Two-Faced Treachery: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

By breathing life into this classic tale, director Rouben Mamoulian and cinematographer Karl Struss, ASC set an eerie tone for schizophrenic chillers to come.

This article originally appeared in AC March 1999. Some photos are additional or alternate.

When it was first published in the year 1886, Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde aroused a storm of controversy. Quaint Victorian sensibilities were outraged by its premise that every human being has a demon lurking within, longing to break loose and indulge in forbidden pleasures. By scientific means, the tale’s protagonist, the kindly Dr. Jekyll, frees his suppressed self and plunges into an orgy of uncontrollable licentiousness that ends in an untimely demise.

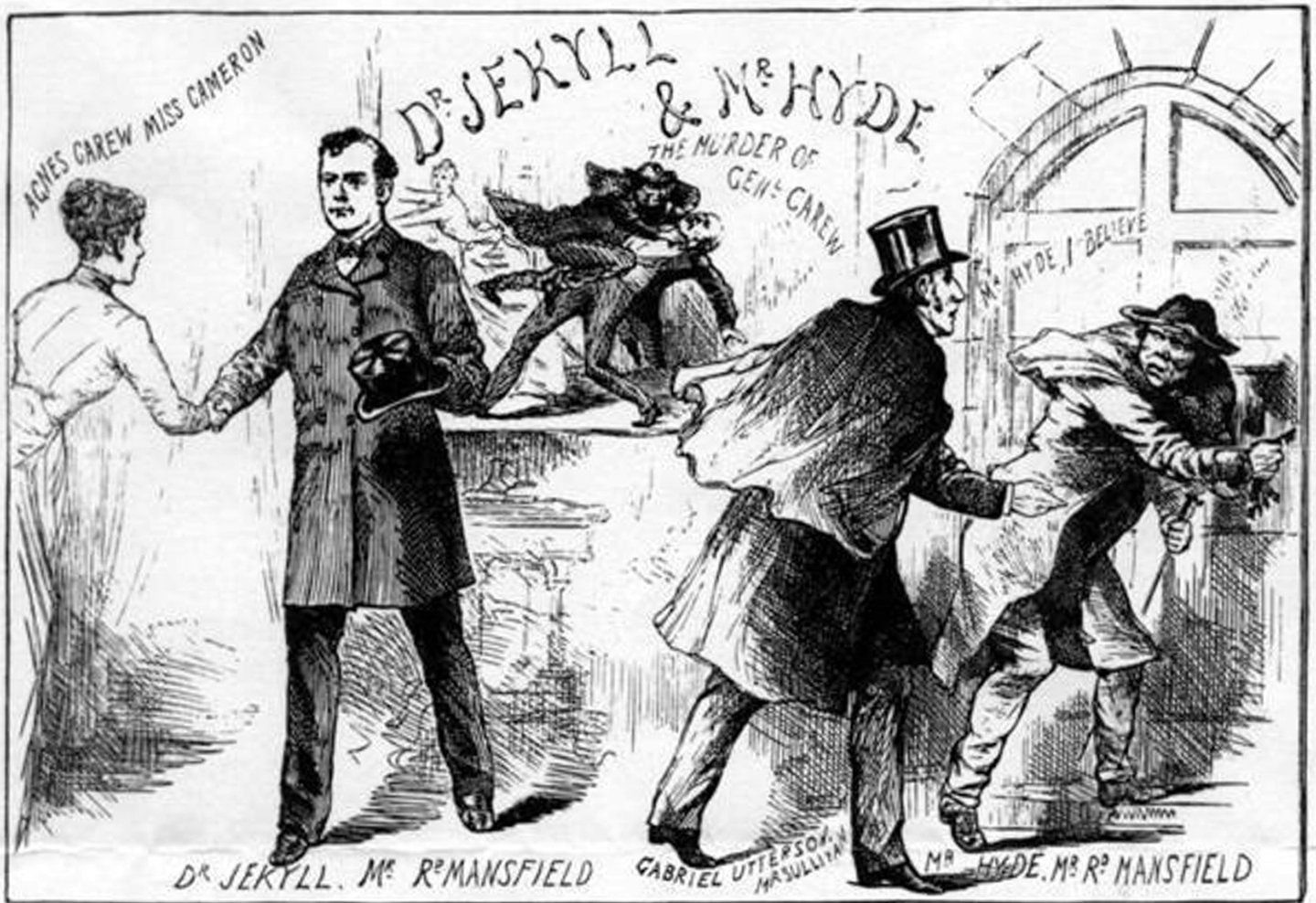

A year after the book’s arrival, Richard Mansfield staged an enormously successful theatrical dramatization of the story. In August of 1888, he brought the play to London’s Lyceum Theatre at the invitation of impresario-star Sir Henry Irving, whose manager was, quite appropriately Dracula author Bram Stoker. On August 31, however, a murder was committed by a black-hearted butcher who would achieve infamy under the moniker of Jack the Ripper. By October, three more Ripper murders had occurred. Due to accusations that the play had encouraged these heinous acts, the accomplished stage version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde play was terminated in its 10th week.

In 1908, the Selig Polyscope Company made a movie version of the Stevenson tale. Other attempts followed, including Universal’s 1913 edition directed by and starring King Baggot, which proudly introduced the “dissolving effect,” via which Jekyll transforms into Hyde in a fast dissolve. Paramount’s East Coast Studio produced the finest silent-film version, starring John Barrymore, in 1920. Spurning Stevenson’s middle-aged Victorian hero, Barrymore portrayed Jekyll as young, romantic and adventurous. This version established Jekyll’s sexual motivations and emphasized the women in his life. Again, the Jekyll-Hyde metamorphoses were accomplished via dissolves, but with improved finesse.

Spurred by the success of Universal’s Dracula in early 1931, Paramount decided to remake Hyde for the talkies. The new screenplay penned by sophisticates Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath further expanded the possibilities: Henry Jekyll, a prominent young physician, is convinced that each man contains two selves — one good and one evil.

His “blasphemous” theory that the two can be separated brings censure from colleagues and friends. Only his fiancée, Muriel Carew, understands, but her wary father postpones the couple’s impending marriage. Frustrated, Jekyll drinks the conversion formula himself. His evil self, whom he calls Edward Hyde, takes over his consciousness. Hyde makes a love slave out of Ivy Pierson, a barmaid who had aroused Jekyll’s libido, and sadistically drives her to near madness. Jekyll can no longer repress the increasingly dominant Hyde, who murders Ivy after she seeks help from Jekyll. Eventually, Hyde attacks Muriel and murders her father when he intervenes. After being cornered in his laboratory by police (who are led there on a tip from Jekyll’s former friend, Dr. Lanyon), Hyde is shot dead. As the life drains from his body, he is transformed into Dr. Jekyll one final time.

Second only to MGM in mounting expensive productions, Paramount offered John Barrymore an astonishing $12,000 per week to reprise his performance. Barrymore instead signed with MGM. By the time Paramount president Adolph Zukor chose Rouben Mamoulian to direct, he decided to cast somebody already under contract at a nominal salary — the fine stage actor Irving Pichel.

