Art Leads the Way: Filming Once Within A Time

Cinematographer Trish Govoni re-teams with director Godfrey Reggio for a modern bardic tale.

Production photos courtesy opticnerve™.

As a filmmaker, Godfrey Reggio’s best-known work is inarguably The Qatsi Trilogy: Koyaanisqatsi (1983), Powaqqatsi (1988), and Naqoyqatsi (2002). Each entry in this sprawling, experimental series examines the tense, inextricable relationship between the natural world, humans, and the technological world of humans, using existing and original documentary footage (photographed by Ron Fricke, Leonidas Zourdoumis and Graham Berry, and Russell Lee Fine, respectively) backed by the soaring orchestrations of Reggio’s longtime collaborator Philip Glass.

In 2023, Reggio and co-director Jon Kane turn their attention to a new generation of humans for Once Within A Time, shot by cinematographer Trish Govoni, who had previously collaborated with Reggio and Kane on 2013’s Visitors. “I don’t like to make comparisons, but we essentially created a ‘Kiddie-qatsi,’” Reggio quips on a call from his home in New Mexico. “This film is addressed to children, who are on the ‘net all day long, being exposed to all of these negative influences, yet are highly adept with technology, surpassing even their parents in knowledge. They experience more images in a day than children in the Middle Ages did in a lifetime.”

“Working with Godfrey is a unique experience... We don’t follow conventional methods like creating storyboards or shot lists. It’s about diving in, shooting tests, and evolving.”

