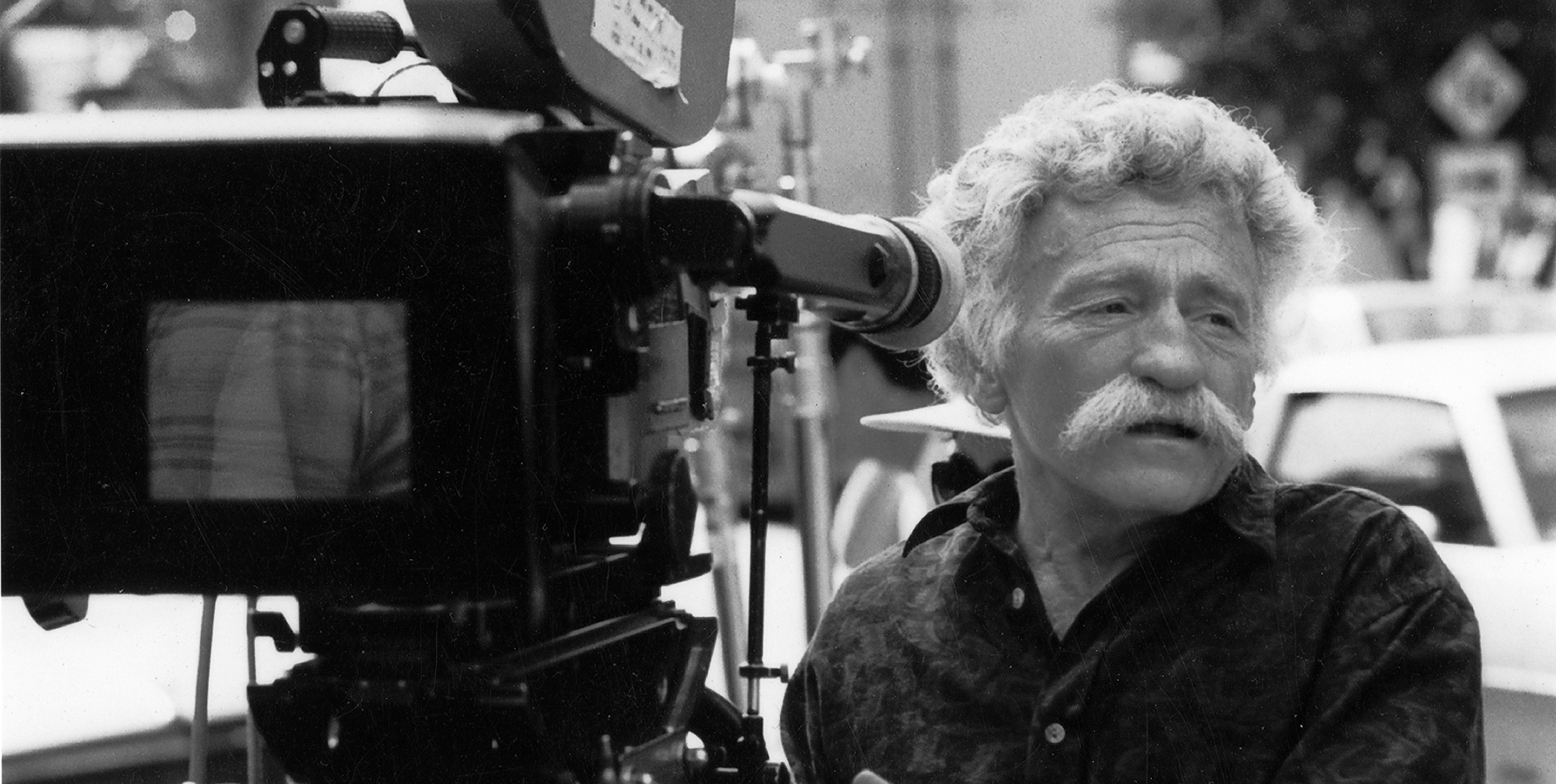

In Memoriam: Isidore Mankofsky, ASC (1931-2021)

An award-winning cinematographer and very active member of the ASC, his credits include The Muppet Movie, Somewhere in Time and The Jazz Singer. He passed on March 11 at the age of 89.