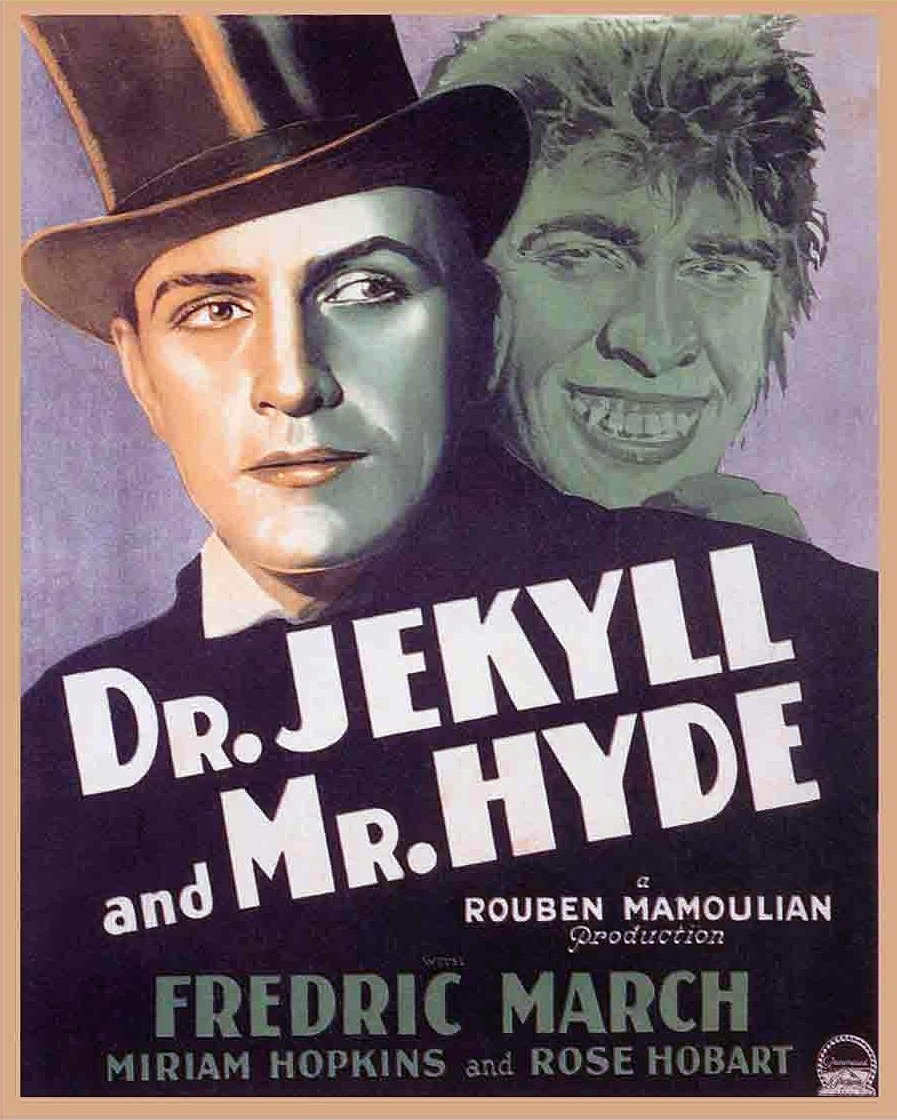

Mamoulian rebelled, insisting that Pichel would be a fine Mr. Hyde but was not handsome enough for Jekyll. He stumped for — and finally received — another contractee, Fredric March, a light romantic lead. His bosses, however, had little faith in March, despite his stage background and strong resemblance to the Barrymore of 10 years earlier.

Born in Russia’s Caucasus region to Armenian parents, Mamoulian was one of many stage directors brought to Hollywood from New York during sound cinema’s early years. He had studied at the Moscow Art Theatre and King’s College, and was internationally renowned as a director of operas, plays and musicals. Unlike many of his theater colleagues, Mamoulian instinctively grasped the possibilities of film. His first movie, Applause (1930), made in Astoria, restored camera mobility and was the first to use two channels of sound. His second, City Streets (1931), introduced the concept of having thoughts heard as voice-overs. The third, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), produced at Paramount’s studio in Hollywood, is filled with superbly realized, innovative ideas.

Paramount gave Mamoulian seven weeks of shooting time and a budget of about $500,000 — twice the cost of most A-pictures. He cast 81 actors in speaking parts: 10 principals, 30 players with more than one speaking scene, and 41 bit players with one line or more. About 500 extras appear, including some 150 each in the medical-school and music-hall sequences. A sturdy chap named Robert Louis Stevenson, nephew of the author, appears as a cockney.

