President’s Desk: The Nine Lives of the Cat!

“What baffles me to this day is that other manufacturers have seemed to adopt the idea of a well-balanced camera only reluctantly and never completely.”

We’ve all heard the saying: “Cats have nine lives.” It’s a popular myth, one that’s been around for hundreds of years — and one that even earned a reference from no less a legend than Shakespeare, who worked it into Romeo and Juliet, giving Mercutio the line, “Good King of Cats, nothing but one of your nine lives, that I mean to make bold withal, and, as you shall use me hereafter, dry-beat the rest of the eight.”

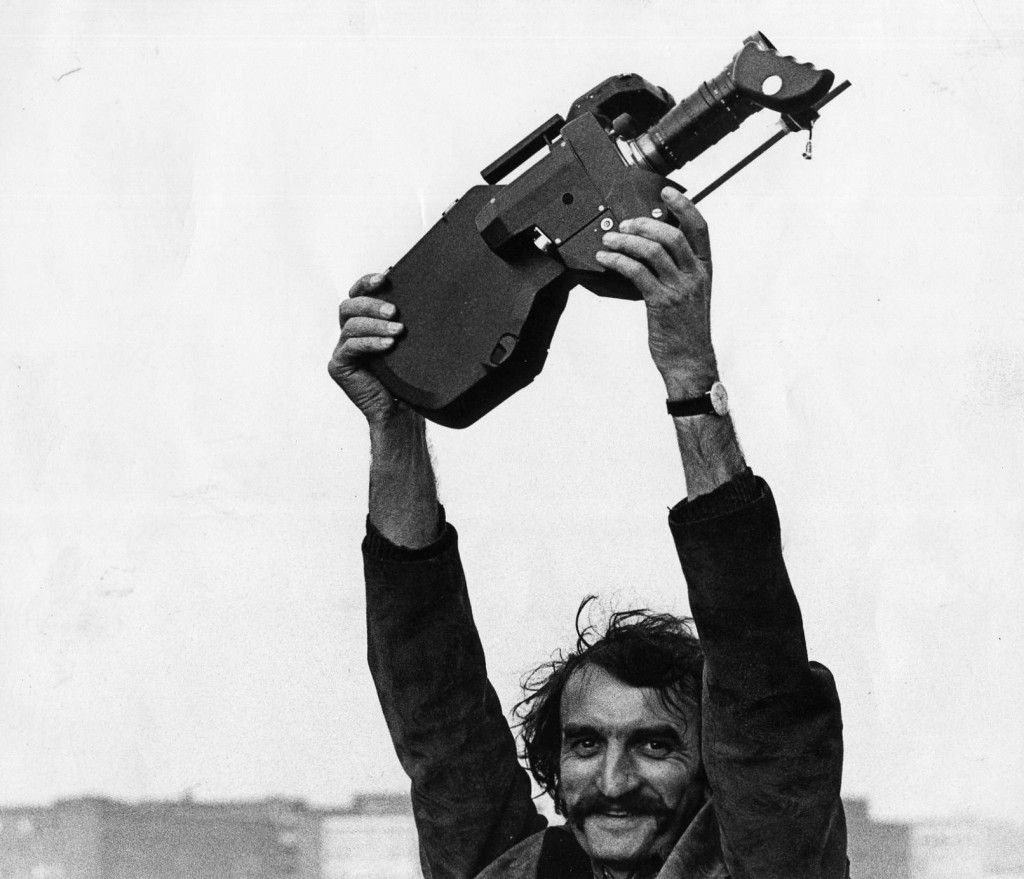

Where the cat’s cultural significance becomes relevant for this column is in the marketing campaign that accompanied the debut of Jean-Pierre Beauviala’s first Aaton 16mm camera, which he likened to a cat on the operator’s shoulder. This came at a time when shoulder designs for film cameras were nonexistent.

