera needed a proof of concept, but this time we did it more to see how the actors’ blocking worked in our space, which informed how we would move the camera. We normally plan out everything — shot lists, overhead diagrams, lighting diagrams — but this time it was more about reacting in real time to what was happening in front of us.”

According to the cinematographer, “the play is very spartan, and as cinema goes, so is the film.” In adapting The Whale for the screen, he and Aronofsky leaned into its theatrical qualities, setting up wide masters to cover a scene from beginning to end, while still making the imagery cinematic through the use of camera movement, light and mood.

Framing, Gear and Grain

“We concentrated more on our framing than any technical aspect of the camera,” says Libatique. “Shooting in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio was an early decision. The character of Charlie was going to spend a lot of time sitting on the couch with people standing around him, so we went for verticality versus a more horizontal frame.”

The Whale was photographed in full-frame 6K on the Sony Venice, with Angénieux Optimo Prime lenses. Libatique had worked with Venice cameras before — on commercials and then a short film for director Olivia Wilde — but The Whale would be his first feature using one, and Aronofsky’s first feature not shot on film.

Libatique planned to light the film at extremely low levels, which led him to explore working with the Venice at its High ISO setting of 2,500. “It just seemed like the right tool for working at more realistic light levels,” he says.

“Optically, I was after soft falloff,” adds the cinematographer, who prefers to work at “a pretty wide-open stop, between T1.8 and T2.5.” The result is a portrait-like depth of field for the close-ups, most of which were shot close to the actor at a focal length of 50mm.

“I also used a device from Camtec called a Color-Con, which is a filter that has a series of single-emitter LEDs embedded on all four sides,” he says. “I used it in combination with a ⅛ Tiffen Glimmerglass, which essentially flashed the image. The color of the LEDs would change slightly based on the base color temperature of the scene.”

Having shot six of Aronofsky’s previous features, Libatique has a strong sense of the director’s expectations. “One of the things Darren loves about shooting film is film grain,” he remarks. Libatique successfully pitched the idea of using LiveGrain, a real-time texturing tool that replicates the three-dimensional texture of motion-picture film by mapping the complete range of a film stock’s exposures and colors to a digital image. LiveGrain was incorporated into a shooting LUT for The Whale based on the look developed by DIT Jeff Flohr for Money Monster (shot by Libatique on an Arri Alexa XT) and was also employed for dailies.

The Stage Is the Set

As Libatique observed the actors rehearsing with Aronofsky, he realized that “the key to moving the camera was how Darren moved the actors.” The way the characters enter a scene, interact with Charlie or each other, move about the set, engage in “business” and exit has the constant rhythm of a stage play. Libatique’s camera floats through these scenes using point-of-view shots and motivated camera moves to establish new eyelines and triangulate the actors’ positions in three-dimensional space.

