In Memoriam: William Taylor, ASC (1944-2021)

The Emmy-winning and Academy-honored master of visual effects linked the analog and digital eras, bringing time-tested techniques and classical artistry into the modern age.

“The compelling fascination of my life has been visual illusion, both as entertainment in itself and in the service of storytelling, which turned out to be my career in movie visual effects,” William “Bill” Taylor, ASC explained with characteristic humility in an autobiography penned for a San Marino High School class of 1962 reunion. Honored for his work by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Television Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Visual Effects Society, he was an innovator and expert in his field.

Born on July 5, 1944, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Taylor died on August 28, 2021, at the age of 77

Interested in the arts from an early age, movies were just one inspiration. “As a pre-teen would-be artist, I loved the classic Disney animated movies, particularly Pinocchio [1940],” he told American Cinematographer in 2016. “For live-action, it was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea [1954], hands-down. When I was a young teen, I loved Ben-Hur [1959] — the past brought to life on an enormous scale.” But Taylor was not yet interested in becoming a filmmaker. Instead, he dreamed of being a stage magician, or building a career in radio.

Buying a Polaroid camera helped spark his interest in experimenting with photography as a means of creating illusions: “I could do split-screens and tricky perspective and see the image right away. That’s probably why I love digital imaging: no waiting!”

In 1961, Taylor’s family relocated to southern California, where he attended SMHS and he became very active in the drama department, both on stage and behind the scenes. “I saw a lot of movies as a kid, but the moviemaking bug didn’t bite until I was 19 and at Pomona College,” he said. “I saw Jason and the Argonauts [1963] on the big screen and was blown away. Ray Harryhausen’s miraculous combinations of animation and real actors seemed like magic on an enormous scale.”

Meanwhile, Taylor’s studies at Pomona as a philosophy major failed to maintain his interest: “My very brief college career sputtered to a halt after three semesters. It seemed unlikely I would set the world on fire as a magician or as a radio personality — I did college radio at Pomona — but the movie business seemed like a possibility.”

To that end, Taylor introduced himself to visual effects pioneer Linwood G. Dunn, ASC — himself a bit of a magician, at least with his optical printer. “Lin gave me some great job-hunting advice: ‘Take a job, any job, even if it’s carrying someone’s briefcase. Just get in.’”

In 1964, Taylor landed his first film gig, at Ray Mercer & Company, a Hollywood-based title and optical effects house with roots in the Silent Era. “I began as line-up tech — transcribing workprint information and preparing count sheets and film rolls for the optical-printer operators — and a part-time delivery driver,” he described. “At Mercer’s, a great optical cameraman named Jim Handschiegl taught me the basics of the bluescreen process. Petro Vlahos, the inventor of the Color Difference Traveling Matte system and the creator of Ultimatte, taught me the rest — starting with how to get rid of that pesky blue blur — in a couple of classes at the University of Southern California, and the friendship that followed continues to this day.”

He learned more about the bluescreen process by reading Ray Fielding articles in the SMPTE Journal.

Another key teacher in Taylor’s informal education process was Albert Whitlock, head of the matte department at Universal Studios and one of the finest practitioners of his craft. “I cold-called him after I saw some spectacular examples of his work in a middling Universal comedy, That Funny Feeling [1965],” Taylor explained to AC. “It was all shot on the backlot with the telltale reduced-scale buildings, but there are these beautiful matte-painting shots that put the characters in a very convincing Manhattan. The photographic quality was flawless; there was none of the dupe-y quality I saw in matte shots from other studios. I had to find out how that was done.

“[Whitlock] was willing to talk to a complete stranger about his work, and a few months later invited me to meet him at the studio.”

Mercer & Company got Taylor into the camera union, Local 659, in 1966 and moved him up to camera operator. “In that job, I shot optical effects, titles and product inserts on thousands of commercials, trailers, and feature films. The experience in thinking of images combined in layers was invaluable.”

Meanwhile, Taylor continued to look for ways to improve his craft, in part by better understanding how on-set cinematography affected what he could accomplish in post. As he told AC in 2019, “I eventually became an expert in doing bluescreen composites on the optical printer. I soon realized that one of the biggest problems with bluescreen composites at the time was the fact that they weren’t lit correctly. Foreground lighting wasn’t realistic — and, secondly, the relative brightness of the bluescreen was usually seriously underexposed. So it was a matter of ‘self-defense’ to figure out, by following Petro [Vlahos]’s lead, how to light realistically and expose bluescreen shots properly. I might have been the last cinematographer to carry shots all the way through from original photography to executing the composites.”

