In Memoriam: Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK (1935-2017)

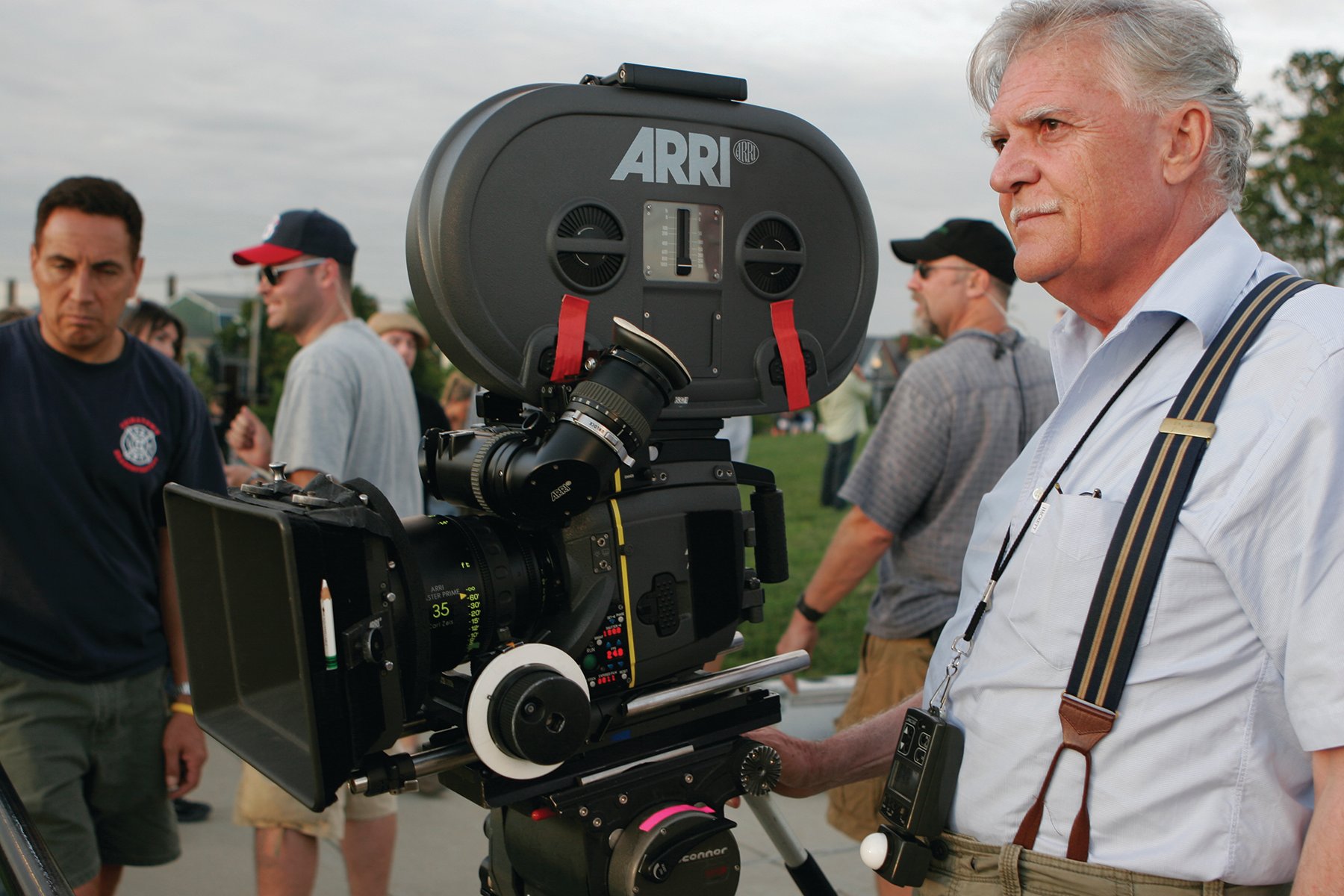

One of the most esteemed and influential cinematographers of the modern era, Ballhaus, died at his home in Berlin on April 12 at the age of 81.

“One of our great cinematographers passed — one of the ultimate ambassadors of our artistry and technology,” says ASC President Kees van Oostrum. “His keen vision will be missed by all of us, but he leaves us with a tremendous and inspiring body of work. Our thoughts go out to his immediate family, including his son Florian Ballhaus, ASC.”

All cinematographers have their own philosophies about the art form. Some advocate tableau-like composition, while others prefer more kinetic displays of camera magic. Ballhaus unquestionably belonged to the latter camp, but he had a simple, sensible explanation for his roving eye: “If it’s a movie, it’s got to move.”

Throughout his career, Ballhaus partnered with directors who encouraged his camera to swoop, glide and soar with lyrical abandon. A native of Germany, he gained a great reputation with his early work for prolific wunderkind Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who pushed him to shoot fast and think on the fly. After immigrating to the United States in the early 1980s, Ballhaus began a close and enduring collaboration with Martin Scorsese, whose penchant for dynamic camerawork is legendary. He also shot films for John Sayles, James L. Brooks, Mike Nichols, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Redford, Wolfgang Petersen and Barry Sonnenfeld, among others.

Along the way, Ballhaus created a jaw-dropping body of work. His 15 films with Fassbinder would alone merit a career achievement award; particularly notable titles include Whity, Beware of a Holy Whore, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Martha, Fox and His Friends, Chinese Roulette, The Stationmaster’s Wife and The Marriage of Maria Braun. But his Stateside output is even more impressive. Ballhaus earned Academy Award nominations for Broadcast News, The Fabulous Baker Boys and Gangs of New York, and the latter picture also earned him an ASC Award nomination. His other U.S. credits include After Hours, The Color of Money, The Last Temptation of Christ, Working Girl, GoodFellas, Postcards from the Edge, Guilty by Suspicion, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, The Age of Innocence, Quiz Show, Air Force One, Primary Colors, Something’s Gotta Give and The Departed. Suffice to say, the man knew his way around a camera.

The American Society of Cinematographers formally applauded Ballhaus for his artistry by presenting him with the ASC International Award at the organization’s annual awards gala, held on Feb. 18, 2007 in Los Angeles. Although he had earned many accolades over the years, Ballhaus said the International Award was particularly special. “This award comes from the best cinematographers in the world, which means a lot to me. I’ve worked pretty hard over the years, but I’ve also been very lucky,” he told American Cinematographer editor Stephen Pizzello with characteristic modesty. “Making movies was a hobby that I turned into my job. If everyone knew how much I loved doing it, they wouldn’t give me any money!”

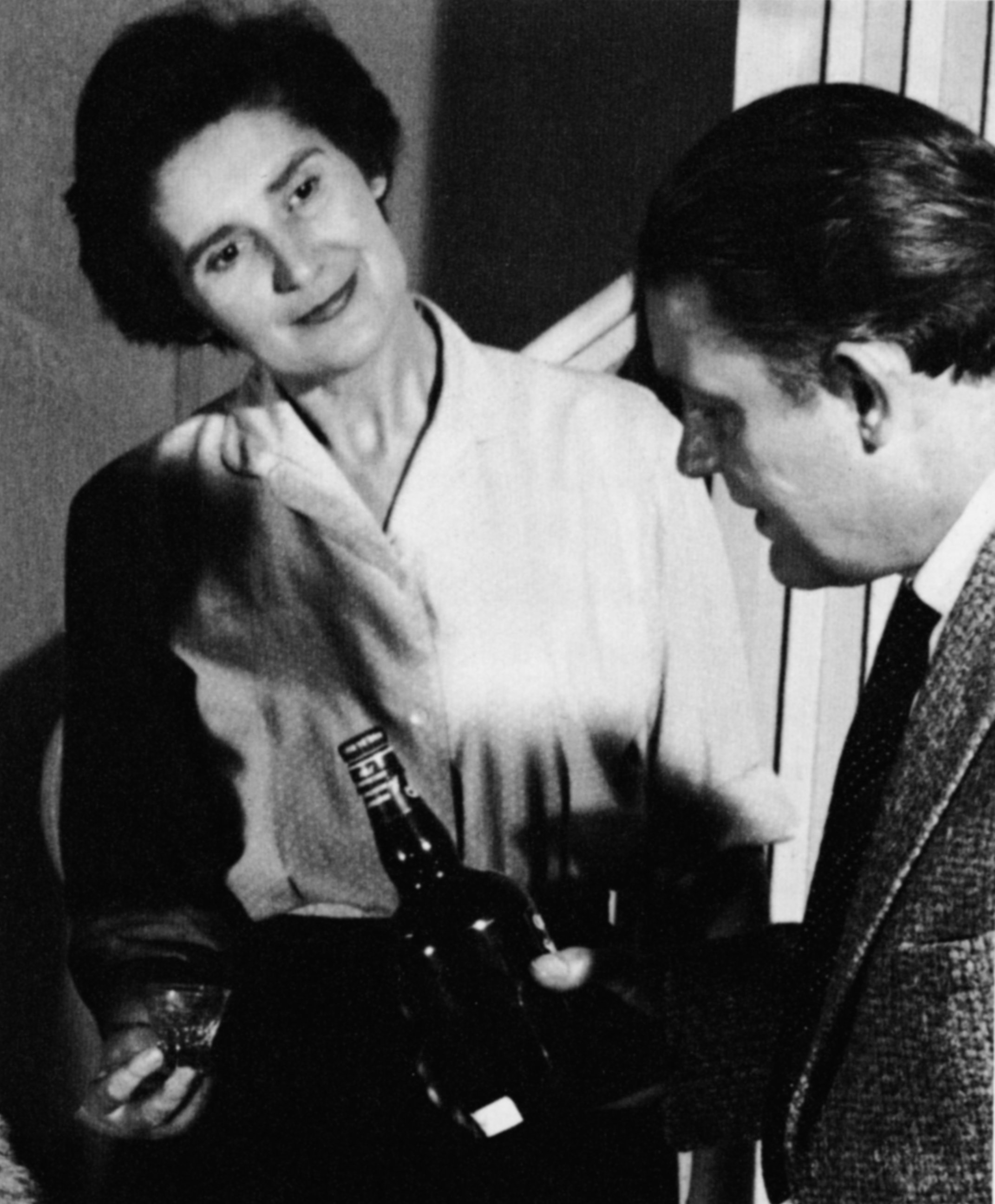

Ballhaus’ career in the arts was almost preordained. He was born in Berlin on August 5, 1935, to stage actors Oskar Ballhaus and Lena Hutter, who encouraged his creativity. He recalled that in 1943, “with bombs falling on Berlin every night,” the family took refuge in the quiet Bavarian town of Coburg. “My parents influenced me a lot,” Ballhaus said. “Right after the war, they founded a cultural agency and began inviting orchestras and conductors to come to Coburg to play works by the great German composers: Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms. Two years later, they founded the Fränkische Theater, which was headquartered in an old castle near Coburg. I was going to school, but in my free time I did everything I could to help out at the theater. It was a lot of fun.”