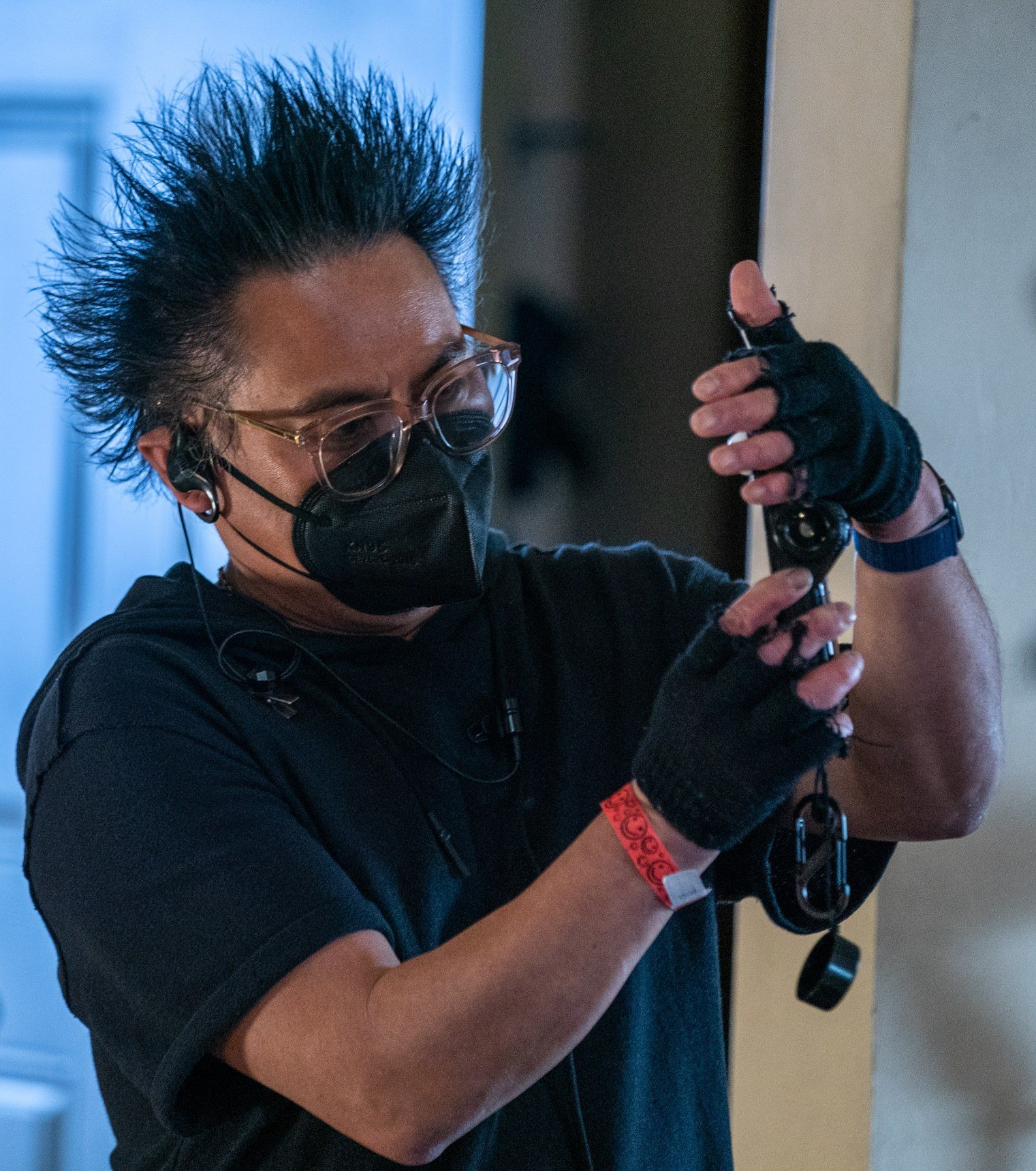

Libatique operated remotely, shooting the entire film with the camera mounted on a Ronin 2 gimbal at the end of an Aero Jib, sometimes from a Fisher 10 dolly. “We did it that way so we could get the actors’ eyelines closer to the camera,” he says. “Also, there wouldn’t be another body on the set to distract them.

“Originally, the idea of the jib and gimbal was another Covid-related precaution,” he adds. “Our thinking was that there would be fewer people surrounding the unmasked actors in this small space. However, we soon realized the added value of being able to achieve tighter eyelines, which is always an obsession for Darren. Without me right there operating the camera, the actors could look at each other and achieve the desired eyeline.”

Going Light on Light

Hewing to his intention of creating a space that felt real for the actors, Libatique wanted his lighting to blend in with the work of production designers Mark Friedberg and Robert Pyzocha. Even though the set’s walls and ceilings were designed to be removed, he decided to light almost entirely from the floor, leaving pockets of darkness between the sources.