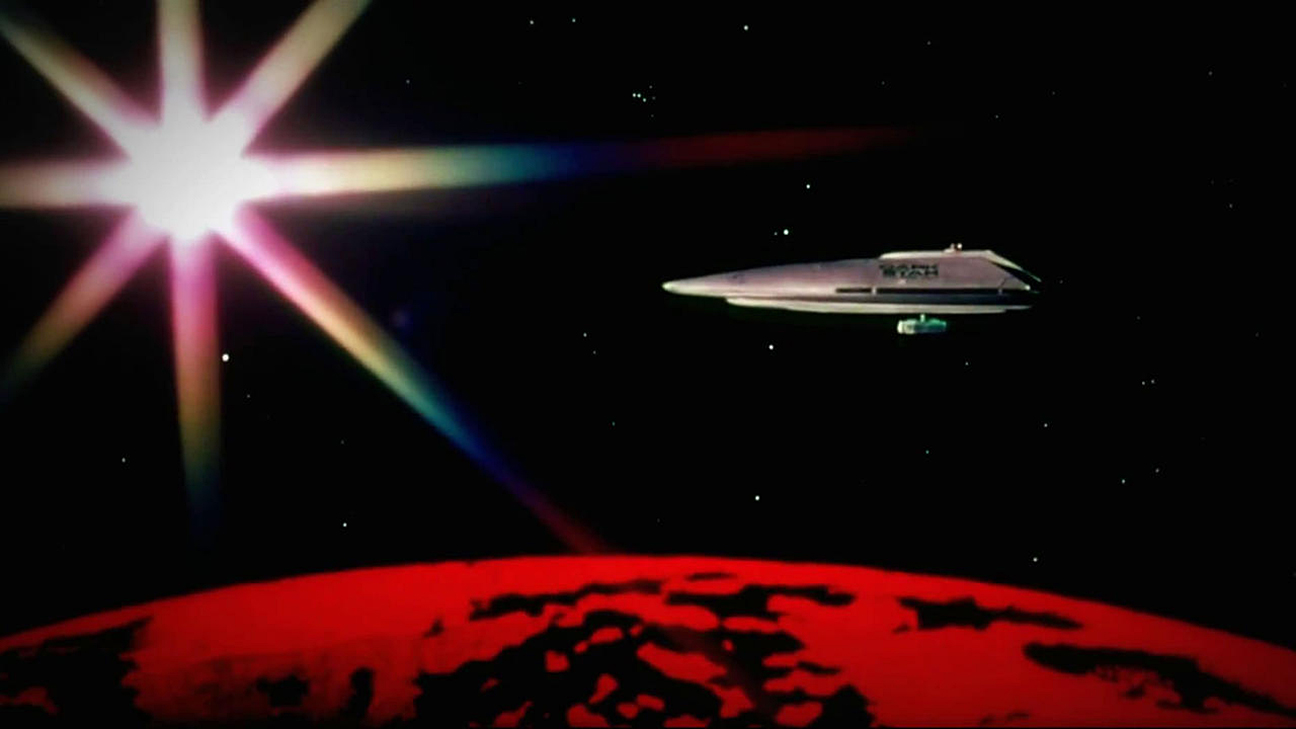

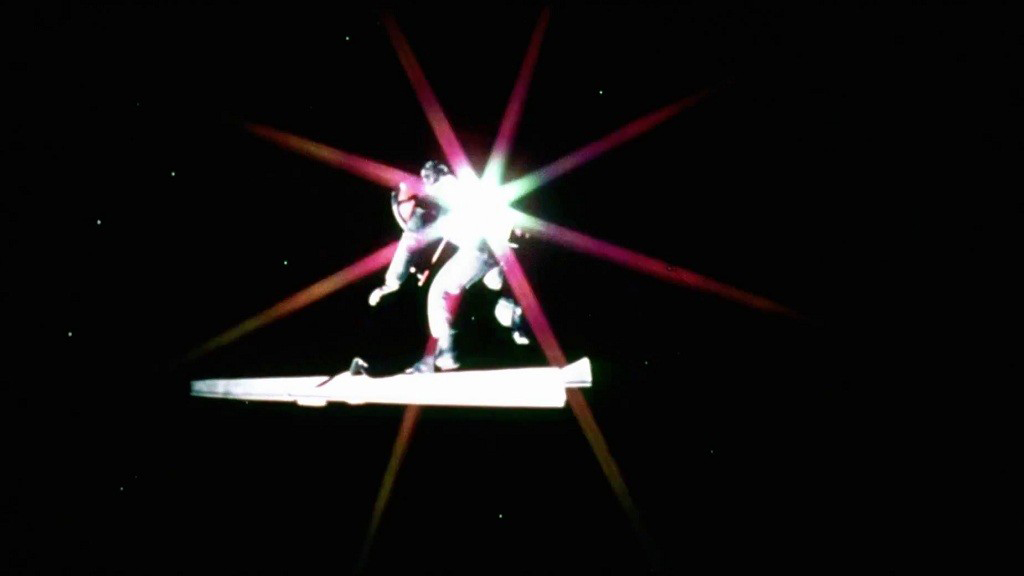

Another big break for Taylor was meeting an ambitious young USC student named John Carpenter, “who was shooting a film on my doorstep.” The 45-minute 16mm short thesis film was later expanded to become the cult-classic sci-fi feature Dark Star, featuring a blow-up to 35mm and visual and optical effects by Taylor, and later released theatrically in 1974. It was one of his first feature screen credits, and he “also wrote the lyrics for the country-western title song, ‘Benson Arizona.’”

Taylor would later appear in small acting roles in Carpenter’s subsequent features Assault on Precinct 13 and The Fog, as well as contribute effects work on his 1982 remake of The Thing.

After nine years at Mercer — working on non-studio features including Thunder Alley, The Reivers and Bigfoot — Taylor left for Rio de Janeiro in 1973 to supervise the effects work on a Brazilian feature that ended up folding in pre-production: “I returned to L.A., minus my equipment and without a job.”

Down but not out, Taylor freelanced at Lin Dunn’s company, Film Effects of Hollywood, alongside Don Hendricks and Cecil Love. Then, in 1974, he found a new opportunity: a full-time position at Universal, working for Al Whitlock. “That phone call changed my life,” Taylor said, referring to the cold call he’d made years before.

“Eleven years as a cameraman for Al Whitlock in the Universal Studios Matte Department taught me how to see,” Taylor said. “There’s no better way to learn the aesthetics of imagery than working around great artists like Al Whitlock and Syd Dutton, not to mention Al’s friends [production designers] Henry Bumstead, Bob Boyle and Harold Michelson.”

Whitlock’s influence included impressing Taylor with his love for fine art, which in part inspired his own work. “I love the English landscape painters — Constable and Turner particularly,” Taylor explained to AC. “They have everything to teach about composition and color. Turner’s last work leapt right into the 20th century, even though he died in 1851. Ansel Adams and Elliot Porter are the photographers who got to me first. I still think Adams’ Zone System is the best method of visualizing exposure, even in this digital age; Porter, whose meticulously composed — and rarely cropped — 4x5 color images still pack a wallop, was a master of pure craft.

