Taking Flight with Top Gun: Maverick

Claudio Miranda, ASC and director Joseph Kosinski employ the latest gear and techniques to capture genuine high-flying action.

Images courtesy of Paramount Pictures, Skydance and Jerry Bruckheimer Films.

When Top Gun was released in 1986, audiences hadn’t seen anything like it before. Producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer wanted to make a slick, high-octane motion picture about an elite Navy fighter pilot school and fill it with young, good-looking actors and exhilarating aerial photography — and they wanted to do it with real fighter jets. With Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC’s strong, naturalistic cinematography helping to realize director Tony Scott’s stylish vision (AC May ’86) — along with the United States Navy’s cooperation and the onscreen charisma of the film’s star, Tom Cruise, as ace pilot Lt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell — the filmmakers were able to do just that. The movie was a box-office smash.

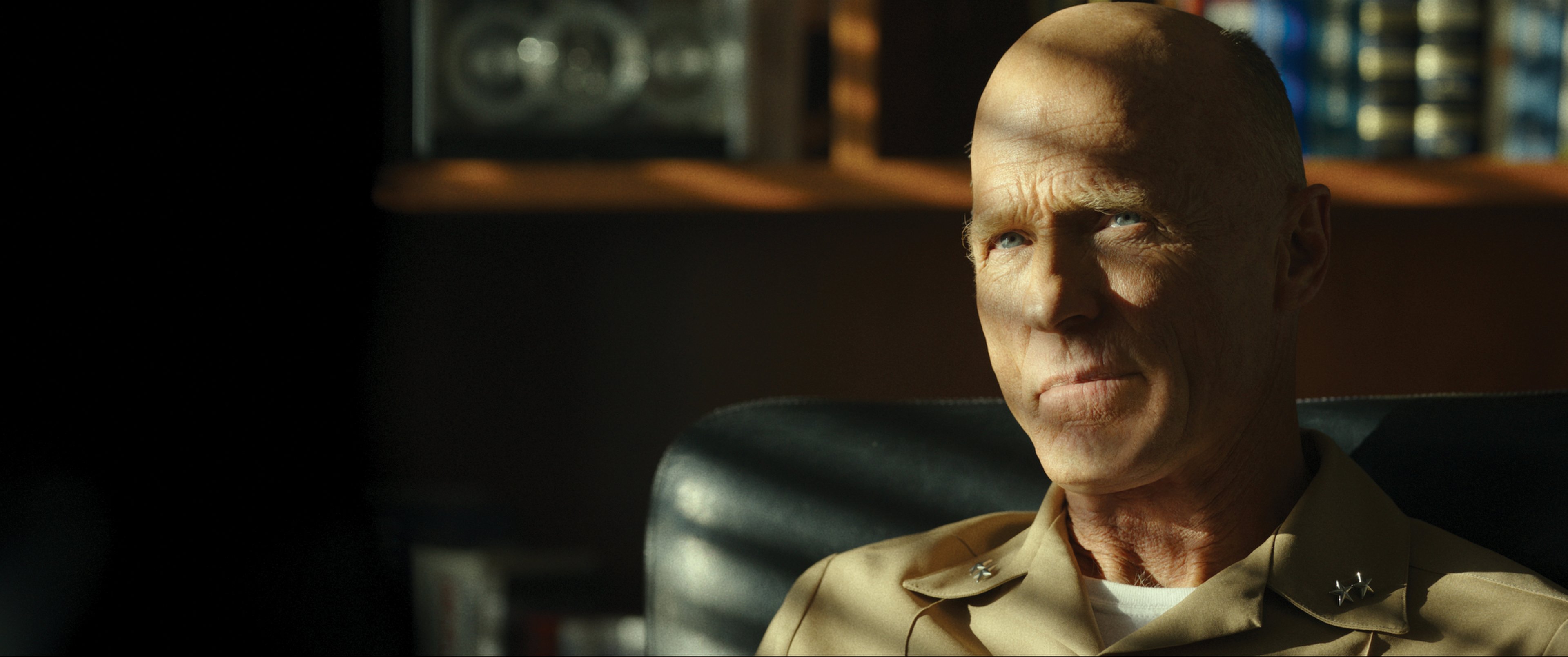

Thirty-six years later, Cruise’s rebellious aviator is back to mentor the next generation of young, good-looking “Top Gun” pilots. To help bring the much-anticipated sequel to the screen, cinematographer Claudio Miranda, ASC and director Joseph Kosinski have harnessed the latest advances in digital-camera technology, optics and support to raise the flight-photography bar for Top Gun: Maverick.

Maverick is the fourth of five feature collaborations between Miranda and Kosinski. The pair, who also partnered on Only the Brave and Spiderhead — and who first worked with Cruise on Oblivion (AC May ’13) — began their professional relationship more than a decade ago with a different kind of sequel. “With Tron: Legacy [AC Jan. ’11], we paid homage to the language of the first film [the 1982 sci-fi feature Tron], but didn’t follow it too closely because it was a different world,” Kosinski says. For Maverick, however, significant cues were taken from the original. In addition to presenting a modern take on the adventures of the elite squadron, “we wanted to take the audience back [to the feeling of the original], too. We wanted it to feel like a Top Gun movie.”

“[The goal was] developing the world’s most impactful aerial cinematography to date.”

Miranda briefly consulted with Kimball regarding the first film’s photography and honored its visual style through the use of graduated filtration. Along with the addition of digital film grain during the final grade (performed by Company 3 senior colorist and ASC associate member Stefan Sonnenfeld), the technique resulted in deep shadows and a dusky look, similar to the original film’s imagery “but with our own flavor,” Miranda remarks. “There’s definitely a warm look to it, more so than the other movies Joe and I have done together.”

