Twelve Monkeys: A Dystopian Trip Through Time

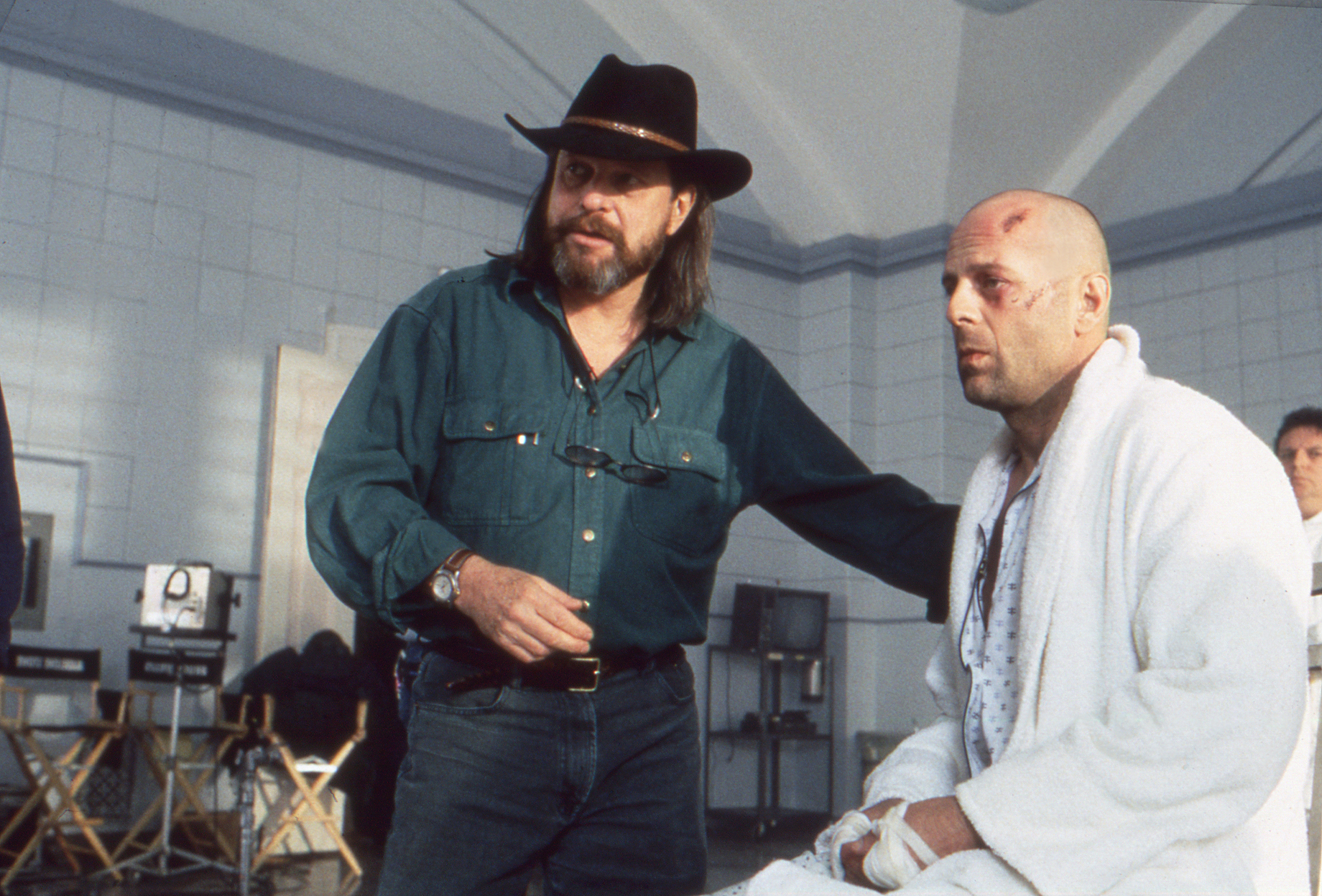

Cinematographer Roger Pratt, BSC helps director Terry Gilliam create a visionary mix of science-fiction, adventure and romance.

Cinematographer Roger Pratt, BSC's association with director Terry Gilliam began, appropriately enough, during a hunt for the Holy Grail.

In Pratt's case, the grail in question was a 14mm lens, which had been left behind when the infamous Monty Python comedy troupe trekked off to a mountainside location to film the hilarious Bridge of Death sequence for their 1975 feature Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), a rollicking, low-budget lampooning of the King Arthur legend.

Destined to be a cult classic, Holy Grail was co-directed by Python's eccentric pair of Terrys, Messrs. Jones and Gilliam. The latter's fiendishly surreal cartoon creations had added an extra dollop of dementia to the troupe's loony, much-beloved television series (earning him a British Academy Award for graphics in 1969), and Gilliam had also contributed his acting, writing and animating skills to the Python group's 1972 film debut, And Now for Something Completely Different.

Before crossing the Bridge of Death, however, Gilliam would need a helping hand from Pratt, then an enterprising clapper/loader. Apprised of the missing wide-angle lens, Pratt took it upon himself to defy the daunting terrain and ensure its retrieval; the journey would prove to be a momentous turning point in Pratt's nascent career. Recalls Gilliam, "We were filming the Bridge sequence up on a mountain, at a place called Glen Cove. We were about a mile and a half from the road; to get to it, you had to descend down the mountainside, cross a river and go up the other side. When he found out that the lens was missing, Roger disappeared and was back with it in something like 10 minutes! I thought to myself, 'This is an extraordinary character.' We've been buddies ever since."

"Terry thought that I had somehow magicked up the lens," Pratt offers with a chuckle. "He considered it a kind of supernatural event."

In fact, Pratt's feat could be construed as the film industry equivalent of alchemy, spurring his transformation from an eager assistant into a highly respected director of photography. The first reward for his misty mountain hop was a Grail cameo in which he is identified as the film's beleaguered Clapper Boy; years later, his friendship with Gilliam would lead to enviable gigs as cinematographer on the director's most successful pictures, Brazil (1985) and The Fisher King (1991), and as director of second-unit photography on the fantasy epic The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989). Pratt's resume also includes collaborations with Tim Burton (Batman), Neil Jordan (Mona Lisa), Kenneth Branagh (Mary Shelley's Frankenstein) and Richard Attenborough (Shadowlands).