Ballhaus’ love of cinema took root in his teen years. After developing an interest in still photography, he had an opportunity to visit a family friend, renowned director Max Ophüls, on the set of Lola Montès. “I was there when they shot the big circus scenes, and it was amazing to see 300 extras and all of these cameras, cranes and lights. The director of photography was Christian Matras. He didn’t speak a word of German and the gaffer didn’t speak a word of French, but they could still communicate with each other, and it was great watching them work. They would hold up five fingers or 10 to indicate whether they would need a 5K or 10K. I was fascinated to know how all of the machinery worked with all of the tracking shots.” Indeed, Ballhaus felt that his up-close observation of Ophüls’ gliding camera may have influenced his own style. “When the movie came out, I saw it many times, and I just loved the way he moved the camera. I also loved what he did with color.”

After studying photography for two years and becoming “an officially certified 35mm photographer,” Ballhaus moved with his wife, Helga, to Baden-Baden, where she had landed a job at a nearby theater. “I started looking for a job, and I eventually got an offer to be an assistant on a documentary about Greece,” he recalled. “I kept telling the director to move the camera, but he was an old-fashioned guy, and I don’t think he appreciated my suggestions very much!”

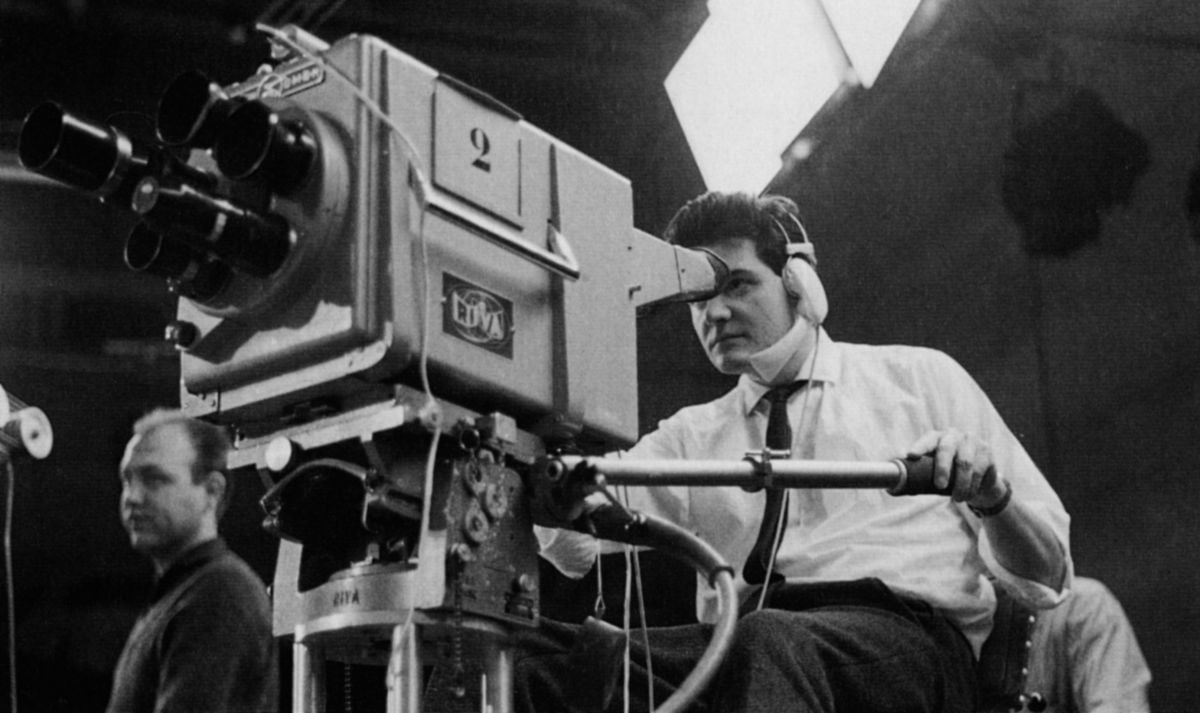

Ballhaus hoped to find work on feature films but initially had no luck. “Then this TV station opened up in Baden-Baden, and they needed operators for these big electronic cameras. I got a job, and I worked in TV for almost nine years in Baden-Baden and Munich.” After gaining experience shooting TV movies on film, he shot his first theatrical feature, Der Klassenaufsatz, when he was just 25. “I learned that making a movie involves teamwork. The director and I were well prepared. I was a good operator, thanks to my work with those big TV cameras, but I needed help with the lighting. I knew what I wanted, but I didn’t know exactly how to achieve it. The assistant and gaffer helped me, but if they did something I didn’t like, I told them so. I couldn’t tell them exactly how to use a 5K or 10K, but I learned while doing it.

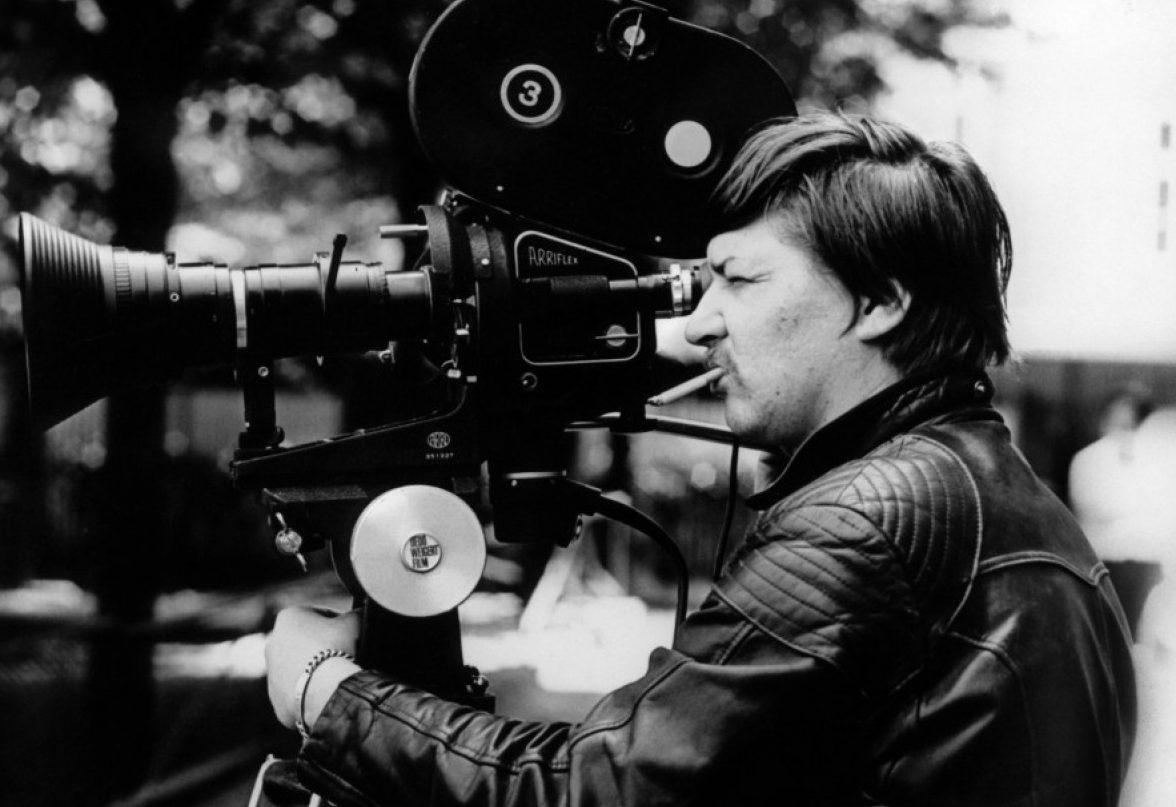

After mastering the basics of his craft, Ballhaus began honing his skills. Fate intervened while he was producing, directing and shooting a documentary in Ireland. He received a phone call from a friend, Ulli Lommel, who was in Almería, Spain, preparing to produce and act in a Western titled Whity (1970). “Ulli asked me, ‘Do you like Fassbinder?’ I said, ‘Yes, why?’ And he replied, ‘Do you want to shoot a movie with him?’ I answered, ‘Sure, when does it start?’ He said, ‘You should be here in two days!’ Two days later, I arrived in Almería to meet Mr. Fassbinder.”

Now ranked among the greatest German directors, Fassbinder was much less experienced than Ballhaus at the time. However, he was well on the way to earning a reputation as a brilliant filmmaker with a mercurial and often abusive personality. Working at an almost superhuman pace, Fassbinder would ultimately direct 43 films before dying of an apparent drug overdose in 1982, at age 37. He took a jaded view of human nature and could be downright sadistic with colleagues and friends. On nearly every picture, he worked with the same group of people, over whom he exerted a Svengali-like influence and control. He often let his mood swings dictate his casting choices, handing plum roles to those who pleased him and relegating offenders to secondary parts. After Ballhaus accepted the job to shoot Whity, he soon began wondering what he’d gotten himself into. “Fassbinder and I got off to a pretty rocky start. He saw me as a TV guy and never wanted to hire me in the first place. I think he was also a bit insecure because I had shot a lot more movies than he had. I must say, he didn’t treat me very well. There was one scene where I was concerned because we were jumping the line, and I told him I couldn’t put the camera where he wanted it. He reacted by asking the producers to fire me. I didn’t unpack my suitcase for two weeks because I thought, ‘This isn’t going to last long.’”

