Behind the Scenes with Thunderbirds

Why filming puppets for Britain’s very popular television series requires more time and care than the production of “live-action” with full-sized human players.

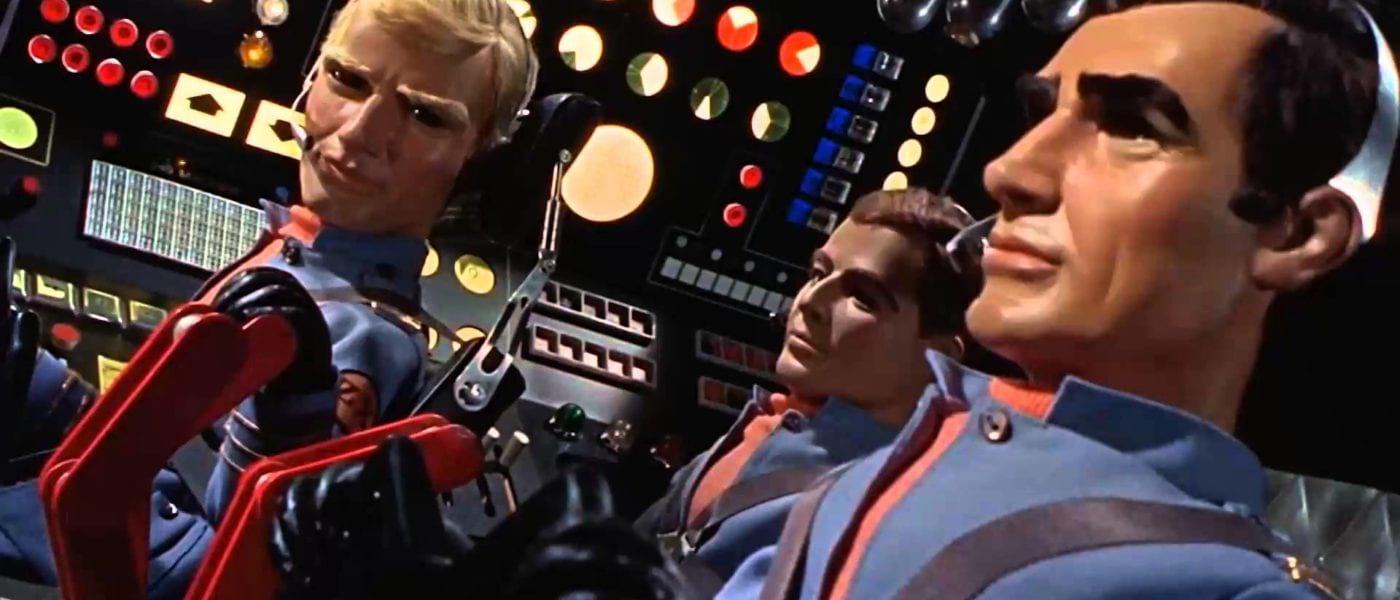

Every television viewer in the British Isles and a good many more thousands on the Continent of Europe, know the Thunderbirds and the many adventures of their “stars.” Now their makers, having just completed a cinema feature film in Techniscope and Technicolor, are rapidly building a world audience for them. “Lady Penelope” and her companions are friends of the family in millions of households; yet these “stars,” with their strongly established characters and characteristics, are things of plastic and fiberglass and leather and metal, puppets operated by strings from above in the traditional manner that has survived from the very earliest days of entertainment.

But in the studios of Century 21 Productions, traditional modes of operation are allied to techniques as forwardlooking as the mechanisms and environments of tomorrow in which the puppets have their being.

The start of it all was almost accidental, for the company was originally formed to make films in an orthodox way. Then came a demand from a sponsor to make a short puppet film, and a special aptitude for the technique was discovered among the small band of people who then comprised the company, particularly on the part of Gerry Anderson, today’s managing director of the group of companies of which Century 21 Productions is a part, and also on the part of his wife, Sylvia.

From this beginning grew the television series and ultimately the making of the United Artists color feature Thunderbirds are Go! which is drawing enthusiastic audiences in cinemas in many parts of the world.