“It’s been a philosophy of mine to give actors the space to give an amazing performance, which means not being too precious with light,” he says. “I learned that a long time ago, on Requiem for a Dream. We had Jared Leto and Jennifer Connelly on this jetty out in Coney Island, we were losing light, and I was trying to use a 4'x8' beadboard to get some light into Jared’s eyes. He turned to me and said, ‘Is there any way we can go without that?’ I asked why. He said, ‘I just don’t want to see it.’ Then he motioned toward the ocean and said, ‘I’d rather look at all that.’ So, I took it away. I’ve always remembered that.”

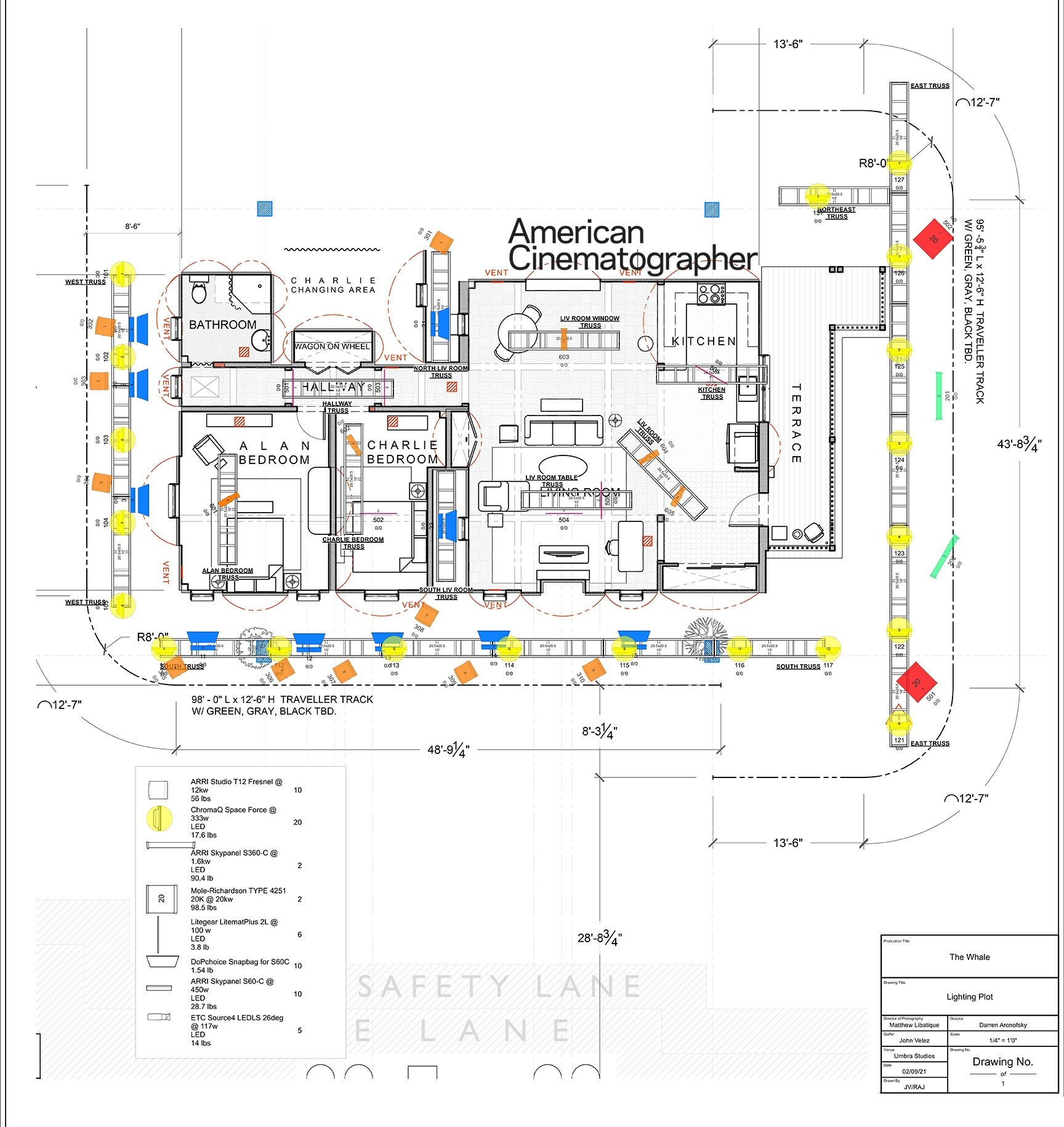

The high sensitivity of the Venice allowed Libatique and gaffer John Velez to effectively employ household units, Astera tubes and small, well-placed bounces instead of more traditional lighting tools. “The set windows didn’t really accommodate much daylight, so I relied on interior practicals and small covered wagons of Astera NYX bulbs diffused with Magic Cloth, light grid or opal,” he says. “Sometimes we used Astera tubes in the ceiling, wrapped in Magic Cloth or 250 diffusion, and a smattering of LiteMat Spectrums. Our biggest interior light was a Hudson Spider.

The production also employed an array of Astera Helios and Titan tubes rigged into the set’s ceiling with a teabag of Magic Cloth. Libatique explains, “This was less to light faces and more to ensure background separation as actors move into the spaces in between light. From the floor, we augmented the two hero practicals that bookended Charlie’s couch with ‘covered wagons,’ small baton-style rigs with a frame to allow for a change in diffusion. We place these on the floor near the practicals to create warm edges, and on occasion, they served as the key light. This was the foundation of our light strategy, but we would augment our singles with Lite Gear Spectrum 4s or a Hudson Mozzie. Exterior lighting was mainly provided by Arri SkyPanel S60s and 360s, with Fiilex Quads and Q8s to backlight the ‘rain’ we created.”

Darker and Brighter Days

Production on The Whale lasted 25 days in Newburgh, with one exterior day in New Paltz. The story is marked by days of the week, starting with a dark and rainy Monday. Tuesday and Wednesday are overcast, Thursday sees rain again, and the final day, Friday, is sunny. Libatique says that the production intended to shoot in chronological order, “but by the second day, we realized that wasn’t going to happen. Almost every movie deals with those kinds of realities.

