Drones Lend an Antarctic Advantage

Bringing a new perspective the docs-adventure series Whale Wars with aerial camera drones also established a new layer of security for the show's majestic stars.

Bringing a new perspective the docs-adventure series Whale Wars with aerial camera drones also established a new layer of security for the show’s majestic stars.

By Gavin Garrison

My first Antarctic adventure for the Animal Planet series Whale Wars began on December 25, 2012, when I flew across the world to join the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society — the wildlife activists on whom the show is based — and their fleet of ships at a port in New Zealand. As conveyed via a thick style-guide, my crew’s mission was to stick closely to the show’s established “docu-adventure” aesthetic that had captivated audiences since the series premiered in 2008.

That style was rough-and-tumble, with single-source, high-key interviews; predominantly handheld camerawork; crash zooms; GoPro-style POVs; and an infinite depth of field courtesy of the small sensors on which the show was birthed. As both a producer and a cinematographer on the series, my goal is to remain loyal to the high-adrenaline aesthetic that audiences have come to know and love while simultaneously pushing a look that keeps us relevant and engaging in today’s television market. And so, when I began prepping Season 10 in late 2016, I was eager to introduce some of the modern technologies that have become commonplace on other productions — specifically, 4K capture and the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), aka drones.

If you take a look at any number of today’s adventure-themed unscripted series, it becomes immediately evident how readily drones have been adopted by the genre — and how heavily they’re relied upon to provide extensive coverage. Projects like Planet Earth II have embraced drones in order to realize unprecedented shots and jaw-dropping camera moves, bringing sweeping, cinematic movement into the documentary sphere. However, I’ve also seen a trend in which shows substitute what would ordinarily be conventional coverage with a drone’s telltale high- and wide-angle view. Though the average viewer may not notice, to the discerning cinematographer, a show that’s inundated with drone footage can start to feel like shooting choices were made for convenience’s sake rather than the story’s.

For Season 10 of Whale Wars, my goal was to split the difference between the high bar set by Planet Earth II and the examples I’ve seen from other unscripted productions in our genre. Balancing utility with beauty, we would employ drones to create “cinematic” coverage to the best of our abilities, and we would use the drones’ unique perspective to capture master shots that we could default to in scenes that demanded context for the viewer — for example, if one ship collided with another at sea, or if a ship sailed through a thick field of ice. The trick, I felt, was to be discerning with our deployment, lest we give post too much to hang their hats on.

We chose to capture this season in 3.8K UHD, in part because I believe the footage has a much longer shelf life with the higher resolution. We also chose not to capture in log, as I thought log would have created a workflow issue down the line. Those decisions, though, were made in somewhat of a vacuum — as we on the production crew don’t have any communication with post.

Because we weren’t recording log, we had to do as much color-matching as possible in-camera. To accomplish this, we brought all of our camera’s profiles to neutral and worked our way up from there. We were using Panasonic’s AG-DVX200 as our main camera, with profiles generously provided by our account manager Steve Slade and Panasonic guru Barry Green, along with Sony’s a7S II, which was recording to an Atomos Shogun Flame; DJI’s Phantom 4, Osmo X3 and Osmo X5; and GoPro Hero4s and Hero5s. All cameras recorded in UHD to SD media, save for the Shogun, which carries its own SSDs. Capturing accurate skin tones with the Phantom 4s was not a priority, so we elected to let the Phantoms go with only a few minor adjustments, dropping the contrast and sharpness; we took a similar approach with the GoPros.

We inevitably encounter many wild color environments over the course of a season, so while we’re in production we do what we can to adjust on the fly. We’re not allowed to modify the lighting aboard the ships ahead of shooting, and we’re hard-pressed to find any two practical fixtures that match. Most of the shipboard lighting is fluorescent, and the ambient daylight temperature in Antarctica is a touch cooler than 5,600K. In Season 10, the organization gained a new ship, the Ocean Warrior, whose windows contained embedded heating elements that created an unpleasant color cast — something we could do little to control, and could only barely adjust for in-camera.

Shooting in Antarctica also brings with it high-contrast lighting environments, extreme temperatures, high winds, moisture and splashing, drone-calibration errors due to the ship’s constant movement, and compass errors due to the ship’s metal structure and occasional proximity to the South Magnetic Pole. Challenges aside, one of the great aspects of filming in Antarctica during the austral summer is the extended twilight hours; the sun never quite sets, and instead hangs around the horizon for three to four hours twice a day. It’s an absolute delight for a cinematographer.