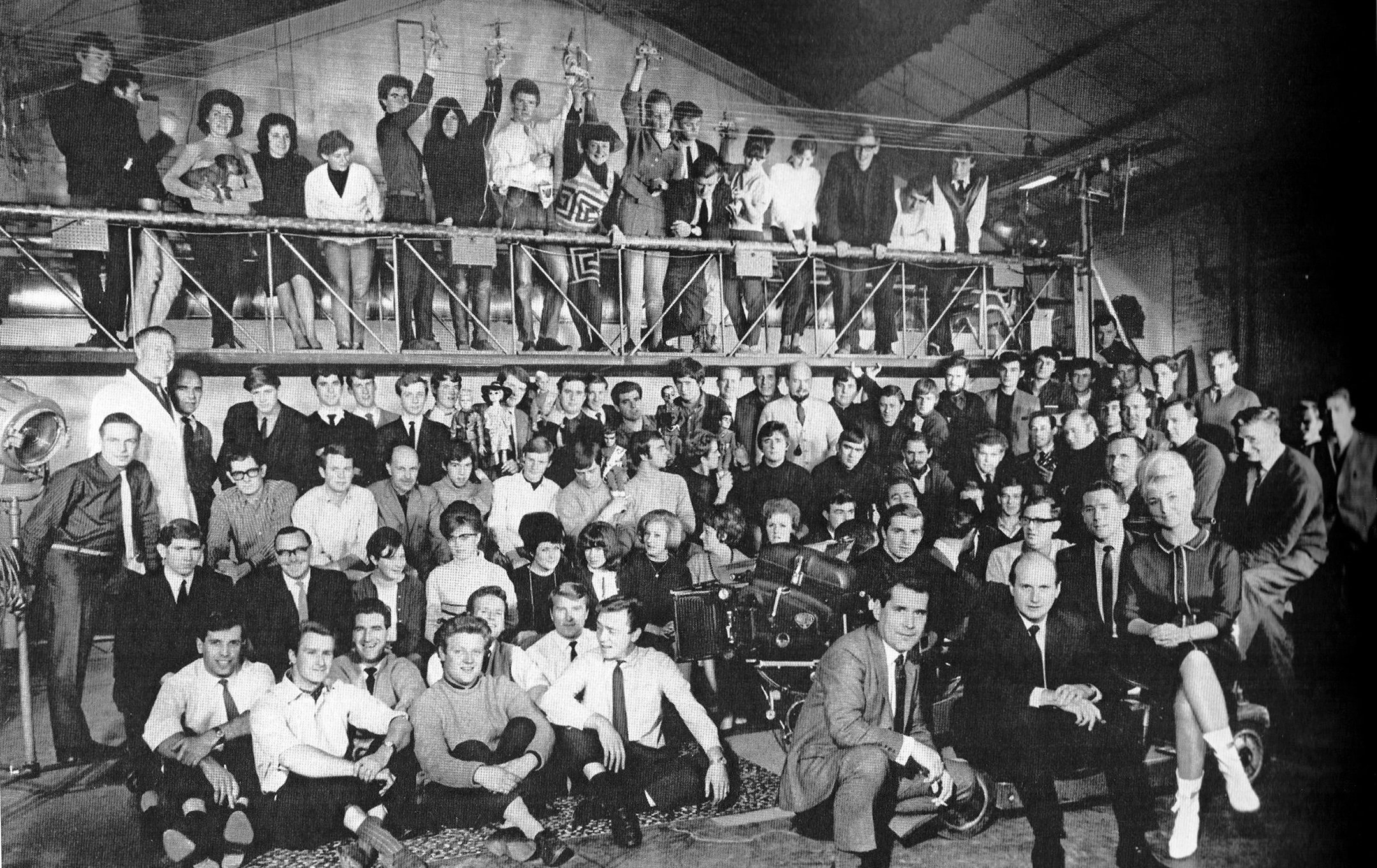

Starting in 1958, with small and modest premises in Maidenhead, Berkshire, the company has been forced by the continuous increase in the volume of work to make a series of moves, each time into larger premises, until today the studios and offices of Century 21 Productions and the other companies that together form Century 21 Productions Organization occupy several acres in the Slough Trading Estate in Buckinghamshire. During 1965, studio floor space was trebled. There are now seven stages and during the current year, work will proceed on another color feature film simultaneously with a new television series. Already there are plans for further expansion.

The atmosphere throughout the organization is terrific, a combination of ease and friendliness with an almost frightening level of efficiency and devotion to the task. This is largely due to the part played by the Andersons and their fellow directors, deputy managing director Reg Hill and director John Read, a benevolent despotism that stops short of carping criticism and interference, but which can provide knowledgeable guidance, advice or decision at every stage of a production at the drop of a hat. The personnel are aware that they are working for bosses who really know the job and who, at a pinch, could do many of their tasks.

Puppet film production, especially of the space-age type, demands even more pre-planning and organization than does “live-action” production. Meetings are held between the principals — the producer, the director and the various departmental heads — who will be concerned in the production.

The first consideration is to determine the character and characteristics of the “stars” and other artists. Sylvia plays a great part in character visualization and works closely with the director and the head of the puppet department, in choosing the personalities and appearances necessary to interpret the story. She also chooses the artists who will supply the voices of the various characters and directs the recordings of the dialogue at an early stage. The reason for this will become apparent later.

The art director also comes in at this time and sets, wardrobe, properties and many other requirements are decided upon. All of these, and in fact almost everything seen on the screen in the finished productions, will be made in one or other of the company's own workshops.