Born in New York City on September 22, 1931, Isidore “Izzy” Mankofsky, ASC’s career path was not a direct one. Raised in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Chicago, he didn’t sit in a darkened theater as a child and see a classic film that wowed him. His parents weren’t artists; they emigrated to the U.S. from Odessa, Ukraine, in 1923. He didn’t take any art classes, and he never went to the ballet or opera. He didn’t even own a camera, but when the time came for a career decision, he plucked “photographer” seemingly out of thin air. “When I was in high school, somewhere along the line, it dawned on me that I’d like to do photography,’ he told American Cinematographer on 2009 when he was honored with the Society’s Presidents Award for his decades of leadership and service to the organization. “I don’t know where that came from.”

Mankofsky got his first camera after graduating high school, just before he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, which took him to Germany and then Korea. He recalled, “It was a 35mm Argus C3, and I’m not sure how it came into my hands, but it wasn’t with me for long — after it got plenty of use in basic training, I lost it in a poker game to a quartet of noncoms.”

While stationed in Germany, he was assigned to the motor pool. After relentlessly badgering the squadron commander, he received a transfer to special services, where one of his jobs was to take pictures of the base athletic teams for the base magazine. Knowing nothing about photography, he had to learn to shoot, process the film and print the pictures. “You could say that was the beginning of my career in the magical world of motion pictures,” he noted wryly.

Following his honorable discharge, Mankofsky enrolled in the Ray Vogue School of Photography in Chicago, but a quick look around revealed a lot of competition: “Then, as now, everyone who picked up a camera thought he was a professional photographer. But motion-picture photography was different — it was magical. It hadn’t dawned on me that it was just 24 still frames per second.” Mankofsky traveled to Santa Barbara, Calif., to enroll in the Brooks Institute of Photography’s motion-picture track.

When one of his instructors got a call for an “all-around” person to work at KOLO television station in Reno, Nev., Mankofsky interviewed for the job and was hired. One of his first assignments was to document, on black-and-white 16mm, the new TV-antenna building on Mount Rose. “I still have the film, my first effort as a professional cinematographer,” he noted. He returned to Chicago and worked as an industrial photographer at Stewart Warner Electronics for a short time, and then, just when he was about to return to California, a stroke of luck occurred during a handball match at the local YMCA. His opponent, Jim McGuinn, a producer of educational films at Encyclopedia Britannica Films, asked if Mankofsky would be interested in shooting a series in Florida. Over the next 13 months, Mankofsky shot 161 half-hour 16mm films — an education unto itself.