Lommel confirmed that Fassbinder was determined to “torture” Ballhaus at the outset. “Fassbinder wanted Jost Vacano [future ASC] to shoot Whity, but he was unavailable. When Michael arrived, Rainer said to me, ‘Tell him to go to hell — I want Jost!’ He had no choice but to try out Michael, though, and he gave him one of the most difficult setups ever. It was a four-minute traveling shot between five characters with a lot of focus shifts, and it was almost impossible to do. I knew it was one of Fassbinder’s sadistic ideas; he wanted to see Michael fail. He asked Michael how long it would take him to get [the scene] together, and Michael replied, ‘Just give me a couple of hours.’ When Fassbinder returned, they did a few takes. After each one, he would ask Michael, ‘Was that okay for you?’ And Michael would say, ‘Yeah, that was fine.’ Fassbinder just grinned triumphantly, expecting the worst. A couple of days later, Rainer and I watched the dailies of that scene. When the lights came on, he stood up with tears in his eyes, hugged me, and said, ‘Ulli, this guy is a fucking genius!’ That was the start of their long and beautiful relationship.”

After passing this test, Ballhaus quickly came to recognize Fassbinder’s skill as a filmmaker. “I knew right away that he was very, very talented. Everything he suggested was great. He often tried to make things as complicated as possible, but I found I could cope with him and his ideas. He never said anything complimentary to me when we looked at dailies, though. He was very rough.

“Looking back, he was the most important thing that happened in my life during that period. First of all, he was the guy in Germany at the time, because he did the most exciting movies. He had great stories, most of which he wrote himself, and he pushed me all the time. He worked very fast, so I always had to be well prepared, because he never gave me much time. On most of his movies, the longest schedule we had was around 20 days. We actually shot The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, which is over two hours long, in 10 days! Because we did those movies with almost no money, we didn’t do that many takes and didn’t shoot a lot of coverage. The pay was very low, but we did it because Rainer was very good, and it was exciting to work with him.”

Over the course of their collaboration, Ballhaus maintained a discreet distance from Fassbinder’s inner circle. “I had a family, and I didn’t want to be dependent on him the way some of the others in his group were. That’s why I shot films with a few other directors while I was still working with Rainer. He always hated that, though; he got jealous and often tried to punish me for it.” To keep the relationship stable, Ballhaus did his utmost to realize Fassbinder’s visual ideas, no matter how complex. This willingness to do “whatever it took to get the shot” paid dividends not only with Fassbinder, but also with all of Ballhaus’ subsequent collaborators. “I try never to tell a director, ‘No, I can’t do that.’ I’ve always felt that if someone has an idea, I want to fulfill their vision. Sometimes it takes a little more time or can be a little expensive, but if someone can think up the idea, there’s usually a way to accomplish it. Fassbinder often asked me to do tricky moves or tricky lighting, and I always found ways to do them. If you like an idea and really want to do it, you can.”

To be sure, the films Ballhaus shot for Fassbinder reveal the merits of this attitude. In Whity, for example, there are a number of stunningly photographed scenes that emerged from the duo’s willingness to experiment. The film was Ballhaus’ first in the anamorphic format, and he made maximum use of the wide frame. The constantly gliding camera, dramatic zooms and stylized lighting not only serve the story — which concerns the bizarre relationship between a mulatto servant and a wealthy, dysfunctional family in the American Southwest of 1878 — but also add an ironic subtext to the picture’s Western settings and motifs. The movie also marks the first appearance of the famous “Ballhaus circle,” a 360-degree dolly move that the cinematographer frequently used to highlight key moments in his films. In Whity, this move occurs when the servant (Günther Kaufmann) insults his prostitute girlfriend (Hanna Schygulla) by offering to pay her; to underscore Whity’s faux pas, the camera glides around the bed he occupies, lingering on the money in his outstretched hand to create a frozen moment of dramatic intensity. “The idea behind my circular dolly moves is to treat a special scene in a special way,” said Ballhaus. “I try to find an appropriate scene for the circle in every film I do.”

The making of Whity was so chaotic that it inspired Fassbinder to make a whole movie about the pitfalls of filmmaking. Titled Beware of a Holy Whore (1970), this angst-filled exploration of ennui concerns a director and production team who find themselves stranded in an Italian hotel, mid-shoot, when they run out of film stock and funding. Left to their own devices, they get drunk, have sex, and let their neuroses run amok. Holy Whore is filled with wry references to Fassbinder’s previous movies and offers uproarious insights into the dynamics of his filmmaking troupe. Ballhaus escapes this scrutiny relatively unscathed, although his onscreen counterpart does receive a tongue-lashing or two from the Fassbinder character. “Thankfully, most of the incidents depicted in Holy Whore didn’t involve me,” Ballhaus said. “When we were shooting Whity, my wife and kids were there. I had to go to bed at a reasonable hour because I had to get up very early in the morning. I usually heard all the wild stories later. I didn’t have a clue about what was going on because I was concentrating on my job! You’ll notice that my character only appears briefly in Holy Whore, because I was never part of the funny business.” (He admits, however, that he did have to dodge a few Cuba Libres hurled by Fassbinder and his associates.)

Ballhaus’ other films with Fassbinder are also notable for their craftsmanship and visual ingenuity. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), a hothouse drama about a lesbian fashion designer’s triangular relationship with her mute, masochistic assistant and a beautiful model, was adapted from a Fassbinder play and shot entirely in one room at a real location. “The apartment was pretty small, so there weren’t a lot of different angles to exploit,” Ballhaus recalled. “Instead, we concentrated on the atmosphere, on the lighting, and on creating nice close-ups and two-shots. We had to come up with interesting shots that would connect the people who were in this small space. We used a lot of deep focus, and we also tried to move the camera whenever possible. There was not a lot of cutting, and some of the shots were four minutes long, which was the longest you could go with a mag that held 300 feet of film.”

Fox and His Friends (1974) is notable for its frank presentation of homosexuality. Although Ballhaus once dismissed this compelling picture as “pretty awful,” he now concedes that “you do learn a lot about what the characters think and feel, and what their whole world is about.” Eagle-eyed viewers may notice that the film’s luridly lit gay bars foreshadow a lighting style that Ballhaus later applied to some of the bar scenes in Scorsese’s films, particularly GoodFellas.

Originally made for German television, Martha (1974) is fascinating for some of the stylized techniques used to tell the tale of a high-strung housewife (Margit Carstensen) terrorized by her domineering husband (Karlheinz Böhm). Mirrors are used to great effect, and careful compositions and camera moves help to convey Martha’s gradual subjugation. The film also features one of Ballhaus’ most innovative 360s, which occurs during a scene in which Martha first encounters her future husband and tormentor. “Rainer said, ‘This is a very important scene, and the audience should really remember the moment when these characters meet for the first time. What do you think we should do?’ I thought about it and suggested a 180-degree dolly move around them. He replied, ‘Why not go all the way around them?’ That was a problem, because the square where we shot the scene had a slope, and when you lay down 360 degrees of dolly track it has to be level. To level it out, we had to raise a portion of the track about a foot off the ground and have the actors step over it. Then, when we tracked around, Rainer made the actors circle each other in the opposite direction, so it became a sort of double move. It was a great effect.”

For maximum enjoyment of this movie, viewers should take note of Martha’s address in the film, 21 Douglas Sirk Street — an homage to Fassbinder’s favorite director — and watch closely for Ballhaus’ cameo as a tongue-waggling lecher. Laughing uproariously at this memory, Ballhaus recalled, “I told Rainer I would never do that in real life, and he said, ‘So do it in a movie!’”