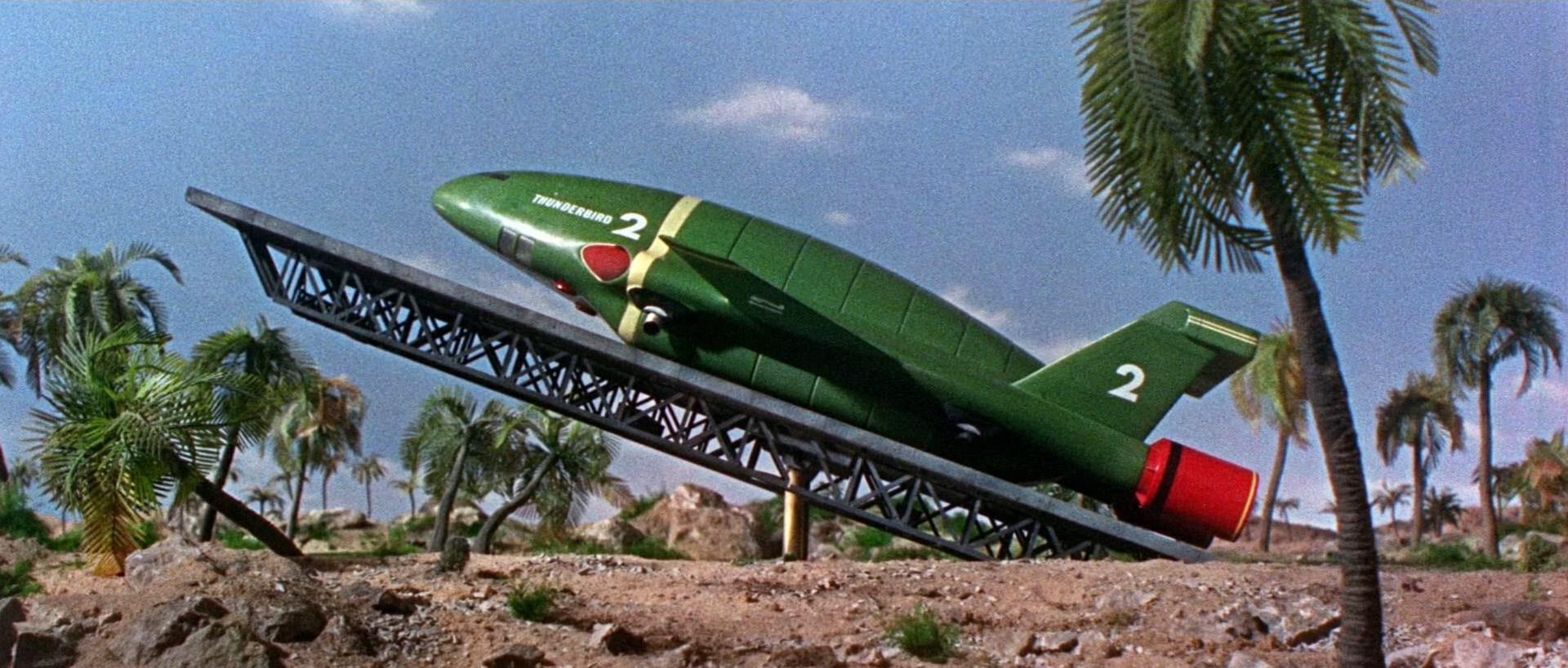

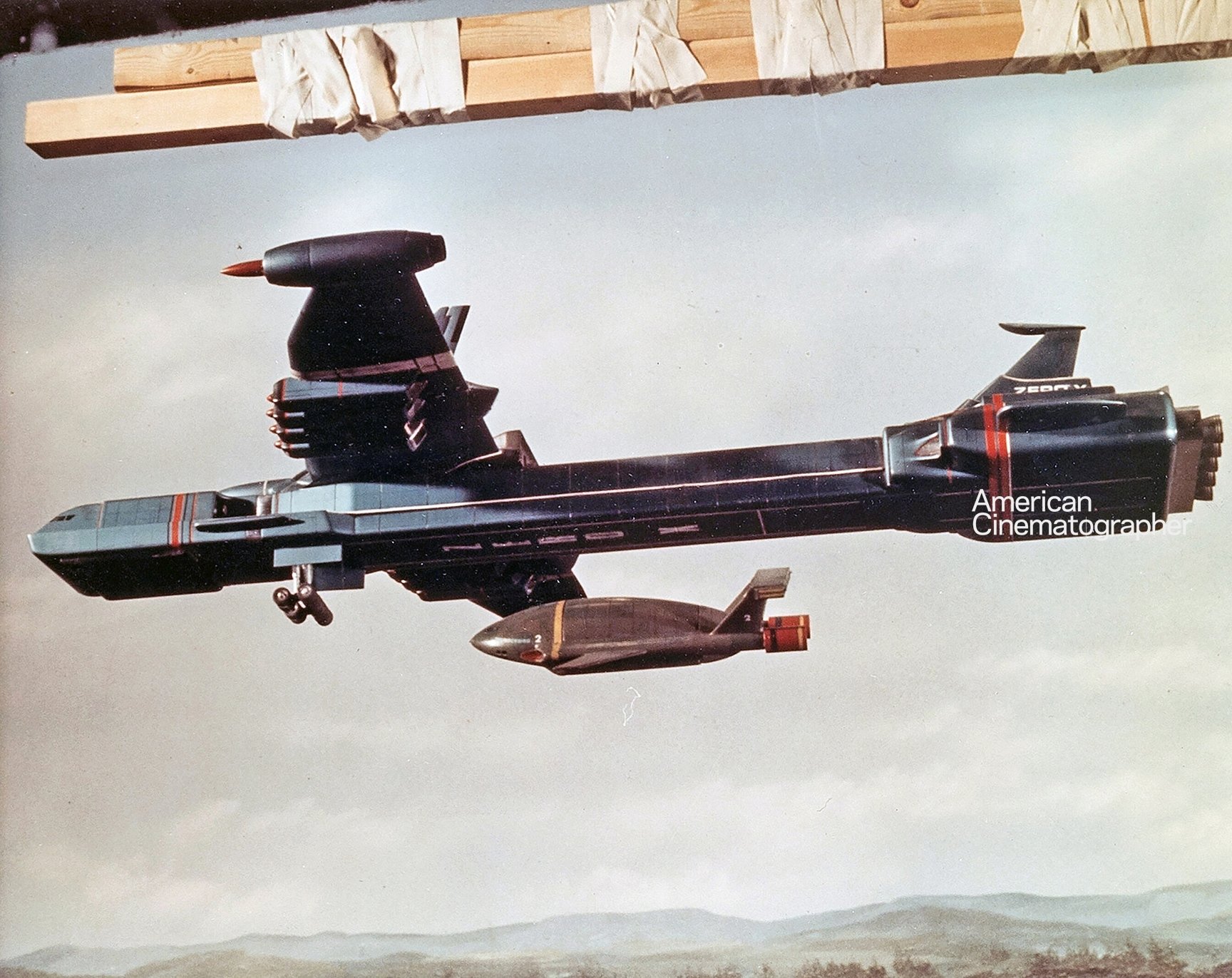

It should be made clear that a Thunderbirds production is composed of two different kinds of scenes, shot separately on different stages. There are the scenes in which the puppets appear, and the special effects scenes of spaceships and other vehicles in action, the “exteriors” as they might be termed, in which the puppets do not appear. The two are linked by shots of the puppets in environments that purport to be the interiors of the establishments, vehicles, and craft we have seen in the “exteriors.”

Among the production personnel, there are two puppet units and three special effects units. Special effects scenes occupy about one-third of the total screen time of an episode or a production.