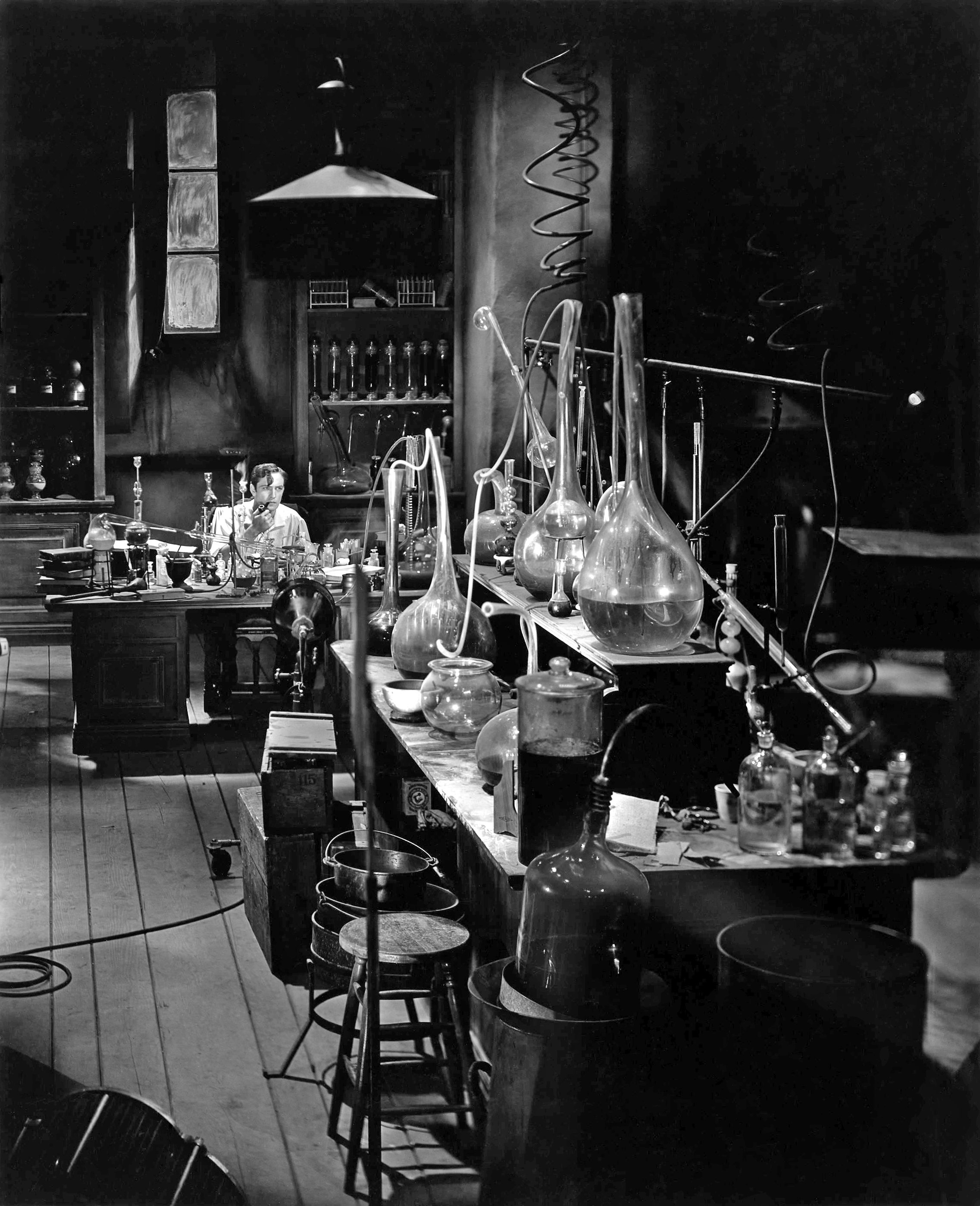

Supervising art director Hans Dreier was charged with designing 35 sets representing streets and interiors of Victorian London, including palatial homes, a medical school, a music hall, Jekyll’s fantastic laboratory and the streets of Soho. An architect from Germany, Dreier had worked at UFA during the heyday of the German art films before joining Paramount in 1923. Although his sets for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were authentic to period and country, their German-expressionist quality enhances the aura of mystery. Street settings were closed in for control of lighting, fog, rain and sound recording. Exteriors with gaslights and cobblestoned streets were built in eight separate units to allow for a greater variety of camera angles. Except for a park sequence at Busch Gardens, the entire film was shot on the lot.

Director of photography Karl Struss, ASC was a New Yorker, but no stranger to German expressionism, having won an Oscar for F. W. Murnau’s 1927 masterpiece Sunrise.

Mamoulian once described his modus operandi to William Stull, ASC in an February 1932 American Cinematographer article titled “Common Sense and Camera Angles.” He explained, “After the players are well-rehearsed, I study the action through the camera’s viewfinder, or through the recorder’s earphones . . . Most frequently, I study it through the camera, for the visual must predominate in a motion picture. It is not only the action that is important, but the way in which the camera sees that action. The cinematographer must light the action to exactly match the mood in which it is played, and must have his camera at exactly the right position matching the dramatic perspective of the scene.

“This is the salient point about camera angles: they must be used to match the dramatic angle of the scene, [and] never for their own sake...” — director Rouben Mamoulian

“This is the salient point about camera angles: they must be used to match the dramatic angle of the scene, [and] never for their own sake... If they aid the dramatic progress of the picture, they are good, and must be used; if they hinder it, they must not...

