Views On A Perspective: Look and See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry

Director Laura Dunn and cinematographer Lee Daniels illustrate the outlook of the reclusive author and activist in this unique documentary.

Director Laura Dunn and cinematographer Lee Daniels illustrate the outlook of the reclusive author and activist in this creative documentary.

“If you really want to understand rural America — middle American, the heartland of America, what people are dealing with there — it’s Wendell Berry, not Donald Trump, who can tell you what’s going on,” said director Laura Dunn to loud applause at the Sundance premiere of Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry.

The theater was packed with fans of this prolific author, Kentucky farmer, sustainable-agriculture advocate, and “prophet of responsibility,” as Bill Moyers dubbed him in one of the rare interviews Berry granted until now. Despite “hundreds upon hundreds of requests,” according to Dunn, Berry has refused to be the subject of any documentary. “He doesn’t like screens,” the director explains, who got him to read a poem for the audio track of her 2007 film on water rights in Austin, The Unforeseen. “He thinks screens contribute to the decline of literacy, deaden the imagination, and become dominant far too quickly.” The octogenarian has no TV, no computer, and has written his 40 books, including the seminal The Unsettling of America, on a typewriter.

Berry agreed to the making of Dunn’s documentary on one condition: He wouldn’t appear on film. He’d do audio interviews, read his writing, open up his archives — but he didn’t want attention on him. As he told Dunn, “I am my place. I am the people around me.”

So that’s what Dunn filmed, reteaming with Austin cinematographer Lee Daniels. While known for his longtime collaboration with Richard Linklater, Daniels has an even longer track record shooting documentaries, including The Unforeseen.

Lee, Dunn, and co-director Jef Sewell (Dunn’s husband) decided to make that limitation a strength. “Rather than making a portrait of the way the world sees Wendell, it’s a portrait of the way Wendell sees the world,” Dunn says. “It’s a portrait of his mind’s eye: what he sees, what he wants us to see.”

That’s established in the film’s title (“look and see” was Berry’s commandment to his children) and its opening shot, a Steadicam stroll through the woods. With the sound of leaves crunching underfoot and an Australian sheepdog leading the way, one has the impression of a POV of someone listening to nature. “Early on, we knew that we were going to simulate point of view,” says Dunn. And she knew the four seasons would be one pillar in the film’s structure, along with Berry’s chronology and his writing themes: community, farming, stewardship of the land, the agrarian worldview. So for each season, they did a long walk down that same farm road — uneven terrain fit only for cattle and four-wheelers. “It was treacherous,” says Daniel, who’d overseen his share of walk-and-talks for Linklater’s Sunrise trilogy. But these were long walks, not just from point A to point B. “I’ve never seen a Steadicam operator hold up that well,” he says of Spencer Meffert, who came in from Louisville for a day each shoot. “He was wearing that thing all day long.”

Production comprised five shoots from 2012 to 2015, totaling 100 hours of footage. During that time, Dunn gave birth to her sixth child, and the whole brood would come to Kentucky. “There was more family than crew!” Daniel says. “So whenever a newborn needed feeding, she’d send me off to shoot.” He had Dunn’s complete trust. As the director notes, “I think the key with Lee is to give him space.”

Unlike the documentary norm, Daniel was almost always accompanied by a soundman. Justin Hennerd (who happens to be Daniel’s neighbor) recorded sound even on Daniel’s “beauty shots,” as the cinematographer calls them (“I reject the notion that it’s ‘B-roll’”) — what would typically be MOS. “Even if it was a spider, or a dragonfly on some cattails, he would record sound,” the cinematographer says.

Like the film’s overall pacing, production didn’t rush. Most shoots lasted a week, with interviews clustered mid-day, leaving Daniel to ramble at day’s edge. One of his favorite shots was taken at six in the morning, of a pond with ducks and cattails right outside his quarters. The dew point had dropped, and suddenly “this wonderful fog developed over the water in front of our eyes,” Daniel says. “I let the camera roll for 15 minutes. That was a great luxury, to be able to let the camera roll a long time on a static shot, that seemingly you’d need only 10 seconds for.” The quiet lyricism of such shots elevates the film to a whole other plane.

