Vertigo: Hitchcock’s Acrophobic Vision

Revisiting Hitchcock‘s classic tale of duality and obsession, photographed in VistaVision by Robert Burks, ASC.

Witty, rotund and very British, Alfred J. Hitchcock was one of fewer than a handful of movie directors whose name actually meant something to the public. Besides specializing in suspense, a typical Hitchcock picture offered beautiful women, Puckish humor, a prolonged chase and some strategically placed shocks. There were also Hitchcock pictures that were not typical. In the forefront of these is Vertigo.

Hitchcock earned his title of “Master of Suspense” in England during the 1930s. His pictures were well liked in the United States even then, when British films in general were poison at the box office. After coming to America in 1939, the director became increasingly more popular. However, long before 1957, when Hitchcock made Vertigo, his virtual immunity from criticism had dissipated. A picture in familiar Hitchcock style brought accusations of producing “the same old stuff,” but with any deviation, the same cynics advised him that “the shoemaker should stick to his last.” Caught in a no-win situation, Hitchcock alternated his traditional thrillers with some daring departures, such as the 1949 costume drama Under Capricorn, the “real-time” experiment Rope, the all-in-fun The Trouble With Harry (1956) and the all-grim and no-fun The Wrong Man (1957). That he had lately become a popular TV personality further eroded his position with critics even as it firmed his hold on the public.