— Trish Govoni

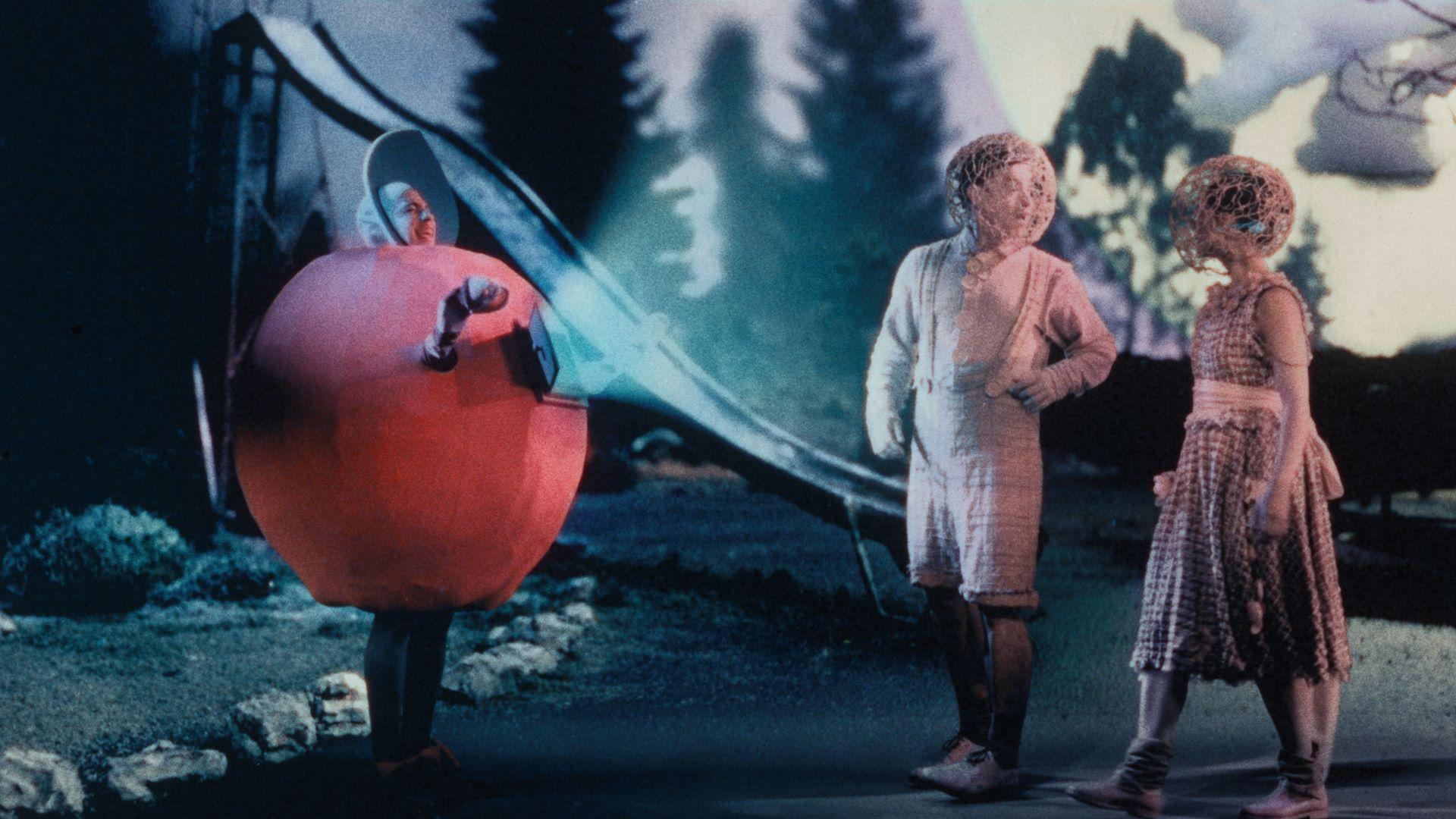

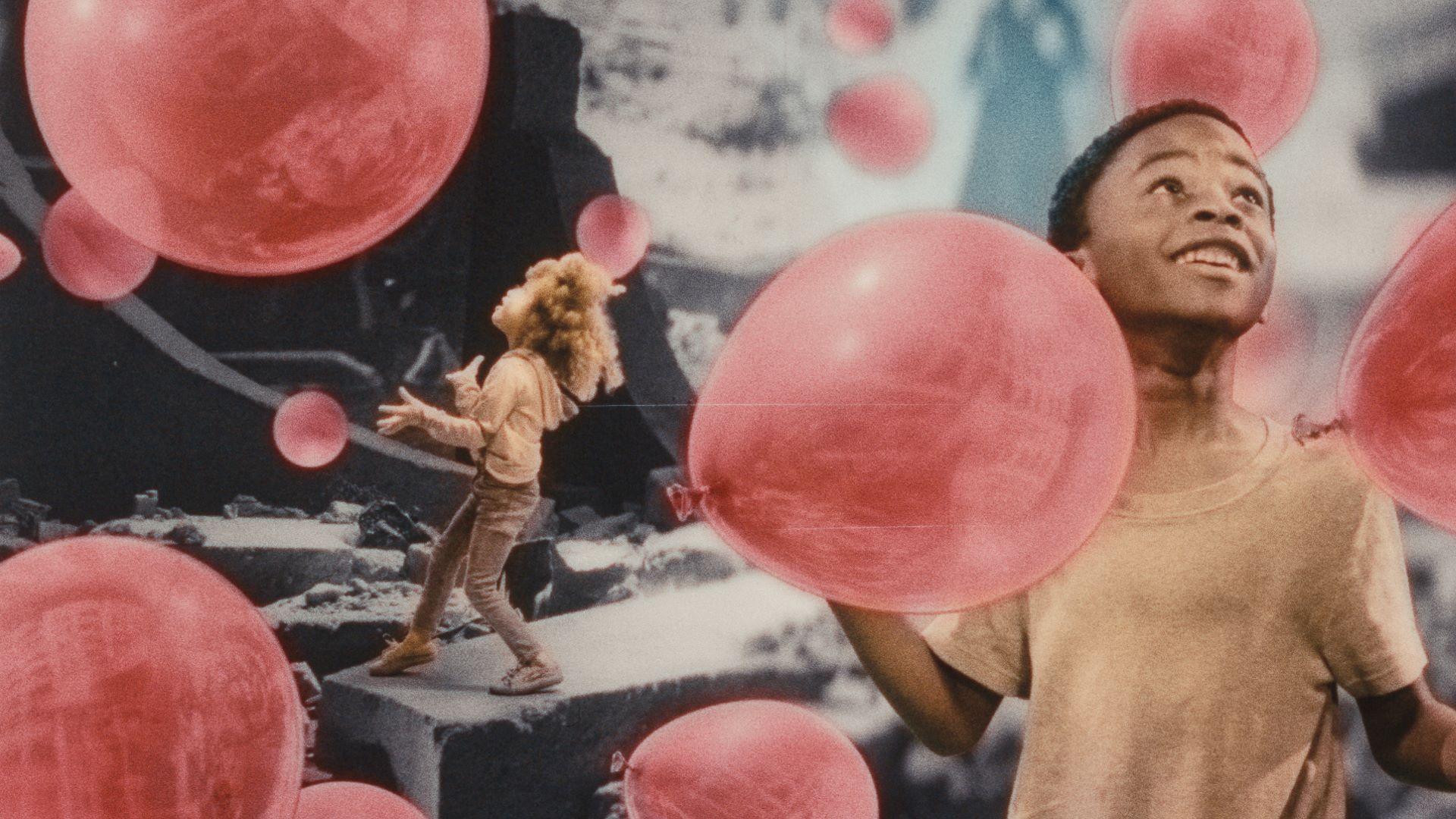

Like many of Reggio’s previous films, Once Within A Time is dialogue-free, relying heavily on montage and Glass’s urgent compositions for maximum impact. Unlike his other work, it employs a definite story, unfolding in a three-act structure that revolves around a pair of innocent twins (Apollo Garcia Orellana and Tara Khozein) who are cast out of their idyllic playground and made to confront an overwhelming modern world.

“We’re telling a bardic tale, reminiscent of the era of Homer and the pre-Socratic philosophers, who relied on oral storytelling,” Reggio explains. “In a fairy tale, there’s always a happy ending. We end with a question about our age: is it the sunset or the dawn?”

“From the start, the film’s central theme has been ‘children resisting a destiny of annihilation,’ and Godfrey wanted this film to conclude with a sense of hope,” Kane elaborates on the same call. “So we aimed for a hopeful ending, but one without definite answers.”

Also unlike any of Reggio’s previous films, the images of Once Within A Time were created — sculpted, one might say — with visual effects, though most of the elements originated as 1/25-scale practical miniatures and full-scale live action, photographed by Govoni at opticnerve™ in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

Reggio carefully chooses his collaborators based on their ability to communicate, in addition to their work. “I like to see them in person and read their face as they talk to me, because they could be a genius, but not able to collaborate and take criticism,” he says.

He was as impressed by Govoni’s creative talent and technical proficiency as he was her professional demeanor and openness to interpreting his ideas. Govoni admits to being “a little bit intimidated” on her first meeting with Reggio.

“He’s seven feet tall. He speaks in metaphors. I think he’s truly the smartest person I’ve ever met,” she relates in an interview with AC. “But you find a rhythm with people.” On Visitors, she worked primarily with Kane; on Once Within A Time, she and Reggio collaborated more directly.

“Working with Godfrey is a unique experience,” Govoni continues. “He does his research and uses visual references, but we don’t follow conventional methods like creating storyboards or shot lists. It’s about diving in, shooting tests, and evolving.”

The underlying process of Reggio’s scenario involves a meticulously crafting of ideas the form of written notes, ciphers, and drawings, then distributing them to key crew members to interpret as they saw fit, using their shared understanding of his singular vision to guide them.

The filmmakers wanted Once Within A Time to feel timeless and handmade, like a scratchy, hand-cranked, hand-tinted film of the past, but one concerned with contemporary matters like social media and climate change. Govoni’s camera captures each scenario as she would a theatrical production (or the workshop of Georges Méliès). In fact, the film opens and closes with a curtain, and its whimsical miniature sets — the playground, an industrial tower of Babel, a mirrored digital landscape, to name a few — belie the Broadway pedigrees of set designer Scott Pask and art director Frank McCullough.

The project took eight years from concept to completion. In that time, it morphed from a 3D IMAX presentation to a stage opera before taking its final form. Photography lasted sixteen months, starting at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It was like going to camera camp... Each day was unpredictable. It was a very creative space.”

“They’d been prepping and testing for months before I joined full-time,” Govoni recalls. “The miniature sets were mostly designed and constructed. My initial reaction to the live-action greenscreen was that it was too small — twenty feet wide in a room with ceilings just barely over nine feet. I suggested moving to a different studio for more space, but the decision was to stay, because it meant we got more shooting days. This confinement shaped our lighting methods and lens selection.”

Govoni had worked on commercial shoots with miniatures before, “but never on this scale.” The proscenium setup simplified her approach. The set was a half-circle platform, approximately 6' wide by 4' deep, with a 14' wide by 5' tall projection screen wrapping around the background. “We primarily stuck to the edges of this proscenium, rarely moving in to what we called ‘center stage’ where the turntable was. We noted precise measurements for the 25/1 ratio between the miniature camera and the full-size greenscreen elements. This attention to detail was crucial for the shots that led in and out of the scenes.”

Creating depth within the miniature spaces posed a significant challenge, especially with the wraparound projection screen limiting Govoni’s lighting options. She used Lume Cubes — small LED box lights typically used for DSLRs and underwater photography — in a variety of configurations, as well as model train lights and RGBW LED strips. “It was crucial to light the detailed backgrounds without flattening them,” she says.

High-quality optics were used for achieving the desired depth of field and image sharpness. Miniatures were photographed with a Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 4K, which features a Micro Four Thirds lens mount and smaller-than-35mm Four Thirds imager, “as the depth of field matched well with the larger-scale greenscreen work,” says Govoni. “We used Voigtländer Nokton 10.5mm and 17.5mm lenses, which significantly improved image quality compared to the test footage.”

Govoni shot most of the miniature plates at f/2.8. Stand-in dolls were placed where live-action actors would appear, and she set her focus to them, letting the background elements fall off.

In between miniature setups, Govoni, Kane and Reggio tested various elements, like flickering fire and rippling oil. “It was like going to camera camp,’” says Govoni. “Despite the lack of exactitude, this approach never felt wrong. Each day was unpredictable. It was a very creative space.”

Govoni’s live-action crew was minimal: 1st AC Vanina Feldsztein, gaffer Frankie Florencio, Best Boy electric Francisco Amaya, DIT/CGI artist Raunak Kapoor, and anyone else on set who could spare a hand. “Again, this limitation actually shaped the project,” she reasons. “A larger studio and more equipment wouldn’t have given the film its distinctive feel. The smaller scale allowed us more time with the kids, the miniatures, and to rethink or recreate as needed. It’s not just about technology in art making; it’s about the team coming together to find creative solutions.”