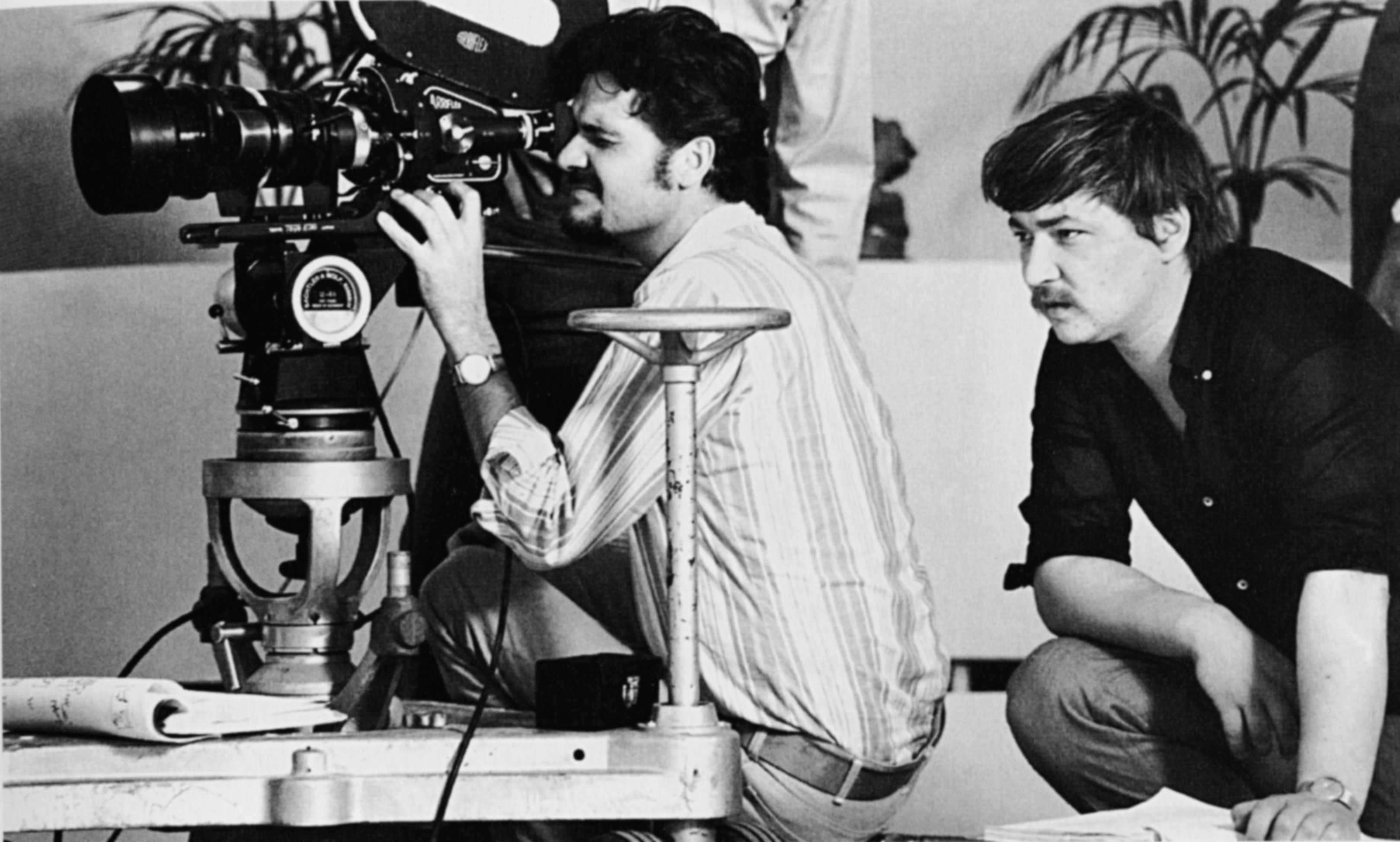

Ballhaus is particularly proud of his work on Chinese Roulette (1976), the story of a young girl who gets revenge on her callous parents by forcing them to endure a humiliating truth-telling game that exposes their most personal flaws and failures. With its use of a roving camera, glass reflections and very precise mise en scène (featuring compositions that Ballhaus often reframed on the fly), Chinese Roulette is a tour de force of graceful camerawork. “After we picked the actors and the location, Rainer went to Paris for two weeks and wrote the script,” Ballhaus remembered. “He came back and prepped for two weeks, and we shot it in four weeks. He cut it in two weeks. So going from the first idea to the finished movie took no more than three months. It was an interesting film that was fun to shoot because the camera becomes like a character in the movie. It’s very stylish, and all of the moves were very well planned and executed. The blocking was very rigorous.” (On a side note, Ballhaus’ wife, Helga, served as the show’s production designer.)

After photographing The Stationmaster’s Wife (1977), notable for its long pans, complicated setups and expressive camera moves, Ballhaus and Fassbinder mounted The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978), which earned many awards and became Fassbinder’s biggest international hit. Starring Schygulla in the title role, the movie follows a World War II bride’s journey of survival in postwar Germany. The film begins, quite literally, with a bang — a moment Ballhaus would never forget. “The first shot of the movie shows Maria and her husband signing their marriage certificate in a rubble-strewn street. Rainer wanted the explosion to happen right after they signed the certificate so the piece of paper would get blown away. This Italian special-effects guy set up the charge with a little bit of powder, but it just gave off a small puff. Fassbinder complained, so the guy added some more powder, but Rainer was still not happy with the results. So then the guy got pissed and put too much powder in the charge, and when it exploded, I flew backwards along with the camera, which was ruined!”

Ballhaus maintained a desaturated palette for the wartime scenes and gradually added more color and illumination as the war years fade and Maria’s prospects brighten. He was aided in this strategy by his wife, who once again served as production designer. “Maria Braun was the first movie I shot with Fuji film stock,” he noted. “I used the high-speed stock. I used very little light and shot wide open sometimes. We did some scenes basically with candlelight. Helga was careful to keep the colors very muted in the early scenes because those were very poor times in Germany.”

Maria Braun marked the end of Ballhaus’ collaboration with Fassbinder, whose drinking and drugging had begun to take a heavy toll. “I remember discussing a particular scene with him,” said Ballhaus. “We planned to do about eight shots to get the sequence, and when I started preparing it and lighting it, he went off to his trailer. About half an hour later, he came back after taking a little sniff of cocaine and said, ‘No, we won’t do it this way, we’ll do it in one shot.’ You have to be very patient in those situations, but after so many years together, my patience was running out.”

The conflict boiled over while Ballhaus was prepping Fassbinder’s next project, the 15-hour television opus Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980). “I had my deal in place, but before I started working on Alexanderplatz, I shot a movie with another director. When I came back to Berlin to do a scout for Rainer, he decided to punish me again for working with someone else, and he wouldn’t speak to me directly. He would say to his assistant, ‘Tell the cameraman this and that.’ He had played these games before with others, and I thought it would be just for one day, but the next day it was the same thing. I thought, ‘My God, I have to work with this guy for one whole year, and he’s behaving like this?’ I decided I couldn’t do it anymore. I had no other jobs lined up, but I quit. The producer tried to talk me out of it, because he knew that whenever Fassbinder flipped out and didn’t show up, my crew and I could simply continue with the work. But I stuck to my guns.”

In 1982, Ballhaus struck out in a new direction by moving to America. While staying at his old friend Lommel’s house, he received a phone call from his wife, who told him Fassbinder had died. “It was shocking. Ulli and I both cried. Rainer always said that he would never be old, that he would have a short life, but it was still a blow when we got the news.”

Ballhaus’ first job on U.S. soil was Dear Mr. Wonderful (1982), a German-financed, New York-based project directed by Peter Lilienthal, an old friend from his TV days. His first full-fledged American production was John Sayles’ 1983 romance Baby It’s You. “I was very nervous to do my first American movie, because all of a sudden I was on my own, and I didn’t know if John would have the same ideas and feelings about the story. I felt a little sick to my stomach, but then we got started, and for me it was a major revelation that there was not such a big difference between Germans and Americans — they laugh and cry about the same things. That’s why American movies are so successful all over the world. It was great working with John, and I had a very good time with the actors.”

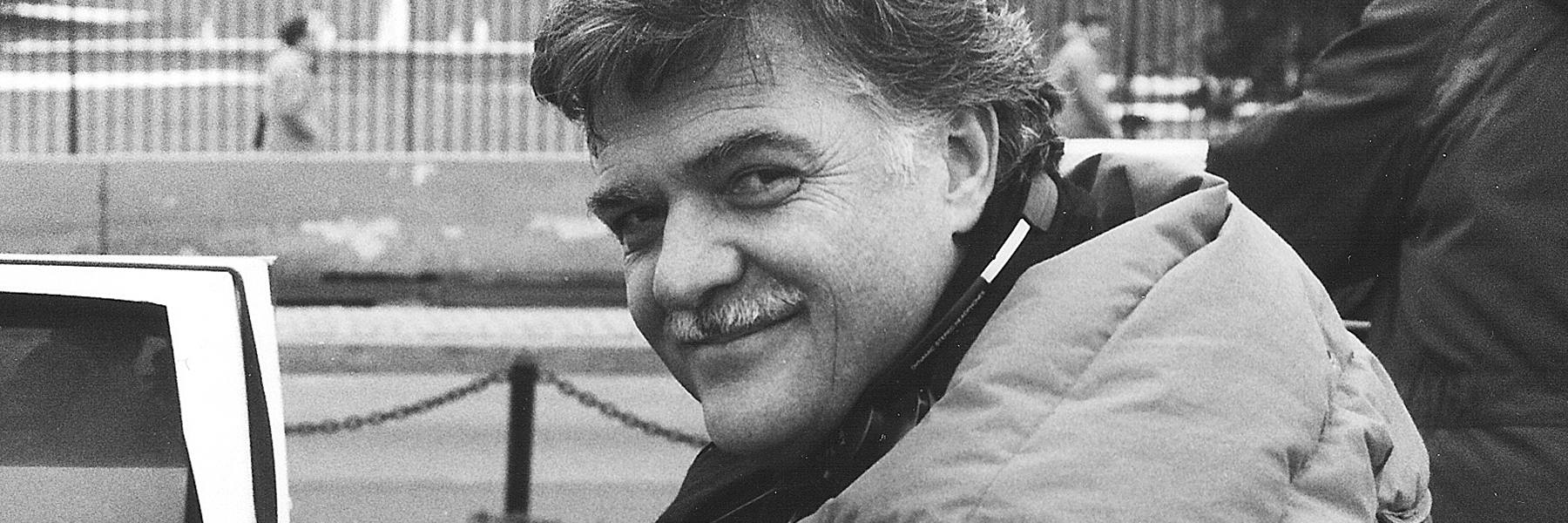

Two of the film’s producers, Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne, later helped Ballhaus connect with Scorsese. Ballhaus had observed Scorsese at the 1981 Berlin Film Festival, where the director presented Raging Bull and made an impassioned speech about film preservation. “I thought Raging Bull was the best movie I had ever seen,” Ballhaus recalled. “It really blew me away. Later, while Marty was making his speech, I turned to my wife and said, ‘I want to work with that guy someday.’” The cinematographer got his wish in 1984, but only after a false start. “My first movie with Marty was supposed to be The Last Temptation of Christ. It was at Universal and was a big-budget movie. I met Marty in Los Angeles, and we liked each other immediately. I went on a scout to Israel, and we already had about 300 costumes ready. Three weeks later, Universal pulled the plug, and I went from being in heaven to falling hard to Earth. I was devastated because I thought I might never work with Marty again. But then After Hours came along.”