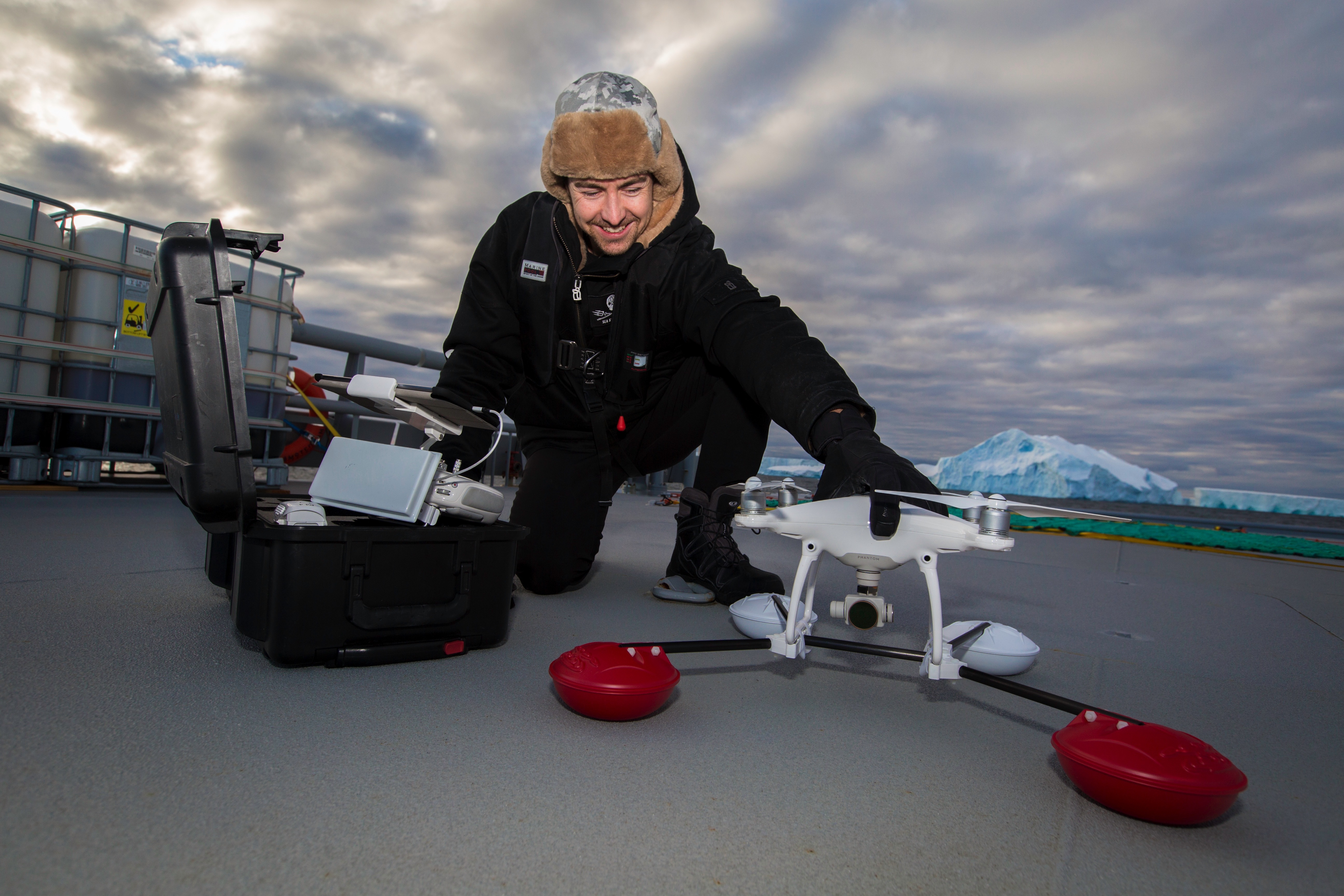

Knowing that we would need to be ready to fly at a moment’s notice, we built our drone kits to accommodate rapid deployment. For us, that meant using the CasePro Phantom 4 carry-on hard cases with custom foam, which allowed us to store the drones with the props installed and most of the accessories nestled alongside. Those accessories included PolarPro ND/PL filters, which I consider an absolute necessity; a long-range antenna-modification kit that helps ensure signal robustness when multiple drones are in the air at once; a desiccant pack; a lanyard for the transmitter; extra batteries; touchscreen gloves; an iPad; and Light & Motion’s Seca 2200D, a small LED light that can be rigged on the top of the drone via a GoPro mount and is excellent for peering into caves and other dark areas. With this arrangement, an operator could grab a single case and be ready to fly. On occasion, we also employed the Shogun as a director’s monitor, plugging in via the Phantom transmitter’s HDMI-out. Because we often fly the drones from rigid inflatable boats (RIBs), which are very wet and offer little room to maneuver while on board, having a well-packed kit is particularly critical to each flight’s success.