Says Kosinski, “Every time we approach a new project, we go into it with the intent of trying something new and shaking things up for us in terms of its technical aspects and visual style. For Maverick, it was about capturing the experience of actually being in one of these fighter jets while it’s in the air. That’s how we were able to go beyond the first film.”

“The secret to making dynamic aerials is to use a variety of platforms to tell the story.”

The thrilling aerial sequences in Top Gun: Maverick are comprised of three main elements: ground-to-air, onboard and air-to-air. The United States Naval Air Systems Command, aka NAVAIR, provided the filmmakers with two Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornet fighter jets to modify for photography, and a decommissioned Grumman F-14 Tomcat for on-the-ground scenes. (Because they are no longer flown by the U.S., aerial sequences involving the Tomcat required visual-effects work to digitally re-skin F/A-18s in flight with the first film’s iconic jet design.)

The actors portraying the Top Gun pilots went through a training program led by the film’s aerial coordinator, Kevin LaRosa Jr., and his father, stunt pilot veteran Kevin LaRosa Sr. During this prep period, the actors worked in a number of different types of aircraft. “We started training them to fly in Cessna 172 Skyhawks,” Kevin LaRosa Jr. says, “then in the highly maneuverable and fully aerobatic Extra EA-300 aerobatic monoplanes to increase their G-tolerance, and then in the Aero L-39 Albatros so they could become accustomed to flying high-performance jets.”

Aerial coordinator LaRosa joined the production a few months before principal photography, along with aerial cinematographers David B. Nowell, ASC (podcast interview here) and Michael FitzMaurice. In developing their approach to filming the aerial sequences, LaRosa and his team assembled makeshift animatics — using iPhones, which recorded stick-model airplanes.

“We built an aerial menu book of the most exciting and exhilarating camera angles and maneuvers that we could think of,” LaRosa says. “Then, we’d go and test them with real aircraft. We’d learn what worked and what didn’t. With the goal of developing the world’s most impactful aerial cinematography to date, the aerial team worked very closely with Joe, Claudio and Tom throughout all the aerial sequences, shot throughout Washington state, Nevada and California.