“It can take a while, even after you’ve started shooting, to really find the look of the movie,” he offers. “I don’t think I’ve ever nailed the look of any movie on day one. Not until all of the different factors fall into place does it really come together.”

He points to the film’s first scene, which was also the first to be filmed: “Typically, I think I tend to make the first scene too bright, but in this case I think I played it too dark. And it wasn’t an easy shot. In the middle of doing it we had to wild a wall, and we had to wild a table. We also had to wild a piece of the carpet, which we cut out and pulled back for our dolly grip, Brendan Lowry, as the camera started to wrap around.”

The grim, heavy mood of this scene stands in powerful contrast to the movie’s final sequence, which shows Charlie, bathed in sunlight, floating away. “The language of the light within the film was designed with the end of the film in mind,” Libatique notes. “In this last moment of Charlie’s life, there’s a reprise of an early scene, but this time Charlie is successful in standing up and walking to Ely, who is standing at the front door backlit by the bright sun. As Charlie approaches Ely, he courageously faces the sunlight.” Two 24K Arri Fresnels provided the “sun” on Charlie’s angle, with one spotted to Charlie and the other providing additional light in the room. For Charlie’s very last breath and the whiteout transition, “we used a combo of Solar Highbeams and Arri Orbiters bounced into the ceiling.”

Rolling With It

By the third day of production, everything was falling into place, including a key element: Charlie’s voluminous prosthetic makeup, designed by Adrien Morot. “Adrien worked with us on The Fountain, Black Swan and Noah, and one of the things I really like about his work is the way he puts color into prosthetic skin,” says Libatique. “We were in constant communication about the way the color of the light shifts from cool to warm from Monday to Friday, and on that front, I didn’t feel restricted in any way by the prosthetics. The language we created for the light was something that all of our keys were aware of, so Adrien and his team worked hard to prep the prosthetics in anticipation of the next day’s work. Adrien’s constant attention to detail made lighting a non-issue in terms of needing any added techniques.”