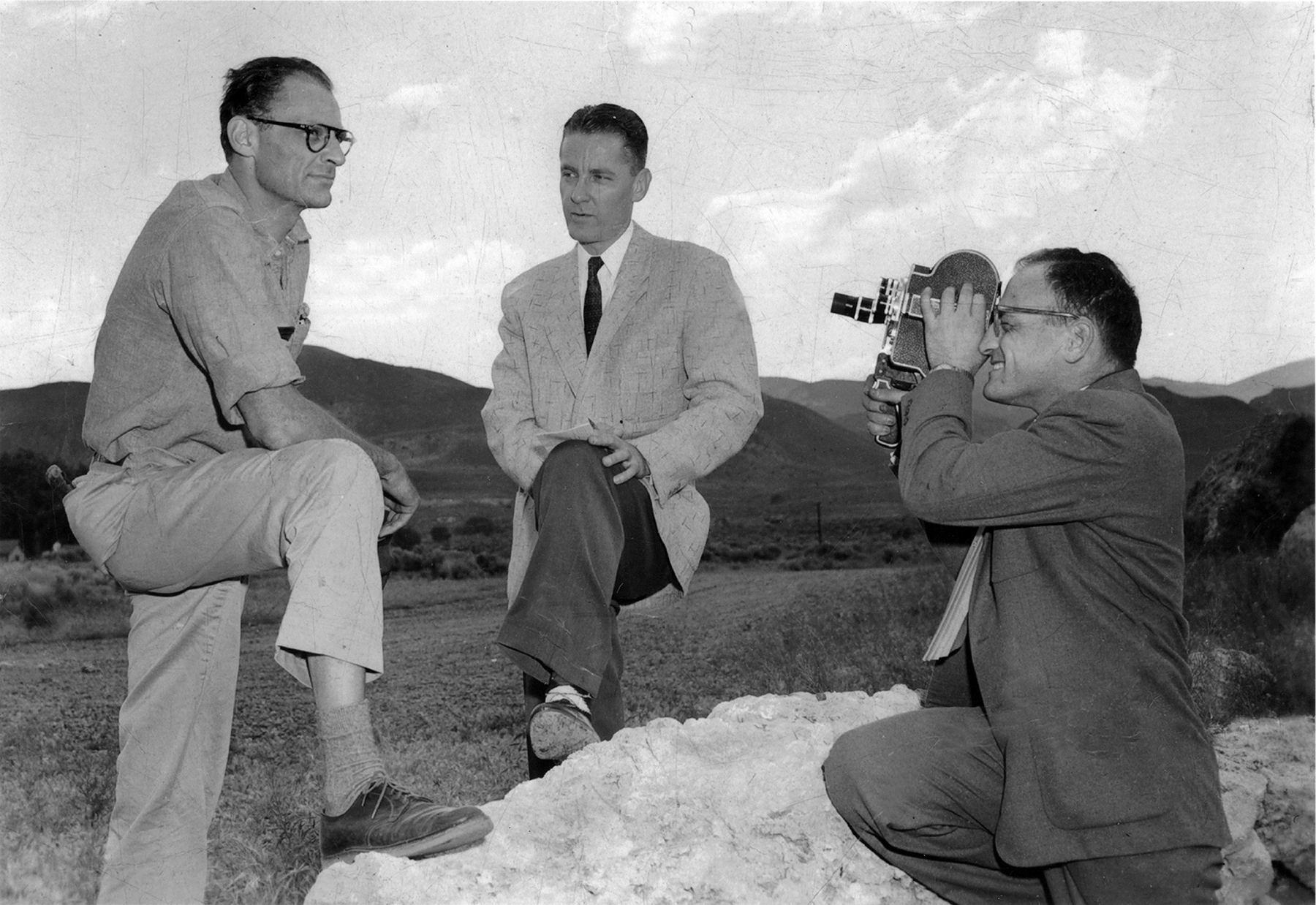

One of his frequent collaborators at Encyclopedia Britannica was director/ producer Larry Yust. Their 1969 film version of Shirley Jackson’s disturbing short story The Lottery, part of Encyclopedia Britannica’s Short Story Showcase series, gave Mankofsky the opportunity to try shooting a narrative project:

Frequently screened in schools as a teaching tool in literature classes, the short would become one of the most popular Encyclopedia Britannica titles of all time.

And Mankofsky’s work at Encyclopedia Britannica was a training ground, much like music videos and commercials are to today’s cinematographers. “Each film was an opportunity to do something that I added to my book of knowledge;’ he explained. “Because each film presented its own problems, the cinematographer was, among a lot of other things, a problem solver. I learned as I went along. Of course, I made mistakes. I did everything — aerials, time-lapse, high-speed. I can’t even swim, and I shot water work! In my nine years at Britannica, I don’t think I had to reshoot anything. I’m sometimes asked how I learned composition, and it just came to me.” He added that Yust was such a stickler for symmetry that “he has influenced my framing ever since!”

Mankofsky spent 17 years trying to join the camera guild, to no avail. When a group of cinematographers filed a lawsuit that ultimately broke down the union’s wall of nepotism, Mankofsky, though he wasn’t part of the suit, was grandfathered in.