“Thanks to Al, I learned photography, composition and perspective from an artist’s viewpoint, and began to comprehend his profound grasp of what made a shot convincing.”

The Universal matte department worked on an array of projects, starting with The Hindenberg, for which Whitlock and Glen Robinson won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. “Suddenly, I was in the big time,” Taylor said. “Universal promoted me to director of photography and I began to light and shoot many of the shots our department worked on.”

Over the years, they worked on more than 100 productions, including Swashbuckler, Airport ‘77, The Wiz, Dracula, MacArthur, Heartbeeps, Ghost Story, The Blues Brothers, Cat People, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, Blade Runner and Dune. “Whitlock was a magnet for distinguished filmmakers, and as a result we got to work on films directed by everyone from John Huston (The Man Who Would Be King, Under the Volcano), to Alfred Hitchcock (Frenzy, Family Plot) to Franklin Schaffner (Papillon).

This work led to numerous experiments and innovations. In 1982, during the Academy Scientific and Technical Awards, Taylor was honored with a Technical Achievement Award certificate for the concept and specifications for a Two Format, Rotating Head, Aerial Image Optical Printer. The device allowed for the use of VistaVision, ensuring optimal image quality.

Taylor then shared an Emmy Award win with Whitlock, Dutton, Mark Whitlock, Dennis Glouner and Lynn Ledgerwood for their visual effects work in the Biblical miniseries A.D. (1985).

Following Whitlock’s retirement of in 1984, Taylor and Dutton set up the independent effects studio Illusion Arts, Inc. — first operating at Universal and then occupying a studio in Van Nuys. “Universal became one of our best clients,” Taylor said. “We eventually got screen credit on nearly 200 films, with a wildly diverse bunch of directors: among them Martin Scorcese (Cape Fear, The Age of Innocence), John Landis (Coming to America, Innocent Blood), and Mike Nichols (The Birdcage).