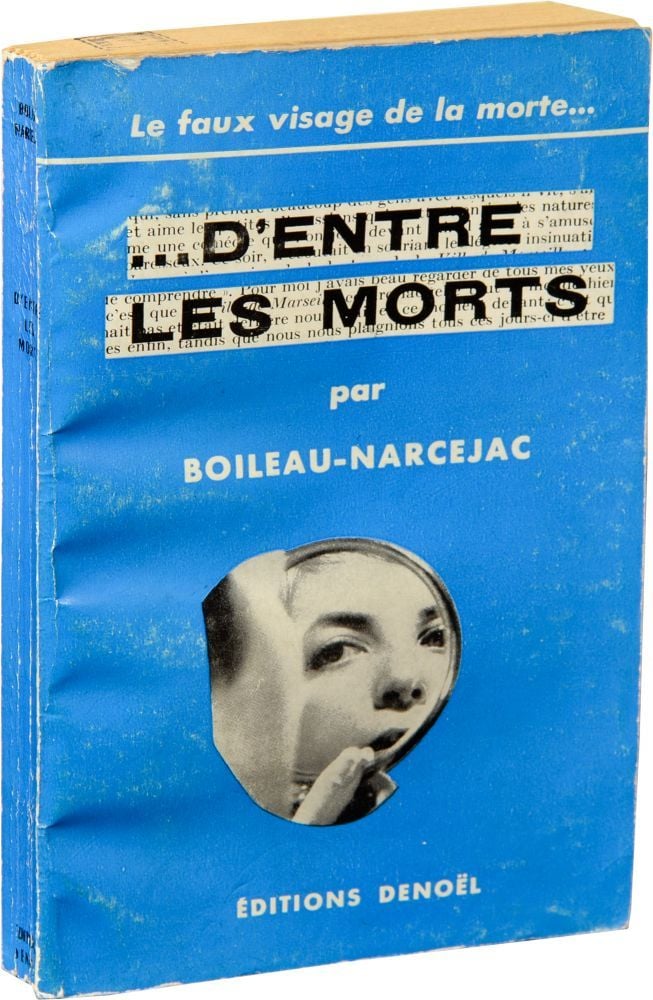

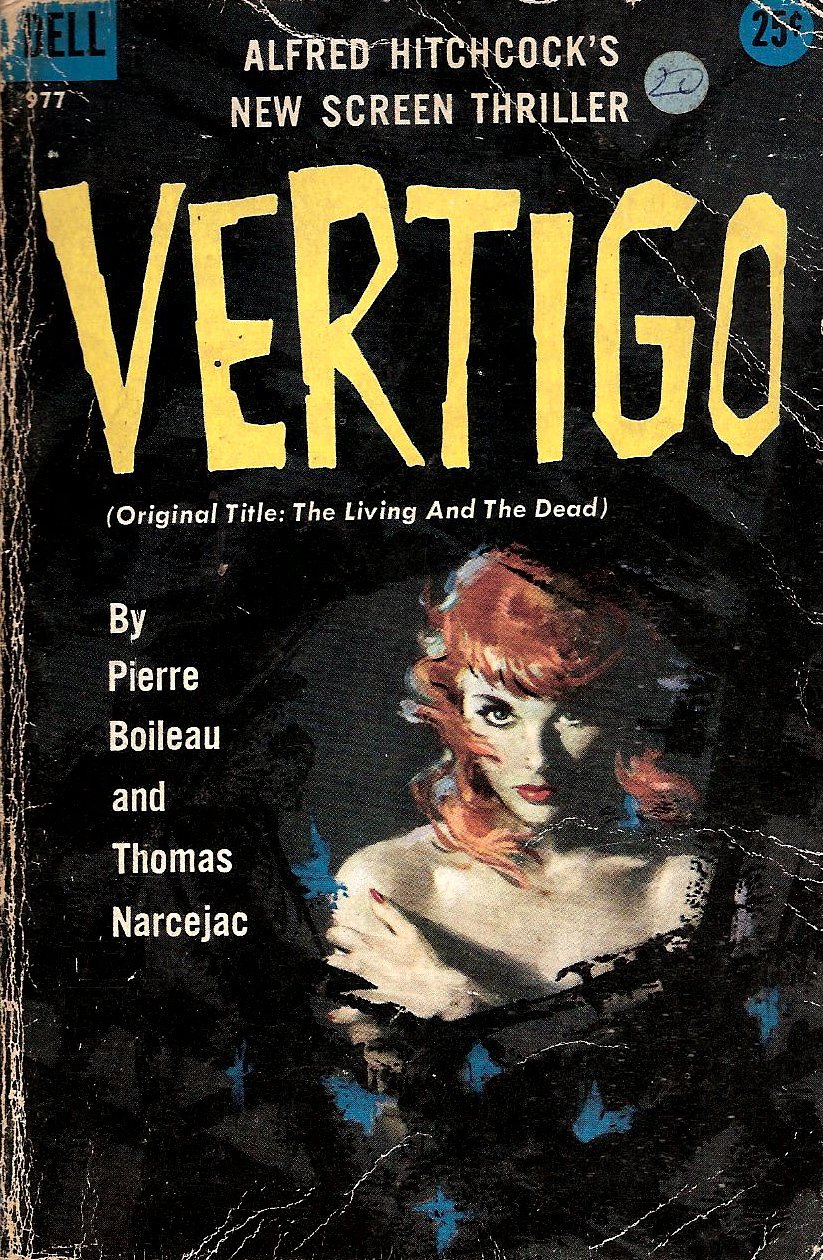

Vertigo is definitely off the beaten track for Hitchcock or anyone else, but like most of his pictures it uses one of his many phobias to induce terror. Its basis was a French novel, D’entre les Morts, by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, whose earlier Les Diaboliques had become a hit movie directed by Henri-George Clouzot.

Preproduction work began in October 1956 at Paramount’s Hollywood studios. Playwright Maxwell Anderson, author of Winterset and Key Largo, had been secured to write the adaptation. Before the end of the year, Anderson, who had changed the title to Darkling I Listen, delivered a script too arty, poetic and pretentious to film.

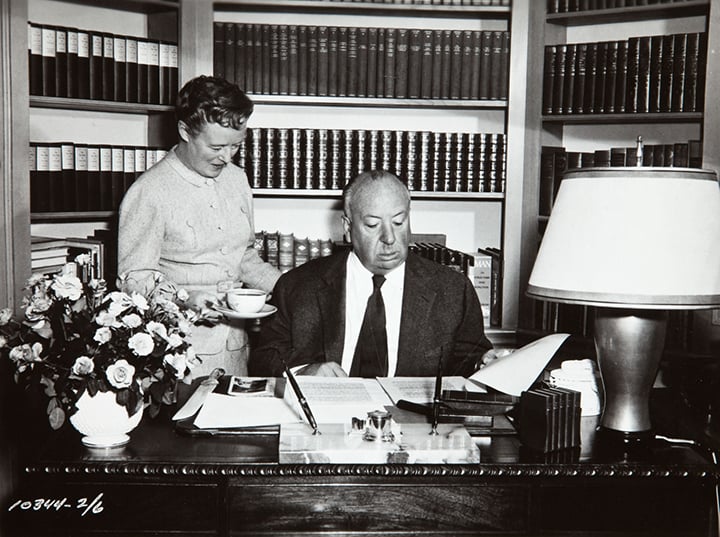

Prior to undergoing surgery for colitis and a hernia in mid-January, Hitchcock, on advice from Paramount’s head office, assigned British author Alec Coppel to write a new screenplay. The result, Hitchcock decided, was also unfilmable. On the advice of Kay Brown, a longtime story editor for David O. Selznick, the director hired Samuel Taylor, a San Francisco native who had written the twice-filmed Broadway success Sabrina Fair.

