It’s Time for a Broad Conversation by the Entire Filmmaking Community

In Halyna’s memory, we need to do better on set.

Words failed me in the moment following the death of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins on October 21, 2021. But words are all we have, and in the days following Halyna’s death, I have heard — and said — words expressing shock, anger, sadness, disbelief and frustration.

Shock, because cinematographers are not killed in the line of duty. Of course, many have been, but it is still a traumatizing shock.

Anger, because cinematographers are not killed in the line of duty. It is infuriating because we have all worked without incident with weapons. For a cinematographer to die this way is completely, totally wrong.

Sadness, because cinematographers should not predecease their parents and leave children motherless.

Disbelief and frustration, because all cinematographers working for major employers must pass safety exams that educate them about any and all hazards encountered in filmmaking and how to avoid them.

On November 14, we announced that the ASC Board of Governors had decided to confer honorary ASC membership on Halyna Hutchins. It is some small consolation for us to know her name will be on the roster of ASC members for as long as the Society continues to exist. As we honor her memory, however, we must also honor our responsibility to everyone we work with on set by speaking up about the very serious issues relating to safety.

The hazards are no secret: physical stunts of all kinds that often go in directions unplanned, vehicle driving stunts, rollovers, crashes, jumps that involve enormous kinetic energy and can become very dangerous before the shout of “look out” can be uttered or heard. The hazards are legion, but harm befalling a crewperson is seldom so catastrophic as what happened on the set of Rust on October 21. Of all the hazards associated with filmmaking, the far less dramatic issue of fatigue is routine and the most common — and yet it can be just as deadly. While hazards are the subject of an intense series of lectures given by Contract Services (an arm of the studios to satisfy OSHA that the work force of the 13 Western States is trained to be safe), little is said about working tired. In fact, Local 600 — representing camera crews of the IATSE union — has a safety app you can download which can be used to alert 600 to hazardous conditions. Whether or not you work in the 13 Western States, you can read the app, which contains all the safety bulletins union camera crews are familiar with.

We are certain that in the current post-pandemic “take this job and shove it” atmosphere, a casual attitude about long days will not be tolerated. There is ample evidence that a 12-hour workday, plus two hours commuting, equals an impaired driver on the way home. It also means someone who’s impaired handling lenses or C-stands on set — or even more dangerously, someone driving a motor vehicle on camera that can become a lethal weapon when their judgment is impaired by fatigue.

All of this means it is time for a broad conversation by the entire filmmaking community across the U.S.A. about the addiction we have to long hours for production (and postproduction). Every filmmaker has a reason why long days are necessary. For some it is the need for a decent paycheck that comes with overtime pay and penalties. For some it may be actors’ schedules. For some in the production department it may be a bonus for coming in under budget. No matter one’s reasoning about the need for long hours, it is abundantly clear that working impaired can kill, one way or the other.

An industry-wide conversation should be frank and it should be open — everyone has a voice when it comes to safety. We probably have all experienced situations on set when something being proposed or carried out appeared unsafe, but crewmembers felt inhibited from speaking out because they feared for their next job, or because they felt nobody would listen.

In a special feature in our January issue, a series of filmmakers with different positions — and responsibilities — write about their perspectives on safety issues. That is a start. The American Society of Cinematographers will do more. We are using any format we have access to, whether at Camerimage or the Hollywood Post Alliance, to make the case that filmmakers should work normal hours so we all can have a normal family life. The ASC will use our Future Practices Committee — originally formed to talk about the challenges of working under Covid-19 — to bring filmmakers together. It is time to have this conversation about long hours and a range of other safety issues. We cannot be shocked, angry, sad or frustrated at another death during production.

In Halyna’s memory, we need to do better on set.

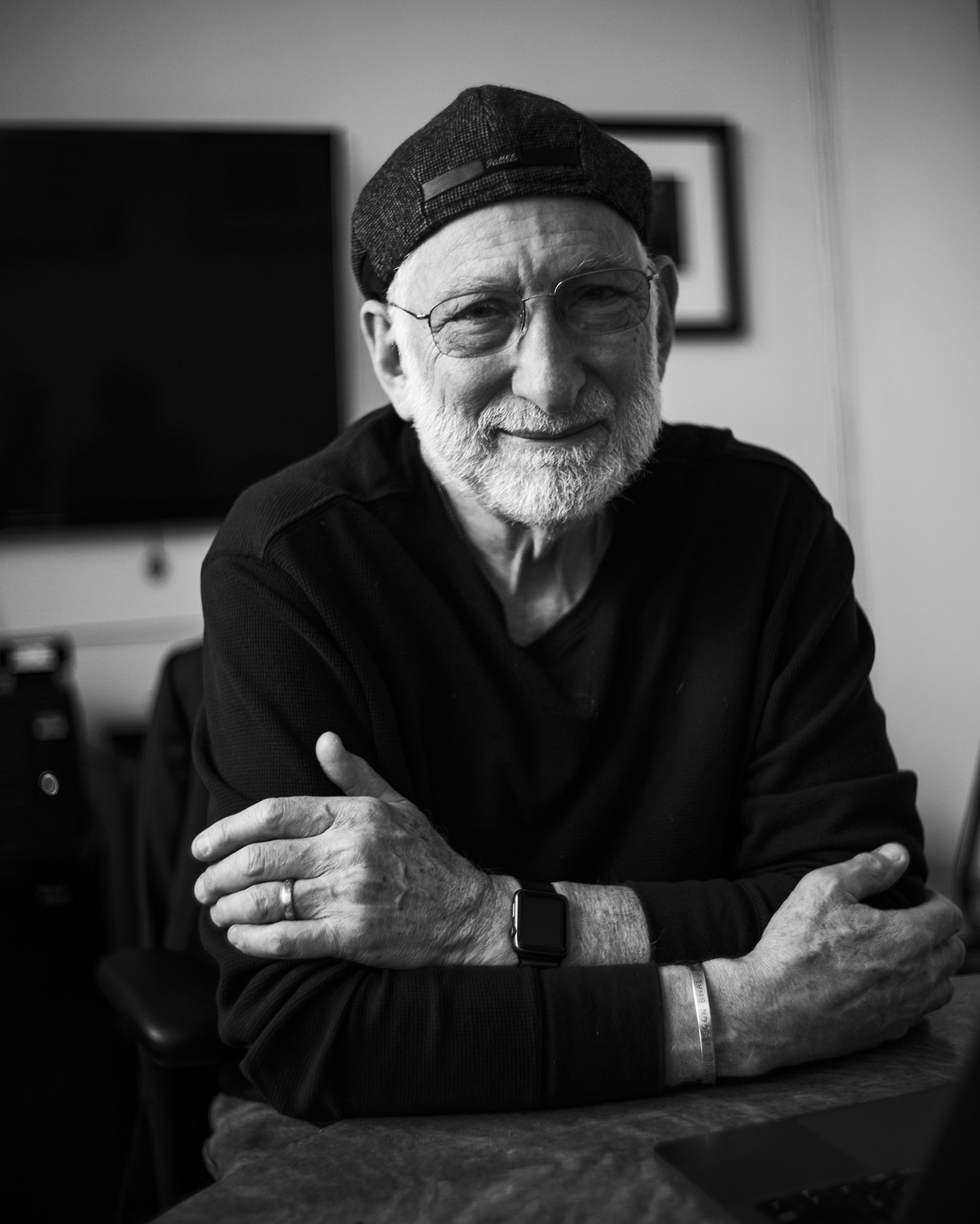

Stephen Lighthill

President, ASC