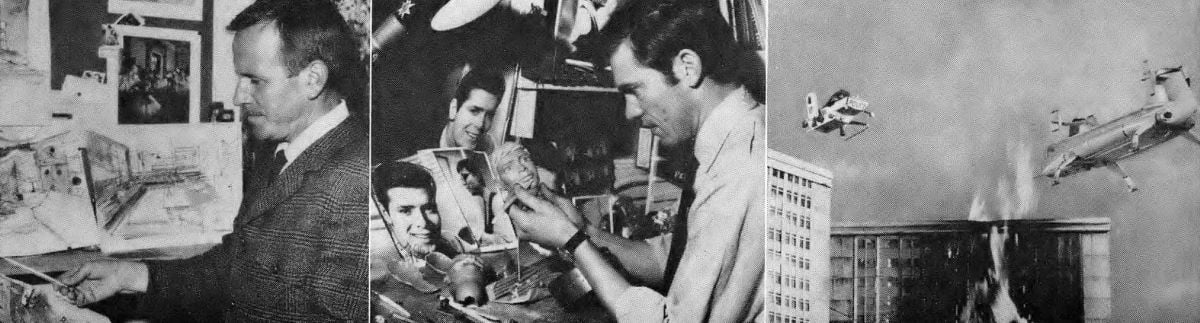

The director discusses with Derek Meddings, the supervising director of the special effects department, and with the artist-designer allotted to the production, the nature and character of the effects desired and how the happenings in the effects scenes will relate to the puppet scenes. The two groups are married on a storyboard, after which the artist designs the effects scenes and the space vehicles and other machines that will inhabit them. The productions greatly benefit from the almost fantastic imagination and originality of the young designers working under Meddings, who, at the same time, contrive to make their inventions credible from an engineering point of view.

Special-effects models are made to various scale sizes and incorporate different degrees of detail according to the nature of each scene and the distance of the model from the camera. Their complexity or simplicity will be determined by the work they are required to do.

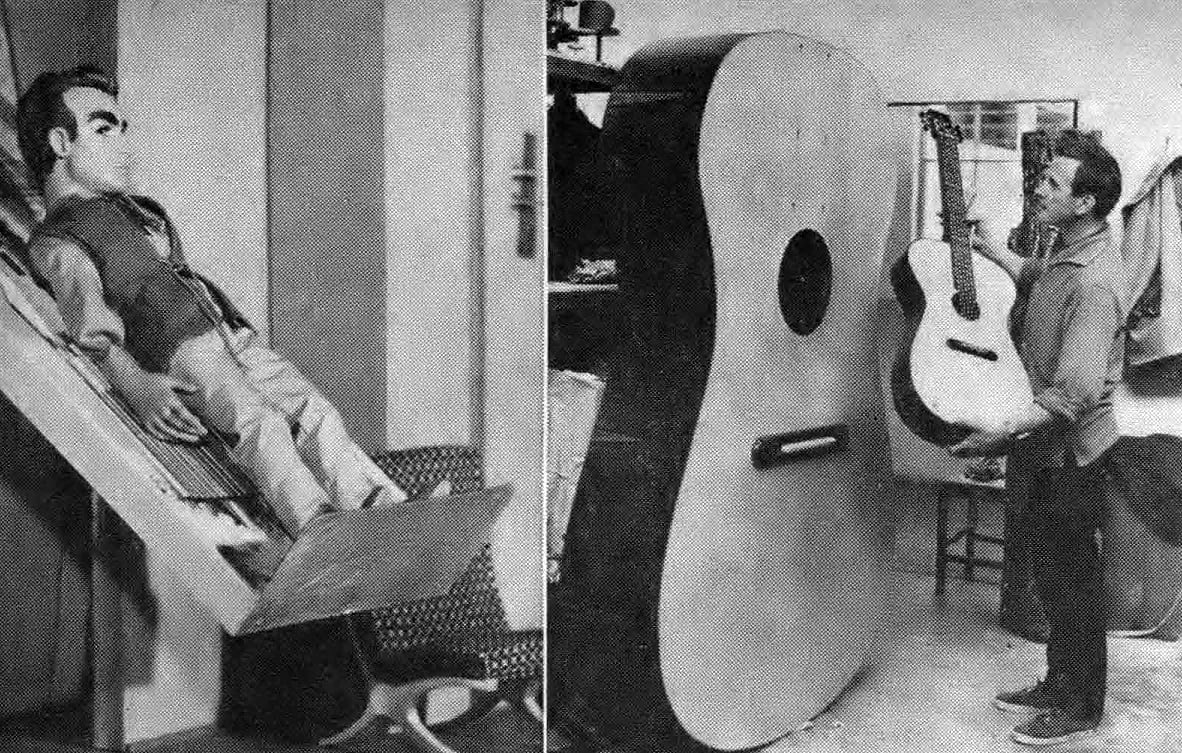

Puppets, on the other hand, always conform to a one-third human scale. This scale was originally arrived at almost fortuitously, but experience has shown that it is an almost perfect compromise between providing puppets that are of adequate size for accurate manipulation and control and having to engage in a costly building program to gain sufficient height in the studios to enable larger puppets to be used.

Supervising art director Bob Bell generally works on each episode for about a month before it is put on the floor. Set design is complicated by the fact that puppets, being operated from an overhead walkway or bridge, can only move backward and forwards along a straight line. To give them apparent flexibility of direction the whole set in which they appear must be mobile so that it can be moved in any desired direction and if necessary rotated during shooting.

There are a number of standard sets for each series; such as Lady Penelope's drawing room, Tracy's lounge, and the cockpits of Thunderbirds I, 2, 3, 4 and the Space Station. These are reverted from time to time during production and are kept intact until a series or production is completed.

For other sets some use is made of standard flats, but these are horizontal in shape, approximately 3' high by 6' long, and include stock door and window flats.