From Midlands to Movies

For Pratt, such assignments are the culmination of a longtime love of the cinema. Raised in Leicester, in the English Midlands, his interest in movies was sparked by his father, a priest who frequently showed religious films at his parish. To the youthful Pratt, however, a career in motion pictures seemed remote at best. "Seeing those images on the screen gave me a complete thrill, and I began thinking seriously about pursuing movies as a vocation," he says. "But being in the middle of England, nobody knew what to suggest as a course of action. It was only when I'd been to college that I decided to go to the London Film School. The people there were divided into two basic types: most people wanted to be directors, and the rest of us shot their films for them. Very early on I decided I didn't want to direct; I wanted to be involved in the camera side of it. But I still did a number of assignments with sound and editing just to get the experience."

AC Jan. 1996. Some images may be

additional or alternate.

After graduating, Pratt found that he needed to gain entry into the union, so he obtained a job at a film laboratory, where he spent several years resurrecting black-and-white movies and old nitrate films for foreign television. He then began working as an assistant on documentaries and any other productions he could find. "That's when I got involved with an outfit called Chippenham Films, which had connections with the Monty Python crowd," he relates. "Python used to produce and shoot short films that Chippenham sold to business conventions that needed a bit of comic relief. Eventually, after many years, I was asked to be the loader on Holy Grail, and that's when I met Terry."

The cinematographer notes that the Python troupe encouraged all hands to pitch in with ideas, an ethic that is still evident on Gilliam's sets today. Pratt soon applied that experience to his own career path, which began progressing along traditional lines. "I was working on commercials, and I gradually moved up from loader to focus puller to doing a bit of operating," he says. "I was starting to do a bit of my own camerawork on drama documentaries, and it got to the point where I'd done a few commercials. At about that time, Terry was gearing up to do a short sketch film called The Crimson Permanent Assurance, which wound up being part of Monty Python's Meaning of Life. He asked me to photograph that, and said it would be about ten days' work; six weeks later, we were still at it!"

From there, Pratt stayed behind the camera, and wound up shooting a short film called Dollar Bottom for director Roger Christian, who subsequently asked him to serve as director of photography on The Sender (1982), a modestly-budgeted parapsychology thriller. Gilliam was impressed enough to offer Pratt the cinematographer's slot on Brazil, a Kafkaesque black comedy of majestic proportions.

Prior to the film's release, Gilliam endured a pitched battle with Universal Studios over the film's running time and downbeat ending, but the director held his ground and was able to keep his vision intact. Upon its release, Brazil was hailed by critics and remains a favorite of film buffs everywhere. "Brazil was a huge step up for me, and I was very grateful to Terry for giving me the chance," Pratt says. "Terry's one of the most talented directors I know, and his great strength is that he has a total grasp of the entire canvas. He knows about graphics, music, writing, editing, marketing, distribution, you name it. I think all great films are conceived as a whole right from the beginning. When we're working, there is no firm cutoff point between Terry and anybody working on the film. He's a very democratic person, although he is very clear about the general direction of what he wants to see. He begins designing the look of his films at the very start of the project."

Tackling Twelve Monkeys

Gilliam's firm understanding of the movie-making machine's various gears certainly came in handy on the duo's latest ambitious undertaking, Twelve Monkeys. The film's screenplay, by David and Janet Peoples, was inspired by Chris Marker's 1963 French sci-fi featurette La Jetee, which told its unusual story almost entirely in black-and-white still photos. While elements of La Jetee were retained for the new script, Twelve Monkeys has considerably expanded the tale's visual and narrative scope. The new version of the story begins in the year 2035, when 99 percent of the Earth's population has been wiped out by a mysterious plague; the survivors of this holocaust eke out their existence in a desolate underworld. In the hopes that the resources of the past might help them rebuild the future, a group of scientists living beneath the once populous city of Philadelphia decide to use time-travel to send a lone explorer back to 1996, where he may be able to discover the source of the fatal contagion.

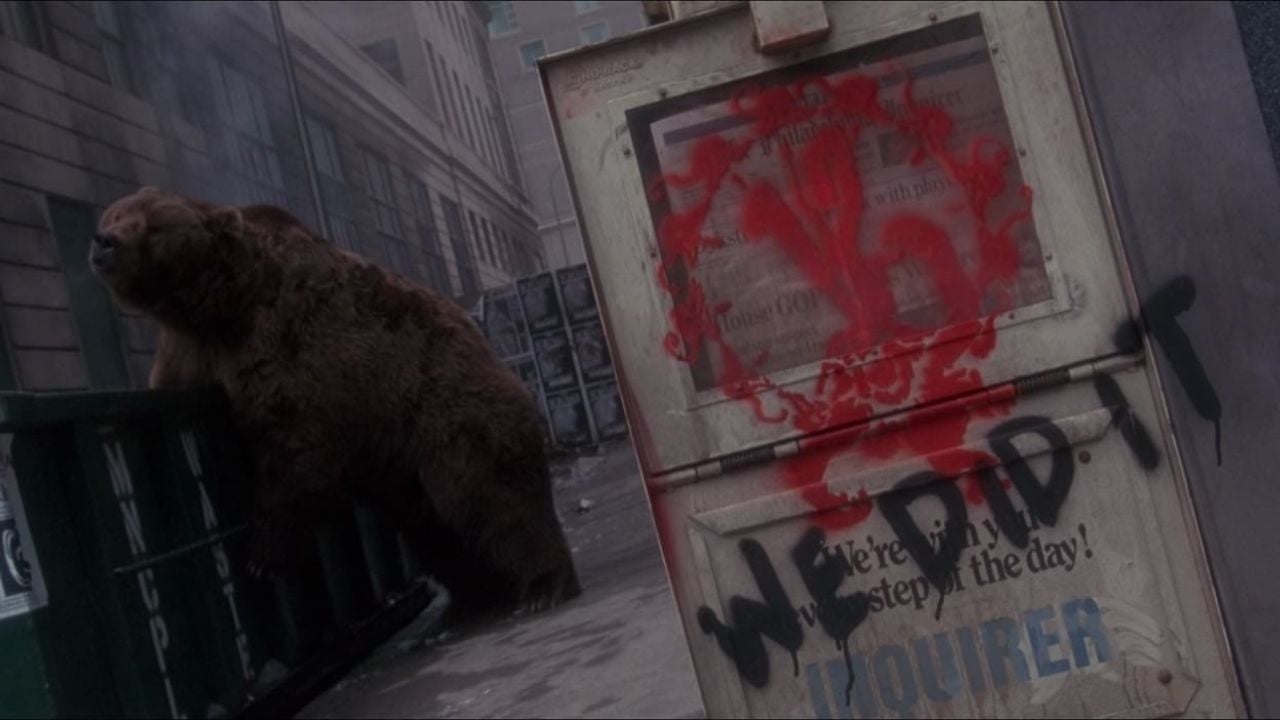

After considering various candidates to carry out their perilous plan, the scientists select Cole (Bruce Willis), a convict who is continually haunted by a mysterious image from his childhood. Upon arriving in 1996, Cole meets Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt), the mentally unstable son of a renowned scientist, and Dr. Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe), a psychiatrist and author who specializes in the study of madness and prophecy. Railly soon diagnoses Cole as a delusional madman, but as their relationship progresses, she begins to believe his dire account of mankind's fate. As the two attempt to unravel the source of the Earth's decimation, they focus on the only two clues they have: Cole's opaque childhood memory and a series of puzzling symbols created by a group known as the Army of the Twelve Monkeys.