Nevertheless, a certain amount of attention to Fraser was required for camera resets, “because as he moved, sometimes the wardrobe or the prosthetic would fall out of place,” says Libatique. He and Aronofsky were already used to rolling through takes on film without cutting (“for momentum”), and found this approach even easier with digital, “so we would just keep rolling while Adrien’s people jumped in and worked on Brendan.”

Eyes on the Prize

The Whale was graded by Tim Stipan at Company 3, continuing a relationship with Libatique and Aronofsky that began on Black Swan (AC Dec. ’10). Once again, much of the work done in post was in service to the actors’ performances. For the cinematographer, “Eyes are critical. We’ll often draw windows around them to lift them up.”

Libatique recently wrapped an 8K re-grading of his and Aronofsky’s first film together, Pi (AC April ’98), also performed by Stipan at Company 3. “We were sitting in one of the best grading facilities in the business, and it really dawned on me that we made this movie for nothing,” Libatique muses. “Later, Darren and I were watching it together in New York, just reliving that time in our lives and feeling the energy of making an independent film.”

Even now, he adds, that feeling remains with him, regardless of a production’s scale. “I didn’t come up through the studio system — I came up through independent cinema, so doing something small isn’t a big stretch. Rather than lament what we don’t have, we just celebrate what we do.”

A Look Through Aronofsky’s Viewfinder

By Iain Marcks

Darren Aronofsky, director of The Whale, shares some of the creative philosophies and strategies he and his crew followed while making the movie.

Basics: “We spent about three weeks in prep and rehearsal. I’d spend those mornings blocking on set with the actors, and then Matty would come in after lunch to see what we’d come up with. In the second half of the day, Matty and I would discuss camera moves, which walls would have to fly away, things like that. This approach allowed us to take a smart, economical approach to making a low-budget movie with limited days, and it took our process back to the very basics of filmmaking, which are: lighting, camera placement and performance.”

Language: “Theater is very much like taking a slice out of a cake so you can look straight in and see inside, but with cinema, you can be in the cake. In establishing a visual language for The Whale, our big breakthrough came when production designers Mark Friedberg and Robert Pyzocha put Charlie’s couch in the middle of the room, because that put Charlie at the center of the set and allowed us to block the other actors around him, like satellites, which provided us with more opportunities for character development.”

Lighting: “I love the way Matty uses light to help tell the story and to support its themes. We spent a lot of time talking about the weather in the film, because that would affect our light in different ways. We took a big gamble with the concept that the film would move from a rainy, stormy look to this glorious, sunlit last day. And if you’re going to take a risk, you’d better pull it off.”

Camera: “One of the really interesting things we did was to mount our camera on a gimbal at the end of a jib arm, with Matty operating on wheels from the next room. Nothing replaces having an operator on the camera right next to the actors because a great operator can feel what an actor is going to do and adjust to it. But it was early in the pandemic, and I think doing it this way was a smart solution to keep everyone safe, even if it meant giving up a little bit of knowing what the character was going to do. Luckily for us, our main character didn’t move around a lot.”

Performances: “Our approach made the set a bit more intimate because the only people on set besides the actors were the boom op, someone on the jib arm, someone on the dolly, and me. It made the room very quiet, and I think that helped the performances. It also helped me get extremely close eyelines. The eyelines in a lot of my movies are really, really tight. I think it brings you deeper into an actor’s eyes if you can see both of them at the same time. It’s almost as if they’re looking at you.”

Collaboration: “Matty and I recently had the chance to screen an 8K remaster of Pi together in New York. It was an amazing experience and a lot of fun revisiting the energy and the excitement we had back then. Matty is truly one of the great collaborators of my life, and that collaboration has only gotten better over the years, as we both have become more experienced filmmakers and closer friends.”

Following there publication of this story, Libatique sat down with Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, ASC to discuss his work in The Whale (and Don't Worry Darling) in this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations: