In Memoriam: Ralph A. Woolsey, ASC (1914-2018)

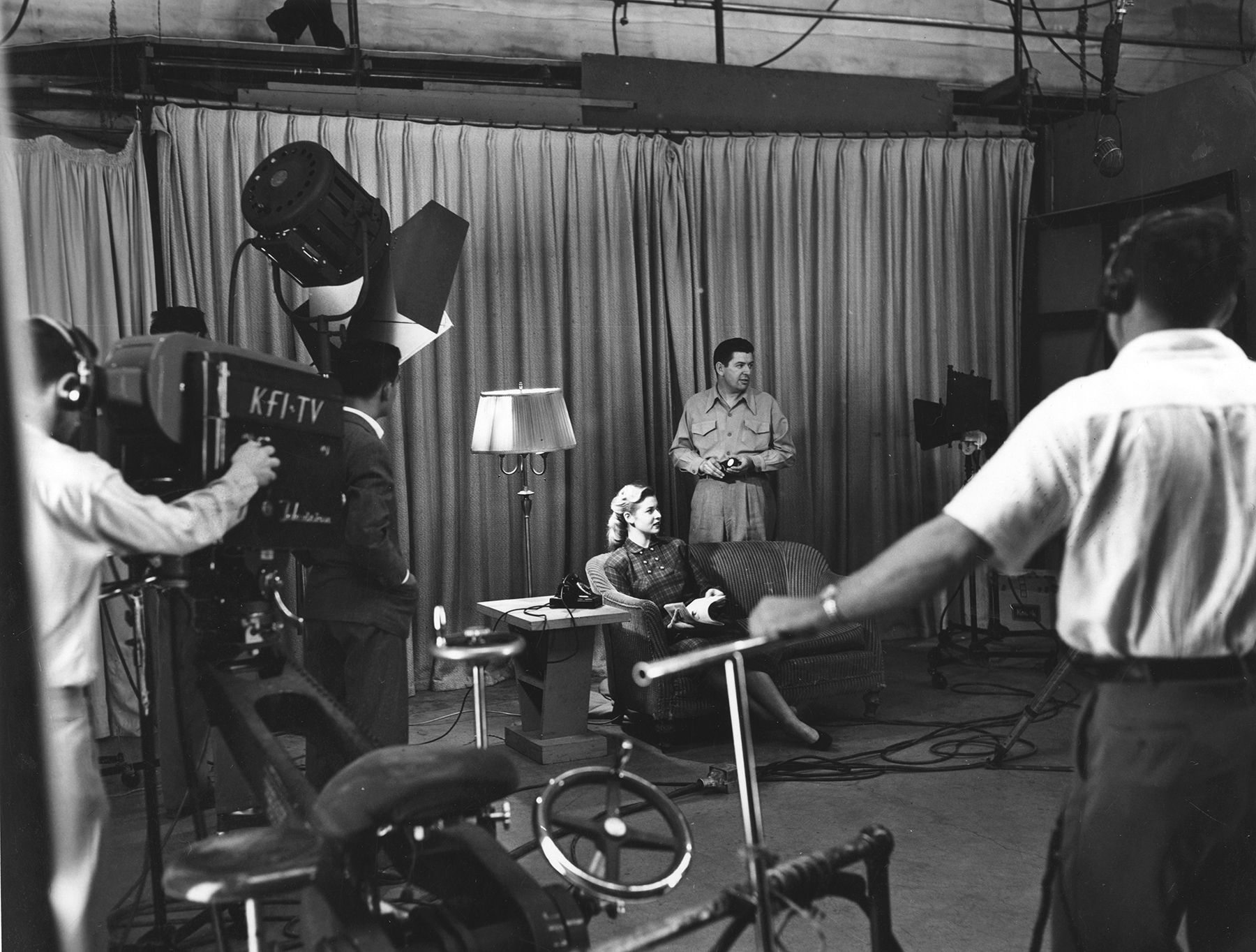

The Emmy-winning ASC great helped shape the look of television in the 1950s, and photographed such series at Maverick, 77 Sunset Strip and Batman.

Emmy-winning cinematographer Ralph A. Woolsey, who was the oldest living member of the ASC, died on March 23 at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, Calif., at the age of 104.

A consummate technician whose Hollywood career paralleled the birth and early evolution of television cinematography, including the transition from black-and-white to color, Woolsey shot such series as Maverick, 77 Sunset Strip, Batman and Mister Roberts.