In planning the visual design of the film, Gilliam drew upon a variety of reference materials, focusing primarily upon the work of architectural artist Lebbeus Woods. Gilliam describes Woods as "a visionary who does these great drawings of impossible architecture. His work was a big influence on the look of the film's futuristic sequences." Pratt notes that Gilliam's love of architecture, with its vertical lines, is one reason that all of his pictures, including Twelve Monkeys, have been shot in the 1.85:1 format rather than anamorphic.

Bent on creating a uniquely memorable vision of the future, Gilliam enlisted the aid of veteran set decorator Crispian Sallis, whose credits include JFK, Driving Miss Daisy and Aliens. Sallis was charged with creating a future world crammed with "found articles" from the pre-disaster past. The resulting hodgepodge of materials led the designer to explore some eccentric options, such as turning an old sander into a doorknob and a vacuum cleaner into a flashlight. While scouring flea markets and salvage warehouses, Sallis and his crew collected scores of items from a variety of eras, including the Renaissance, the Victorian Age, World War I and II, and the Fifties and Seventies.

During the film's pre-production stage, Gilliam invited Pratt to his home in England several times to discuss his concepts for the picture's look and photographic style. The director then embarked on a series of scouts to find locations that matched his imaginings, accompanied by location manager Scott Elias and production designer Jeffrey Beecroft (a two-time Oscar nominee for his work on Dances with Wolves and Stop Making Sense). After considering New York, Los Angeles and London as primary sites, Gilliam instead opted for Baltimore and Philadelphia. "The film boards in both places were extremely helpful. It was always the plan to shoot on location, because the film was meant to take place in the real world," notes Gilliam. "I actually prefer working on location, because you can find little surprises along the way, things that might inspire you to think differently than you might in a very controlled [studio] setting."

A lover of jazz music, Gilliam says that he often tries to improvise during filming. Of course, such flights of fancy can be a bit risky on the kinds of large-scale projects that the director favors. "As a former animator, I've done my share of storyboards, but I've gotten more and more away from them," Gilliam asserts. "On this picture, I did hardly any at all. It's interesting to see if you can do things instinctively — to go to a location and see what's there on that day. Sometimes, when you preconceive things and think about them for three or four months, you get yourself into a trap. Of course, there are always some complex shots you need to plan out well in advance, but the danger is that you've spent so much time seeing them that you can become bored by the time you're ready to do them. Then again, quite often you may deviate from your plan at the last minute, only to realize, after you've cut it all together, that the original idea was the right choice after all!"

While canvassing the concrete-crammed urban landscapes deep within the two cities, Gilliam and his companions discovered a treasure-trove of bleak, forlorn sites perfectly suited to the story's aura of apocalyptic decay. Chief among these were Philadelphia's disused Richmond and Delaware generating stations, which had once supplied electricity to the entire city, and Baltimore's rotting Westport power plant, on the shores of the Patapsco River. Other Philadelphia sites included Memorial Hall, the last remnant of the 1876 centennial World's Fair Exposition, which was cast as a university lecture hall; the deteriorating Met Theater, which became a homeless enclave where Cole does battle with a pair of vicious vagrants; the Greek-revival Ridgeway Library, a once-majestic structure now awash in graffiti scrawls; the Eastern State Penitentiary, which was turned into a present-day mental institution; and Philadelphia's new convention center, which doubled as the airport featured in Cole's recurring dream. Says Pratt, "The kinds of places we ended up shooting at were disused theaters and ugly sections of town — abandoned places that had faded and fallen into disrepair."

Serving up the film's photographic recipe, Pratt relates, "The overall concept was that the people who were stuck underground were dependent upon a kind of under-powered, shaky generator that gives them tungsten light that's not up to par. There, we used a kind of sepia look with warm pools of light. When Cole goes above ground, he's in a twilight area of snow, a place where there are no human beings, just animals. It's a fairly simple look — cold, darkish, unfriendly daylight. Once we got into the everyday world of 1996, we went after a drab feel because of the places Cole and Dr. Railly encounter on their search for what actually happened to the world."

Pratt felt that Kodak's 5298 stock would be best suited to the task, and he used it exclusively. "I find that the 98 is adaptable to most situations," he says. "What happened to us time and time again, working during the winter, was that we'd start out shooting brightish days and then see it all go to ratshit at about three o'clock in the afternoon. I just stuck ND filters on the camera when it was bright and took them off when it was dark."

Working primarily with a Moviecam Compact, Pratt outfitted the camera with his favorite set of old Cooke Series 3 lenses. To soften the razor-sharp images produced by the 5298, the lenses were fitted with black, 10-denier Christian Dior stockings. "Modern stocks are so sharp that if you're not careful, the images can take on an almost video look," Pratt opines. "The stockings just soften things up very slightly."

The filmmakers varied a bit from their general photographic approach while shooting Cole's haunting dream, which gradually unfolds over the course of the story. "The dream sequences were a very high-key affair," says Pratt. "But during the grading of the film, we worked with the interpositive and internegative to almost destroy the image for the parts of the dream leading up to its resolution. We printed very light and made an interpositive and internegative which we then overexposed even more. I think the printer lights were down to about 8. When Cole finally gets to the airport at the end of the film, the look goes back to being high key, with all of the detail put back in."

Pratt points out that color was used sparingly but selectively throughout the film, to provide a series of psychological "signposts" for the audience. "Mainly, I think one could say we focused on things that had had the color drained out of them," he notes. "But the story is a complete mixture of times and places, so we did occasionally use color to cross-reference between the various parts of the film. We didn't want the audience to be entirely sure which time our hero, Cole, was actually living in. The most striking example of this is when Cole is in a kind of hospital and happens upon a CAT-scan ward where we used a really strange, black-lighty blue. That look is echoed in other parts of the film as a kind of prod to remind you that you're never quite sure which bit is a dream and which is reality. To get the CAT-scan look, we plundered our old film blue-screen cupboard and got out these old Congo-blue filters which we stuck on HMIs. It created an almost tactile sense of blue, similar to the look we used for the story's time machine.”