“But the use of camera angles extends beyond this. It definitely enters the realm of the psychological. It can convey the underlying significance of a scene as nothing else can. Take, for instance, a sequence from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Dr. Jekyll has just found himself transformed, involuntarily, into Hyde, with no way of returning to his laboratory to secure the chemicals necessary to return him to his real self... He is forced to call upon his friend, Dr. Lanyon, who brings the necessary potions to his own house, where Hyde is forced to use them to restore himself, changing back to Jekyll before Lanyon’s horrified eyes. In the scenes which follow, Jekyll, physically and emotionally exhausted, pleads with his friend for forgiveness. Double strength was given to these scenes by the camera angles used. Jekyll is crumpled up in a low chair, pleading piteously with his friend; Lanyon sits behind his desk, which is on a dais, as one on the ‘Throne of Supreme Judgment.’ The angles from which each is photographed subtly heighten this contrast: Jekyll is always photographed from above, looking up into the camera — an abject supplicant. Lanyon is always photographed from below, looking down at the camera — a stern and uncompromising judge. To enhance these visual contrasts, I placed Jekyll in the lowest chair in the studio, and Lanyon (already on a raised platform), on the highest, severest chair in the studio, to which I added three-inch lifts under the legs.”

The director also had very definite ideas about camera movement: “The idea that camera movement will give cinematic movement to an otherwise static scene or study, so prevalent among directors and executives, is basically false... Unjustified movement is a sign of directorial weakness, not strength... Once camera movement is decided upon as dramatically necessary, however, director and cinematographer must cooperate closely in realizing it with the utmost of technical and artistic perfection, for a badly executed move is worse than none at all. Many factors must be considered: speed, angle, and above all, rhythm. The preceding action will inevitably have established a definite dramatic (and often physical) tempo or rhythm; the moving camera scene must follow out the same rhythm, or, in some rare instance, increase it.

“Another point where cinematographer and director must be perfectly agreed is the mood of the photography which best suits the picture... Some demand photography that stresses the romantic elements — soft, delicate pictorialism. Others, like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, demand virile, realistic, almost brutal treatment. Of course, realism does not connote any abandonment of the principles of composition or lighting, but it does signify an abrupt departure from more conventional prettiness. To my mind, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde gained force from the fact that both Karl Struss and I were early agreed that realistic, harsh photography was best suited to it. Karl’s treatment of it at once heightened the realism of the central characters and threw the character of Mr. Hyde into sharp contrast by ruthlessly exposing its unreality. Let me also pay Mr. Struss a richly deserved tribute for this achievement, for the complete bouleversement of his usual artistic style revealed him to be an artist of the highest caliber.” [Struss was famed for soft-image photography achieved with filters and diffusion.]

Camerawork is used to create audience identification with both Jekyll and Hyde. The good doctor is introduced while observing himself in a mirror, preparing for his lecture. Jekyll’s journey to the medical college, the welcoming of his colleagues, and his ascent to the dais are shown from his POV, and we see his face again only as he delivers his speech. The first-person camera is also employed when Jekyll first morphs into Mr. Hyde, and during a scene in which he plays Bach’s Toccata and Fugue on the organ.

At various junctures in the picture, an inventive use of long dissolves retains ghostly imagery of one scene in the next, in order to convey the notion that the former event remains in the doctor’s tormented mind. Thus, Muriel’s face holds well into the sequence of Jekyll walking with Lanyon. After Jekyll’s erotic encounter in Ivy’s bedroom, the parting visual of her bare leg swinging from the bed remains for some 25 seconds while Jekyll good-naturedly parries Lanyon’s rebukes.

A similar application is made of diagonal and vertical transitional wipes, which pause halfway to let opposing scenes play simultaneously — such as separate shots of Ivy and Muriel, the two women Jekyll desires.

Mamoulian and Struss could never agree on Hyde’s physical appearance. Stevenson’s Hyde is “pale and dwarfish,” younger, smaller and more athletic than Jekyll (who is 50), and completely unlike him in bearing. A witness remarks, “There is something wrong with his appearance, something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why. He must be deformed somewhere — he gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point. He is an extraordinary-looking man, and yet I really can name nothing out of the way... I can’t describe him.” Another is unable to explain the “hitherto unknown disgust, loathing and fear” that Hyde inspires. “The man seems hardly human — something troglodytic... or is it the mere radiance of a foul soul that thus transpires through, and transfigures, its clay continent?” Only Dr. Jekyll knew that this beastly quality arose “because all human beings, as we meet them, are commingled out of good and evil. And Edward Hyde, alone in the ranks of mankind, was pure evil.”