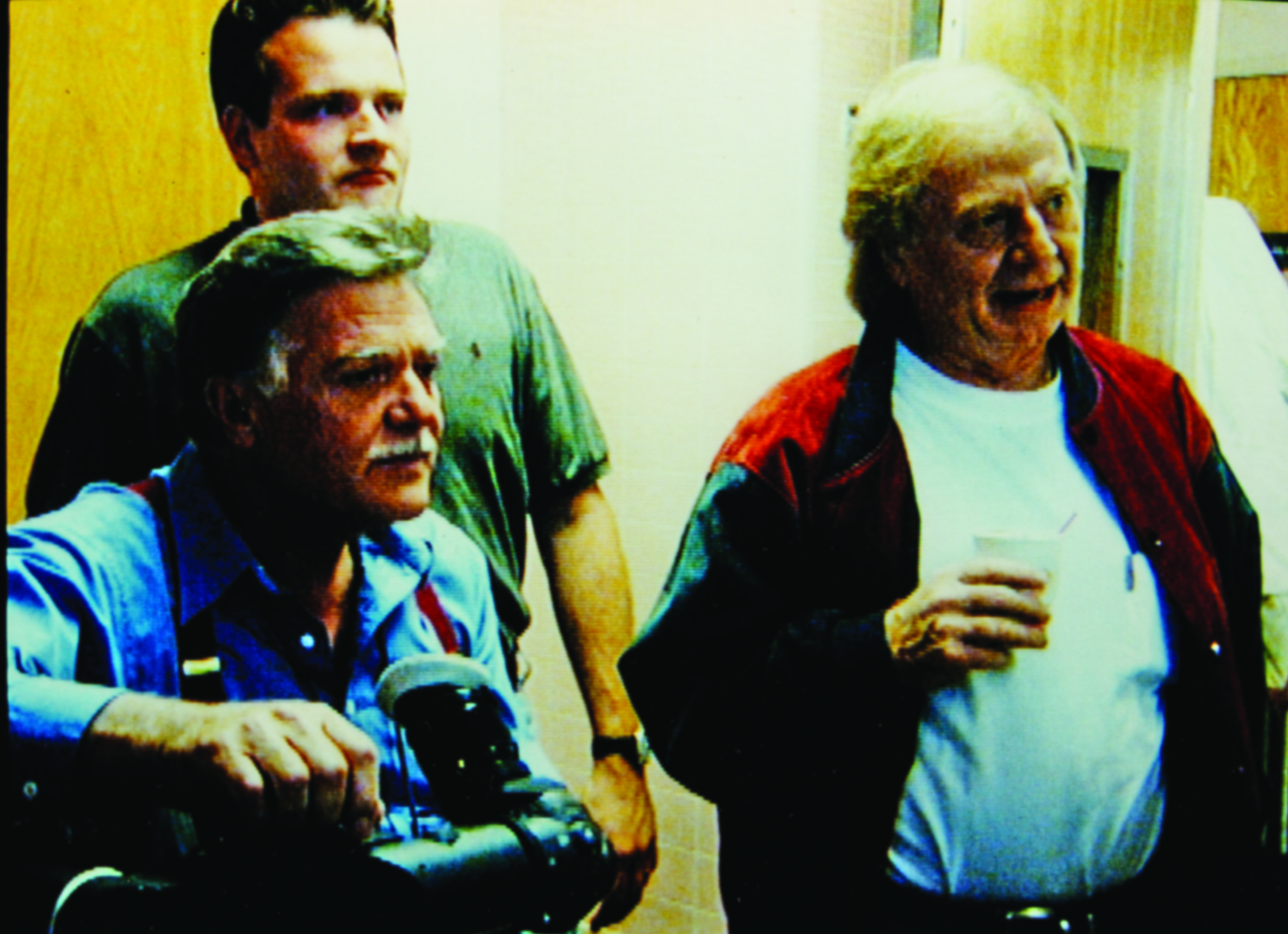

Made for $4 million over 40 nights, After Hours (1985) was a project that played to Ballhaus’ strengths. A pitch-black comedy filled with homages to Hitchcock, Lang and German Expressionist lighting, the picture required both artistry and speed. “When Marty got the offer to do After Hours, he said to [producer] Amy Robinson, ‘Here’s my shot list. Show it to Michael and ask him if he can do it.’ I looked at the list very carefully and counted the shots, and there were 600. I told Marty, ‘I can do it, but can you do it? If you are willing, I think we can do it together.’ And that’s how it happened. I remember setting up a shot on the very first night. Marty went back to his trailer, and 15 minutes later they called him and said, ‘Hey, Michael’s ready.’ From that moment on, he never left the set because he never had time to go back to his trailer again!”

Looking back on that shoot, Scorsese credited Ballhaus for reinvigorating his approach to cinema at a crucial point in his career. “When Last Temptation was cancelled, I had to rethink who I was and the kinds of films I wanted to make,” the director told American Cinematographer. “I’d gotten myself in a slower frame of mind, where I felt encumbered by bigger productions. I started planning to do a smaller film again, an independent film, and the experience I had working with Michael was a sort of rebirth for me. On After Hours, we had the chance to see if we could make a film with the energy level I had when I did Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore or Taxi Driver. The great thing about Michael on that film was that he was so enthusiastic about my shot designs. He was very, very helpful in getting exactly what I wanted. We had a lot of fun figuring out what type of lens to use, how fast or slow to move the camera and in what direction. It was like rediscovering how to make movies — together. He really gave me back my faith in myself about how to make films.”