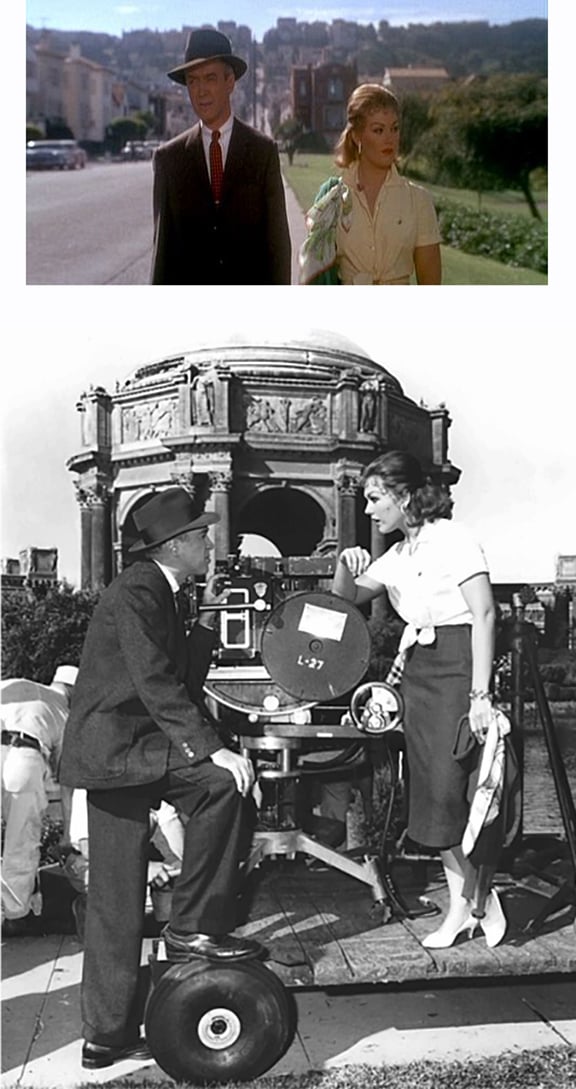

Hitchcock was brilliant at concocting individual scenes for a picture, but was unable to visualize the necessary connective tissue. He wanted Vertigo to take place in San Francisco because of its precipitous streets, unusual architecture and palpable atmosphere of mystery. He envisioned the mysterious leading lady, blonde and dressed in grays and white, as being almost a part of the city’s fog. Other Northern California locations and many dramatic highlights were also firmly in his mind.

Suspecting rightly that Hitchcock already knew what he wanted, Taylor wrote the new screenplay from scratch, without consulting either the novel or the other scripts, but working closely with Hitchcock. The two went to the locations to be used, absorbing the atmosphere and working out details. The resulting version, which was called From Amongst the Dead during production, uses the basic idea of the novel, but the book’s “surprise” ending is exposed about midway through the screenplay in order to favor suspense rather than surprise.

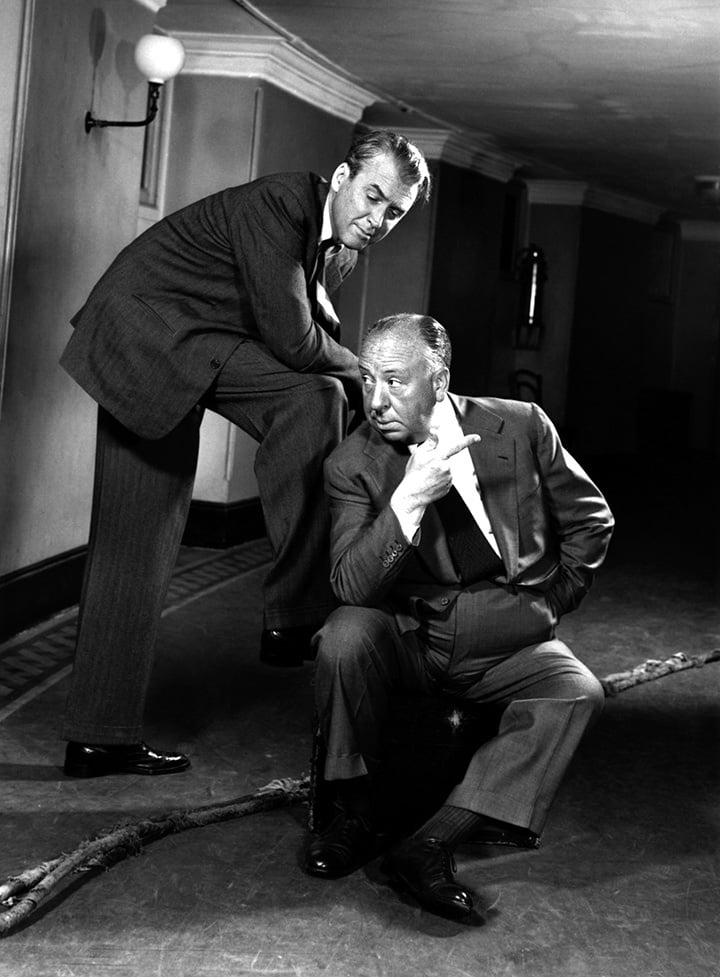

From the outset Hitchcock had decided upon James Stewart and Vera Miles for the leading roles. Stewart, who had thoroughly enjoyed working on three previous Hitchcock pictures — Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1955) — signed on without even asking what the picture was about. He soon had second thoughts. Years later he recalled, “It just wasn’t my kind of part. My kind of guy is an easygoing, bumbling sort of fellow like the ones in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or Rear Window.” Still later, after seeing Vertigo for the first time in years, Stewart said he only then realized what a great picture it was.

Hitchcock, certain that Miles would soon be one of the industry’s top stars, had placed her under an exclusive personal contract. Although driven to distraction by a heavy overdose of directional attention, she had given him a superb performance in The Wrong Man. Her makeup and hairstyle tests for Vertigo were begun early in November 1956, while designer Edith Head was planning her costumes. By February 18, 1957, the tests had been completed and Miles’ wardrobe was ready.

On March 11, Hitchcock again underwent major surgery, this time for gallbladder removal, and was bedridden for a month. While convalescing, he received a telephone call from Miles, who told him that she was pregnant and therefore could not appear in Vertigo. Hitchcock was enraged at what he considered a betrayal. This was the third pregnancy for the actress, who was married to the current movie Tarzan, Gordon Scott. The director never forgave his former protégé for giving up “her chance to become a great star,” and 20 years later was still complaining about what he perceived as her ingratitude, griping that her departure from Vertigo had cost him “several hundred thousand dollars.”

