Watching in Horror: Censor

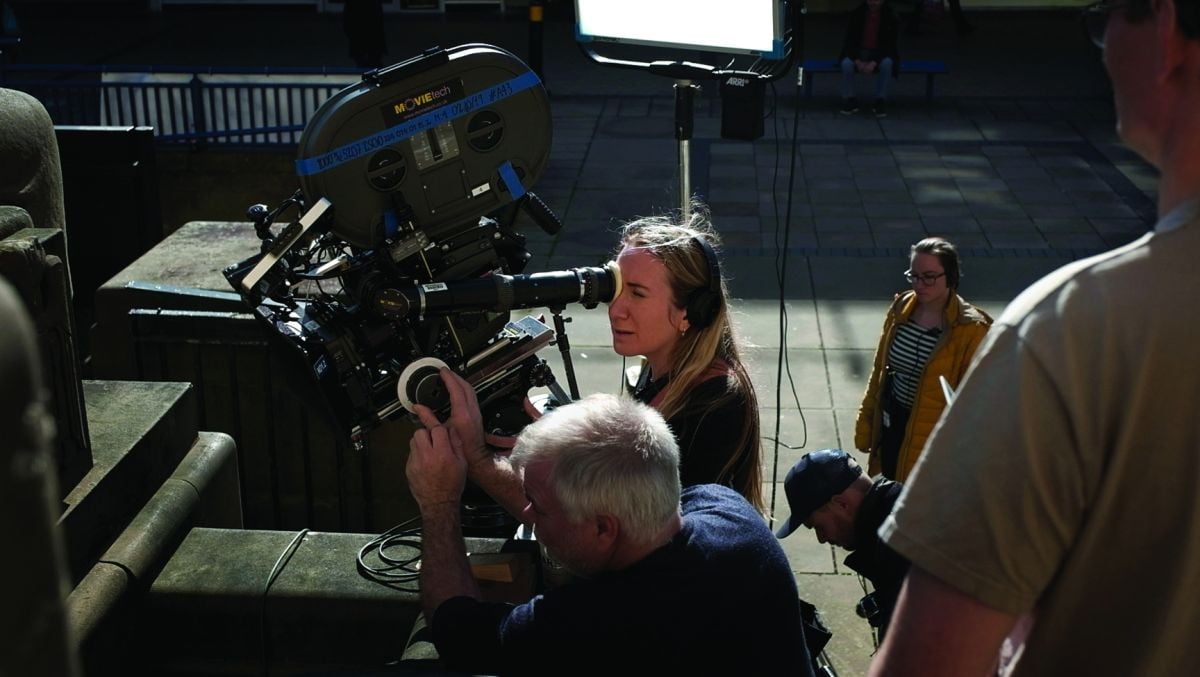

Cinematographer Annika Summerson helps re-create 1980s horror-genre visuals.

Photos by Maria Lax. Photos and film images courtesy of Magnet Releasing

Extreme close-ups of shadowy eyes under hard light feature prominently in a U.K. horror flick about a young woman who discovers that the old hotel she’s inherited sits atop a gateway to Hell. The movie is called Asunder, and it doesn’t actually exist — rather, it’s one of several fictional clips that appear in Censor. These clips, along with the actual feature, were shot by Annika Summerson and directed by Prano Bailey-Bond.

In the 1980s, a number of low-budget horror and exploitation films were distributed on videocassette in the United Kingdom as a means of circumventing the British Board of Film Classification’s strict obscenity laws for theatrically distributed films. Public and political fear over the availability of such films to impressionable children prompted social advocacy groups and court prosecutors to target individuals and businesses distributing these movies, which came to be known as “video nasties.”

Parliament passed the Video Recordings Act in 1984, closing the videocassette loophole with stricter laws on content and subjecting all films seeking distribution in the U.K. to scrutiny by the BBFC. The law remains in place to this day, though its definition of obscenity has been relaxed.

Censor focuses its lens on Enid (Niamh Algar), a dedicated BBFC film censor who harbors a deep well of guilt and psychological trauma after the mysterious disappearance of her younger sister during their childhood years.