It’s no surprise, then, that Daniel had Terrence Malick in mind. “From the outset,” he says, “we knew the film was going to be Malick-esque. It’s a real word nowadays! We were very influenced by his work and his relationship to nature.” That look, says Daniels, is “a particular point of view, typically with wide-angle lenses, not so wide that it’ll produce distortion, but just enough to bring in the exterior world of nature as much as possible. How can you film a tree with a regular lens? And a moving lens as well, to give a feeling of POV.”

Malick lives in Austin and executive produced both this and Dunn’s earlier film (together with Robert Redford). Daniel has known Malick even longer: “I did some astronomy work for him back in the early ’90s. We put a 35mm camera on the end of a telescope to track the moon and Jupiter. There were various constellations we filmed. We didn’t dare ask what he was using the footage for. A decade and a half later, it comes up in The New World. I was like, ‘I remember that shot!’” Daniel was young then, having shot just Slacker and one other feature. But he’d meet Malick socially, over dominoes. “We’d talk about things like astronomy and poetry and philosophy. Back then, no one knew where Terry was. He’d fallen off the face of the earth. But there he was, in this small French café in west campus, playing dominoes with a couple of friends, me included.” Daniel adds, “We learned pretty quick he was not interested in discussing movies.”

But the young cinematographer drank in the director’s work and absorbed it by osmosis. Ditto for the works of Wendell Berry. Daniel, who also writes poetry, kept Berry’s elegiac poem Santa Clara Valley in his back pocket throughout the filming of The Unforeseen, and it’s now embedded in his memory. “I’d use that as inspiration for visuals. It’s a very visual poem.”

Look & See also capitalizes on Daniel’s grounding in classic cinema verité. He’d immersed himself in the work of Pennebaker, Wiseman, et al., in film school, and singles out Les Blank for particular admiration. “I consider him one of the greatest cameramen ever,” he says. “I’m always thinking, What would Les Blank do?’ Or how would Terrence Malick do it? Those are my two big influences — and Haskell Wexler [ASC], of course, but that’s a different story.”

Daniel’s approach was very much appreciated by Dunn. “He’s a real verité artist,” she says. “He doesn’t like things to be scripted, he doesn’t like too much control. He likes to respond to the natural light and what he sees.” Shooting the tobacco harvest, for instance, “You could have filmed it like a journalist: take the wide shot, do a close-up, and tell this story,” she says. “Lee would get down behind, like underneath their feet, and follow it back and forth, so you’d end up seeing the tobacco leaves a lot more than the faces of the men working. Some of those shots are my favorites, with the light coming through these brown and green leaves. It’s very impressionistic.”

Aiming for a “painterly, poetic portrait,” Dunn wanted the image quality up to snuff. Their first shoot — an exploratory trip of just three days — utilized a JVC GY-HD750U tape-based camcorder: great for its light weight, but ultimately deemed inadequate for capturing the beauty of rural Kentucky, especially under bright sun. Sewell argued for an Arri Alexa, which was brought in for the second, third, and fourth shoots, coupled with a Fujinon 19-90mm T2.9 PL Cabrio. “That’s a pretty decent range for a handheld zoom,” notes Daniels. Steadicam shots, in turn, used a Cooke S4/i 14mm prime, and a Zeiss macro 200mm rounded out the package.

The Alexa, says Daniel, “was a blessing and a curse. It’s the most forgiving digital camera you can get in terms of exposure and all the curves and latitude. But it’s heavy, very heavy. It was something like 45 pounds. We had to put a bunch of big batteries on the back, so consequently I could only last so long.” By the fifth and final shoot in 2015, the Arri Amira had come out. “Thank God!” says Daniel. “That was a game-changer.” Not only lightweight, it was well balanced. “The beauty of the Amira is that it has all these adjustments, so you can balance it perfectly for your body geometry: shoulder to neck, elbow to wrist. You can tailor it to the operator’s size and physical ability and everything.”