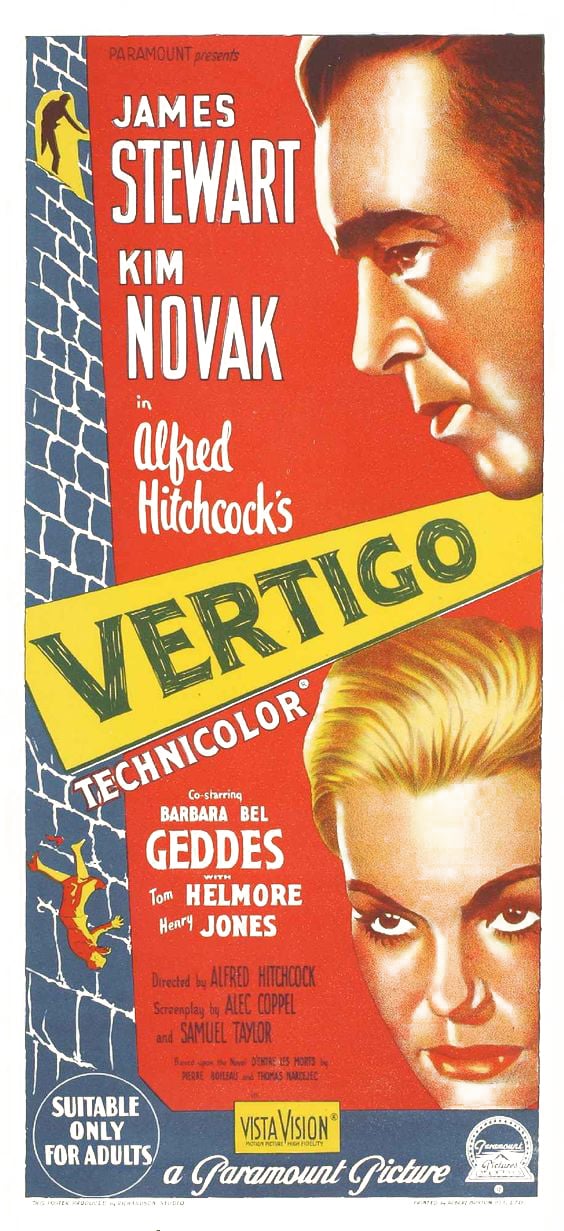

At the insistence of MCA president Lew Wasserman, Hitchcock agreed to bring in Kim Novak, a glamorous and highly paid Columbia star, to replace Miles. Harry Cohn, president of Columbia, agreed to loan Novak in exchange for borrowing Stewart later. The actress and the director were soon at loggerheads. First, she delayed production while she went on a vacation Cohn had promised her. Upon returning, Novak refused to work until she received her share of her loan-out fee from Cohn. She also objected to the gray-and-white costumes Hitchcock insisted upon and had her own preconceived ideas. Yet, despite the director’s oft-expressed lack of faith in Novak, she gave him a performance that could hardly have been bettered.