This professional breakthrough led to shooting his first union project, American International Pictures’ horror sequel Scream Blacula Scream (1973). On that picture, the dilemma was shooting a dark-skinned actor, the imposing William H. Marshall, who was wearing a mostly black costume at night in his lead role.

“In my days at Britannica, I shot with Kodachrome, which was a very contrasty film,” Mankofsky recalled. “I had learned to be very careful with my lighting because Kodachrome didn’t have much latitude, maybe one stop, and then you were in trouble. Print stocks at the time weren’t very good; they were also contrasty. I had to get the contrast down, and I did that by having the lab flash the film.” Flashing the film, which brings up detail in the shadows but does not affect highlights, would have some producers breaking into cold sweats, but the powers-that-be had no idea Mankofsky had instructed the lab to do such a process. In that era, he notes, producers were more handsoff. “They weren’t quite as dictatorial as they are now,” he joked. The lab technique proved to be a success.

In 1975, Mankofsky started working at Universal TV. His agent had received a call from a production that was seeking a feature cameraman to shoot a pilot, and from then on, Mankofsky was quickly pigeonholed as a TV cinematographer, a tag he felt he never completely shook. “I felt like it held me back,” he said. “But I stuck to my guns in not shooting series.” He instead specialized in miniseries and telefilms; his credits including Captains and Kings (1976), Columbo: How to Dial a Murder (1978), Goldie and the Boxer (1979) and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy (1981).