Mamoulian favored a “troglodytic” countenance for Hyde. He told AC, “I wanted a replica of our ancestor, the Neanderthal man that we once were, to show the struggle of modern man with his primeval instincts.”

The director always refused to explain the methods used in filming March’s transformation sequences. In Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Darien House, 1975), which reproduces all of the film’s scenes and dialogue, Richard J. Anobile notes that “Mamoulian has yet to divulge what lights and makeup he used for the effect, but no doubt it was accomplished with infrared light.” [Author’s note: bad guess.]

Struss, however, spoke quite freely on the subject. In a 1976 dinner conversation at the ASC Clubhouse, he admitted to a disdain for the idea of Hyde looking “like a monkey. It was terrible. Jekyll’s change should have been mostly psychological, a mental rather than a physical change, with subtle makeup.

“The first time Jekyll changed, we used a technique I had devised years before to show the healing of the lepers in Ben-Hur [1926],” Struss explained. “Everybody was using orthochromatic film then, which reproduced reds and yellows as black, and gave blue-eyed actors ‘fish-eyes.’ I had begun using panchromatic film, which is sensitive to all colors. The leprosy spots were red makeup, which registered when shot through a green filter, but when we gradually moved a red filter over the lens, the makeup disappeared. The Hyde makeup was also in red and didn’t show at all when the red filter was on the lens, but when the filter was moved down very slowly to the green, Mr. Hyde appeared.”