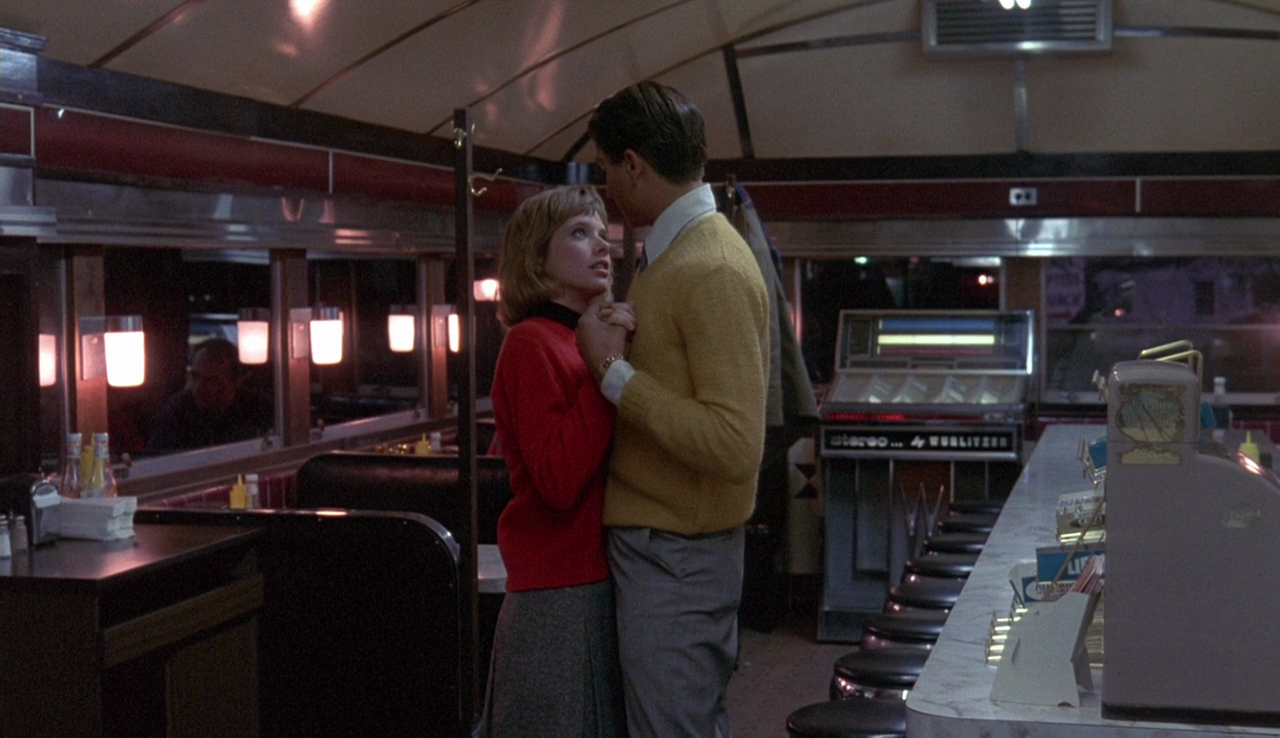

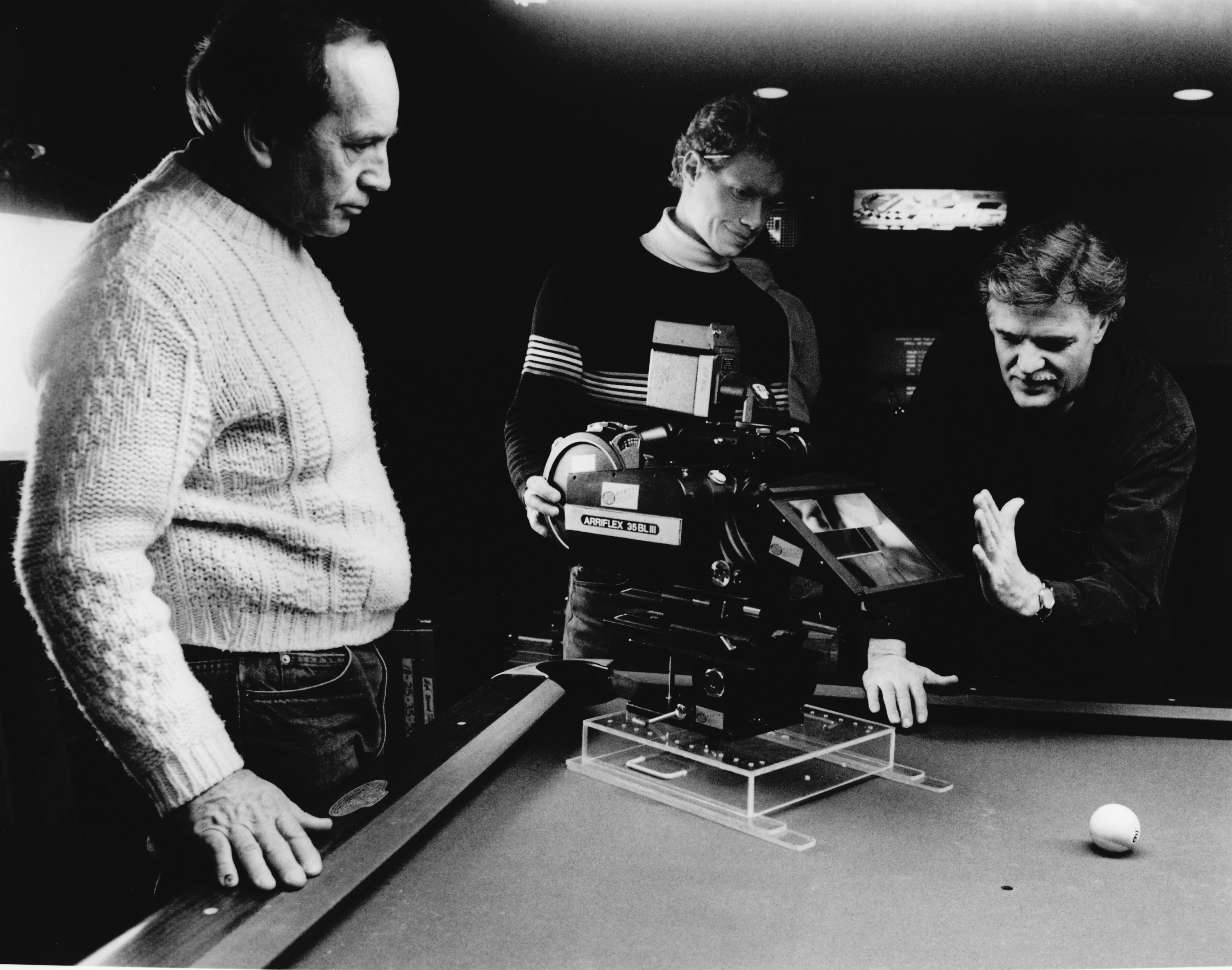

That sense of renewed enthusiasm is also apparent in the duo’s second collaboration, The Color of Money (1986; see AC Nov. ’86), which Ballhaus ranks among his favorite projects. The dynamic, fast-paced sequel to The Hustler allowed the cinematographer to create some extremely flashy shots on, above and around pool tables — including a dazzling array of his beloved circular and semi-circular dolly shots. Working in real Chicago poolrooms, Ballhaus lit the games primarily with low-hanging fluorescent light banks that allowed him create a moody, dramatic ambience. “I lit the movie the way these pool halls were lit. I illuminated the tables’ felt surfaces, letting the areas beyond the tables fall off into darkness.” Scorsese credited Ballhaus — and stars Paul Newman and Tom Cruise, who became deft with their pool cues — for helping to make some of the show’s trick shots look easy: “Sometimes I’d think it was going to take 17 or 18 takes to get a ball to go into a certain hole, but then we’d nail it in two takes!”

By contrast, Ballhaus did endless takes with director James L. Brooks on Broadcast News (1987; AC April ’88), but was rewarded with his first Academy Award nomination. “Jim is very, very good, but he does a lot of takes — I’ve never done as many takes with another director,” he said, noting that the film was shot at about 40 locations in and around Washington, D.C. “He appreciated the fact that I never used a lot of setup time; the whole newsroom set was basically pre-lit, so he had a lot of time to work with the actors.”