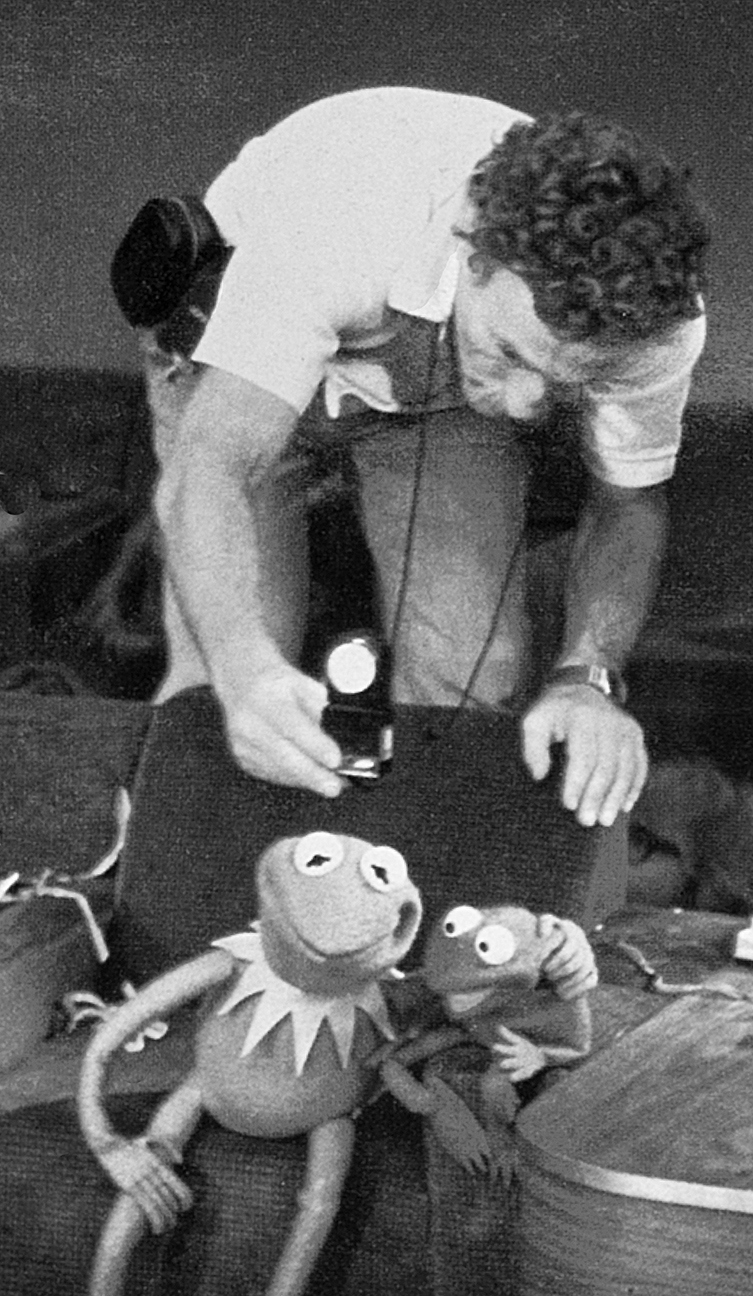

During this stretch, Mankofsky also shot some features. In 1979, producer Jim Henson called upon the cinematographer to shoot The Muppet Movie, the popular television characters’ first big-screen adventure, directed by James Frawley. Henson’s hit The Muppet Show was shot in broadcast video and had a high-key, live-TV look that everyone knew wouldn’t translate to the big screen, and Mankofsky had to devise more cinema-appropriate visuals. The only caveat Henson had was that the Muppets’ distinctive colors — especially Kermit the Frog’s signature lime hue — had to remain true. “Green on film, especially at night, can be tough, and Kodak stocks at the time weren’t particularly sensitive to green,” noted Mankofsky. “But it was great working with the Muppets. First of all, no one complained about the light in his eyes or how long he had to stand in — you just stuck them on a pole. And the puppeteers were really nice guys. When I asked Henson to move Kermit to the right a little for a better frame, Henson [who personally operated and voiced the character] wouldn’t answer — Kermit would answer.

“Henson didn’t want any visual effects,” Mankofsky continued. “He wanted everything live [in front of the camera]. For example, when Kermit was driving an old Studebaker, four or five puppeteers were working the puppets from the floor of the car, so the car had to be modified so it could be driven from the trunk. The wide-angle lens of a video camera poked out of the car’s distinctive grill so the driver could see.

“The question I’m asked most about The Muppet Movie is how Kermit rode the bike. We took a crane with an arm extended out, and monofilament ran from that down to the bike. Kermit’s feet were strapped to the pedals, and the pedals would turn as the bike wheels turned. The voice and mouth movements were remote-controlled; we’d just pull it along:

“However, the shot I’m most proud of is the one that shows Kermit sitting in a director’s chair on a big soundstage. Where’s Henson? I did that in such a simple way, and no one has figured it out. I put a couple mirrors in [below the chair], and Henson is behind the mirrors. I lit it so the shadows in the mirrors looked like they continued past the chair legs.”

Mankofsky followed The Muppets with the romantic period drama Somewhere in Time (1980), starring Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour. He had met the director, Jeannot Szwarc, while at Universal. ‘‘I’d subbed on a couple of shows Jeannot was doing,” he remembered. “One Sunday morning, he called me up to see about having breakfast at Canter’s, and he asked if I’d do the film. We had a great relationship on the film, but oddly enough, I never worked with him again, nor with any of the executives on that film. They never called me back, and I’ve never known why!”

Mankofsky marveled at Seymour’s photogenic quality: “No matter how you lit her, she looked gorgeous. The light just wrapped around her. Of all the actresses I’ve photographed, she was the easiest.”

Somewhere in Time didn’t do particularly well in its theatrical release, but it eventually gained a fervent cult following. Avid fans of the film still hold an annual convention at the shoot’s location, Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Mich. — which Mankofsky attended many times as a celebrated guest.