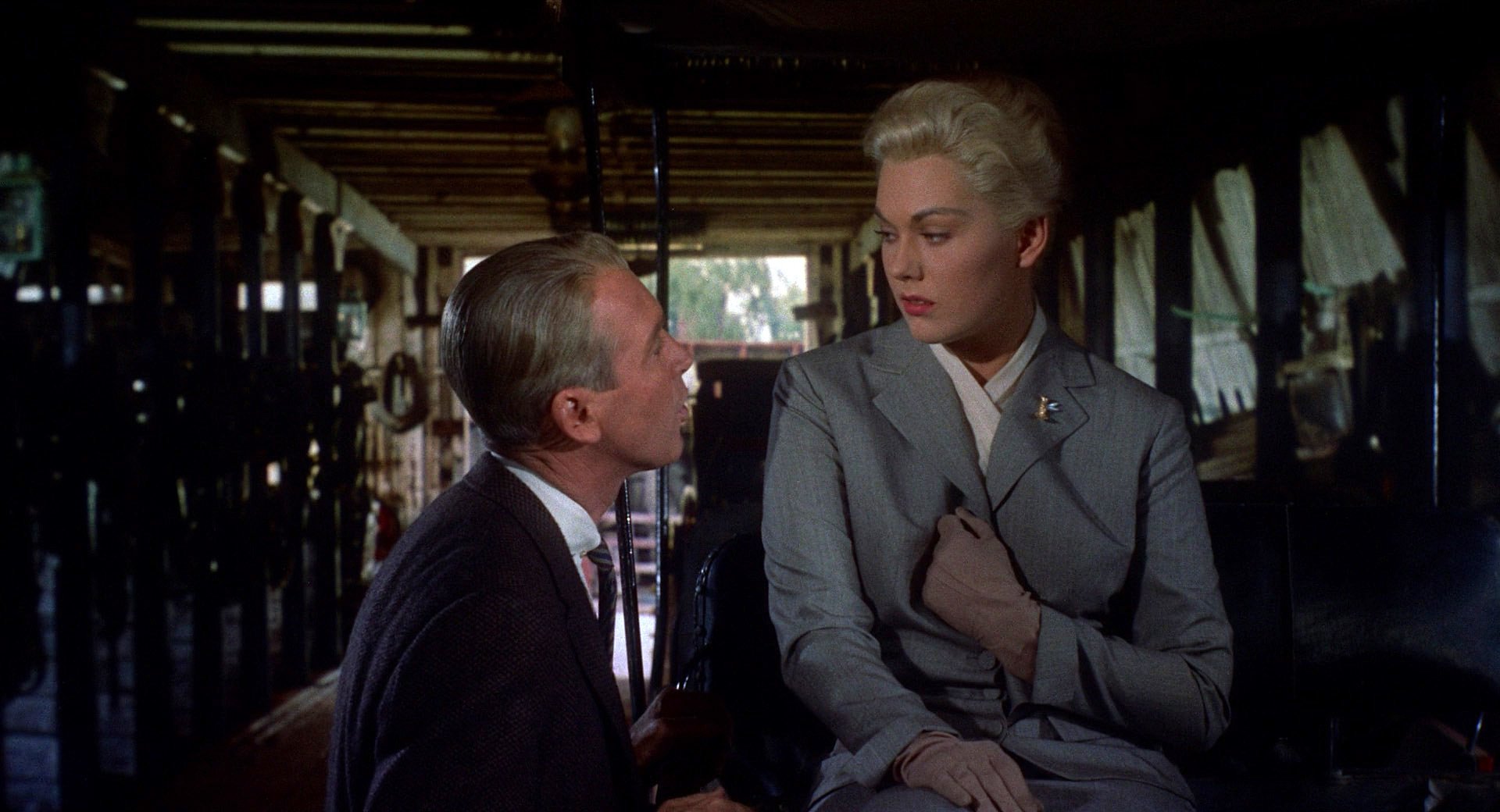

Hitchcock had developed a strong rapport with cinematographer Robert Burks, ASC, who had worked with him on eight films since 1951, and Burks’ camera operator, Leonard J. South, ASC, whom the director had known since The Paradine Case in 1947. They were making tests for Vertigo at the studio and on location as early as October 1956. Hitchcock supervised many of these tests, while others were directed by associate producer Herbert Coleman or assistant director Daniel McCauley. Principal photography commenced officially in September of 1957.

Vertigo was photographed in the VistaVision process, which was developed at Paramount as an alternative to such anamorphic formats as CinemaScope. The original VV cameras, made by Mitchell, exposed an 8-perf horizontal frame on 35mm film which traveled horizontally via an adaptation of the Mitchell intermittent movement. Single-mounted lenses provided focal lengths from 21mm to 152mm. The 2,000-ft. magazines were equipped with drive motors. The frame was 1.485” x 0.991” with an aspect ratio of 1.96:1; ratios from 1.33:1 to 2:1 could be extracted from this. For its own productions, Paramount chose 1.85:1, which conformed to the “golden ratio” preferred by many artists and cinematographers, and allowed plenty of headroom and a much sharper picture than CinemaScope could produce.

VistaVision was first used for White Christmas, which Paramount unveiled on a 30' x 55' screen at Radio City Music Hall on April 27, 1954. The VV logo carried the line “Motion Picture High Fidelity.” While some key city theaters ran the format horizontally, a printed-down 35mm version was used in smaller theaters. Even in this form there was a noticeable improvement in image clarity. At least 79 VV pictures were made in America and abroad before Paramount retired the process in 1961, though it is still used widely in visual effects work.

Hitchcock and Burks first used VV on To Catch a Thief (1955), for which Burks earned an Academy Award, and then on The Trouble with Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much (both 1955), Vertigo and North by Northwest (1959).

Most Vertigo exteriors were photographed on location in San Francisco — at Mission San Juan Bautista (founded in 1797) near San Juan; Cypress Point; Muir Woods National Monument in Marin County; and Big Basin Redwoods State Park, north of Santa Cruz.

Much of the photography involved doubles for Stewart and Novak driving their cars or walking with their backs to the camera. These were shot by second units usually directed by Coleman or McCauley and photographed by William N. Williams, ASC, Wallace Kelley, ASC or Irmin Roberts, ASC. The majority of scenes utilized 50mm lenses, with occasional use of 40mm and 35mm.

Most of the many plates to be used on the rear projection stage by Farciot Edouart, ASC and Kelley, and for optical compositing by Paul Lerpae, ASC, were also made by these cinematographers. Photographic effects chief John P. Fulton, ASC directed scenes for his department.