Many scenes are unorthodox in design and shape and appearance and have to be constructed in their entirety. Every kind of material is used to obtain the desired effects or to attain that close approximation to reality which has a strong pull of its own. Assistant art director Keith Wilson says “You have to develop a knack of finding things to suit and of adapting many things in common use to new purposes.”

Plain, colored, transparent and textured plastic sheetings are all employed to great effect. Balsa wood is used for “one-offs” of models, fiberglass for multiples or series. While model scales will range from one-tenth up to one-third life size, the trend nowadays is to build bigger sets and to use larger models and even more modern materials.

The studios are equipped with rolling roadway machines, with three horizontal moving sections representing a carriageway and two sidewalks, with a vertical backing behind them. All of these can each move independently in either direction at speeds ranging from 0' to 4' per second and can be stopped instantly.

A roller system carries a vertical sky backing of canvas about 9' high by 18' long which can also be moved in either direction and on which cloud patterns can be painted.

A towing machine has been made to the Company’s design that can be set to tow objects at a predetermined even speed.

The tiny model fighter planes for the Captain Scarlet series “fly” in front of an 80' long, 18' high cyclorama, which is lit with rows of tungsten-halogen floods. The aircraft are marvels of detail and precision. As are the many other mechanical models I saw. The cars and trucks have independent suspensions to give them smooth movement and dip their fronts when stopped, just like full-sized vehicles. Many of the models can be operated by remote control. Experiments have been carried out with a remote-controlled jet-propelled aircraft that will climb to a considerable height, perform aerobatics, fire machine guns, and emit black smoke.

Explosions are important in Thunderbirds stories and much research has been carried out to discover the best explosives. Cordtex has been found particularly suitable. As powerful as nitroglycerine, it comes in strips and sheets that can be cut to size and shape with a bronze knife or bronze scissors.

Technical gadgetry plays an important part in many scenes and much-specialized electrical, electronic, and mechanical knowledge is available to contribute to the design-one might almost call it invention-of mechanisms of a fantastic but highly convincing character, and to the construction of their almost jewel-like parts.

The appropriate department provides such accessories as a thruster pack to enable one of the characters to “fly;” model crash helmets and bone domes; guns and holsters. Most of these are to one-third scale, but sometimes they are made full size for use in live-action shots. Then, when a human hand has to come into the scene to operate a mechanism or control, it is made up to look like a puppet hand.

A prowl around the property store vividly suggests the travels of Gulliver. On shelf after shelf, carefully protected behind transparent plastic curtains on runners, are rows and rows of Lilliputian tea sets, lamps, candlesticks, bottles and glasses and jugs and a host of other bric-a-brac. In other parts of the store are period, modern and futuristic suites of furniture and odd pieces, and curtains and cushions and hangings and, on high, a model bandstand used recently with puppets representing Cliff Richards and The Shadows. The property master, Arthur Cripps, was an upholsterer before he took on his present job. He makes nearly every piece of furniture and the curtains and hangings and cushions and keeps everything in good repair ready for use at the shortest notice.

There is a section that I promptly dubbed the “dirty dogs department.” Working close to the stages these people ensure, by suitable scuffing and dirtying, that new models and properties acquire a properly used appearance before they are put on the set. They also do running repairs during production.

There is of course a department where all the costumes, both male and female, are designed and made. Sylvia Anderson designs most of the clothes for the lead characters. Fashion magazines and standard patterns are also studied and interpreted to conform to puppet requirements. Designing costumes for puppets presents special problems. A garment may be made to scale size, but the material will often refuse to fold, flow or hang to scale size.

Substitute materials of suitable appearance must be found or improvised and a great deal of ingenuity goes into the solution of such problems. Sometimes, normal materials are used to brilliant effect, like the magnificent miniature mink coat I saw hanging, like the other garments in stock, on its own miniature hanger. Footwear is made by stretching material or leather tightly over solid foot shapes. The most interesting things are the puppets themselves, and one of the most fascinating departments is the puppet workshop under the supervision of John Brown.

Strangely, this is one of the few departments that buys part of its product from outside sources. Bodies and hands, molded in flexible PVC, are copied from master models and supplied in quantity to the workshop by an outside company. This ensures consistency of behavior during manipulation and does not divert the puppet makers from their creative work.