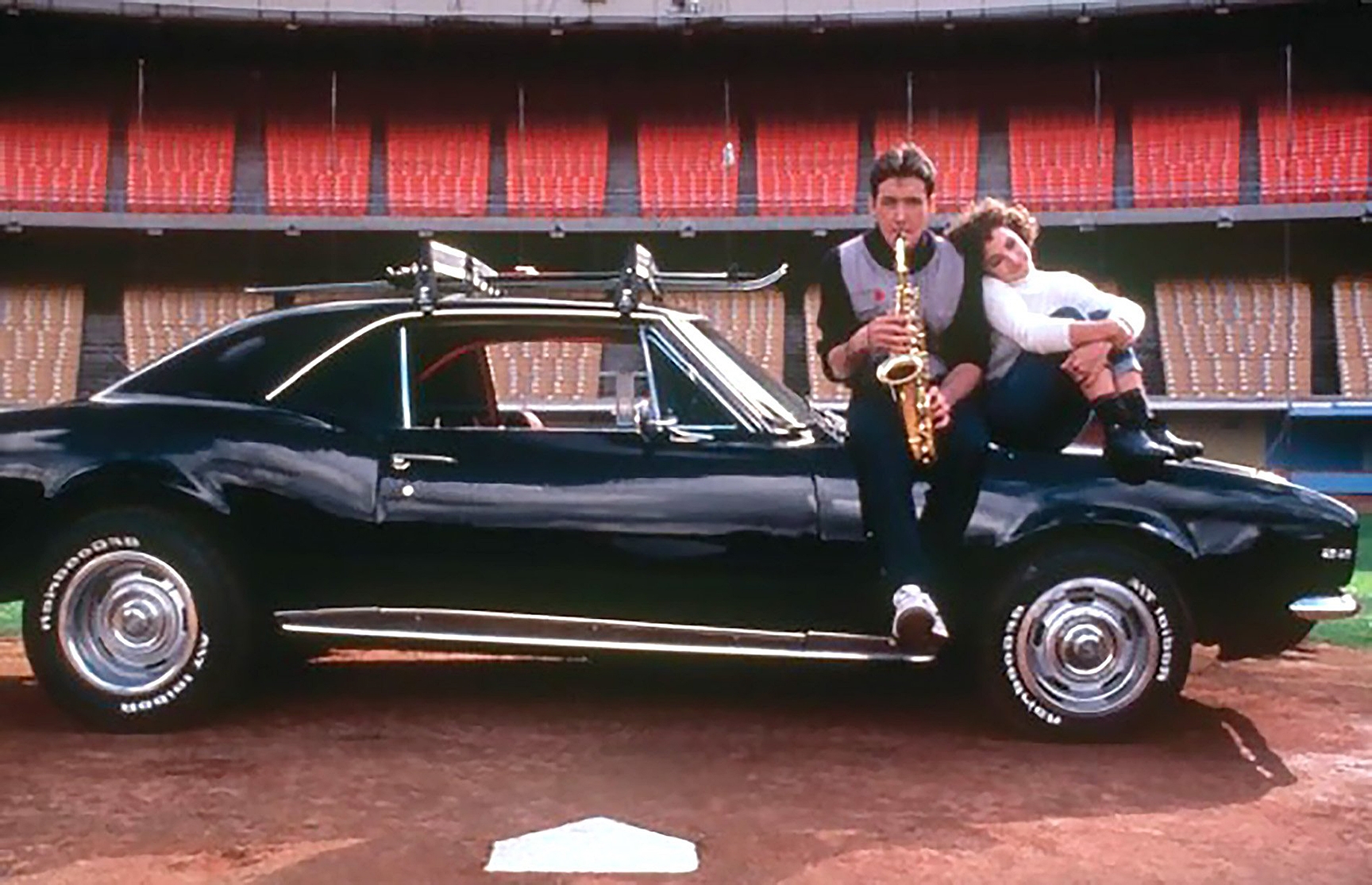

Mankofsky soon shot another feature, Richard Fleischer’s The Jazz Singer (1980), and then photographed several telefilms, including Portrait of a Showgirl (1982), In the Custody of Strangers (1982) and The Burning Bed (1984). In 1985, he hooked up with imaginative director Savage Steve Holland to shoot the absurdist teen comedy Better Off Dead, starring John Cusack.