Plundering the Power Stations

The outmoded power stations that Gilliam and Co. located on their scouts were used as a basis for a variety of set pieces, all of which combined to provide an extensive look at the underground world of the plague's survivors. Included among the futuristic settings were a network of jail cells; a flooded, sewer-like passage that leads to the Earth's surface; a confinement area in which Cole begins to question his sanity; a high-tech interrogation room where scientists debrief Cole after his journey above ground; and an elaborate time machine that sends him hurtling back to 1996.

For Pratt and his crew, the primary challenge was to deal with the physical and logistical demands of these various areas. Elaborating on the sheer scale of the project, the cinematographer confirms, "It was all pretty frightening, really. The logistics of this picture involved controlling and enhancing the images in a situation where we had no rigs or places to put equipment. I had to call on a very good grip named Mike Miller, who had come to us very well recommended on The Fisher King; he helped us to do that film's wonderful sequence in Grand Central Station. On this project, he was able to black out 60-and 100-foot windows, build cranes that would carry 4K Xenons, and generally turn difficult places into workable, studio-like places."

Gilliam, for his part, admits that the epic scale of Twelve Monkeys caused him more than a few moments of misery. Unlike a drawing board, where it is always possible for an artist to give full play to his imagination, a film set comes with built-in restrictions. "I hate making movies!" Gilliam thunders, tongue firmly in cheek. "I wish I could give it up and get a proper job. It's non-stop frustration. You're always fighting depression, because you start with very clear ideas and pictures in your head, big plans, and every day you have to compromise because of the reality of the situation. We confronted that kind of frustration every day on Twelve Monkeys. If I have any regret about the shoot, it's that we didn't quite capture all of the power stations on film. We had to limit ourselves to what was important for the story. I hate going into extraordinary spaces and not taking full advantage of them, but to do so might have distracted from the tale we were trying to tell."

Gilliam's caveat to the contrary, most viewers will be more than a bit impressed with the film's corrosive dystopian vistas, which offer a new twist on the screen-filling Orwellian future-scapes of Brazil.

