What They Had: Intimacy in Anamorphic

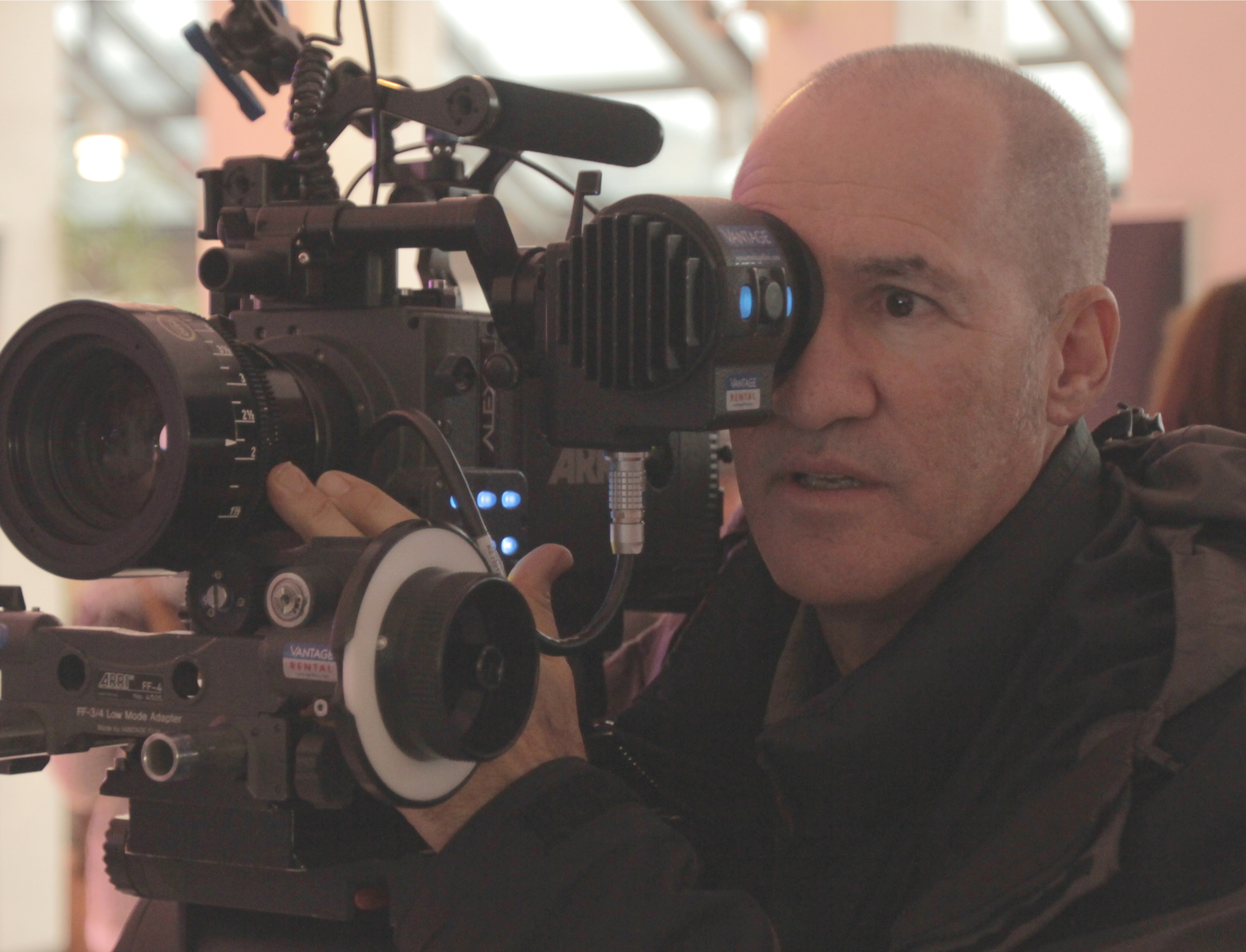

Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC discusses his subtle work in this indie drama, for which he employed a widescreen frame to visualize a very personal story.

Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC discusses his subtle work in this indie drama, for which he employed a widescreen frame to visualize a very personal story.

What They Had is the directorial debut of playwright Elizabeth Chomko, a Chicago native who adapted the personal story of her grandmother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease into a lively, heartfelt feature script starring Hillary Swank (as Bridget, a version of Chomko’s mother), Blythe Danner (as Ruth, the grandmother), Michael Shannon (gruff uncle Nick) and Robert Forster (grandfather Burt). Chomko developed the script first at the 2014 Sundance Screenwriting Lab, then as an Academy Nicholl Fellow in 2015 before going into production on the film a year later.