The film was a surprise hit, and Warner Bros. ordered up another Holland/Cusack picture, One Crazy Summer. Mankofsky recalls, however, that Cusack refused to do some of the gags in the second picture. “A lot of the material [in the script] that was really good isn’t in the movie,” said the cinematographer. “Or, if it’s in the film, it isn’t the way it was supposed to have been done.” On both projects, Holland managed to lure Mankofsky in front of the camera for a cameo. “In One Crazy Summer, he had me brushing the teeth of a fake dolphin, and he also had me inside the thing to film in the water,” he remembered. “In Better Off Dead, I’m the neighbor wearing an aardvark coat, cutting the hedges.”

Sandwiched between those comedies was a George Lucas TV spectacle, Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (1985), a sequel to The Ewok Adventure. On The Ewok Adventure, producer Thomas G. Smith had called Mankofsky to shoot the second unit for Industrial Light & Magic; the two had worked together at Britannica. “Tom is one of the most loyal people I’ve worked for,” Mankofsky noted. “Whenever he had the opportunity, he’d try to get me on a film.”

When John Korty, director of Ewok Adventure, had to leave the production early due to a scheduling conflict, “George Lucas decided to direct the rest of it, and I shot that material,” Mankofsky said. “George is a very, very nice man but an impatient director. He’s a lot like me; when something starts to slow down, I’ll go and do it myself.”

When time came for the Ewoks sequel, Mankofsky shot first unit for directors Jim and Ken Wheat. Actor Wilford Brimley didn’t get along with the directing duo, so scenes featuring Brimley were directed by production designer — and future director — Joe Johnston. “I would quietly go over to Wilford and ask him to move his hat a bit so I could see his eyes, and he’d say, ‘Oh, sure,’” recalled Mankofsky. “If the Wheats had asked him that, he would have thrown them off the set.”

Over the next 10 years, Mankofsky shot numerous TV movies, including Fatal Judgment (1988), A Very Brady Christmas ( 1988) and The Heidi Chronicles (1995). He earned Emmy nominations for Polly (1989); Love, Lies and Murder (1991); and Afterburn (1992). He won an ASC Award for Love, Lies and Murder and notched additional nominations from the Society for Davy Crockett: Rainbow in the Thunder (1989) and Trade Winds (1994).

In 1991, Mankofsky reunited with the Muppets to shoot a special-venue film in 3-D, a new format for him. On MuppetVision 3-D, which played the Disney Hollywood Studios park for almost two decades, Mankofsky was the creative cinematographer while Peter Anderson, ASC served as the technical cinematographer. “Peter wanted to shoot tests every day, but the producer came in and said, ‘Just shoot, and if it doesn’t turn out, then that can be considered the test,” Mankofsky remembered. “We only had to reshoot one day out of the whole schedule, and that was because the [interlocked] cameras went out of sync.”