Born in Oregon on Jan. 1, 1914, to an American father and a German mother, Woolsey was raised in the Pacific Northwest and in Shakopee, Minn. The first movies he saw were silent, and although Saturday westerns were a favorite, the budding piano student was more intrigued by the theater’s Wurlitzer organ than he was by the images on the screen. It was actually a love of bird watching and nature that inspired him to learn photography, which he took up in high school.

After graduating, he moved to Fargo, N.D., and spent several years working for Ford Motor Co. and moonlighting for a local photographer. He returned to Minneapolis and enrolled at the University of Minnesota, intent on becoming a zoologist. He later told American Cinematographer that he was also attracted by the school’s photo lab, which was “staffed by professionals who did every conceivable kind of photography.” Soon Woolsey was making conservation films for the state of Minnesota and industrials for Bell Aircraft; some of the latter were used to train U.S. Air Force during World War II.

Woolsey moved to Los Angeles after the war, landing jobs at Technicolor and at Photo Research Corp., where company founder Karl Freund, ASC, was developing specialized light meters. “Every meter was custom-calibrated based on a particular studio lab’s processing methods,” recalled Woolsey, who shot tests and delivered the meters to cinematographers. He connected with ASC members Leon Shamroy, Joe Walker and Arthur Miller, among others, and it was Miller who eventually proposed Woolsey for ASC membership. By the time Woolsey was invited to join the ASC, on Sept. 10, 1956, he was also an educator; Slavko Vorkapich recruited him to teach cinematography at the University of Southern California in 1950, and Woolsey did this for seven years, shooting small projects on the side.

In 1957, Woolsey got a call to fill in for a cinematographer who had fallen ill just as Warner Bros. was about to begin production on the new TV series Maverick, starring James Garner. With access to studio resources and seasoned crew for the first time, Woolsey jumped right in, and the craft and speed he had honed as a freelancer paid off immediately: a few days into the shoot, Warner Bros. offered him a five-year contract. In 1959, his camerawork in Maverick also brought him his first Emmy nomination.

In an extensive, wide-ranging conversation with The Classic TV History Blog about his career, which included shows at Warner Bros., Fox and Universal, Woolsey discussed the learning curve the new medium presented on studio lots. “[At first] we were using feature sets, which actually made some of the very first shows look fantastic. On the other hand, you paid a price because it took longer to work with those sets — they were more elaborate, took more lighting… And we had crews who had been working on pictures for years, so sometimes they would tend to be a little too fancy or elaborate for a television show. In other words, you had to say, ‘Forget the frosting on the cake, and let’s take care of the meat and potatoes first.’”

Woolsey received his second Emmy nomination in 1960, for 77 Sunset Strip, and he won an Emmy for the pilot It Takes A Thief in 1968.