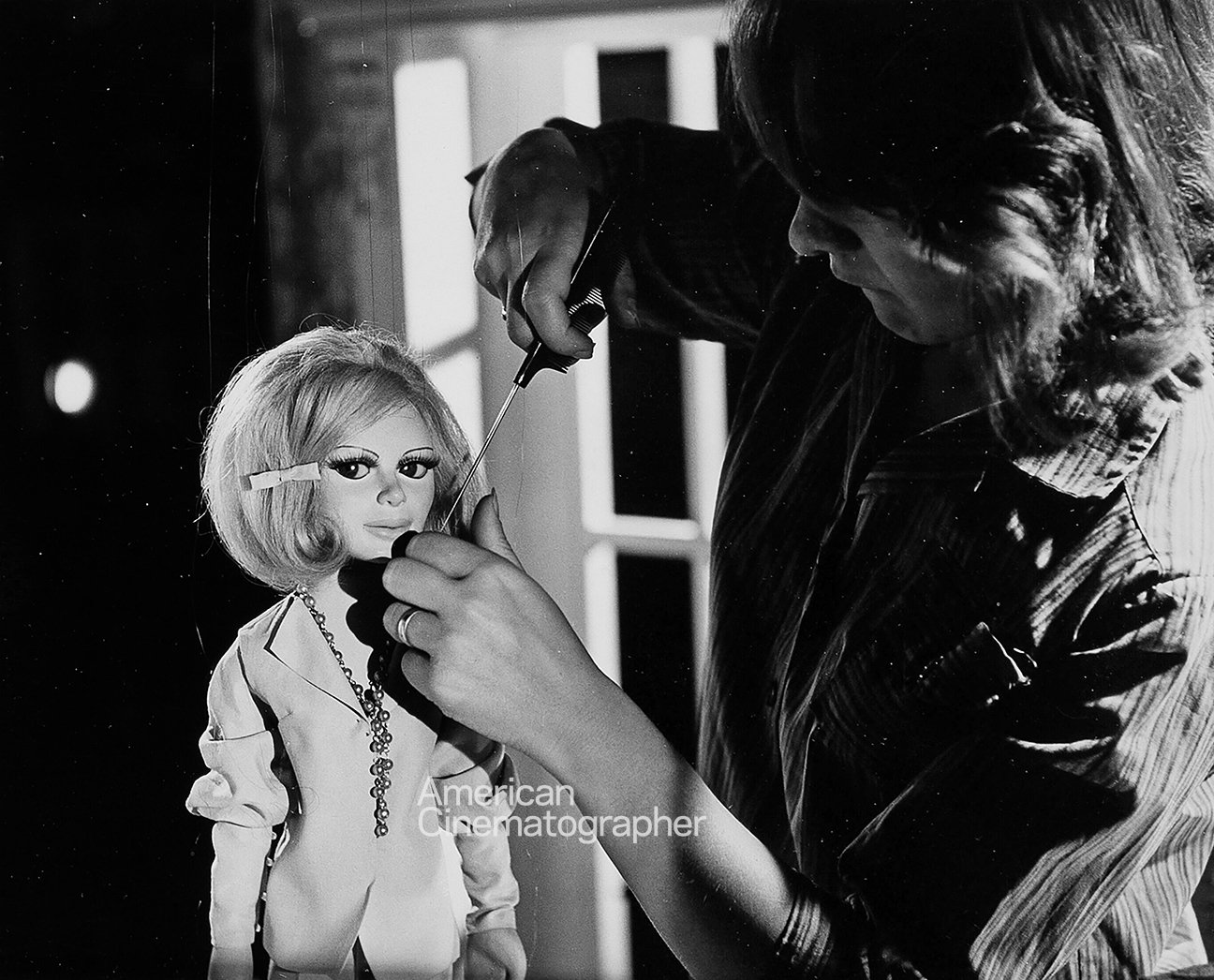

Puppet heads are first modeled in plasticine and each main character is provided with five or six heads; two normal, a smiler, a blinker, a frowner, or other moods according to the requirements of the story. From the plasticine originals, rubber molds are taken and fiberglass casts made from these.

Each head is hollow and is rather large in proportion to the accompanying body, with dark, unblinking eyes, which gives the puppets their characteristic look. The head has to be large enough to contain the electromagnetic mechanism that will enable it to “speak.” The lips and part of the face surrounding the mouth are of soft leather, which is bonded into the main structure. Several coats of paint are then applied and sanded down between each coat, to provide a surface that closely simulates the semi-matte effect of flesh.

The mouth movements of puppets are linked to the dialogue they are supposed to be speaking, by means of the voice recordings that have been made on 16mm coated film. Specially filtered versions of these recordings are played during shooting, under the control of a lipsync operator. The amplitudes of the peaks in the speech cause the AC current supplied to the electro-magnet inside the head to open the mouth. At all other times, it is held closed by a spring.

With this system, the mouth opens entirely and shuts entirely, but a new method has been developed in which DC current of varying power will make the mouths open to different degrees in consonance with the modulations of the dialogue phrases, thus getting much closer to reality. Also, the electromagnetic control system has been moved down into the body of each puppet, so the head and eyes can be of more correct size and proportions. There is also a dual mechanism for moving the eyes.

The “crowd artists” and other subordinate puppets are not made more elaborate than is necessary for their proper functioning, for this is a very expensive part of the operation.

At one time it was perhaps more expensive than it need have been, for it was the custom to break up each puppet when it had served its purpose and a series was complete.

Nowadays, the company is going over to a repertory system for its main artists. Each character will have at least four heads, with 66 characters being planned. Later, another 100 will be made. These will all be photographed and filed in a large volume that will constitute a casting register. From it, suitable characters will be chosen for each new production. The ability to change make-up, hairstyle, beards, clothing, and so on will give a wide range of choices. The repertory system is being adopted in the interests of higher standards of accuracy and quality rather than for economy. It will enable better and more durable puppets to be made.