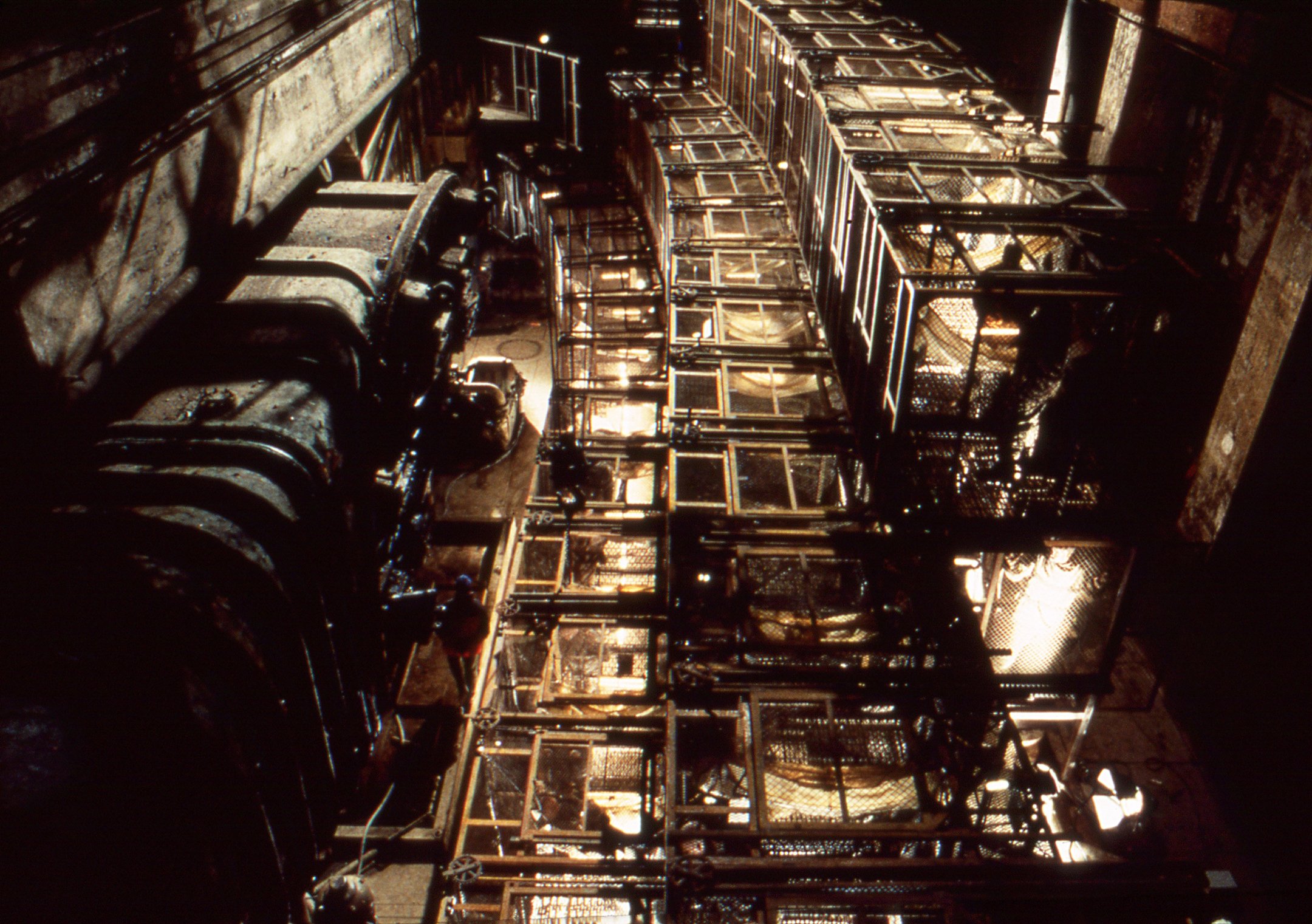

Maze of Cages

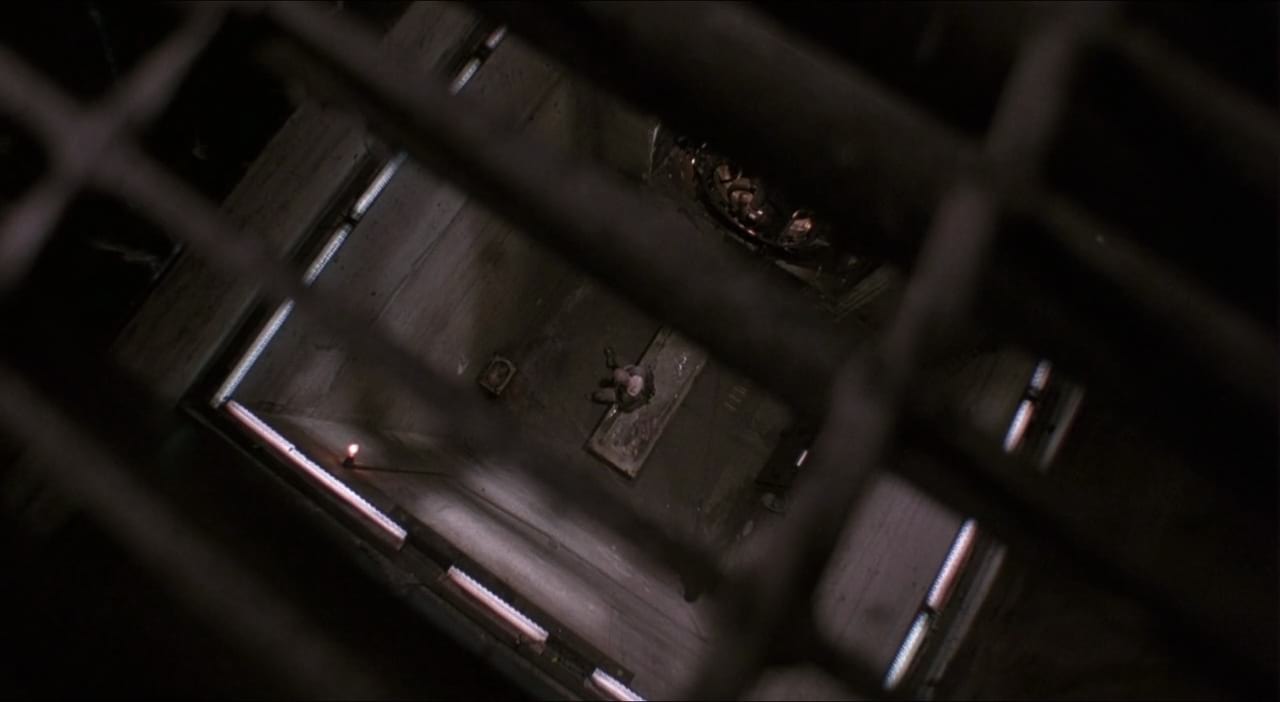

Before being sent on his fact-finding expedition, the convict Cole spends his time languishing in an 8' x 12' jail cell within a maze-like prison of the future, which production designer Beecroft designed to resemble a collection of human-sized "hamster cages." Set one on top of the other, like children's blocks, the cages were built in a well-like area in the Richmond power station. Roughly 100 feet high and 80 feet across, the space offered a series of walkways that provided a place to set up lights.

"Jeffrey constructed a row of about 10 cages which were then replicated in forced-perspective versions that went off 'round the corners to provide a sense of depth," says Pratt. "We built three levels of those, and in the final film they were augmented digitally by Peerless Camera Company, the special effects outfit that Terry formed some years ago with Kent Houston, the film's visual effects supervisor.

"The walkways were about 60 feet up, and we used them to support the Xenon searchlights featured in the sequence," Pratt explains. "On the upper story, out of shot, we added 20Ks that gave us a backlit definition through the cages. Then Crispian Sallis suggested to me that we could emphasize the perspective by placing small neon practical lights within the cages themselves. We also added luminous 2K blondes underneath the cages to underlight the various characters in their cells. Those gave the scene a really good feel."

Flood Lighting

When Cole is plucked from prison and sent on his assignment, his path from the sealed underground world to the surface takes him through a vast sewer-like corridor. The space was created by flooding an area of the Delaware power station that had formerly housed turbines similar to those at the Richmond site. The generating station's basement was actually below river level, and the space had regularly been flooded with river water during its operational period. Though it hadn't been done in years, the flood gates were opened once again to create the eerie passageway to the snowbound outside world.

"Spending winter in Philadelphia in a flooded power station is pretty difficult work," Pratt testifies, his voice leaden at the memory. "The entire crew suffered from the cold. We had intended to enhance some of that sequence digitally, but the images were so strong that we didn't need to do it. Our primary goal was to call attention to the length of the power station and give it a sense of scale. It was a pretty huge place anyway, but we let the back go black, and we threw some shadows along the sides to help create the feeling that this tunnel went on forever. We had about four Xenon lights, and the rest of the fixtures were 12Ks. We didn't have a Musco Light, because we couldn't get it anywhere near the set. Instead of covering up the location, we allowed soft toplight — real daylight — to filter down through skylights that ran the length of the ceiling, every 50 feet. I could control the amount of light coming down, and it gave me some ambient fill. It was almost like shooting day-for-night, but [the toplight] raised the basic exposure. We did experiment with reflections on the water, and there are a few in the film, but the architecture was pretty complicated, and when we complicated it more with dappled light, it seemed to ruin the scale."

Eternal Night

One of the film's most eye-catching sets was dubbed "Cell Eternal Night," an isolated room in the underground where Cole, returning from a time-machine misfire, begins to wonder if he is actually experiencing this strange re-entry ritual, or if he is suffering from delusions. The scene was played out in a tungsten-based, enclosed 10'-square, 30'-high concrete chimney that was completely blacked-out. To reflect the character's unstable mental state, Pratt worked closely with camera operator Craig Haagensen, who plays an integral role in Gilliam's English approach to the decision-making process. (In the British tradition, directors consult with both the operator and the "lighting cameraman" on matters involving cinematography.)

"The chimney cell was an extremely difficult location," Pratt attests. "It's a wonderful sequence, echoing the kind of paranoid state Cole is in. Craig did a lot of the close-up work by hand. We were shooting at the bottom of this 30-foot shaft with a roving, handheld, dutched camera outfitted with a 10mm lens. Sequences such as this were one reason we used the Moviecam, which Craig could hold for a long period of time. We were intending to do a lot of handheld stuff, and the Moviecam has an orientable viewfinder which allows you to work from either side of it. It was easily converted to [handheld] mode, and it allowed me to use my Cooke Series 3 lenses.

"We were trying to capture the look of a man in some kind of internal torment, and my job was to make sure we saw what was happening on his face. The trick was to survive each shot, carefully keeping the mood but adjusting the lamps as much as I could. The camera was observing Bruce Willis, but it was also seeing everywhere at once. For much of the sequence, I actually followed Craig around with some fill, whether it was just a small, battery-operated lamp-head or a lamp-head with a piece of white card. The look involved simple stuff like that, plus top light filtering down. We didn't often see the top of this tube, which helped, and there was also one part of the set that we could hide small lamps behind. Basically, we lit the scene with 5Ks, mini-Moles and some other small fixtures."