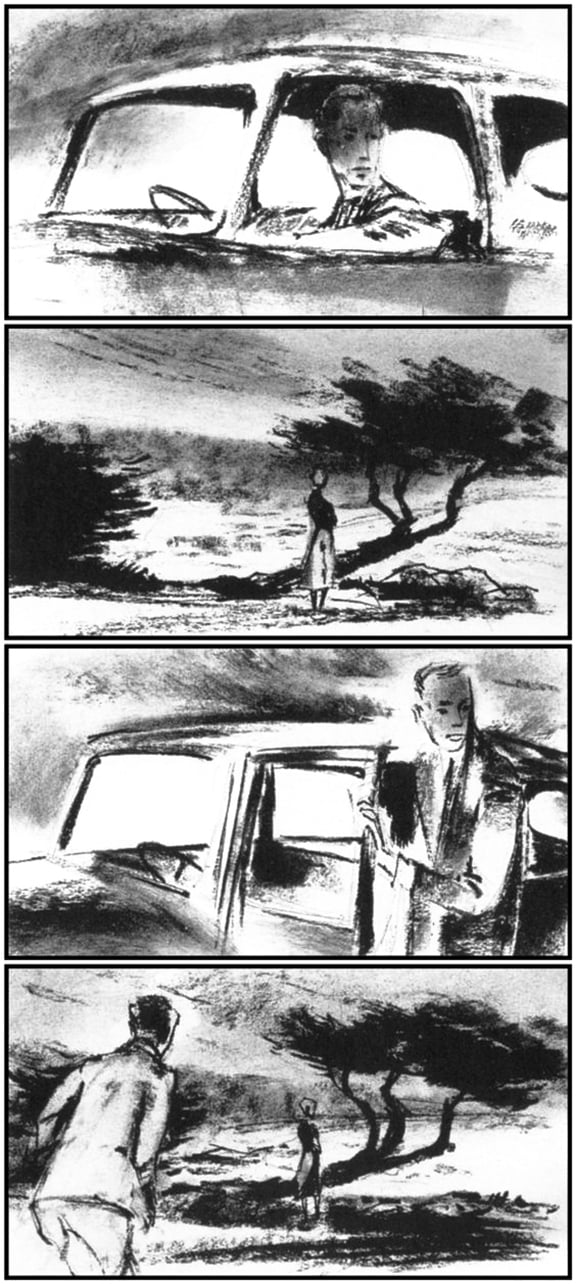

Vertigo’s justly famous titles sequence by Saul Bass open the movie. The camera moves in on a woman’s face — first to her lips, then to her eyes as they glance left and right, and finally to the pupil of her left eye. From the eye a dozen multicolored spiral patterns emerge slowly, one by one, and float toward the camera and out:

This sequence is accompanied by hauntingly lethargic music by Bernard Herrmann, which quickens as we see a chase at desk across downtown San Francisco rooftops. A suspect leaps across an alley to a steep roof and scrambles to safety. A policeman (Fred Graham) also makes it, but Detective Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) slips and nearly falls, hanging onto a rain gutter. The policeman, reaching to help, tumbles to his death:

The rooftop chase was shot by Burks on August 26 in downtown San Francisco with Coleman directing. The pair had been working since early morning filming street scenes of Madeleine’s Jaguar and Scottie’s DeSoto, both driven by doubles. At 4 p.m. they set up at the rooftop location, with Coit Tower and the Golden Gate Bridge in the background, and waited for the “magic hour.” Between 7:50 and 8:05 p.m., as dusk was falling and the city lights were coming on, they made four shots at different light levels. The last take, undercranked at 20 fps, proved excellent. The chase was augmented with scenes made on rooftops of the Directors Building at Paramount and Security First National Bank at Hollywood and Highland Blvds. The close shots with Stewart and the others were made much later on the process stage by Fulton, a veteran of seven Hitchcock pictures.

Scottie’s first seizure of vertigo, occurring just before the policeman falls, is dramatized by his POV: a shot aimed down toward the alley. In mid-shot the distance seems to stretch and the perspective distorts. The vertiginous effect was done in camera, utilizing a zoom lens and combining a forward zoom with a backward dolly move.

The policemen’s fall is also seen from Scottie’s POV, looking down toward the distant alley as the flailing body becomes smaller and smaller. Graham, a top stuntman and serial heavy, did the fall himself and was photographed from above as he fell some 40 feet onto safety padding. Positive and negative traveling mattes were used to print his body into the scene, creating the effect of the policeman plummeting to the pavement. Following a cut of Scottie staring down in horror, we see his view of people gathering around the crushed body.