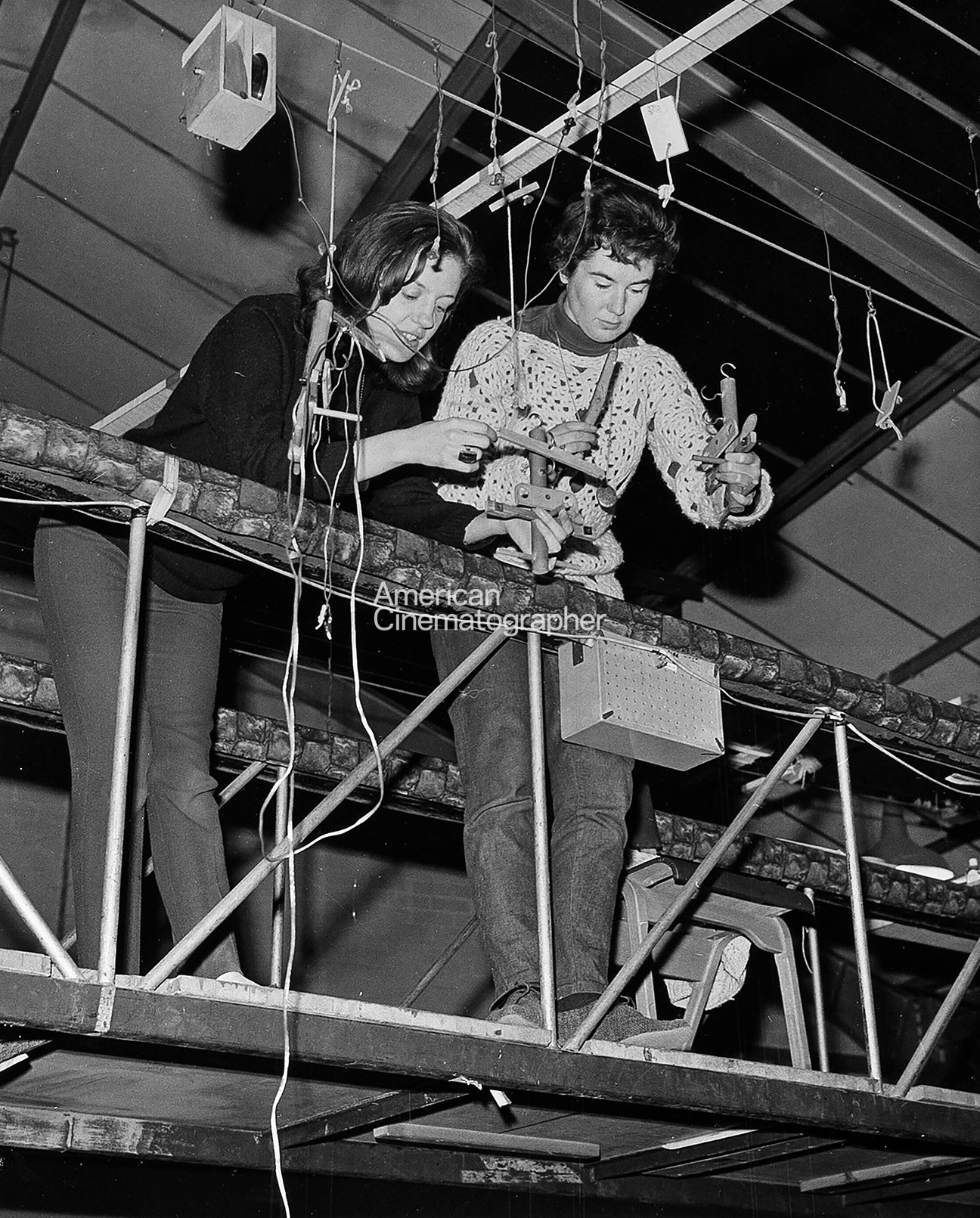

Most of the wigs for the major characters are produced by “Wig Creations,” extensive use being made of mohair. But the hairdressing during production is done by the puppeteers themselves, who also model some of the faces. Puppeteers are, by their very nature, enthusiasts. Not everyone can stand up to the very stringent demands of film puppetry, but two of the puppeteers, Mary Turner and Christine Grenville, have been in from the very beginning.

The puppets are controlled by thin wires from a bridge walkway about 3' wide and 30' long, supported over the stage on a gantry that can be moved easily about the smooth concrete floors of the studios. Above the heads of the puppeteers runs a system of five parallel current-carrying wires, with a guard wire on either side of them. Through these wires will pass the "voice" messages to operate the mouths of the “stars,” in synchronization with the dialogue. The lip-sync operator has a dialogue tape for each “star.” Four playback speakers enable everybody in the studio to hear the dialogue.

A normal puppet unit, besides the camera crew and the lip-sync operator, includes the director, his assistant director, three set artists for dressing the sets, three electricians, as well as two bridge puppeteers manipulating the puppets from the overhead walkway, and a floor puppeteer who checks continuity, adjusts the angle of the puppets to camera, sprays wires “into the scene” so that they are invisible in takes, and sometimes steadies the puppet from off-screen.