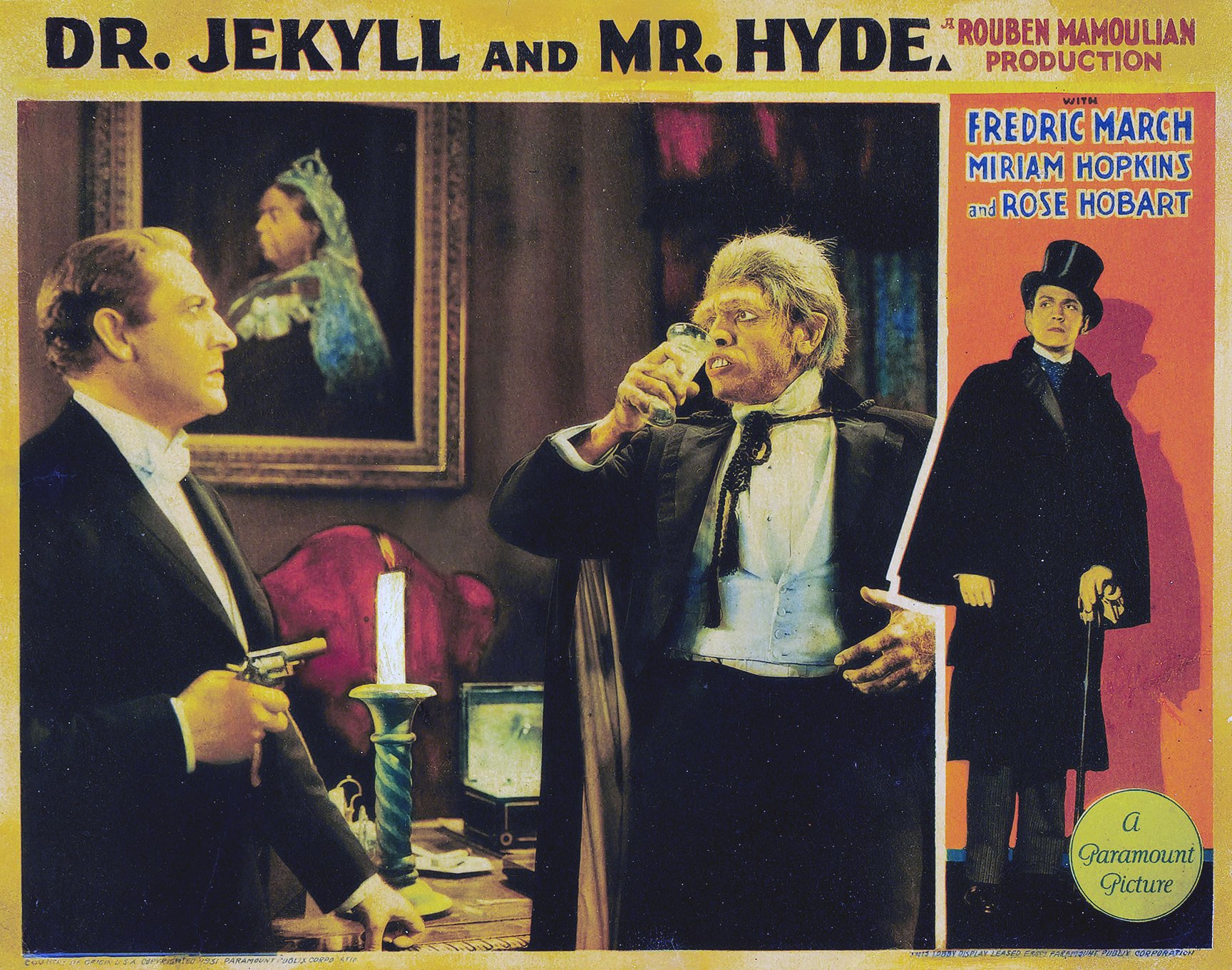

The six Jekyll-Hyde transformations in the film are all visually distinct from one another. Hyde’s guise changes each time. He first appears as a man of slight but strong build, with a brutal yet sensuous, definitely human face. In each succeeding metamorphosis, he grows larger and more animal-like, with increasingly fanged teeth, a broadened nose, more pronounced brows and rather profuse hair growth. These subtle alterations keep Hyde’s appearance from becoming too familiar, thus maintaining the impact of the transformation.

In the first malevolent makeover, the camera focuses on Jekyll’s reflection in a mirror from the physician’s POV. As his hand lifts a glass into the scene, the focus changes to tilt towards camera. Jekyll moves closer and suddenly becomes wracked with agony. The doctor clutches his throat as his hands and face darken, his nostrils widen and signs of degeneracy manifest themselves. He falls to the floor, and the room starts to spin. (Actually, the camera was whirled about while an assistant rode on top to rack its focus.) The rapidly dissolving faces and voices of Muriel and the accusing Carew and Lanyon are swept aside by visions of Ivy as he last saw her — in bed, her bare leg swinging over the side as she murmurs, “Come back soon . . . come back, come back, come back.” The camera returns with Hyde peering into the quicksilver pane, where he sees his new face.

Mamoulian devised an innovative use of sound to enhance the first transformation. The director described this sonic novelty to Raymond Rohauer during a 1967 tribute to the director at New York’s Gallery of Modern Art: “The transformation, obviously, was not a realistic phenomenon . . . yet it had to be made convincing to the audience. Now, photographically we had many ways of doing it — through the camera revolving around its axis in a kind of vertigo, the distortion of images, double and triple exposures. All of these were unreal. To score them with realistic sounds would have been quite