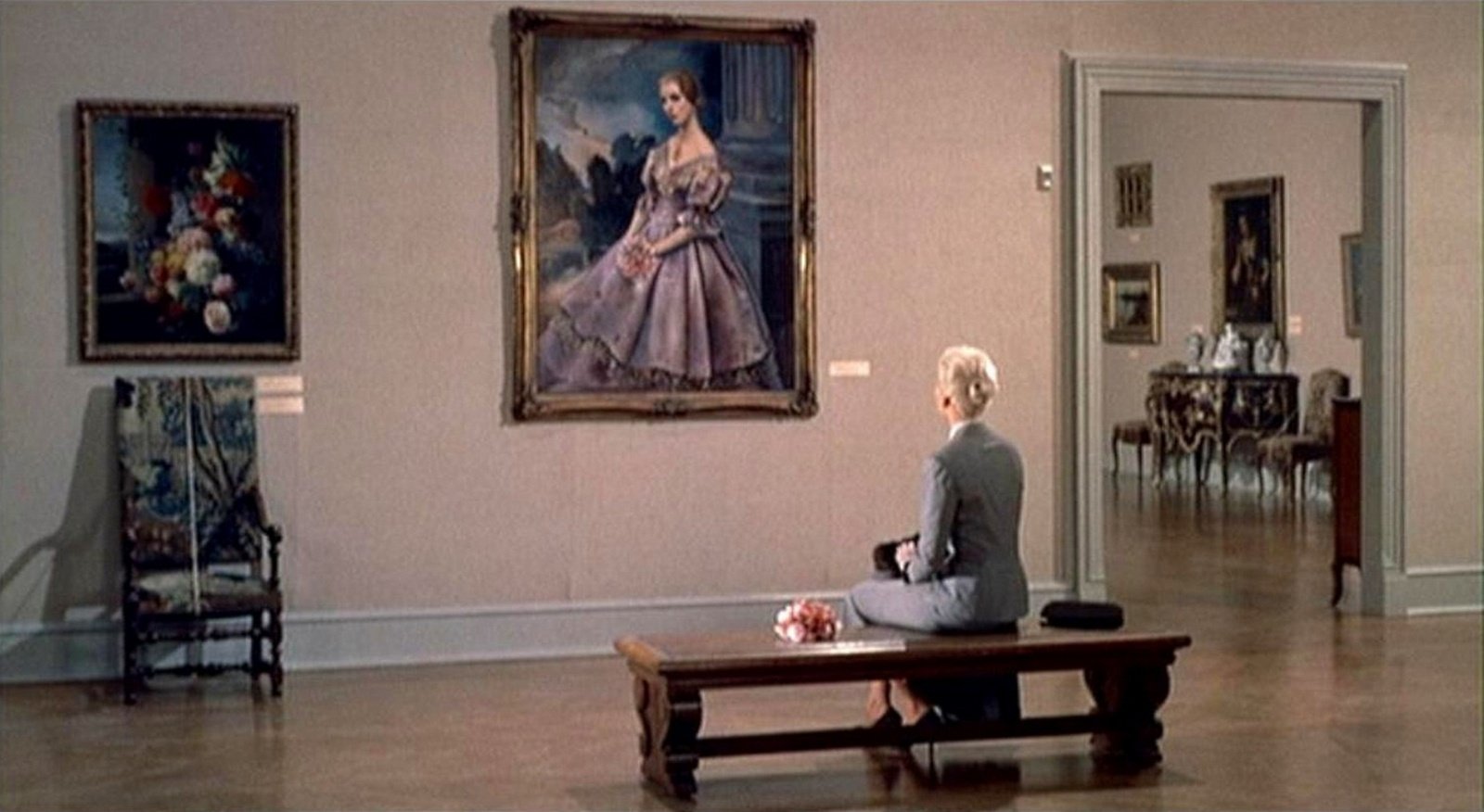

Now afflicted with acrophobia, Scottie quits the force. Some time later, Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore), an old college chum, hires him to trail his 26-year-old wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), an elegant blonde who wanders incessantly. He believes she has been possessed by the spirit of her great-grandmother, Carlotta Valdez, who committed suicide at the age of 26 in 1857. Scottie observes Madeleine taking flowers to Carlotta’s grave at Mission Dolores:

Scotty then watches as Madeleine sits and contemplates a portrait of Carlotta in the Palace of the Legion of Honor museum, and notes that she imitates Carlotta’s hairstyle:

Registered as Carlotta Valdez, she maintains a room at the rundown McKittrick Hotel, once the Valdez home. At the old Fort Point, under the Golden Gate Bridge, Madeleine leaps into the bay and is rescued by Scottie.

She awakens in his bed as he is drying her clothes. Scottie and Madeleine later begin to wander together, eventually going to Mission San Juan Bautista, 100 miles south of San Francisco. She insists upon going to the top of the bell tower. Following partway, Scottie is overcome with vertigo, hears a scream and sees her falling past a window. At the coroner’s inquest he testifies that Madeleine committed suicide. Elster leaves for Europe to try to forget the tragedy. Crushed by guilt, Scottie has a nervous breakdown.

Most of Vertigo’s exteriors were photographed on location. Rain, fog and overcast skies plagued the company in San Francisco and other locations, putting the picture increasingly behind schedule. Many day exterior scenes were shot in clear weather by using varying fog filters. Meanwhile, special diffusion filters were devised by Burks to lend Madeleine a magical greenish glow for certain scenes.

The actual San Juan Bautista Mission and its grounds were used in filming the exteriors. The building, which dated from 1812, had lost its tower in a fire, so John Fulton had it restored via matte paintings. One of these, a God’s-eye view looking down from above the tower to the sanctuary roof and the body, makes dramatic use of a dizzying perspective:

Another use of the vertigo technique depicts Scottie’s POV as he climbs the stairway in the tower. Hitchcock was told that the massive rig necessary to suspend and operate the equipment at the top of the full-size set would cost $50,000. Instead, the set was duplicated as a scale model and the zoom-dolly effect was filmed with the model lying on its side. The total cost was $1,900.

Polly Burson was the stunt artist who doubled Novak’s falls on the soundstage tower set. For the scene in which Madeleine apparently jumps from the mission tower, Burson fell 50 feet, turning and twisting, into a big circus net purchased recently from the Ringling Bros. She repeated the fall twice more in order to provide enough footage to use for a much longer fall, but in the final cut she is only shown falling headlong past a window.

The interiors, designed by Henry Bumstead, were built on soundstages at Paramount. The tower stairwell, 70 feet high, was constructed on the huge Stage 5, as were an Elizabeth Arden beauty salon, Scottie’s apartment, Elster’s office and Ernie’s Restaurant. Seven other stages held the coroner’s inquest room, the Fairmont ballroom, Midge’s apartment, sanitarium interiors, scale model steps, a Ft. Scott “exterior” with water tower, the Argosy Bookstore, Ransohoff’s dress salon, and the “exterior” of Scottie’s apartment. Process setups were done in Edouart’s Transparency Stage.

Scottie’s breakdown is symbolized by nightmare sequence designed by John Ferren: colors change, Madeleine’s flowers become garish drawings, and Elster embraces Carlotta Valdez at the inquest, after which she smiles at Scottie and sends him walking down a dark corridor that ends at an open grave in the churchyard.