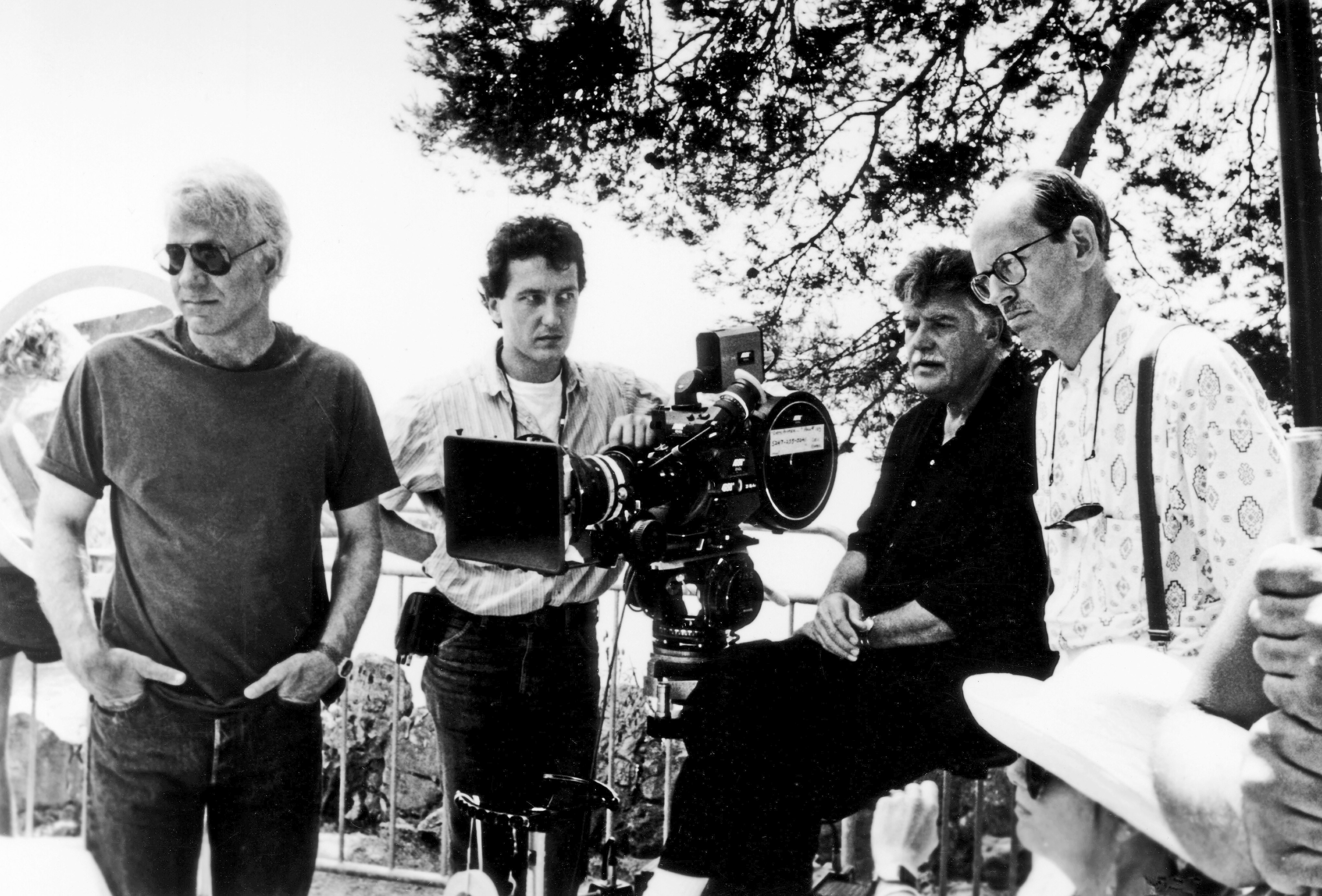

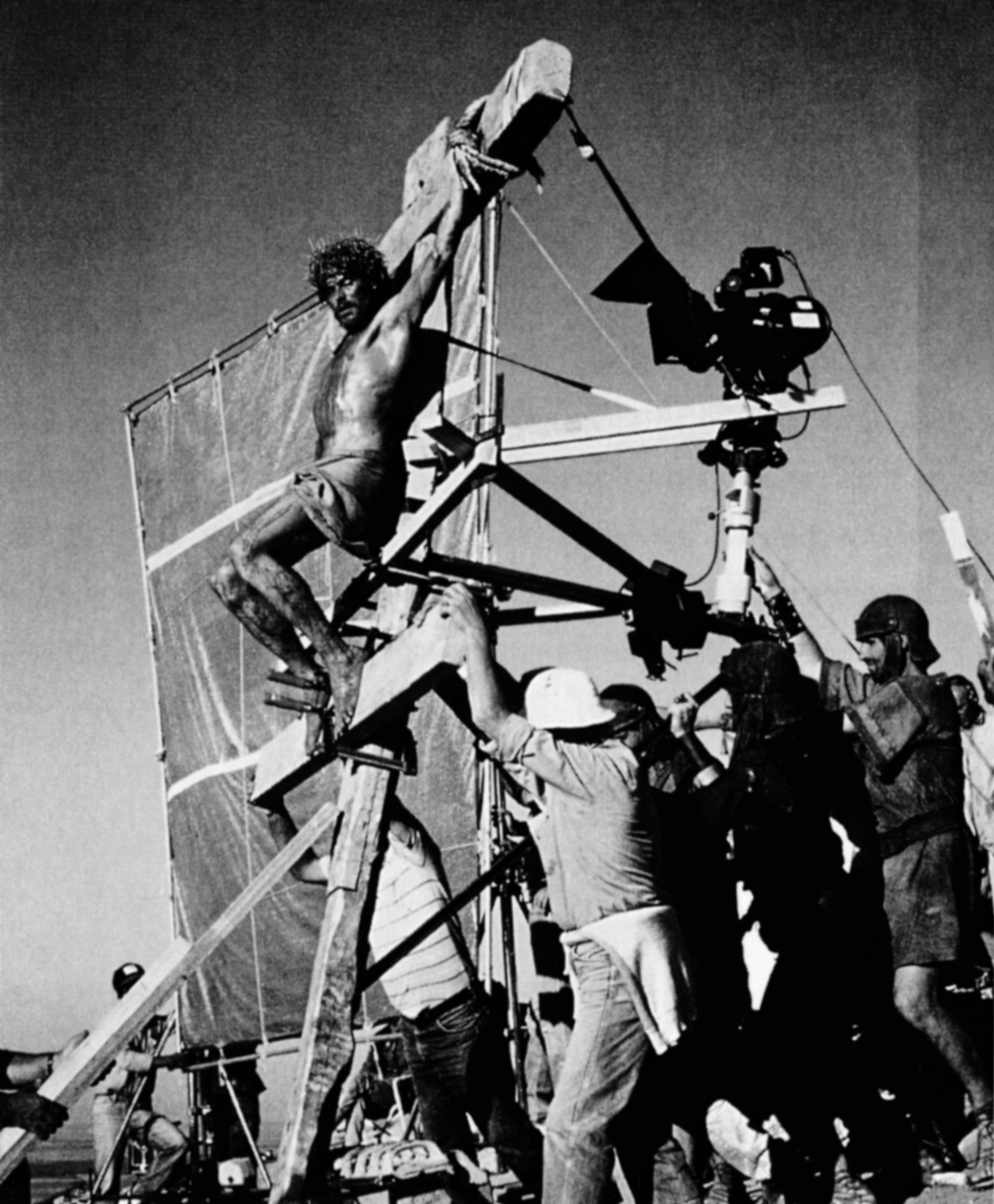

In 1988, Ballhaus and Scorsese reteamed on The Last Temptation of Christ, which had been resurrected with a much smaller budget and a tight 60-day schedule. Shooting on location amid the soft, dusty light of Morocco, Ballhaus and the crew worked very long days to help Scorsese achieve his passion project. “It was tough, and we all worked really hard, but we did it for Marty because he wanted to make the movie so badly. There was a great atmosphere on the set. Every morning we started rolling with the first light, and we were still shooting when the sun went down.”

Scorsese noted that he and Ballhaus relied on faith to capture one of the film’s most memorable shots, which approximates Christ’s point of view as he is raised up on the cross. “I designed that shot on paper, but then we had to figure out how to do it with the actual cross,” said the director. “Once we determined the best way to mount the camera, we had to hope for the best, because we didn’t have video assist and no one could look through the lens while we were doing it. I originally had around 75 setups planned for the crucifixion scene, but we only had two days to shoot it. When I sat down with Michael to discuss it, he said, ‘You’ve got to start thinking about what your most essential shots are. We can do it if we start exactly as the sun is coming up and if we assign a precise amount of time to each shot. If we find that a shot requires five minutes and we’re still shooting after seven or eight, we’ll have to abandon the shot and move on.’ We blocked out about 45 minutes for the longest shot, and the others ranged from five minutes to 20. Michael based this approach on what he’d done with Fassbinder, and he helped me cut 75 setups down to 50.”

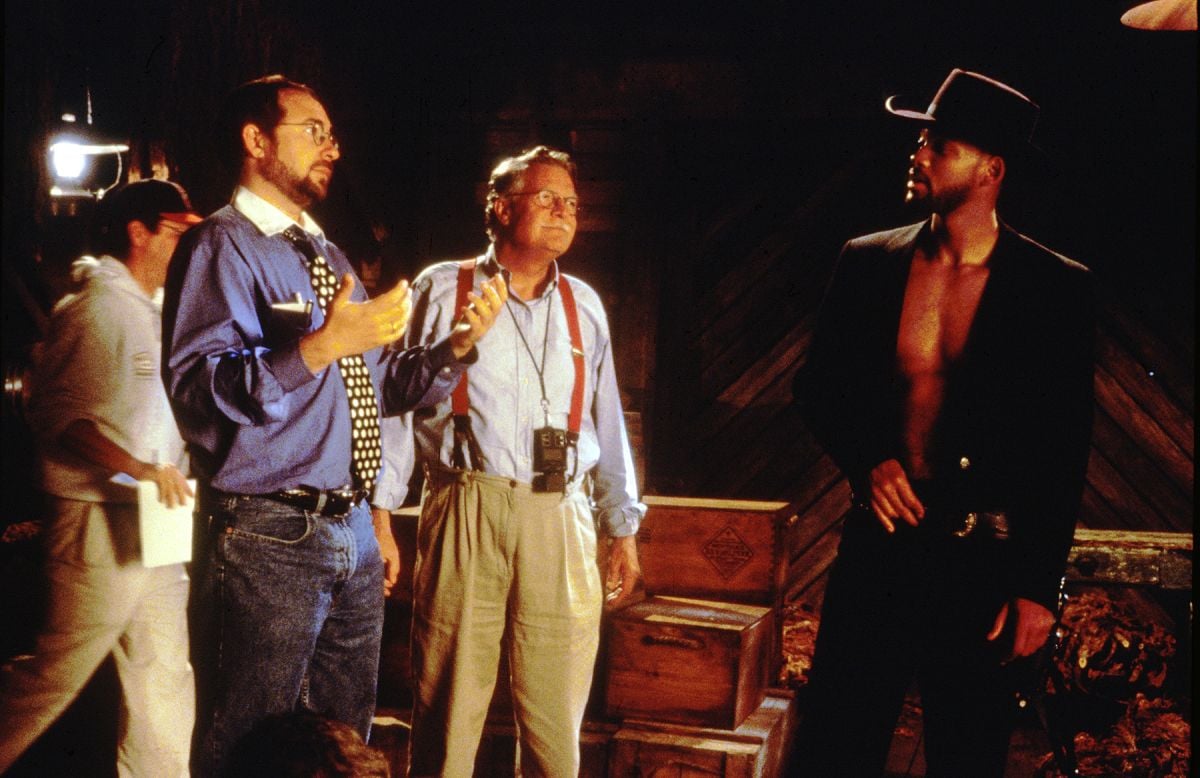

Ballhaus earned his second Oscar nomination for The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989; AC Nov. ’89), the story of two struggling nightclub musicians (played by Jeff and Beau Bridges) whose act takes off after they team up with a female singer (Michelle Pfeiffer). His strategy for this film was to use “deliberately ugly” lighting for early scenes set in tawdry venues — “a lot of cheap colors, green and pink gels” — and then show the musicians in a steadily improving light until they reach their apex during a gig at a spectacular resort hotel, where Pfeiffer belts out a showstopping rendition of “Makin’ Whoopee” from atop a grand piano. This scene, of course, was the one Ballhaus singled out for his signature 360 move, which turned the sequence into a classic. “We did the piano scene in six hours because it was well-rehearsed,” he said. “We had it choreographed and then rehearsed it with a video camera. I had a lot of freedom on that movie. The director, Steve Kloves, was not experienced, but he also had no ego. He was a wonderful collaborator who really took care of the actors.”

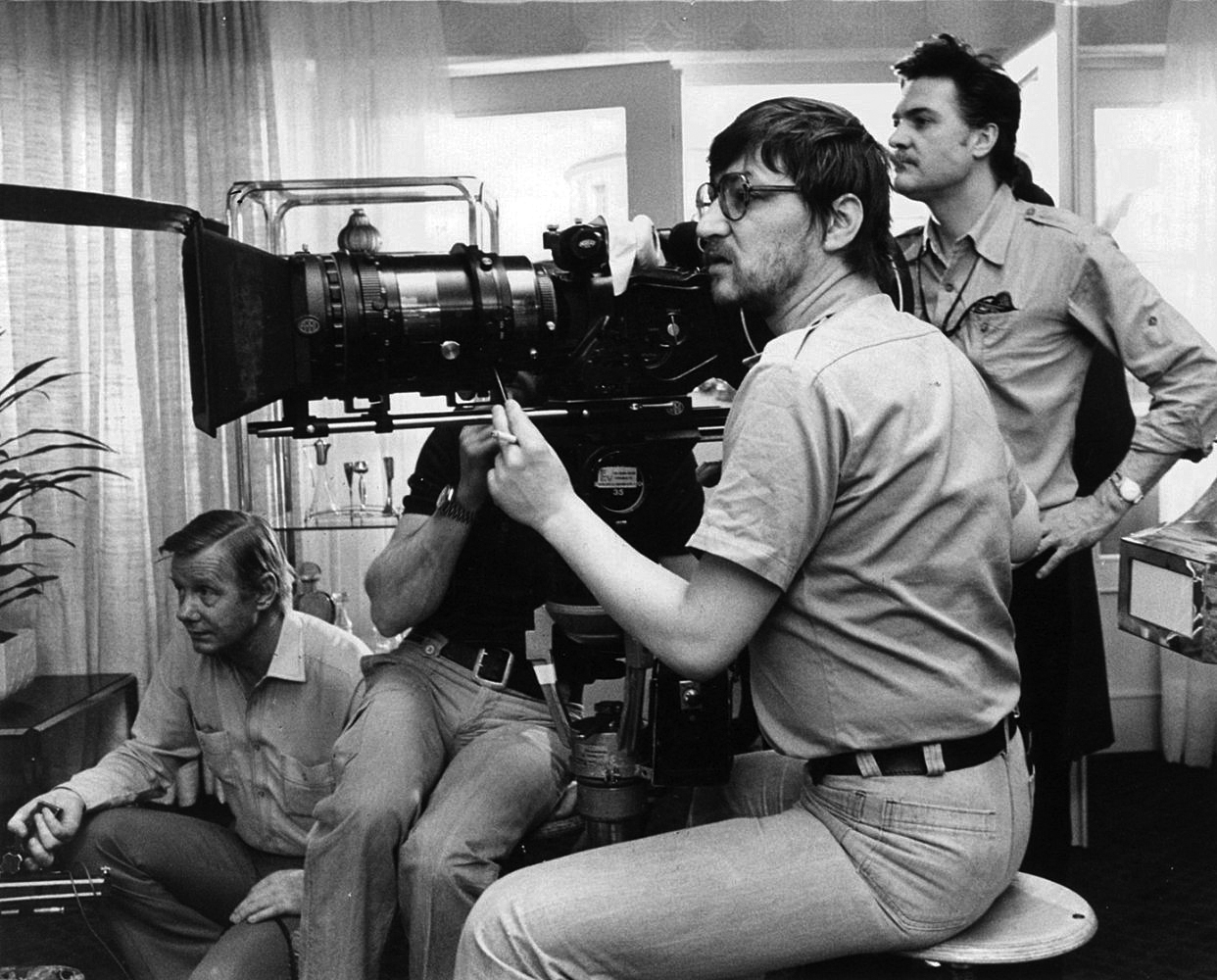

During the 1990s, Ballhaus cemented his reputation as one of the world’s top cinematographers. He and Scorsese began the decade in spectacular fashion with GoodFellas (1990), a turbo-charged gangster saga that became an instant landmark of the genre. If The Godfather was high opera, GoodFellas was street theater at its most muscular and intense. Interviewed for the book Martin Scorsese: A Journey, Ballhaus told author Mary Pat Kelly, “This is totally different from what I’ve done so far on other movies. We are using a lot more wide angles, up to extreme wide angles, and extreme high angles. We’re using a lot of long lenses, so there’s nothing in between — it’s like 24mm or 28mm or 18mm, and then it’s 50mm and 85mm. The light is not soft and not bounced. It’s more harsh, direct light, with a lot of darkness in it. It’s rich colors — rich reds, rich blacks. It’s not smooth and soft; it’s dark, shadowy, direct lighting.”

Among the movie’s many exhilarating moments is a three-minute Steadicam shot that follows mobster Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) and his girlfriend (Lorraine Bracco) into the Copacabana nightclub. After crossing a street and entering the club through a side door, the couple make their way down a winding hallway, pass through the kitchen and emerge into the main dining area, where deferential attendants escort them to a prime table in the front row. Ballhaus blocked out the complex timing with Steadicam operator Larry McConkey and assistant director Joe Reidy, with Scorsese making suggestions and adjustments. According to Scorsese, nailing this shot took “12 takes or so.” Ballhaus recalled his only frustration was that comedian Henny Youngman, who appears onstage as himself at the end of the shot, kept blowing his lines.

Later in the shoot, Ballhaus convinced Scorsese to add a subtly disorienting camera move to a diner scene in which Hill realizes that his supposed ally, Jimmy the Gent (Robert De Niro), may want to kill him. To convey that their relationship is shifting, Ballhaus executed a combination dolly/zoom that stretches the background beyond the two characters, recalling the classic acrophobia shots from Hitchcock’s Vertigo. “It’s a subtle effect,” Ballhaus noted, “but I wanted the audience to realize that this was a key turning point between these two characters.”

Ballhaus said that he would never forget his reaction to the final cut of GoodFellas: “It was so fascinating to see what Marty had done with the editing and everything else that I almost forgot I’d shot the movie! It was really brilliant.”

Scorsese and Ballhaus reteamed twice more during the 1990s, on the epic period films The Age of Innocence (1993; AC Oct. ’93) and Gangs of New York (2002; AC Jan. ’03). Polar opposites in tone, these two pictures — both set in 19th-century Manhattan — show Ballhaus at the height of his artistry. The former, an elegant adaptation of Edith Wharton’s acclaimed novel, presents an impeccably lit, painterly re-creation of New York high society during the Gilded Age. Gangs, a sprawling epic shot at Cinecittà Studios in Rome, details the street-level savagery between murderous criminal factions of a bygone era. “The Age of Innocence is one of my very favorites among all the movies I’ve shot,” he said. “It was a dream to work on — the costumes, the colors, the camera movement.” Ballhaus earned his third Academy Award for Gangs, and he graciously maintained that his job was made easy by “the incredible artistry of our production designer, Dante Ferretti, who built the most amazing sets.” (You can read AC‘s complete coverage here.)

During the rest of this productive decade, Ballhaus demonstrated his range by tackling comedy (Postcards From the Edge, What About Bob?), musical drama (The Mambo Kings), “courtroom noir” (Guilty by Suspicion, AC March ’91); classic horror (Bram Stoker’s Dracula, AC Nov. ’92); cerebral drama (Quiz Show); action-adventure (Outbreak, Air Force One) and politics (Primary Colors). Since 2000, he had dabbled in golf (The Legend of Bagger Vance), romance (Something’s Gotta Give), and more gangland violence with Scorsese (The Departed; AC Oct. ’06; complete story here).

Attempting to sum up his admiration for Ballhaus, Scorsese cited his good friend’s “courteous nature and positive, open attitude.” He added, “I always complain, but he finds the good side of every bad situation. Things sometimes become overwhelming, but he’ll always say, ‘Don’t worry, we’re gonna be able to do it.’ He always supports you emotionally and psychologically, and he always has a smile in the morning, which is interesting to me, because I don’t smile in the morning! He’ll always say something like, ‘Marty, today is an exciting day.’ And I’ll say, ‘Why?’ And he’ll answer, ‘Because today we get to do that great shot we discussed three days ago.’ Suddenly I’ll remember, ‘Oh, right, we’re doing the big tracking shot!’ He always reminds me that despite all the difficulties, we’re blessed to be doing this kind of work.”

Suffering from glaucoma, the cinematographer formally retired after shooting the drama 3096 Days (2013), directed by his second wife, filmmaker Sherry Hormann. He discussed this debilitating process in detail in his 2014 autobiography Bilder im Kopf: Die Geschichte meines Lebens (Pictures in the Head: The Story of My Life), which opens with the line “These are the memories of a man who has lived and worked with his eyes.”

Ballhaus previously penned the 2002 tome Das fliegende Auge (The Flying Eye), in which he detailed his career and elaborated on his many creative collaborations, noting in the end that “I’ve been in this business long enough. Forty years is definitely enough; I’ve made enough films, I think, and I would like to concentrate a bit more on young people.”

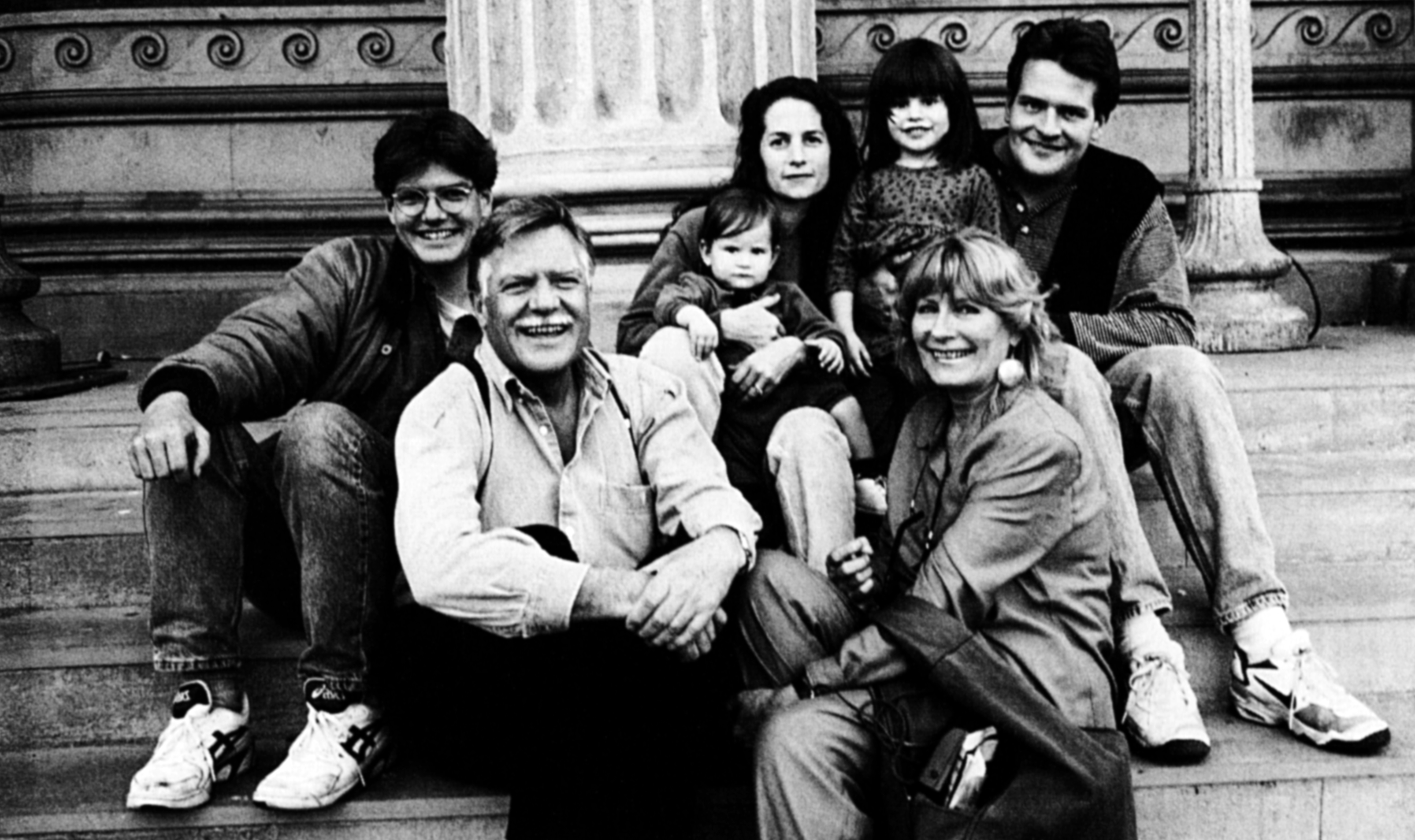

He is survived by his wife, Sherry, sons Florian Ballhaus, ASC — who worked for his father as an assistant and operator before becoming a cinematographer in his own right — and Jan Sebastian — an accomplished assistant director — as well as four grandchildren.

This story was based upon the feature profile “Full Circle,” written by AC editor-in-chief and publisher Stephen Pizzello, and originally appeared in the magazine’s February, 2007 edition.