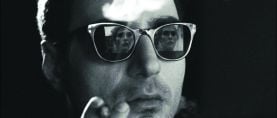

In Memoriam: Peter Sova, ASC (1944–2020)

The acclaimed director of photography died on August 27 at his home in South Kortright, New York, at the age of 75.

Born in September 25, 1944, in what is now the Czech Republic, Milan Peter Sova dreamed of attending film school in Prague, but his family was labeled anti-Communist, which created multiple difficulties for them. He abandoned his hope of becoming a filmmaker, training as a machinist instead.

Sova and his brother made plans to leave the country in 1966. No one knew that Alexander Dubček and the Prague Spring were around the corner. “I knew if I didn’t go with him, I’d never be able to escape because [the authorities] would keep such a close eye on me,” he told AC contributor David Heuring. “We found someone who could make counterfeit visas, and we started learning English. When we realized our guy was better at making Austrian visas, we dropped our English studies and started catching up on German!”

After Dubček came to power, Sova was able to obtain a visa to travel from Austria to the United States. His skill as a machinist enabled him to easily find work in Vienna and New York. During his first week in New York, among the five offers he considered was one from General Camera. He took the job and was soon converting Mitchell BNC cameras with rackover viewfinders to reflex. Each camera was a two-month job. He was in his mid-20s.

“The Czech trade schools were really good — the communists had taught me precision, fortunately,” he said. “But taking apart the Mitchell was scary. There were so many different parts. You had to make it run quietly, which was difficult. If the gears weren’t exactly right, then it would be noisy.”

On weekends, he could borrow cameras, and ABC gave him free 35mm film stock because he was fixing the network’s cameras. Developing the film could also be arranged. “You could learn a lot just from shooting on the Bowery in those days,” Sova recalled. “I watched the film and began learning to see the light.”

Eventually, he moved on to repairing cameras, and some of these jobs took him to sets. One director asked him to go along to New Hampshire on a shoot in case anything went wrong. On the job, he became the focus puller for cinematographer Vilis Lapenieks, who was known in Hollywood as “Crazy Vili,” according to Sova.

He soon earned his first credit as a cinematographer, a short for public television titled The Jolly Corner. Later, he shot the award-winning indie feature Short Eyes (1977), directed by Robert M. Young.

This adaptation of Miguel Pinero's play was shot in the Manhattan Detention Complex, a notorious detention center in Lower Manhattan also known as “The Tombs.” The cast included real inmates who had performed the play.

“There was sometimes, I would say, a little tension in there,” described Sova. “Somehow they were getting guns and heroin inside. But they were always nice to me — they liked that I was a refugee.”

Short Eyes earned Best Picture honors at the 1977 New York Film Festival, and also won the Best Cinematography prize at the Virgin Islands Film Festival.

Sova also shot many of director Barry Levinson’s features, including Diner, Good Morning Vietnam, Tin Men and Jimmy Hollywood, as well as director Mike Newell’s memorable crime drama Donnie Brasco.

While working with filmmaker Erroll Morris, Sova helped develop the Interrotron, a teleprompter-like interviewing device created to allow the subject to make direct eye contact with the camera while seeing a video image of the interviewer. It was first used on the 1997 documentary Fast, Cheap & Out of Control.

Frequently collaborating with Scottish director Paul McGuigan, Sova was the cinematographer on his features Gangster #1, The Reckoning, Wicker Park, Lucky Number Slevin and Push, which became his final narrative assignment.

Set in the Middle Ages, The Reckoning (2002) was filmed mostly in the U.K. and Spain. “In the north of England, the light is always soft, and the light in Spain is totally different, so moving from one to the other was a demanding change,” said Sova. “That was my greatest challenge. I got the biggest crane we could get in Spain, and I asked production to order a custom 80-by-80-foot double net. By putting that on a 150-foot crane, you can cover a lot of area. Because it was the Middle Ages, there were fires and smoke everywhere you looked. I had the effects team put little tubes through the net, so even the net was smoking. If the net ripped a little, even better, because we’d get shafts of light through it.

“I think for that day, it was the largest set in the world. It was a very difficult shoot, but the movie is pretty good.”

Shooting the twisty gangster tale, Lucky Number Slevin (2006) in Montreal, Sova found it inspiring to again work with McGuigan as the director was thoroughly involved in designing the look of the project at hand. “Paul has tremendous knowledge about filmmaking and a terrific visual sense,” he described. “He did a lot of fashion photography before he started directing, and he has strong ideas about cameras, costumes and production design. When we first met, we established that we had similar thoughts about the way a camera should move to complement a scene, and by now we have a shorthand; each of us knows what the other will think of an idea.”

“Push was incredibly demanding,” Sova said of the Hong Kong shoot for McGuigan’s 2009 sci-fi thriller. “That was one of the reasons I stepped aside. I had something like 28 electricians, and only one or two spoke English. The weather forecasts said a typhoon would come, so we were working seven nights a week, 14 hours a night. When you do this for two weeks, you just collapse — at least, I do! If I were 28 years old, it would be different. Movies and producers have changed from the days when I shot Diner. There’s so much pressure now. And in Hong Kong, there are no rules like there are in Hollywood.

“I did it because [director] Paul McGuigan, with whom I’d made four films, asked me to,” Sova continued. “But when it was finished, my wife was ill, and I wasn’t even thinking about movies. I decided it was time to stay home with her and our new dog, a chocolate Lab.”

His final project was the documentary Driven to Abstraction (2020).

Sova became a member of the ASC in 1999, and his other credits include the telefilms Summer of My German Soldier, Fatherland and A Doctor’s Story, the TV series The Equalizer and Thief, and the features The Proposition, Straight Talk, Sgt. Bilko, Late for Dinner, Close Your Eyes and The Strangers.

Sova’s wife, Elizabeth, passed in 2018, and he is survived by his son, Milan Joseph Sova.