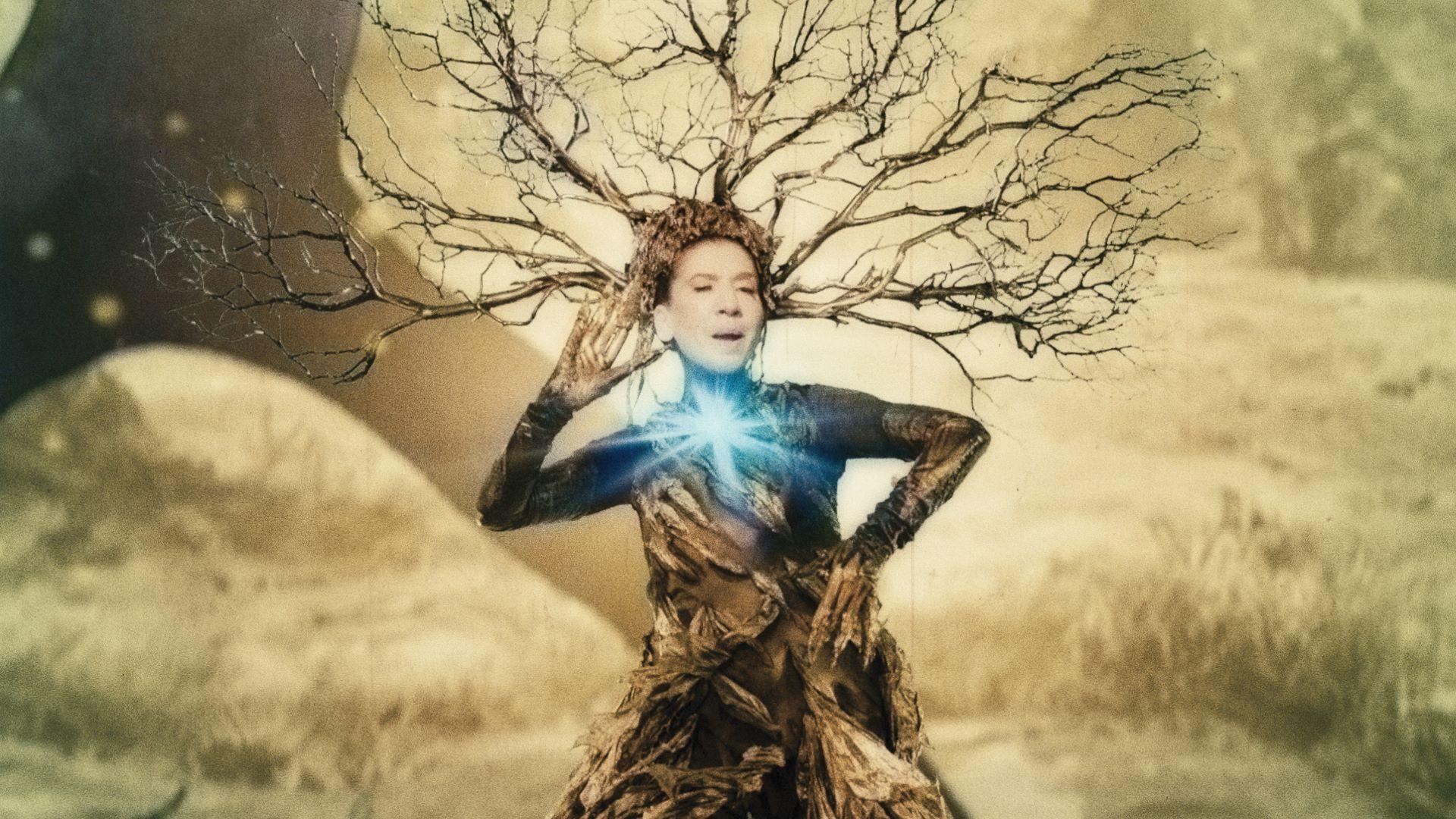

For these elements — including the innocent twins, the Apple Salesman (Brian Bellot), the dryad Mother Muse (Sussan Deyhim), and a shaman played by none other than Mike Tyson — Govoni used her own Arri Amira. Much of the filming was done with a Fujinon Cabrio 19-90 T/2.9 zoom lens. Mother Muse’s closeups sometimes required the tighter framing of a Canon 30-300 T/2.95-T/3.7 zoom.

“The day with Mother Muse was our largest production day; and we used a dolly,” says Govoni. “The rest of the film was shot locked off. It just doesn’t look that way when you're watching it because Jon cut it so well.”

Live-action elements were filmed wide open on both zooms. “The scale of 1/25 and the Micro Four Thirds sensor, which is smaller than the Amira sensor, matched reasonably well,” Govoni reflects. “It wasn’t exact, but adequate for an art film.”

“Art adopts the technology of its time.”

— Godfrey Reggio

Much of the Amira footage was captured at 24 frames per second in 3.8k UHD, but Govoni also often shot at 200 frames in 2k resolution.

“One aspect I appreciate about working with Jon and Godfrey is their indifference to the industry’s obsession with high resolution,” she comments. “This approach is refreshing in a time where filmmakers are preoccupied with shooting in 8k or 6k. It wasn’t that we were indifferent to shooting the highest resolutions possible — especially because the images were going to be manipulated in post — but a higher resolution doesn’t necessarily enhance the story.”

All of the footage was heavily altered and composited by visual effects creative director Grier Dill and his team of artists to look like a hand-tinted silent film from the 1920s. Later, Govoni worked closely with Reggio and colorist Nat Jencks to bring the locked cut into balance. At the end of the film’s credits, the text “Handmade at opticnerve™” appears.

“Our challenge was to achieve this aesthetic without it appearing gimmicky or like a mere digital filter,” says Kane. “Every object and effect was physically constructed and manipulated. There are no 3D-generated characters; everything is based on real objects and people we filmed. We digitally hand-rotoscoped each frame. It’s as handmade as computers get.”

“Art adopts the technology of its time,” Reggio muses.

Govoni appreciates this approach, and the fluid, freeform manner in which it was all accomplished. “The most rewarding part of my work with Godfrey and Jon is getting to be part of an art-making process that isn’t driven entirely by commerce. The freedom from that constraint is a gift to any filmmaker.”