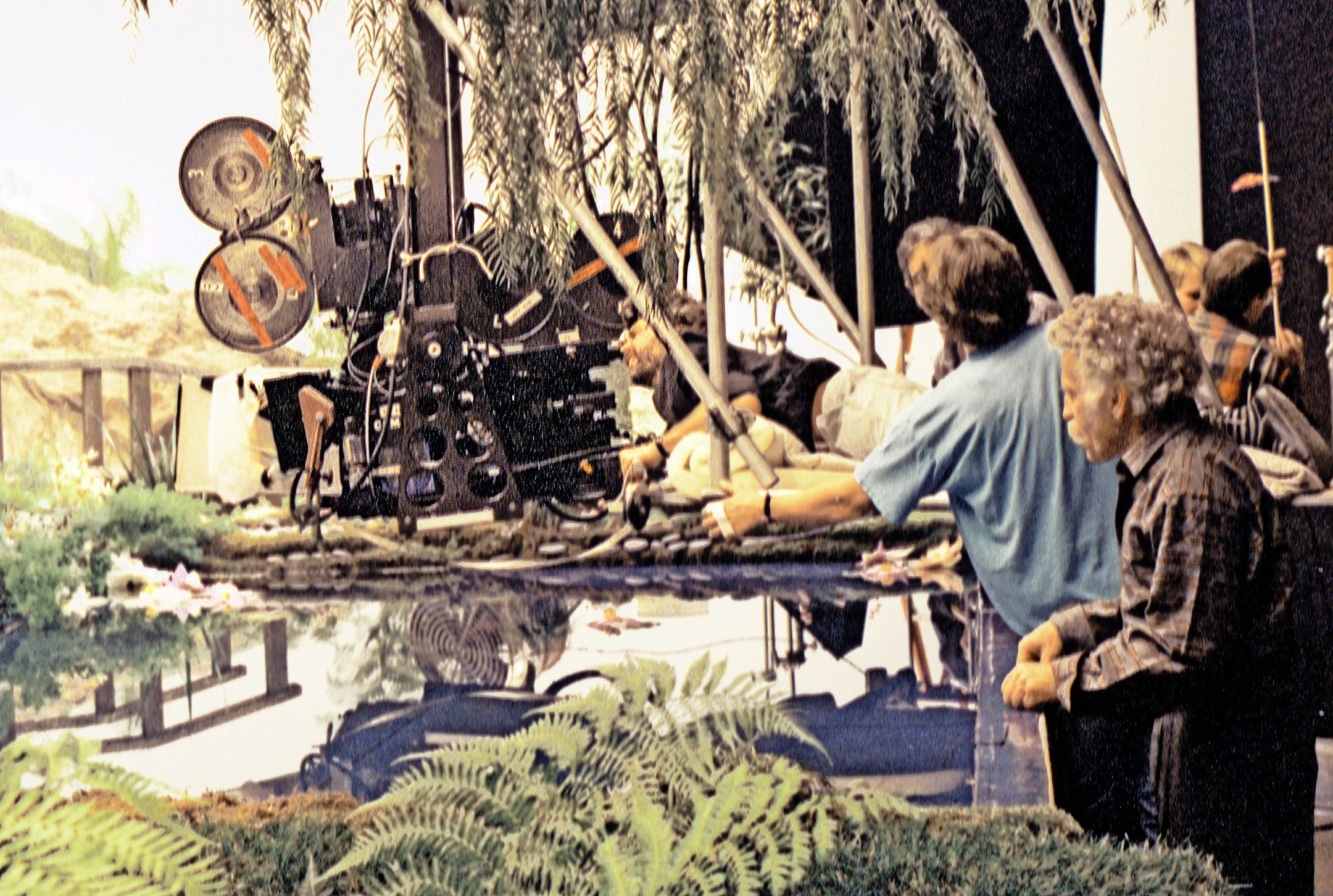

Mankofsky remembered the massive amount of light needed for the shoot: “On a big outdoor set where Miss Piggy is fishing, I had 100 coops that each held six 1,000-watt bulbs just to get the fill-light level where we wanted it. For a key light, I had an 18K, and for back light, I had a Xenon. It got so hot up in the permanents that we had to stop shooting; it overpowered the air-conditioner! I needed 1,600 footcandles and had no idea how to get that, but after turning on all those coops, I put my meter up, and it read 1,600 footcandles exactly. Whew!”

When Mankofsky started down his cinematography path, he had two goals: to win an Academy Award and to join the ASC. The goal he has met has turned out to be the most rewarding, he says.

Recommended by Society members Howard Schwartz and Harry Wolf, Mankofsky joined the ASC in 1979. He subsequently served for many years on Society’s Board of Governors — including positions as secretary and sergeant-at-arms — and chaired many committees, including ASC Student Heritage Award Committee, the Constitution and Bylaws Committee and the Newsletter Committee.

He also served as the curator of an exhibit of ASC members’ still photography. “I don’t know why I do all those things!” he told AC with a laugh. “When I was in the service, they told me to never volunteer for anything. But I’ve never been one to just sit around the house.”

Mankofsky is survived by his wife, Christine — the two married in 1972.