One of the filmmakers’ key objectives was to capture the effects of aircraft combat maneuvers on the actors’ faces, and the best way to do that was to put the actors into the aircraft with as many cameras as possible. “You can’t get it on a greenscreen stage,” says Miranda.

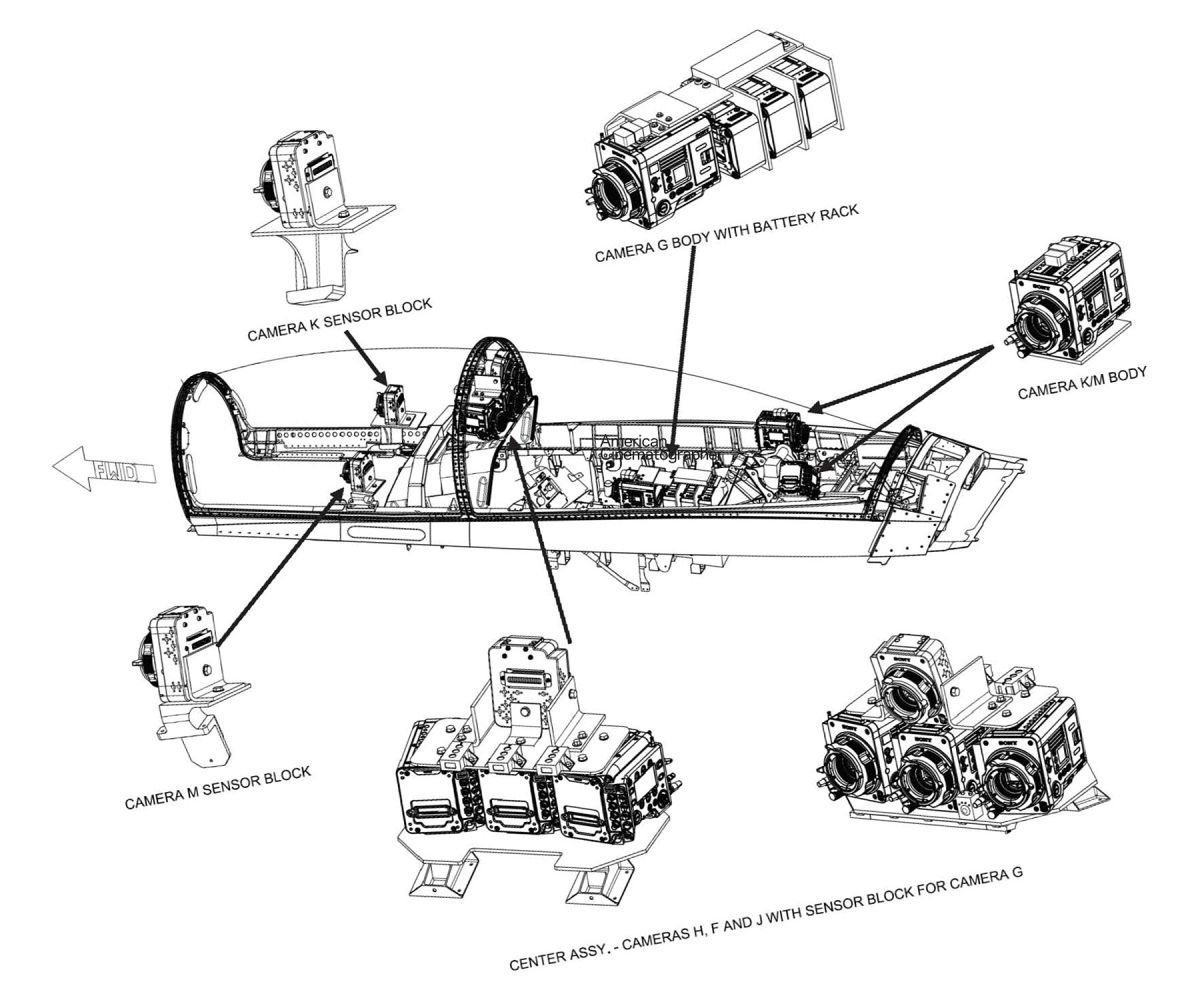

With input from 1st AC Dan Ming and key grip Trevor Fulks, Miranda proposed a six-camera setup for the F/A-18F: three standard Sony Venice units, along with one outfitted with the Rialto system — which allows the camera’s sensor block and lens to be separated from the body, with connection maintained via an extension cable — pointed back at the weapons-systems officer’s seat, and two Rialtos looking forward over the pilot’s left and right shoulder.

“Initially, the engineers at NAVAIR told me [that placing] six cameras wasn’t possible, but we found two F/A-18s without modern heads-up displays,” Miranda says. Once the plans were approved, the jets’ cockpit video-recorder systems and additional hardware were removed. “Trevor designed and machined plates that mounted to the cockpit’s existing threaded holes, and we could rig our equipment off of those,” says Ming.

Light, compact Voigtländer Heliar wide-angle 10mm, 12mm and 15mm E-mount primes, and Zeiss Loxia 21mm, 25mm, 35mm and 50mm E-mount primes were used to give the cockpit cameras as slim a profile as possible. “The path of the ejection seat had to be completely clear, so the lenses couldn’t extend past the glare shield,” says Miranda. “It helped that the Venice cameras have an internal optical ND filter system, so no matte boxes were needed.”

“In the jet cockpits, we needed small and lightweight lenses with close focus.”

The rear-facing Venice cameras were mounted over the glare shield above the instrument console. The body for the rear-facing Rialto system was mounted on top of the aircraft’s light-control box in the rear. To ensure the rigs’ viability, NAVAIR subjected them to shock, vibration and wind-tunnel testing at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland.

The sensor blocks of the forward-facing Rialtos were mounted to the inside of the canopy, while the camera bodies were mounted behind the rear seat. Ming points out that Rialto prototypes were used for these forward-facing units. “In case of an emergency, the prototype cables would easily rip right out of the sensor block. Production Rialtos have much sturdier connections.”

Before each run, Miranda conferred with the F/A-18 pilots about how to get the best light for the cockpit cameras, as the aircraft roared through valleys and around mountains. “I wanted the sun to come three-quarters from the rear on either side. The main idea is to be backlit,” the cinematographer says. “After all that planning, we still had to guess the exposure. Then once we set the stop on the cameras, that was it.”