“I grew up in Sweden, so I knew nothing about the video nasties until a few years ago,” says Summerson. “Prano knows everything about them, and we also lived together for four years, so I received quite an education.”

The two filmmakers met in 2003 while studying film and television production at the London College of Printing — now the London College of Communication — and formed an instant rapport. However, the cinematographer says, “We actually have quite different styles — our ways of framing a shot, for example — so we often have to discuss and negotiate, but the combination of our styles creates a new one.”

The duo’s collaboration yielded a number of short-form projects, including 2015’s giallo-meets-Evil Dead homage Nasty, shot on Super 16mm and Super 8mm film, in which a young boy begins seeing his missing father in the horror films his mother doesn’t want him to watch. His search for the lost parent eventually leads the determined son inside the films themselves.

Nasty’s Super 8mm sequences make an early appearance in Censor as one of the films Enid reviews for the BBFC, among other real-life nasties like Nightmare (aka Nightmares in a Damaged Brain), The Driller Killer, Frozen Scream and Soultangler. It also serves as the basis for Censor’s main plot: Enid discovers that her parents are abandoning their search for her sister — and after viewing a particularly disturbing film where a young girl brutally murders her sister with an axe, the walls bolstering Enid’s fragile psyche start to crumble until she can no longer distinguish between fantasy and reality.

“The first films that Prano showed me before we made Nasty were Cannibal Holocaust and The Driller Killer,” Summerson recalls. “I was shocked by how cheap and unrealistic some of them looked. At the time, I was very seriously studying cinematography at the National Film and Television School, and at first I thought it was terrible craftsmanship. Then I realized the more ‘homemade’ films were clearly restricted by their budgets, and are actually quite innovative.”

Summerson concedes that there are plenty of beautifully shot video nasties, but the filmmakers’ interest skewed toward films that were a bit rougher around the edges. She explains, “We didn’t want to end up with a film that looked cheap and trashy. We wanted the films within Censor to have a video-nasty feel, like we had no money or experience to speak of. We also had a lot of discussions about how to avoid going too far with it and ruining my career!”

Almost the entirety of Censor was filmed with Arricam LT and ST cameras, shooting 3-perf 35mm on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 and 250D 5207 stock. Vintage Canon K-35 lenses provided an aged, low-contrast look that Summerson felt suited the movie’s world and the period, while certain scenes called for the use of Tiffen Pearlescent and Soft FX filters. “Shooting 35mm film was right for the period we were trying to portray, and also because the subject matter involved filmmaking,” Summerson explains. “Celluloid has a texture and a gentleness that is hard to re-create on digital, especially in the highlights. On digital, I always end up adding grain in postproduction to get closer to the film look, anyway. Maybe it has to do with the period I grew up in, but there is something magic with 35mm that is hard to put into words. It’s a feeling more than anything.”

Photos of beleaguered working-class Brits in photographer Paul Graham’s renowned book Beyond Caring inspired Censor’s palette and costumes, imbuing them with a sense of social realism. “We didn’t want to portray a colorful, pastel-y ’80s,” says Summerson. “We were trying to mirror the political atmosphere of the Thatcher era — an environment where social hysteria can ignite.”

The film that triggers Enid is called Don’t Go in the Church, and it’s one of the handful of video nasties that Summerson and Bailey-Bond made especially for Censor. It’s also one of the more traditional-looking nasties — with an atmosphere of dread that pays homage to the 1974 American film Lisa, Lisa (aka Axe, photographed by Roger Corman regular Austin McKinney) and visually referencing 1971’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (photographed by future BSC member Dick Bush). “We copied the muted color palette and soft, naturalistic lighting from The Blood on Satan’s Claw. We wanted more of an everyday look — not so over-the-top, but still vintage and retro, almost like French New Wave,” says Summerson, who used a combination of Arri SkyPanels, Fresnels and Source Fours, all sourced from ProVision, to light the nasties and Censor’s main story. “It’s a fairly common look that’s linked to English social realism — like if you wanted to tell a story that’s about working-class hardship. You want it to look real, to almost have a documentary feel to it, for the audience to perceive it as reality.”