ineffectual. I felt that the sound elements here had to be as unreal as the visual effects. I [therefore] decided to combine a number of sounds which cannot be heard in real life — eerie sounds of high and low frequencies, approaching subsonic and supersonic levels, photographed directly from light; soundtracks of gongs being struck, with the impact cut out and the resulting tracks run backward. Then I thought this surrealistic melange needed a rhythm, a beat. We tried all sorts of drums, but they all sounded like drums — too real. Then an idea popped into my head. I ran up and down a staircase for a couple of minutes, then put the microphone over my heart and photographed the heartbeat. Incidentally, this aural concoction became known in the studio as ‘Mamoulian’s sound stew.’”

The second switch occurs during daylight in a park, as Jekyll sits happily listening to a lark. A black cat suddenly enters the picture and lunges toward the bird, whereupon the Hyde half of the doctor’s personality is aroused. In a close-up, Jekyll grasps at his throat; as before, his hand and face begin to devolve (via the filter effect). The camera jibs down as the hand lowers (to show that both hands have changed) then follows them as they rise to cover Jekyll’s face. When he withdraws his hands, we see that Hyde’s face has degenerated further — makeup artist Wally Westmore had applied false teeth and a fright wig to the leading man.

After Ivy’s murder, Hyde reverts to Jekyll in Lanyon’s home. The turnabout is shown in close-up and employs dissolves. However, instead of the silent version’s simple method of “morphing,” a half-dozen barely perceptible makeup changes are gradually blended together. An 8 x 10 Graflex camera was mounted alongside the movie camera. The actor’s position was drawn in on the camera’s ground glass, so he could go off to the makeup chair and still be returned to his exact position. Cinematographer John P. Fulton, ASC later plied this technique in Werewolf of London (1935) and the Universal Wolf Man films.