To provide some additional security while flying, we also carried a pontoon assembly from DroneRafts called a WaterStrider, which allows you to land on the water in an emergency. Many pilots who fly over water suggest attaching a hydrostatic float (originally designed for fishing poles), but we have avoided these due to their low success rate.

Once the drone is in the air, the trick is to capture shots that are a pleasure to watch, aid our narrative, and conform to the stipulations of our UAV permit, which is granted by the Australian Antarctic Division. It was quickly apparent that surprising the viewer wasn’t going to be difficult; with its icebergs, penguins, whales, seals and more, Antarctica abounds with fascinating frames. What we needed to do, we decided, was to go beyond the subjects alone and move our aerial cameras in ways that would help tell our story. Once we had a few flights under our belt, we began to grasp exactly how we could use aerial camera moves to aid our narrative.

For one thing, drones allowed us to get much closer to wildlife than we would otherwise have been able to, resulting in footage that many non-production crew remarked they “could see being on TV.” Drones also allowed us to provide context by situating the ships within the larger environment; you don’t quite grasp the scale until you see a ship dwarfed by the towering icebergs that dot the landscape. Even if we placed crew on an iceberg and sailed by a few times, we wouldn’t be able to achieve the sheer sense of scale we get from the air. In this case, the relatively wide angle of the Phantom 4’s lens plays to our advantage — the perceived distance between objects is slightly exaggerated, which underscores the expansiveness of the environment.

As with our “conventional” shipboard cinematography, we relied heavily on natural light to help improve the images we were capturing with the drones. We would position the Phantom 4 to place the sun behind icebergs and ships to create silhouettes, take advantage of twilight’s long shadows to create texture, and use the twilight hours’ lower ambient exposure to aid the small sensor’s compressed dynamic range.

We also employed classic camera moves to strategically reveal objects or place focus on an area. For example, we might skim the drone low over the water with the camera pointing 70 or 80 degrees down, then gain altitude and tilt up as the aircraft traveled up and over an iceberg, revealing a sunset or a ship in the distance; or we might move the drone laterally — as if it were on dolly track — from behind an iceberg, revealing a ship traveling on the other side. By taking advantage of planned camera moves, the environment, and the time of day, we were able to create the kind of cinematic shots that I wanted to replicate from Planet Earth II — and from Disney’s Soarin’ Over California, which I think stands as one of the finest examples of aerial cinematography.

Now that LED lighting has become so lightweight and powerful, we’ve started to attach fixtures such as Light & Motion’s 2200D to our Phantoms to help illuminate objects during both the day and night. The 2200D is powerful enough to create some additional fill in a cave or on the shadow-side of an iceberg. At night, a drone carrying a light can also create the feeling of a mystery — for example, when it illuminates the name on the side of a ship that’s a target of interest. Larger drones can carry lights like Light & Motion’s Stella Pro 10000C, which can more easily illuminate a large area. As both drone and LED technology continue to evolve, remote lighting is certain to play an increasing role in our productions.

For all that drones help us achieve, we can’t yet reconcile the disparity between the serenity of their gimbal-stabilized “God’s eye view” and the relative chaos of the handheld camerawork on the ship. The two perspectives feel very different. To me, though, this can create a welcome release; the drone footage allows the audience a moment to take a breath and soak in the scene before diving back into the handheld, high-energy footage and the adrenaline-pumping narrative.

Drones have certainly become an indispensable tool that adds enormous value to our productions. With them, we can achieve breathtaking imagery that just isn’t possible any other way — even with a full-scale helicopter. UAVs such as DJI’s Phantom 4 will continue to inform how we go about shaping the aesthetic of our shows. As long as we strategically deploy these highly capable tools to underscore our storytelling, I have high hopes that drones will help us craft narratives that continue to surprise and delight audiences around the world.