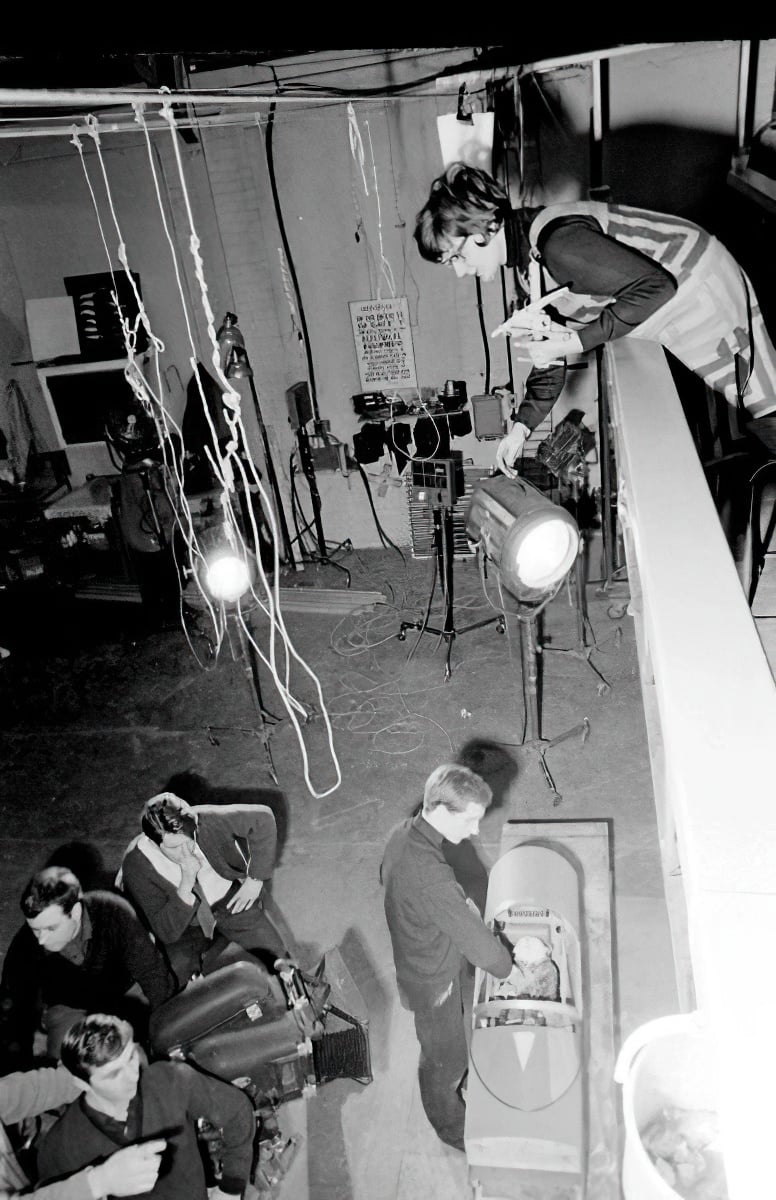

Of necessity, a puppet filming unit must be a tightly integrated team and good communication is essential. After eight years of experiment the answer to this problem has been found in “Addavision,” a system developed by Livingstone Laboratories. Addavision is in effect a small television camera, fitted to a Standard BNC Mitchell, which tells the operator exactly what his camera is seeing and provides an image of such excellent quality and definition that he is able to focus with its aid.

This image is fed to a number of other monitors. Puppeteers usually work by means of reflection in a mirror; so the image on their monitor is reversed for them. Through other monitors around the studio the lighting director, the director, the lip-sync operator in his separate booth, and other workers have immediate access to accurate visual information, without having frequently to interrupt the camera operator in order to look through his viewfinder. Production time is also saved by making videotape recordings of each take. Played back immediately, they avoid unnecessary retakes. Monitors in the offices of the directors of the company and of the producer, enable them to be consulted from the floor and to give immediate opinions or advice based on precise knowledge of what the camera can see. There is also a monitor in the office of the chief electrical engineer so that he can become aware of any technical fault at the earliest possible moment and take immediate steps to deal with it.

Lighting has played an important part in the success of Thunderbirds and John Read, director of photography, is also a director of the company and an associate producer.

In lighting scenes, Read uses puppet “stand-ins” for the stars; cardboard cut-outs for lesser characters. He would rather use a 10K inkie than a smaller lamp any day and is also experimenting with tungsten-halogen lighting. An oscilloscope, driven from the Addavision unit, enables him to keep a constant check on lighting contrasts and to detect unwanted reflections and flare.

Close-up working with puppets, and even more so with the smaller scale models, calls for the use of relatively small working apertures to obtain sufficient depth of field. This necessitates the employment of higher light intensities than are required for full-scale live-action shooting.

The problem reaches its peak in the effects studios, especially when they are shooting in color for the large screen. In order to obtain correct scale movements, effects scenes are often shot at camera speeds of the order of 120 frames per second, and then so much light is needed that sometimes the models start to smoke under it.

Orthodox studio lighting equipment is used. The main problem is to be able to pour enough light onto the sets to overcome the problems of shooting at high speeds, combined with limited depth of field. Colored lights are not used because they would, to an undesirable degree, cut down the light intensity available.

For special effects shots, the S35R Mitchell equipped with all the Bausch & Lomb Super Baltars that will fit it is used. For puppets, with the Addavision system, good use is made of zoom lenses, and in particular the new 24mm-240mm Angenieux. The cinematographers have a couple of pack-shot lenses for big close-ups of puppets. An Arriflex IIB is used, also, for working in rather small sets.

Standard dollies are utilized, some Edwinton, some Pathfinders, with the idea in mind that, with a 3 to 1 ratio, a 3' track on the models is equivalent to 9' in real life. Depth of field is a special problem in moving camera shots.

Little recourse is made to laboratory effects, most special effects being accomplished through manipulation of the models and sets themselves. But there is continuous experiment on mechanical devices and such techniques as back projection and front projection. Again, the biggest problem is the limited depth of field, because of the small size of puppets and sets.

To obtain either a more dramatic or more realistic perspective effect in the recorded picture, sets and properties are sometimes designed with modified perspectives.

Episodes for a television series are completed at the rate of one a week; which means that at least two different ones are on the floor in different studio suites at the same time.

Shooting time for a half-hour episode is two weeks of 5 ½ days for the puppet sequences, under the control of the director, one week of 5 ½ days for the effects sequences, at the rate of about 80 shots a week, under the control of Derek Meddings.

The director has two weeks after shooting during which he works with the editor and supervises final editing. During that same two weeks he is also preparing to shoot the next episode for which he is responsible.

Like all groups of this kind, Century 21 Productions Organization is interested in other enterprises ancillary to its main one. Its two publications, entitled respectively Lady Penelope (after one of its most popular stars) and T.V. 21, are the two largest-selling comic papers in the British Isles at this time.

It has just launched another called Candy, for 4 to 7-year-olds. This paper is not allied in any way to television and four entirely new characters have been created for it — “Candy” a girl, “Andy” a boy, and Mother and Father “Bearanda,” animals with bear bodies and panda heads. Unlike most comic paper characters, these are not drawn, but are life-size models, with movable heads and limbs, who have a real existence in a series of permanent studio sets that represent the kitchen and various living rooms in their house, a shop in the village and, most ingenious of all, in the house, they move up and down between the floors in a lift-in-a-tree. The series of situations in a story sequence are carefully set up and photographed with a reflex camera of the Hasselblad type, to provide color transparencies from which the illustrations for the paper are prepared.

This is but one of a number of exciting and forward-looking developments being engaged in by this enterprising and rapidly growing organization.

The general visual style and production approach of Thunderbirds was later recreated for the 2004 action-film parody Team America: World Police.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.