Elaborating upon the wide, dutched look that Gilliam favored not only for this sequence but throughout the film, Pratt says, "That strategy was particularly effective in the chimney cell sequence. Dutch angles can often be annoying or noticeable, but Craig was very clever in making them organic to the entire picture. We also used wide angles throughout the picture, but Terry frequently shoots close-ups on a 17mm lens, so our use of wide angles doesn't stick out as much as it might in a normal film, where you'd be shooting close-ups on a 70mm lens. Terry is not in the business of doing those kinds of glamour shots. Our primary range on this picture was from 10mm to 17mm! We very rarely put the 5:1 zoom on the camera, and I don't think we used anything longer than a 100mm lens. Basically, the wide angles we used were all part of the general thrust of the film. It's a difficult look to maintain, but I think Terry and I have done well with it so far. Long lenses can be easier to use, but once you're into the wide angles, it can be difficult to break from that mode."

Asked about his proclivity for wide lenses and somewhat demented, off-kilter framing, Gilliam emits a wry laugh. "I think it's just the way I am; being an ex-cartoonist, I see things in a slightly grotesque way, and wider lenses tend to capture that viewpoint. I like the distorting effect, and I like the way a wide lens bends architecture and forces perspectives; things look deeper, and the scale of things is altered. I also like what it does to people.

"My visual fetishes do make things a bit hard on Roger and the crew," he concedes. "If you're shooting with long lenses, as most people do, you can put lights anywhere. Because Roger and I have worked together since Brazil, he's gotten very good at hiding his lights; I probably take him for granted now. It's also much easier to create a composition with long lenses, because everything is on one plane; anything you're not interested in stays out of focus. It's simpler to work that way, but I have an obsession with wide-angle lenses. We always work as wide as possible, but at the same time I don't want it to look as if we're using wide-angle lenses. So it becomes a kind of game, to see how far you can go without alienating the audience. To me, using a wide lens creates more of a feeling that you're in the film than a long lens does. The whole scenario is around you when you look through the camera."