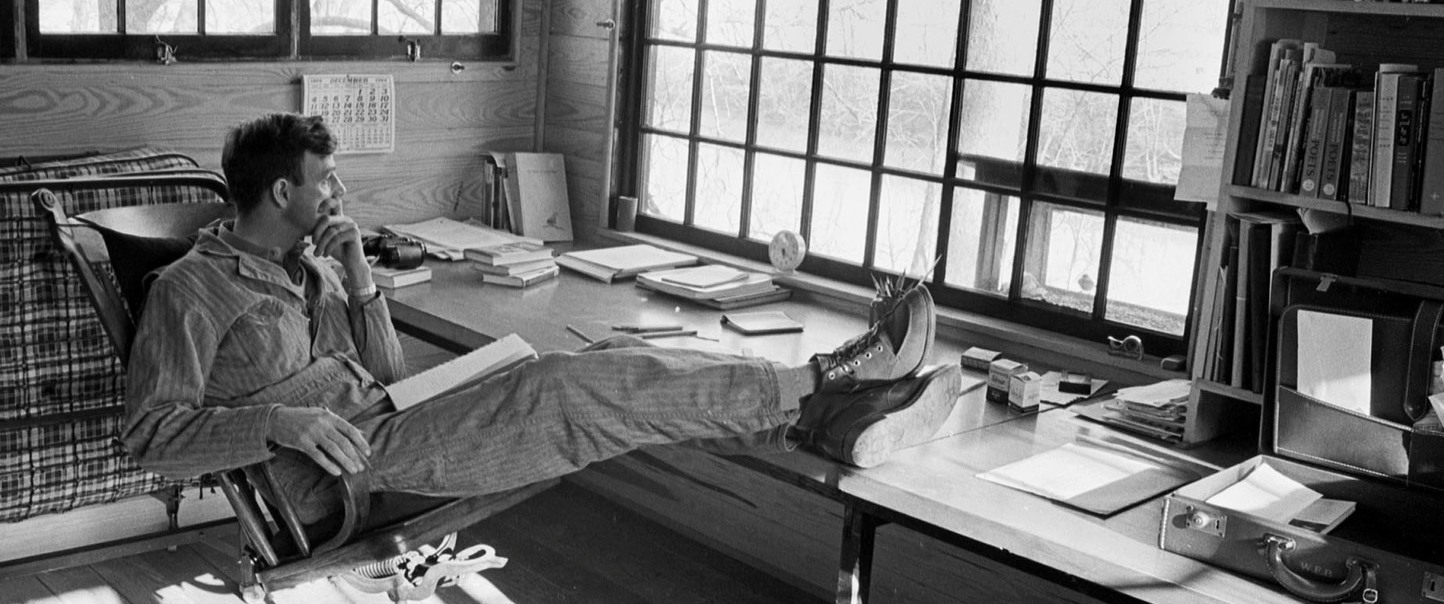

Archival stills from two great photographers were interwoven with the new footage. Writer-photographer James Baker Hall had been Berry’s best friend since college, and the University of Kentucky, where Hall taught, had an archive of thousands of unpublished negatives of Berry, his family, and life on his farm in the 1970s. “When we had that, I said, ‘Now we have a film,’” Dunn states. Daniel agrees. “That, to me, was the motherlode,” he says. “They used it perfectly in place of Wendell Berry being on camera. I think the film is much stronger because of it.” Additional stills came from David Peterson, a Pulitzer Prize-winner for his coverage of the farm crisis in the 1980s. “Originally, Wendell’s absence was a hindrance,” Daniel continues. “We thought, ‘What are we going to do?’ It worked itself out organically. Laura should be happy with it. I sure am.”

Of all the documentaries he’s ever shot, Daniel feels most personally connected to this one. Growing up in Texas, he’d go out camping, fishing, and hunting. As an adult, he owns a three-acre ranch with a stream running through it, complete with snapping turtles, foxes, and birds. Now he’s trying to acquire land outside of Albuquerque, since Austin, in his view, has become too crowded. As a poet and outdoorsman, he relates to Berry, “a giant” he’s admired for years. “There’s no other film where I felt more... like it was a noble thing, being part of it,” Daniel says. “In my mind, if I don’t make another movie after this one, that’s fine. It meant a whole lot to me.”

This unique documentary is currently screening in select cities. Check here for details.