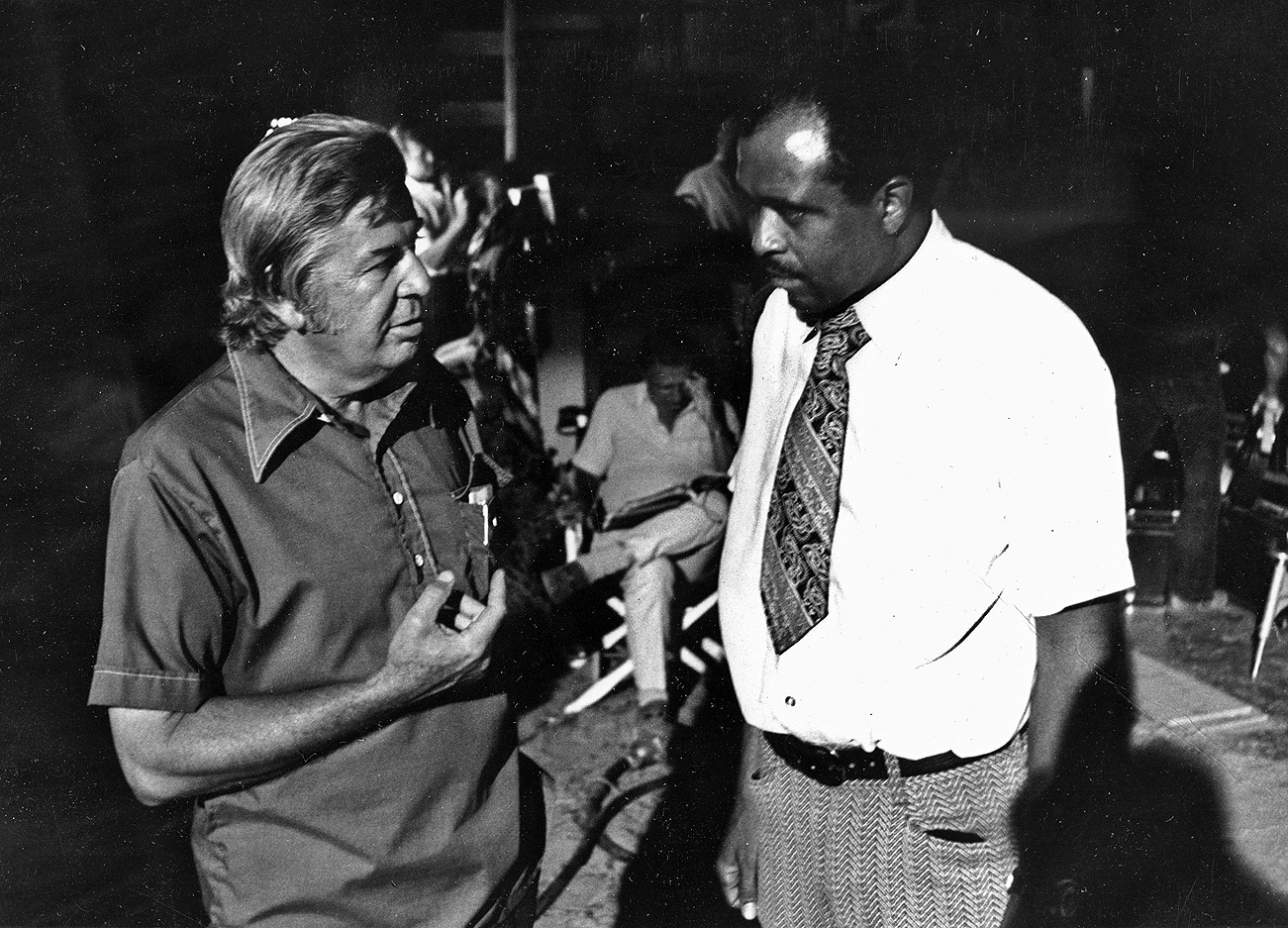

He transitioned to shooting features in the 1970s, and as his career flourished, he continued to teach when his schedule permitted. For an American Film Institute seminar in 1977, he discussed one of his more unusual features, a 1973 adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh directed by John Frankenheimer. (Excerpts from the seminar were published in AC in February and March ’78.)

Confronted with a four-hour dialogue-heavy drama that unfolds in one room over the course of a single night, Frankenheimer and Woolsey understood that wider angles and a variety of unobtrusive camera moves would be vital. “[We knew] we must never lose sight of the geography at any time,” the cinematographer said. “We also wanted to keep the camera setups interesting and keep repositioning the camera according to the way the play progressed.”

Woolsey used devices he dubbed “table scrapers” to slowly slide the Panavision PSR across the bar and tables — even, on a couple of occasions, moving “right up the middle of a banquet table, just missing the candlesticks.” Believing that an “antique look” suited the material, he also force-developed the negative (100 ASA Eastman 5254) to desaturate the color and add grain. “One reviewer said it had the look of shooting through watered whiskey,” he noted with pleasure.