Lighting “badly” proved to be a challenge for Summerson. “Your inner DoP doesn’t really want to give in to that,” she says. “You want it to look bad, but it has to be bad in the right way.” She created slashes of hard lighting with Source Fours, adding splatters of color with Lee ¼ CTS and Light Lavender gels.

Another of Censor’s homages, the aforementioned Asunder, is based on Lucio Fulci’s 1981 film The Beyond (aka 7 Doors of Death, photographed by Sergio Salvati). The filmmakers chose to mimic Fulci’s editing style and shot compositions. “We also looked at the camera movement,” Summerson adds. “We didn’t want ours to seem too advanced, so instead of moving the camera intuitively, we kept it out of sync with the actors.”

By way of example, she describes how an actor would “deliver his line, then wait for the camera to move, and then begin to walk after the camera had already started. As a camera operator, you have to fight your instincts and focus on the rules you have set out for yourself instead.”

The cinematographer intended to shoot the nasties on 16mm, but budgetary restrictions prevented the production from renting an additional camera body, so interiors were photographed on uncorrected 5207 daylight stock, pushed one stop to enhance the grain and contrast.

The rest of the original media that appears in the film claims no direct outside visual influence. Extreme Coda features a brutal rape scene that was thematically inspired by I Spit on Your Grave (1978), but was designed and photographed in a way that would emphasize the set’s unique qualities — specifically, the wallpaper — so that Enid would recognize it when she later visits the home of a sleazy horror producer.

For a clip that appears on a screen in a viewing room, Bailey-Bond performed a brief cameo as a woman drenched in blood (actually tomato sauce), stabbing a huge knife at the camera. “We originally shot this on an old VHS camera we found in an attic, but it didn’t work properly and the footage was ruined, so we captured it again on an iPhone 11,” Summerson says. Additional grain was applied to this material during the final grade, as were further adjustments to make it pass as older footage. “We also shot all of the news segments,” the cinematographer adds. “Those were done before principal photography, using a Panasonic M40 VHS camcorder with shoddy zooms and intentionally average framing.”

Censor is presented primarily in a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, which was achieved by cropping the top and bottom of the spherically derived frame, though it dynamically shifts at points when Enid loses her grip on reality. (The filmmakers also employed this technique in Nasty.) For example, when Enid ventures into the woods to find the mysterious director of Don’t Go in the Church and Asunder — as she believes her missing sister is acting in his latest production — her perspective gradually squeezes down to a pillarboxed 1.33:1 frame.

“We wanted to blend the two worlds together, to bring the audience into the video nasty along with Enid, [so they would wonder], ‘Are we in her mind, or are we in reality?’” says Summerson. “As a technique it can be leading, but as long as you take a balanced approach it can still be very effective.”

As Enid spirals further into madness, Censor employs ever more imaginative in-camera effects: gurgling impalements, sucking chest wounds with talking heart puppets, and spurting decapitations. “We wanted the effects to be of the quality of old-school horror,” Summerson says.

At the movie’s climax, Enid’s psychosis becomes complete as she imagines a scene involving her parents and her lost sister, which plays out in front of the family’s childhood home on an idyllic street in Leeds. Two versions of the day-exterior scene were shot on 5207 daylight stock: a beautiful, colorful fantasy enhanced by Tiffen Pearlescent and 85 filters; and a cold, harsh “screaming world” of reality, shot without any filtration. The versions were then intercut to present two jarringly contrasting iterations of the scene.

Cinelab London — which handled the film’s processing and scanning — provided dailies, which were graded by colorist Paul Dean. The final grade was performed by colorist Vanessa Taylor at Dirty Looks in London. “A lot of Censor’s look was done in-camera, and the decisions we made in post reinforced the decisions that were made on set,” says Summerson. “While we were shooting, I’d always ask, ‘Is this too much?’ But with Prano, nothing was ever too much. We were going full out.”

2.39:1 and 1.33:1

Formats: 3-perf 35mm, VHS/Digital Capture

Film Stocks: Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, 250D 5207

Lenses: Canon K-35 Prime

Cameras: Arricam LT, ST; Panasonic M40; iPhone 11