Hitchcock makes his trademark appearance walking past Elster’s shipyard.

After suffering his nervous breakdown, Scottie is nursed back to health by his former fiancée, Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes). Months later he meets Judy Barton, a clerk who closely resembles Madeleine.

Obsessed with the idea of re-creating Madeleine, Scottie remakes Judy in her image. Conscience-stricken, Judy re-lives in her mind how, in the role of Madeleine, she lured Scottie to the church tower to witness the real Madeleine’s “suicide.”

In reality, Elster had broken his wife’s neck and dropped her from the tower. Scottie learns the truth when Judy wears one of Madeleine’s necklaces:

Crazed with rage, he takes her to San Bautista and, overcoming his vertigo, drags her to the belfry. Judy, who has fallen in love with Scottie, admits the truth. Suddenly a dark figure emerges from the stairwell. It is only a nun, but Judy recoils in terror — and falls to her death. In the last scene, Scottie stares down from the tower in desolation.

A coda was filmed, but not used: Scottie and Midge, having drinks in her studio, hear a radio announcement that Gavin Elster has been arrested in Switzerland.

One remarkable scene shows Scottie and Judy kissing as the walls to her room appear to turn and change into the inside of the stable at the mission, where he had kissed Madeleine. This was achieved by building a circular set using elements of the hotel room and the stable. The camera panned the set completely. This shot was projected behind the actors, who were placed on a turntable and then rotated to follow the movement of the projected image:

Polly Burson also doubled Novak for the tower flashback, in which the body is shown hurtling away from the camera toward the sanctuary roof. This was accomplished via a technique similar to what Hitchcock and Fulton had devised for Norman Lloyd’s fall from the State of Liberty in Saboteur (1942). A steel body frame extending from shoulder blades to lower back was made from a plaster body cast of the actress. This was fitted under her clothes and mounted on a black pipe eight feet long in a room covered in black velvet. She was photographed from above as she fell and the device was manipulated mechanically to turn her various ways, including head down. An optical pullback made the body become smaller as it fell. This was printed by the traveling matte process over a high shot supposedly made from the tower. Burson recalled, ironically enough, that she suffered vertigo through a full day’s filming.

Principal photography wrapped in time for the Christmas holidays. For understandable reasons, production had gone a long way past the projected 50-day schedule (including 10 days for preproduction and second unit), and vastly over the initial budget.

An integral part of Vertigo is the fine musical score by Bernard Herrmann, with its eerie use of Spanish motifs and romantic-tragic hints of Wagner. The scoring was as troubled as the rest of the production. Herrmann was unable to conduct his music in the U.S. because of a musician’s strike. He took the picture to London, where an English conductor was demanded. Muir Mathieson, England’s prestigious movie maestro, began the scoring sessions. Two days later the musicians quit in sympathy with the American union. Mathieson completed scoring in Vienna.

Vertigo was too puzzling and too downbeat to be generally popular at first look, but it has long since gained stature as one of the great romantic fantasies of the screen. Stewart is magnificent in his portrayal of a man on the edge of sanity. Novak offers the performance of her career in the very difficult role of a femme fatale who somehow gains one’s sympathy. Barbara Bel Geddes is poignantly touching as the kind of intelligent and loving young woman every man in trouble should have at his side. The atmosphere of real places and created settings, crisp editing, inspired music and imaginative cinematography made it possible to bring Hitchcock’s hopes and fears to life.

In the mid-1990s, major restoration on Vertigo was undertaken by industry veterans Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz, proprieters of The Film Preserve Ltd. The same team was instrumental in restoring Lawrence of Arabia, Spartacus and My Fair Lady. YCM Laboratories, Technicolor and Pacific Title also contributed their skills to what may have been the most elaborate photochemical film restoration to date. “Our ethic is to do it right or don't do it,” Harris comments.“We want to feel feel that Hitchcock would be happy with what we have done.”

Katz adds that “between Lawrence and My Fair Lady we had every problem one could possibly have, so we knew what we were getting into — and, for some reason, even that didn't stop us.”

An abundance of problems surfaced on Vertigo, the new prints of which were made on 70mm, with the picture's VistaVision images presented full-frame and pillar-boxed. Production photography on the original VistaVision negatives was fully exposed and had faded somewhat, but less than the other elements. The special effects scenes, which were composited using duping stocks that have faded badly, were “basically gone,” according to Harris, and had to be reconstructed. Also seriously faded were many of the heavily filtered San Francisco “fog” scenes — notably the graveyard sequence — and numerous chunks of dupe negative footage that had been cut in over the years.

Vertigo was originally released with a monaural soundtrack, however an original three-track stereo version exists and has been retooled into six-track digital stereo for the new prints. Part of the Bernard Herrmann score had been recorded in stereo in England and mastered on one kind of film, while the rest had been recorded in mono in Vienna on a different stock. Both had become “vinegary” and, as Harris notes, “Even the vinegars are different.” Worse yet, some of the score recordings had been junked in 1967. In spite of these obstacles, the Herrmann score was successfully reconstructed for 70mm presentation in DTS digital stereo — a first for the arena of restoration.

The sound effects tracks were in such poor condition that it was necessary to redo much of them with new effects, which included extensive foley work. “We tried to use all of the techniques we had without destroying the original aesthetics of the movie,” Katz says.

Vertigo was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.