What They Had premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, where it was then picked up for distribution by Bleecker Street Pictures for an October 2018 release. “It’s a film about memory, family relationships and losing the people close to you while you’re still trying to find yourself,” describes director of photography Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC.

The cinematographer’s previous feature credits include Finding Neverland, The Kite Runner, Leaves of Grass, Quantum of Solace, Machine Gun Preacher, The Paperboy, The Host and the upcoming The Red Sea Diving Resort.

In the following conversation, Schaefer comments on his collaboration with Chomko and lays out their methods for bringing her memories to the screen.

American Cinematographer: Who sets the look of a film, you or the director?

Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC: You either go into your first meeting with the director with a precise visual, or you ask them what they want to see. I chose the second option when I met with Elizabeth, and she said, “I want it to feel like a memory that’s happening right now.” It’s timeless in the sense that it’s not tied to any period of time, which is why there are no calendars and maybe one clock in the whole film.

“Anamorphic takes you into the realm of cinema. It gives a bigger feel to what you’re watching.”

How would you describe the tone?

Elizabeth wanted everything to feel slightly heightened, which is why we shot with anamorphics. I would’ve shot on film if we had the money, just to make it a bit softer and more unreal.

You don’t see a lot of family dramas filmed in the widescreen aspect ratio.

Anamorphic takes you into the realm of cinema. It gives a bigger feel to what you’re watching. Whether it’s with spherical or anamorphic lenses, widescreen is good for composing multiple actors in a single shot. The thing about anamorphic in particular, and especially these older lenses, are the aberrations around the edge of the frame — they fall off, vignette, distort, flare — and Elizabeth really responded to that. To her that felt like memory — sharp in the middle, with blurry edges.

What lenses did you use?

We got the only lenses available to us, the Vantage Hawk C-Series, which are based on old Lomo glass that Vantage re-housed 20-something years ago. Alexander Schwartz at Vantage was very generous and shipped them over from Germany. The lenses are a little difficult to work with because the whole barrel turns and extends multiple inches when you focus, and because it’s spinning, you can’t attach a matte box to the front. Lawrence Daufenbach in Chicago devised a sliding matte box mount for us, first on a 3-D printer and then they milled it out of aluminum.

What camera did you have?

We had Alexa Minis, shooting ProRes 4444 Log-C. Everything came from Daufenbach except for the glass, which came through them from Vantage.

There’s one moment in particular where I really felt the affect of the lens, a really wide angle…

That’s the shot where the family is walking through the hospital after the mother has been found, and they come rushing through a set of doors into this narrow corridor...

That’s the one.

We used our widest lens, a 20mm, which is quite wide and it distorts a lot, but there’s a distorted feeling about what’s happening in the scene, and it was the only way I could fit everyone into the frame. That’s an extreme example, and it’s the only time we used that lens during the production.

Where did you shoot the project?

In Chicago and California, all on practical locations, and the car work we shot on greenscreen at my insistence.

“The cinematography isn’t supposed to call attention to itself in any way, it’s just there to draw you into the story.”

Why did you insist on shooting the driving scenes against greenscreen?

We didn’t have a lot of time or money to spend on a process trailer. Even if you have the best in the business, it’s time-consuming, and there were quite a few day and night driving scenes. On top of that, we were shooting around Chicago, and in the script there’s a snowstorm, but we didn’t have a single day of rain, it was mostly sunny and warm when we filmed in April. If we did those shots against greenscreen, we could do all the driving scenes in one day on a stage and get the snow plates later. This also allowed me to use the anamorphics, because the close focus on those is about 3 1/2 feet, so I could place the camera slightly farther away than I could if we were on a trailer.

Did you have to shoot towards the middle of the lens with this older anamorphic glass?

I tend to shoot a T2.8/4 split in general. There are times when I might go to an 8 or an 11 if I want more depth of field. I did shoot wide open for some of the night interiors, like the opening scene when Blythe leaves the house the middle of the night.

Can you walk us through your “poor man’s process”?

We had a few tungsten lights, some LiteMats and a couple of electricians who knew what to do.For the nighttime stuff I wanted to give the feeling of driving, so I put some sodium color gel on these sweeping tungsten lights overhead, used red gels for brake lights just to mix it up a little. We didn’t have a dimmer board or a mixer, but my gaffer, Dave Williamson, did have an iPad that let you chain six of the LEDs in a row and do a chase sequence, like you’re going down the street. Otherwise, it was four people sitting on ladders and moving lights with their hands.

Did you have any plates or reference to use as a guide?

We were shooting to some plates that Elizabeth had originally shot a year before in the snow. I was judging the lights by that. The daytime stuff was easier because it’s all just soft, overcast light.

One of the things I noticed about this film is that the cinematography is very low-key. It doesn’t call attention to itself.

The cinematography isn’t supposed to call attention to itself in any way, it’s just there to draw you into the story.

What was your approach to camera movement?

The movement is supposed to go with the action. There are a couple of shots where we push into a room to get closer to the characters, but it’s moving with the dialogue. Most of it was supposed to feel very natural and smooth, with slider moves left and right to add some life to the scene. It’s an emotional and lively family we’re watching. Everyone had their attitudes and humor and they were never really still. The movement helped bring that to life

“The intention was to not be overly dramatic, unless it’s a dramatic scene and the location motivates it.”

You operated, yes?

I was the A-camera operator and Erdem Ertal was B-camera and Steadicam. We used a Steadicam when we couldn’t use a dolly. By the way, all the stuff that was shot in California and a couple of the final things in Chicago — the scenes that take place in California — was shot by Anastas Michos [ASC]. I was on to another production and missed the last 10 days of shooting.

How did you make the hand-off?

Tas came to Chicago a few days before I left, and we showed him all the dailies and described the methods and the look. Elizabeth was pretty specific about what she wanted. She was always paying attention to what we were doing with the framing and the movements, even though she was so involved with the drama of revisiting these family memories.

What can you tell us about the Super 8 footage interspersed throughout the film?

There are two kinds, the really old actual family stuff that Elizabeth’s father had shot, I believe, and was transferred to VHS. Then Elizabeth also shot some Super 8 on her own to recreate the moment where the young grandparents go on their first date to the movie theater.

Your lighting is also very naturalistic; not “natural” in a movie lighting kind of way, but in the sense that there’s hard light and soft light, it’s not always flattering, and the characters move in and out of shadows.

The intention was to not be overly dramatic, unless it’s a dramatic scene and the location motivates it. There are scenes with some heightened drama, like the night exterior behind the apartment where Michael and Hillary have their confrontations, I just kept it dark and moody with a hard single light. There’s also the scene where Michael brings Hillary to his bar for the first time. Elizabeth wanted it to be completely dark inside, because Hillary’s expecting a dive, but it’s actually a beautiful bar we shot at a real restaurant in Chicago. I was able to use only a couple of practical lights when Michael is making a drink for Hillary and he disappears completely into darkness behind the bar. It’s like there’s something that she doesn’t know about him, and he’s right in front of her.

For the daytime, most of it was supposed to be overcast. There were a couple of scenes where we had to shoot outside in the bright sunshine, like when the family goes out looking for Blythe, and the Robert’s character has a heart attack. That was a sunny day, so we worked it out where we’d be in the shadow of the building as much as possible.

For the day interiors, I used a big soft light coming through the windows, and because we were turning around so much and shooting two angles, I tried to have a minimum of lighting inside, maybe some LiteMats I was able to tuck up inside near the ceiling for a little extra fill, or something behind a piece of furniture. I did have one 18K HMI and a couple of 6Ks and 4Ks, mostly either through heavy grid or bounced off muslin.

“If there’s no major shift in the story that calls for a change in the look, whether it’s the light, the camera or the color, I always try to go for a consistency.”

The family in this film is a Catholic, and the scenes in the church take on a much different vibe. The light there is warm and alive.

Most of the churches we looked at [during the scout] were very dark, but the church we ended up using had a lot of natural light and we wanted to use the stained glass windows as a way to justify all the warm direct light coming into the set. The location also had a dimmer system that was available to us right on the floor. We used the presets for “wedding” and “midnight mass” for the two scenes we had, and I didn’t need to bring a whole lot of auxiliary lighting in except for the closeups, which were just some small LiteMats or Kino Flos.

Did you use any filtration?

Whenever I’m shooting digital, I tend to use 1/8 or 1/4 Tiffen Black Satin filters for a general look to take the digital edge off the image. I also use polarizers a lot. Sometimes I’ll use Tiffen Glimmerglass for a more romantic, dreamy effect.

What kind of adjustments did you make in the color grade?

It was the end of December, right before Sundance [2018], when we did the grade at Light Iron in Los Angeles with Ian Vertovec. I had five days to do it, but the dailies grade had pretty much gotten us to where I wanted to be, so I was just going through and making sure everything was consistent. If there’s no major shift in the story that calls for a change in the look, whether it’s the light, the camera or the color, I always try to go for a consistency. To me, it comes, I hope, as sort of second nature, just being able to let it happen that way. If it hasn’t come to me by now, it probably never will.

What They Had will be released theatrically in the U.S. on October 12.

This article was produced as part of the media partnership between AC and Canon in conjunction with the Sundance Film Festival. You'll find more of our coverage here.