At the beginning of the motion-picture industry, the Lumière brothers designed their “cinematograph” as a wooden box, square and plain. For decennia to come, the principle of designing a “box” remained largely in effect. The Arriflex departed from the conceit, as did Éclair’s NPR, designed by André Coutant. Nevertheless, those cameras weren’t exactly balanced, and a good amount of muscle was necessary to keep them steady. So, when Beauviala introduced his new camera — one that can straddle the operator’s shoulder in a way that it can almost be left to sit there without support — he effectively launched the concepts of balance and ergonomics as they apply to camera design.

Beauviala founded Aaton in Grenoble, France, after having worked as an engineer at Éclair. Under Beauviala’s leadership, Aaton introduced its first 16mm camera in 1971 and went on to develop an array of small and reliable motion-picture film cameras, all of which were produced according to the “cat on the shoulder” ethos. Aaton’s LTR 16mm camera was succeeded by several models, including the LTR 54, XTR, X0, XTR Plus, XTR Prod and A-Minima, the latter of which is a small, specialized Super 16 reflex camera that takes 200' loads. Aaton has also made very successful 35mm cameras, including the Penelope, which is field-switchable between 2-perf and 3-perf.

Lastly, the company developed the digital Delta camera. Evolving from an early design that swapped the Penelope’s film magazine for a digital recorder, the Delta featured one of the first ground-glass optical viewfinders for a digital camera, along with a rotating mirror shutter to avoid rolling-shutter artifacts. The camera worked with an internal SSD recorder for full-resolution CinemaDNG uncompressed raw as well as editorial-ready proxies. And, true to Beauviala’s original vision, the Delta was lightweight and maintained the company’s cat-on-the-shoulder profile.

What baffles me to this day is that other manufacturers have seemed to adopt the idea of a well-balanced camera only reluctantly and never completely. Yes, Arri made vast improvements with the SR through to the 416 camera. And at certain times Beaulieu and Bolex followed. But nobody bent the rules — or the camera, for that matter — as consistently as Aaton. And now, in this era of digital cinema cameras, we seem to have gone completely retro. Let’s face it, like the Lumières’ wooden box, digital cameras are square, unbalanced, incomplete structures. And in lieu of ergonomics, they’ve given rise to a thriving cottage industry of shoulder pads, flex mounts, bean bags and other contraptions.

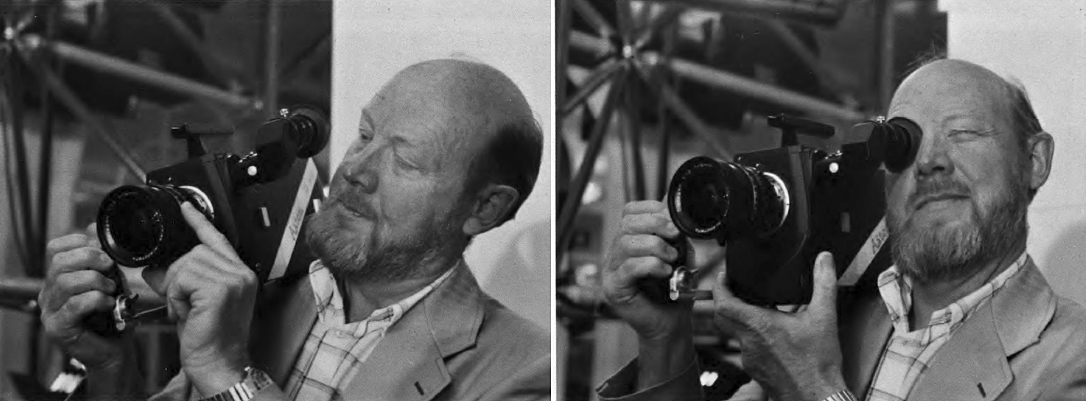

Jean-Pierre Beauviala has always thought outside the “box.”

In November, in recognition of his groundbreaking work and lasting contributions to our industry, the ASC presented Beauviala with a special award. As the ancient proverb says, “A cat has nine lives. For three he plays, for three he strays, and for the last three he stays.”

Kees van Oostrum

ASC President