In the fourth mutation, Jekyll is presented in profile while he spies Muriel through a French window. After he sees his hand ripen, the camera cuts to an angle behind the silhouetted Jekyll as his shoulders broaden and he sprouts six inches taller.

Cornered in his laboratory, Jekyll becomes Hyde in a series of nine dissolving close-ups that are smoother because there is little movement in the scene. The last metamorphosis — the death of Hyde — is also exposed in profile. A dozen 8 x 10 plates captured by Frank Bjerring with a Graflex were rephotographed onto movie film and connected by dissolves.

March’s doppelganger performance is a tour de force that almost amounts to a one-man show. He is featured in 218 of the film’s 305 scenes, appearing in 110 as Jekyll and 108 as Hyde. The kind and gallant Jekyll, who chafes under societal restraints, has 297 lines, including his address at the medical college. The rampant satyr Hyde, a bestial lover with murderous instincts, speaks a mere 81 sentences. When the monster first emerges from Jekyll’s laboratory into a hard rain, he joyously throws his head back to savor his newfound savagery. He indulges in malicious pranks, such as tripping a waiter, poking his cane up an old lady’s skirts and inciting a riot. Furthermore, his scenes with Ivy (Miriam Hopkins) are the essence of sexual sadism.

In a newspaper interview conducted shortly after the picture’s release, March recalled, “I tried to show the devastating results in Dr. Jekyll as well. To me, those repeated appearances of the beast within him were more than just a mental strain on Jekyll — they crushed him physically as well. In the last scenes he looked as though he already had one foot in the grave. Hyde was killing Jekyll physically as well as mentally.”

The actor experienced that torture firsthand during the excruciating makeup process. An early version of the prosthetics utilized an overall layer of liquid latex and landed March in the hospital. “I had to get up every morning at five o’clock to be at the studio at six,” March told Ed Sullivan for his June 14, 1938 newspaper column. “Wally Westmore would start immediately on my eyes. First he’d put collodion under my eyes, so that no perspiration would come through. Then he’d weight the under part of the eye with pieces of surgical cotton to force open the eyeball. The idea was that every time I talked, the eyes would open in an unnatural leer. To accomplish this, he’d attach threads from the cotton down the cheeks and tie them under my chin. As a result, every time I opened my mouth, the lower eyelid would be dragged down an inch. It was horrible at the time, but [it’s] interesting to look back at.”

A perfect complement to March’s performance was blonde thespian Miriam Hopkins, who is superb as Ivy, a tragic product of the London slums. Rose Hobart, a dynamic stage actress relatively new to moviemaking, had wanted to play Ivy, but instead was cast as Jekyll’s devoted fiancée — a difficult roleMuriel, played impressively and often in close-up. Also fine are Halliwell Hobbes as Muriel’s autocratic father, Edgar Norton as Jekyll’s faithful servant, and Holmes Herbert as Dr. Lanyon, Jekyll’s friend turned nemesis.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde opened to great acclaim on Dec. 31, 1931, at the Rivoli in New York City, and was later awarded first prize at the Venice Film Festival. March received a well-deserved Academy Award for his performance, edging out Wallace Beery (for The Champ) by only one vote — the Academy opted to give Oscars to both actors. Heath and Hoffenstein were nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay, and Struss for Best Cinematography. Certain that the he would win, Paramount sent out his portrait with the caption, “Karl Struss, who last night at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences banquet received that organization’s gold statuette for the outstanding cinematographic achievement of 1931-’32 for his work behind the camera on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a Paramount film.” Alas, the coveted Oscar went to Lee Garmes, ASC for Shanghai Express.

In 1935, Paramount submitted the picture to the Production Code Administration for reissue, and, of course, cuts were demanded. Later, MGM purchased the property for its plush 1941 remake with Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman and Lana Turner. Further cuts were made when MGM reissued the 1931 film on a triple bill with Mark of the Vampire and Mask of Fu Manchu. Now, restored to its original 98-minute length, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is available on video.

With fondest memories, the writer is much obliged to Farciot Edouart, ASC, Rouben Mamoulian Edgar Norton and, especially, Karl Struss, ASC.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.