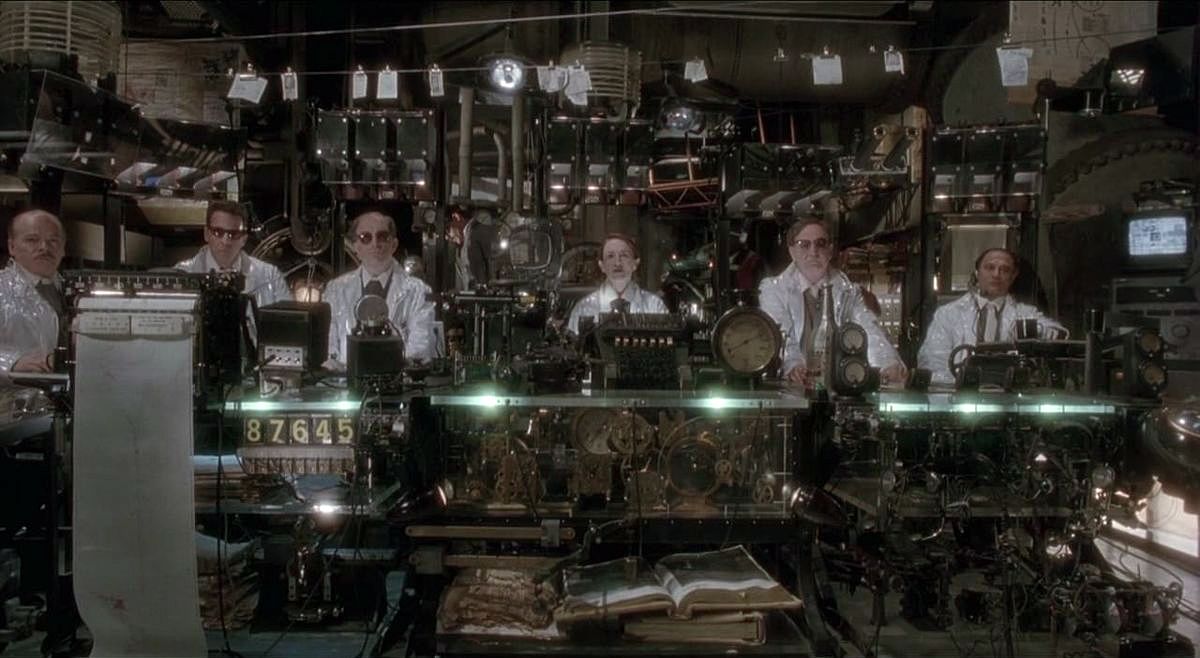

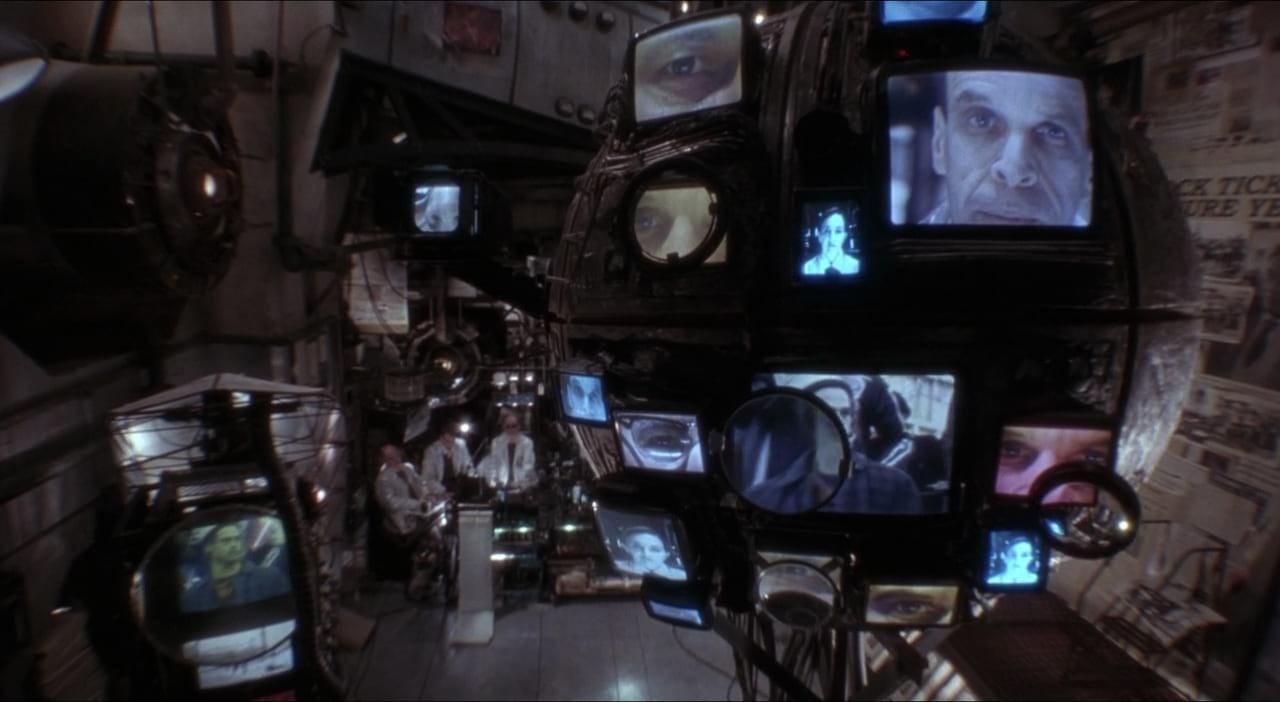

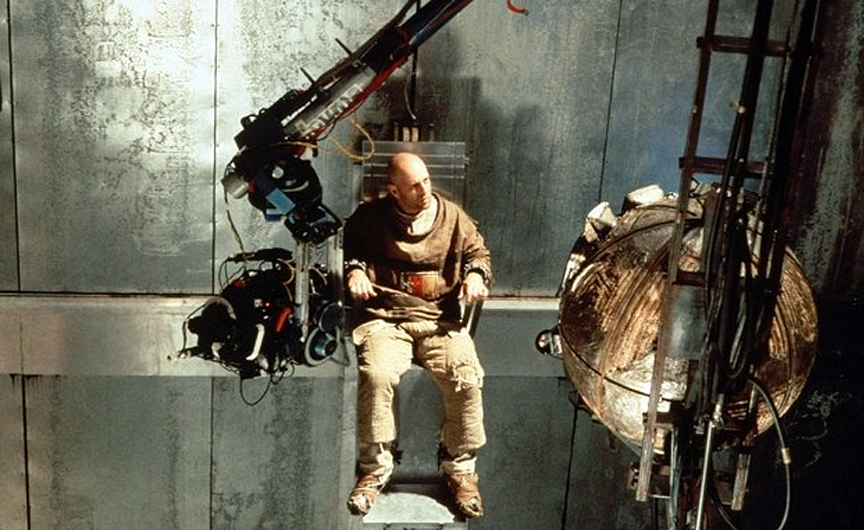

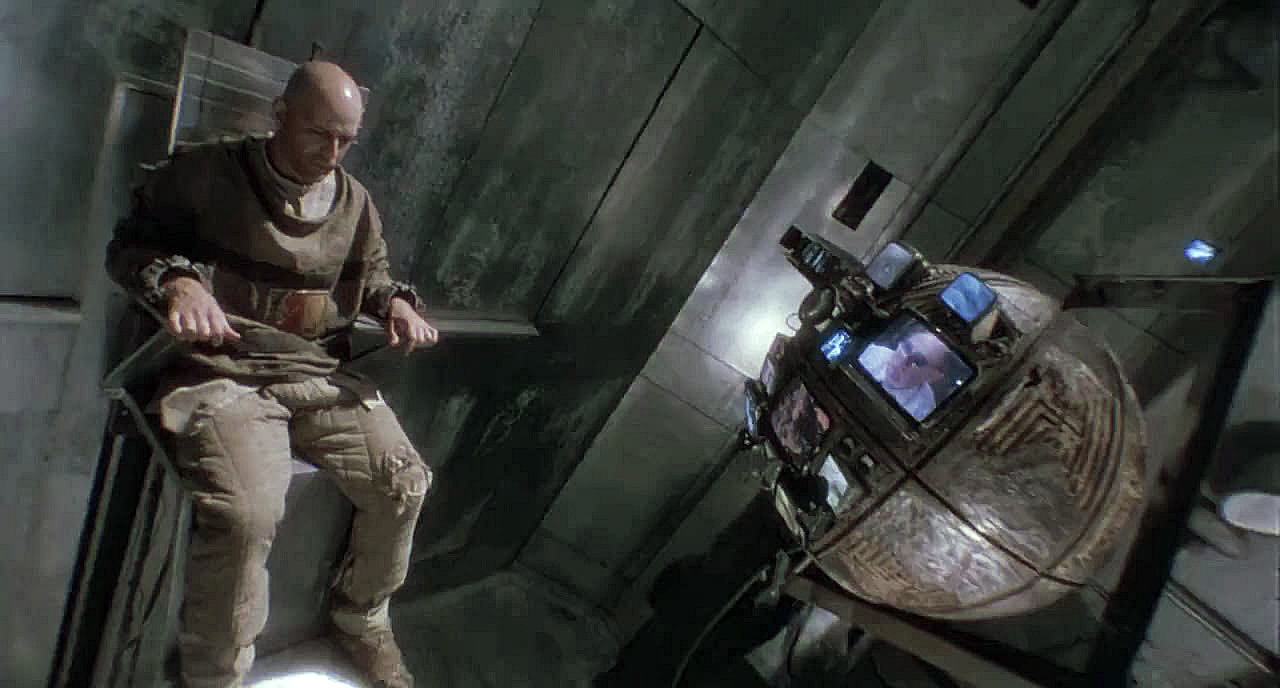

The Engineering Room

Gilliam was able to indulge his particular visual appetites to the fullest on the set of the Engineering Room, a bizarre space where the scientists interrogate Cole about his trip to the planet's surface. The scene was played out in the Number 4 turbine basement of the Westport power plant in Baltimore. Strapped into an aluminum chair that rises 12 feet off the ground along a rusty metal wall, Cole confronts both the scientists and the constantly probing Video Ball, a suspended, gimbal-mounted contraption that contains a glowing array of 15 television monitors. In addition to playing back a series of images — Cole's face, the scientists, and different slides — the various monitors also bark questions at the story's beleaguered hero. Inspired by a particularly disturbing Lebbeus Woods sketch, the ball was created via the collaboration of production designer Jeffrey Beecroft, special effects wizard Vincent Montefusco, video assist expert Ian Kelly, and electrical engineer John Schmidt. "A television screen can only be so bright, so when you go into a scene involving such screens, you have to build the rest of the lighting around it," Pratt says. "I would always think of a medium-bright television screen on 5298 stock as being around the 4 area in terms of f-stop. You have to do some testing, but I'd say it's about a 4, give or take a few half-stops. Therefore, everything has to be pegged to that level for the images to be in their proper place on the luminance scale."

monitors. Pratt found that an f-stop of 4 worked best for the sequence.

The task was complicated by the scene's other photographic requirements, but Pratt managed to solve his problems by using the ever-reliable Louma Crane. "There was a pretty solid concrete shelf above and around the set, so we could place the Louma crane on it and poke it downwards 25 feet. Terry did these wonderful probing shots with it."