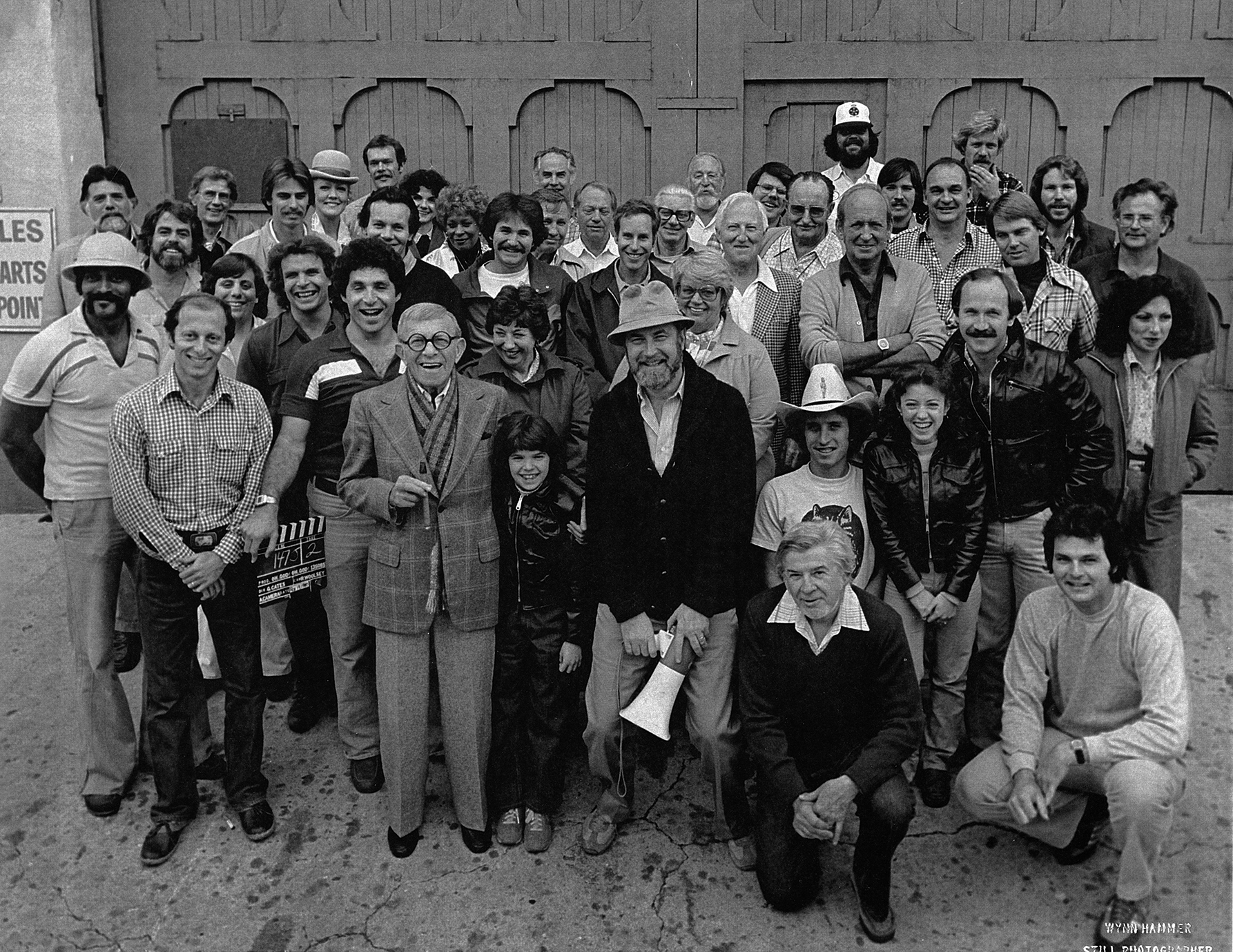

The cinematographer’s other feature credits include The Culpepper Cattle Co., The New Centurions, Mother, Jugs & Speed, The Mack, The Last Married Couple in America, Oh God! Book II and the memorable drama The Great Santini:

Woolsey served as the ASC President from 1983-’84. He was honored with the ASC Presidents Award in 2003 for his unique and enduring contributions to advancing the art of cinematography. (See AC Jan. 2003.)

“Ralph has earned the respect and admiration of peers for his innovative spirit and artistry as a cinematographer,” noted Owen Roizman, ASC, chairman of the ASC Awards Committee at the time. “This tribute also recognizes his dedication to advancing the art of filmmaking. Ralph has mentored hundreds of students at film schools, teaching the skills and aesthetics necessary for success.”

“Ralph Woolsey is a talented and unselfish artist who has taught many students and inspired countless colleagues, including myself, with his total dedication to his profession,” said then-ASC President Steven Poster. “He deserves this recognition, and it is our privilege to present it to him.”

In 2014, the ASC helped Woolsey celebrate his 100th birthday with a party at the ASC Clubhouse.

“People ask me my secret for longevity, but the truth is I don’t pay that much attention to that aspect of it,” Woolsey told AC contributor David Heuring. “I can’t move as quickly as I used to; that’s the main difference I’ve noticed. Having a lively interest in anything, particularly something that has been your life’s work, really helps."

Woolsey is survived by his sons James, Richard and Robert.

The following clip (and the image at the top of this page) is from a long-form interview with Woolsey conducted by filmmaker/cinematographer Artur Gubin: