Wrap Shot: In Cold Blood

Stark black-and-white photography by Conrad L. Hall, ASC added a grim sense of realism to this unsettling 1967 true-crime drama.

For the harrowing 1967 drama In Cold Blood, Conrad L. Hall, ASC re-teamed with director Richard Brooks, with whom he had successfully collaborated on the action-packed western adventure The Professionals (1966).

A triumph on every level, the film is a devastating dramatization of Truman Capote’s 1966 true-crime “nonfiction novel,” which details the slaughter of an upstanding Kansas family by a pair of unbalanced drifters — Perry Smith (played by Robert Blake) and Dick Hickock (Scott Wilson).

“We decided to shoot in black-and-white because we wanted to make it real; we were filming in the actual locations where the various incidents in the story had taken place, including the actual murder sites, and the use of black-and-white gave the film a heightened sense of truth without making things too lurid,” Hall explained.

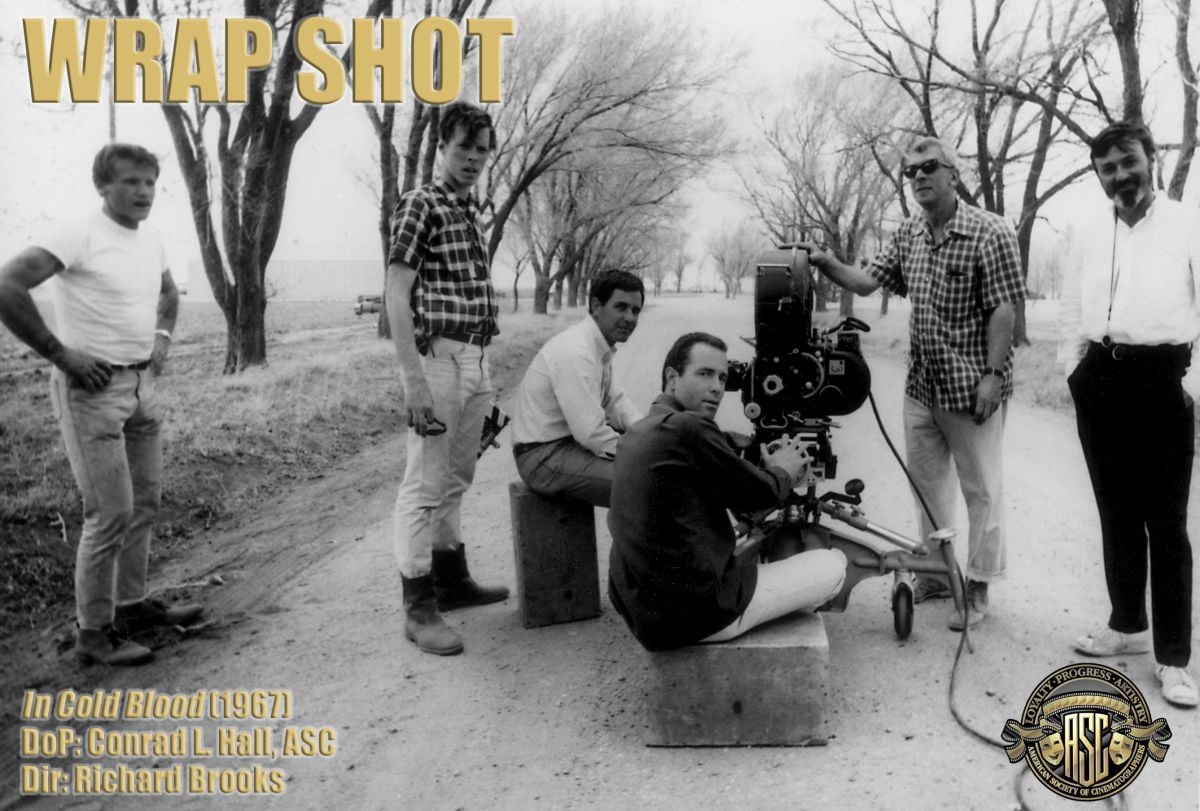

In the photo below, (from left) camera assistant Bobby Thomas (seated on apple box), operator (and later ASC great) Jordan Cronenweth, Brooks and Hall line up a shot while on location in Kansas, where the actual murders took place:

Hall’s work on this film earned him his third Academy Award nomination and the undying admiration of cinematography buffs, who now view In Cold Blood as a nearly flawless achievement. The film offers a dramatic mixture of careful planning and on-the-spot inspiration.

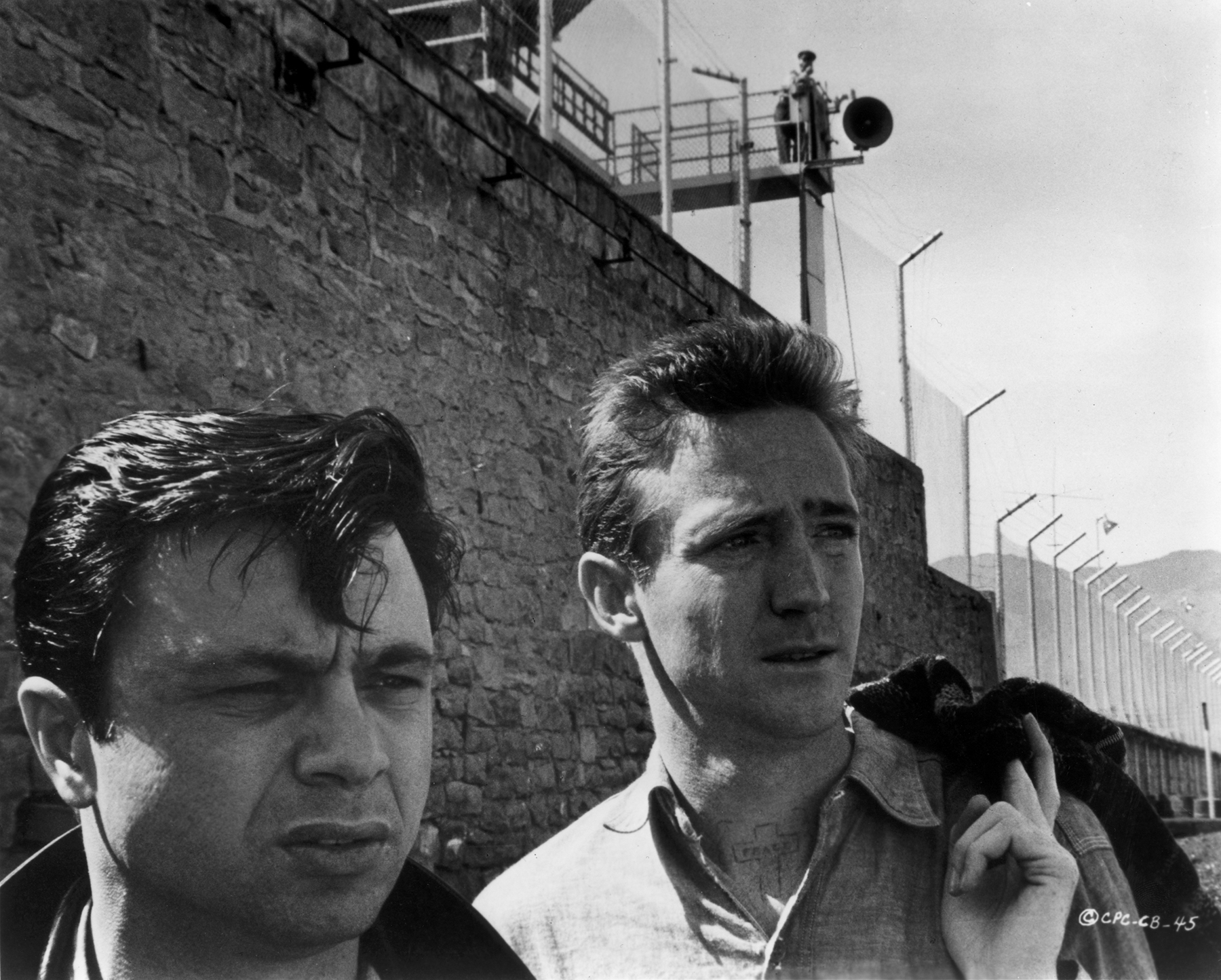

Perhaps the most famous scene in the film presents a final speech by Smith, who confides his feelings to a prison chaplain just minutes before he is executed on a rainy night. Among the many “happy accidents” Hall exploited during his career, this sequence stands alone in its brilliance. As the unemotional murderer reminisces to the chaplain about his unhappy relationship with his father, the drizzling rain outside the cell’s window is reflected onto his face, forming a river of symbolic tears (seen at the top of this page).

“It really was raining the night the two killers were hung,” Hall recalled. “The warehouse where they were hung and Death Row were two locations in which we weren’t allowed to shoot, so we had to recreate them. I wound up lighting this scene of a man about to be hanged, talking to a chaplain as rain was being created outside the window. The light from the prison yard was creating a dim, moody ambiance, and the chaplain was reading from the Bible by the light of a little desk lamp. The outside light was creating the penetration, and we used a wind machine to create some movement in the rain. But the machine blew a mist on the windowpanes, and after a certain point the mist became so heavy that it started to trail down. While I was lighting the scene, I noticed that the light from outside was shining through the water sliding down the window pane and projecting a pattern resembling tears on the face of Robert Blake’s stand-in. I brought it to Richard’s attention. In the finished scene, the acting, cinematography, direction and writing all come together to create a very memorable moment.

“People think you’re a genius for planning something like that, when in reality you were just smart enough to notice it and exploit it,” Hall related with characteristic modesty.

Noted John Pavlus when writing about the film for American Cinematographer:

Brooks invited this kind of serendipity through his insistence on filming at many of the locations where the real events had occurred: the convenience store where Smith and Hickock bought the rope and tape used to subdue their victims, the Clutter family; the courtroom where a jury had sentenced them to death after just 40 minutes of deliberation; and even the Clutter house itself, where, according to Capote, two individually affectless personalities merged into one capable of murdering an entire family “in cold blood.”

Brooks’ strategy has an especially eerie effect in the film’s theatrical trailer which boasts about the actors’ resemblance to their respective characters — and even superimposes their faces over those of the killers to prove the point. Brooks originally wanted Paul Newman and Steve McQueen to play the lead roles, but Blake and Wilson chillingly capture their characters’ deadened personalities and complementary moral bankruptcy in a way that two marquee stars might never have managed.

Whether it’s a top-lit close-up of Smith’s cat’s-paw bootsole or a daylight panorama of Hickock winking and hitching rides in the Nevada desert, Hall etches these figures into his widescreen frame with the crystalline detail of a fine lithograph. His daring use of practical-source lighting is evident in the first shot, as two white bus headlights bear down on the title card through a sea of inky blackness. When the two killers stage their midnight break-in at the Clutter home, Hall slashes the scene’s dread-soaked darkness with brutal hot spots from knocked-over lamps and moving flashlights. His contrast palette also mimics the story’s moral arc: sketchy details about the killers' troubled pasts initially invite audience empathy, but by the time In Cold Blood winds its way to gallows justice, Hall has transformed his exquisite gray-scale portrait into a grim black-and-white boneyard.