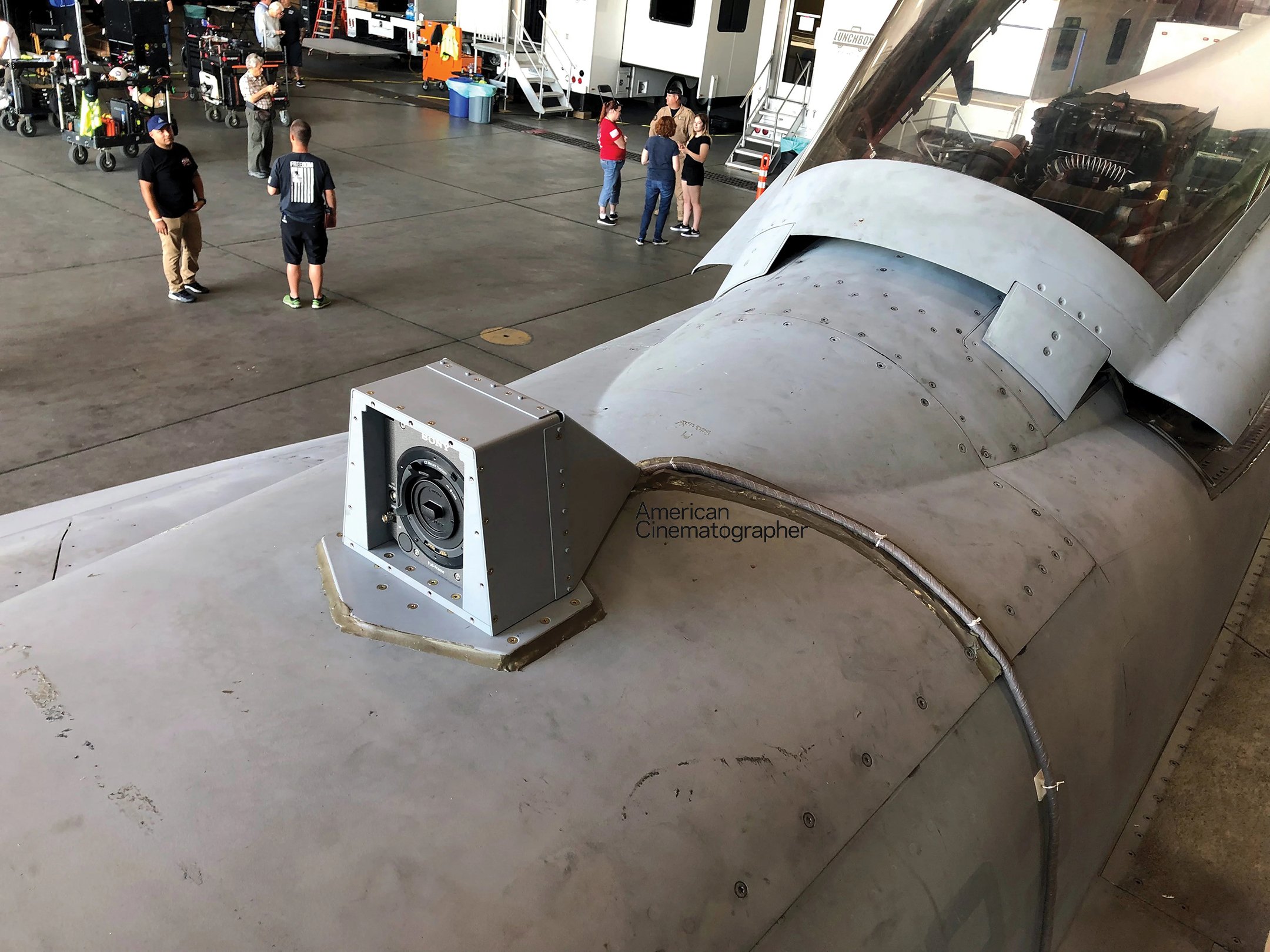

NAVAIR built custom housings for cameras mounted to the exterior of the F/A-18. Venice bodies equipped with Heliar wide-angle primes could be mounted front- and rear-facing to the centerline of the jets’ bellies, and to the underside of the wing facing toward the fuselage. A rear-facing Rialto was mounted to the top, behind the cockpit, with the camera body secured in a compartment beneath the aircraft’s paneling. Up to four cameras could be mounted to the exterior at a time.

The position of an externally mounted camera sometimes influenced what kinds of maneuvers could be performed. “Certain mount areas were subject to extreme vibration during certain maneuvers, as we learned when a camera came back damaged in the housing after a run,” Ming says. “We also got internal ND movement with the extreme vibration that Sony said they couldn’t replicate, so I suggested they test it with a paint mixer to match what we were experiencing.”

Says Miranda, “If the jet senses there’s a load on the wing, it will limit its own flight characteristics — [it] can’t pull 7½ Gs, and it won’t roll. [But] if the cameras are on the aircraft body or inside the cockpit, you get full performance.”

The production had two interior-rigged jets and one exterior-rigged jet. “Since the exterior rigs limited the performance of the planes, they were never on the same jet as the interior rigs,” Ming says.

In addition to his duties as aerial coordinator, LaRosa also served as the film’s lead camera pilot. Three different approaches were taken to capture the high-speed maneuvers of some of the world’s fastest fighting machines.