With the help of practical fixtures built into the set by Crispian Sallis, Pratt was able to achieve the wide-angled shots his director so loves. "Crispian had an 'Aladdin's cave' of lamps that he had found, scrounged, hired and purchased," Pratt says. "He managed to load many of the sets with practical lamps. On another set dubbed the 'Tiny Chamber,' he had green-biased fluorescents underneath the desks in the room, 12- volt quartz lights in the seats, and 'architectural lights' on all of the machinery. It was a complete mixture, but I let that go because I knew I could light the faces with my own fixtures and get the skin tones the way I wanted them. The other lights were all in the background."

Building a Better Time Machine

The time-travel device itself (above) provided the film with a spectacular visual centerpiece that blends a real-world location with the film's futuristic scenic and lighting designs. Gilliam found his time machine during the location scout, while visiting the Richmond and Delaware generating stations. The cavernous structures date back to the 1920s and still house the rusting remnants of several enormous turbine generators that once produced hundreds of thousands of kilowatts of energy. Fascinated by the huge turbine halls and the 18- foot steel condensers within them, Gilliam decided to turn the outdated machinery into the elaborate time trigger that sends Cole back to the year 1996.

Transforming the location into a futuristic "launching pad" required intensive logistical endeavors by the crew. To create the time machine's entry tube, which was intended to resemble a CAT scanner, Beecroft's construction team cut an oblong hole into one of the corroded condensers. Once the generator area had been altered and dressed, Pratt and his crew stepped in and used their lights to sculpt an appropriately ominous ambiance.

"The time machine sequence illustrates the difficulties of shooting in a real location," says Pratt. "In addition to cutting an opening through quarter-inch plates of steel, we had to find a way to illuminate this whole structure."

Crispian Sallis once again stepped to the fore by providing Pratt with a variety of fixtures that could be incorporated into the set, thus allowing the cinematographer to avoid the task of hiding lights. "With a bit of fiddling, we could establish a basic exposure level," Pratt notes. "As far as the stop was concerned, we were generally right at the end of the zoom, which was about a 3."

As a final touch on the time machine set, Pratt installed a filtered Xenon unit in the oblong tube created by Beecroft's team. The powerful lamp created a strong bluish beam of light that streamed forth from the tube's cir¬ cular opening, illuminating the chrysalis-like gurney enveloping Bruce Willis as he was inserted into the machine.

Loony Bin

After Cole is sent back to 1996, his dire predictions about the future lead authorities to surmise that he is stark raving mad. The time-traveling convict is soon packed off to a mental institution, where he makes the acquaintance of fellow patient Jeffrey Goines (Pitt). Doubling as the funny farm was Pennsylvania's imposing Eastern State Penitentiary, whose interior offered a circular rotunda from which seven identical one story cell blocks branched.

"Terry felt that these corridors were a very strong graphic, and we persuaded the authorities to allow us to give the place a slightly 'lived in' look," Pratt recalls. "We basically had a central skylight above the area where all the action hap¬ pens, and we ringed it with scaffolding. I allowed daylight to penetrate and to change. We went for a bright, overexposed look with the faces of the patients slightly underexposed against walls and then corridors, which went off into brightly lit doors. There were three corridors on one side, and the other side was fairly darkish, like the rest of the institution's interior. We also did some night scenes in a hexagonal room we created by revamping the rotunda area and adding low ceilings.

"For the daytime scenes, we used two Xenons to create shafts of light. If the daylight wasn't good enough, or if it wasn't coming from the right direction, we projected 4K HMIs through [diffusion] frames to allow for matching. We would then scrim off the daylight and use our own lamps.

"At night, we went to tungsten. The night scenes were shot during the day, so all the windows were tented out; we would aim 2Ks and mini-Moles through the windows, and used half-85s to warm things up and provide a kind of neon streetlight effect. Then we shot 5Ks and 10Ks down the corridors, playing them off the stone floor, which created a nice effect.

Airport Check-In

While shooting the film's climax, in which the meaning of Cole's dream is finally revealed, the production team faced extensive headaches in Philadelphia's brand-new Convention Center, which was re-dressed as an airport.

"There were two areas we used in that particular location," Pratt reveals. "One was the concourse, which had windows and was open to daylight. We had to organize our schedule so that we weren't on any wide shots when the light fell, because you could see a window from just about every angle. The other spot, where the dream occurs, had to be treated differently. We did those scenes in a walkway that led to the planes. My problem was that the footage there was supposed to be high-key and shot at high speed. The actual place was lit with fluorescents, and the corridor was 100 yards long and 30 feet wide. We had to trace the end of it and completely blast that area with 4K Arri Suns to give it texture. Then we had to replace all of the fluorescents in the ceiling. Steve Litecky, a local gaffer we had signed on to help my regular gaffer, Chuck Finch, really helped us out with that. We were lighting the main concourse with HMIs, and we needed to replace the fluorescents with lights that had a coldish feel. We went with little 12-volt lamps that had a slightly dichroic reflecting surface. Banks of those were hidden near the roof within the wallspaces to light the ceiling, and we tricked things up a bit with extra lights hidden down the corridor. I had to build up my exposure so we could shoot between 96 and 120 frames per second and still get enough on the negative to print it up."

Final Thoughts

Having survived the workload of Twelve Monkeys, Pratt credits Gilliam for having the intestinal fortitude to continue chasing his ambitious screen dreams. "I think Terry really enjoys the visuals such stories lend themselves to," the cinematographer surmises. "He's an optimist, and he's got incredible energy. He's very passionate about cinema images, and I think that shows in his work. After Baron Munchausen, he got a very unfair reputation as a wild spender, but what happened with Munchausen really wasn't his fault. Prior to that, he brought in Brazil a million dollars under budget, and Time Bandits was also very affordable. At any rate, when he does spends studio money, it certainly ends up on the screen."

Addressing this same point, Gilliam notes, "This picture is also by Universal, the same company that gave me all the problems with Brazil!” Pausing to allow himself a hearty guffaw, he dryly adds, "The irony was too great for me to pass up. It seems to be very difficult to burn bridges in Hollywood."

Pondering his never-ending quest for epic imagery, Gilliam offers, "When I was a kid, I watched all of these epic films that took me to other places and other times. That's really what it's all about. 1 keep wondering why I keep making life difficult for myself, but I can't seem to help it. I need to find a challenge, to try to do something that I haven't seen before. Twelve Monkeys was an easy choice, because the script was very intriguing; I couldn't believe it had actually made it through the system. I suppose it might be much easier to just go out and do commercial films, but it wouldn't excite me in the same way."