The first system was the CineJet, a modified Aero L-39 Albatros trainer jet with a six-axis gyrostabilized Shotover F1 camera platform mounted forward of the nose. The Shotover system’s maneuverability, combined with the mounting position and flat belly of the L-39, offered the operator — either Nowell or FitzMaurice — a wide field of view, including below and behind. The CineJet was employed for high-action aerial dogfights and low-altitude precision maneuvering.

Halfway through production, an Embraer Phenom 300camera jet was integrated for missions requiring additional time in the air, which included extended operations over water. The Phenom light private jet is a bigger aircraft than the L-39, but faster and capable of longer flight times. It was outfitted with two Shotover F1 Rush platforms — one on the nose and one under the tail. Nowell and FitzMaurice could comfortably fly in the jet simultaneously, each operating one of two Venice cameras, paired with either a Fujifilm/Fujinon Cabrio 20-120mm T3.5 or a Cabrio 85-300mm T2.9-4 zoom.

LaRosa also flew an Airbus H125 single-engine helicopter, whose primary role was to provide an aerial camera that didn’t move at the speed of an airplane, and could therefore, at select moments, help to enhance the audience’s sense of the fighter jets’ terrific speed and agility. The helicopter was mounted with a Shotover K1, a bigger version of the F1 designed to fly larger camera configurations or longer lenses — which, in this case, included the larger profile of Fujinon’s Cabrio 25-300mm T3.5. One example of an H125 shot was LaRosa hovering low to the ground, but still close to action altitude, as a fighter jet ripped across the terrain at more than 300 knots.

“With a combination of angles from all of these different camera platforms, we’re able to really give the audience a thrill ride and create powerful aerial sequences,” LaRosa says.

Miranda adds, “The aerial work is pretty spectacular. There’s a lot of effort up there on the screen.”

You’ll find our complete episode of the AC Podcast with aerial cinematographer David B. Nowell, ASC here.

Like cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC on the original Top Gun, fellow Society member Claudio Miranda chose to shoot Maverick entirely with spherical lenses. Says Miranda, “In the jet cockpits, when you’re pulling five to seven Gs, 10 pounds becomes 50 to 70 pounds, so we needed small and lightweight lenses with close focus.”

The cinematographer’s main-unit prime-lens package comprised Sigma High-Speed Cine primes in the 14mm-40mm range, and Arri/Zeiss Master Primes from 50mm upwards. Miranda generally shot in 6K full frame — with exceptions including sequences captured with lenses that didn’t cover the full Venice sensor — and framed for 2.39:1 and Imax 1.9:1. The main unit also carried a set of three Fujifilm/Fujinon Premier Zooms, from 18mm-400mm, and the company’s Premista 28-100mm T2.9 zoom, as well as a set of three Zeiss Compact Zooms, from 15mm to 200mm.

The ground-to-air unit employed two Premier zooms, from 24mm-400mm, and two rehoused Canon lenses — a 150-600mm still zoom and a 1,000mm telephoto lens, both capable of covering 6K full-frame. Even at extended focal lengths, the operators used IBE Optics PLx2 extenders to track far-off aircraft through the sky, which sometimes called for the use of modified riflescopes atop the cameras to aid them in sighting their targets.

2.39:1, 1.90:1 (for Imax presentation)

Cameras: Sony Venice

Lenses: Main Unit | Sigma Prime; Arri/Zeiss Master Prime; Zeiss Compact Zoom; Fujifilm/Fujinon Premier Zoom, Premista Zoom; Cinemagic Revolution snorkel-lens system || Jet Interior and Exterior | Voigtländer Heliar Hyper Wide, Ultra Wide, Super Wide; Zeiss Loxia || Air-to-Air | Fujifilm/Fujinon Cabrio zoom || Ground-to-Air | Fujifilm/Fujinon Premier Zoom; Canon zoom, prime