Taylor later, served as on-set visual effects supervisor on The Fast and the Furious, Bruce Almighty and “my all-time favorite, Lasse Hallstrom’s Casanova, which sent me to Venice for six weeks. Later still, Syd and I co-supervised Milk, our sixth film with director Gus Van Sant, for which we created more than 150 ‘invisible’ shots. As Illusion Arts wound up its 26-year run, our company completed dozens of shots for Michael Mann’s Public Enemies for supervisor Robert Stadd, and some key environments for GI Joe.”

Taylor also did second-unit or model-unit cinematography for films including Daylight, Clockstoppers, Serenity, The Nanny Diaries, Rambo and Soul Men.

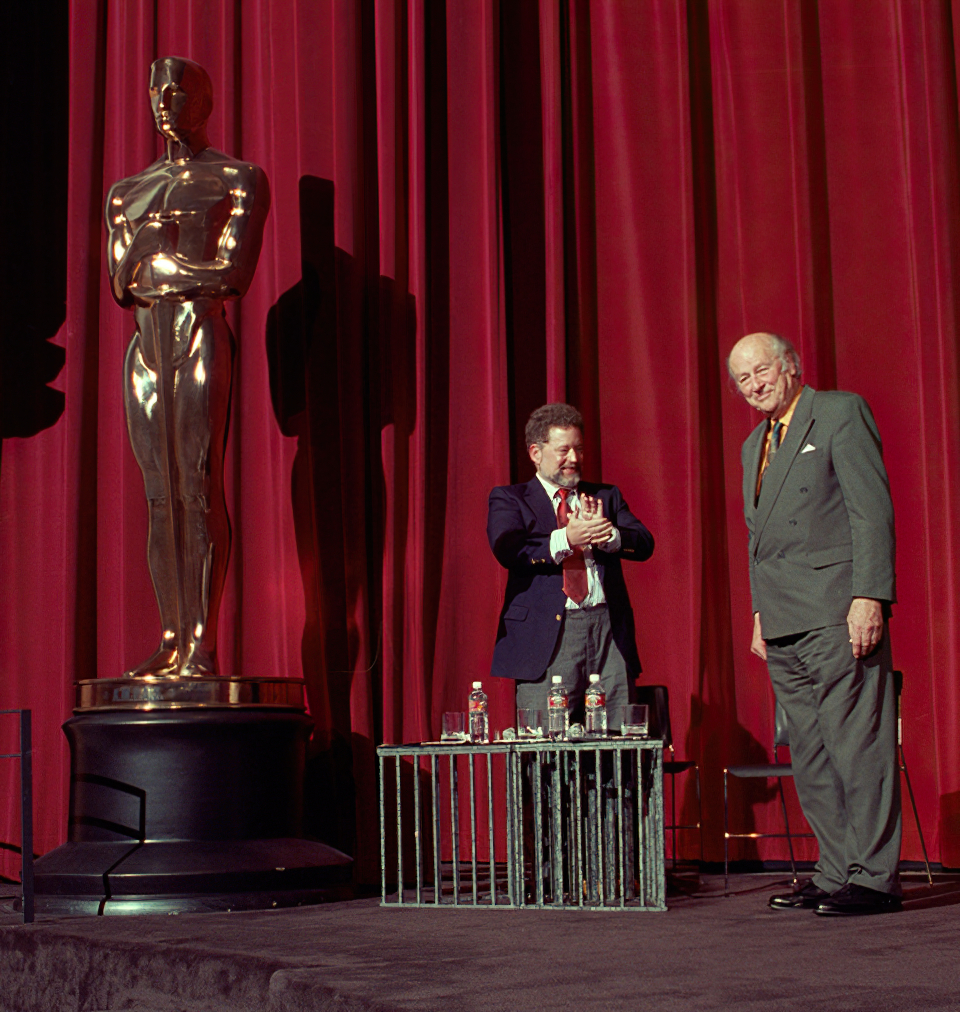

In 1972, Taylor became a member of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences: “Like any other mostly volunteer organization, the Academy can take as much of your time as you are willing to give.” He would go on to serve as a governor of the Visual Effects Branch for 19 years. He was a Nicholl Fellowship Volunteer Member Judge for 12 years, and also served on the Scientific and Technical Awards Committee for three decades. “Closing a couple of circles very nicely, I had the pleasure of presenting two Academy programs honoring my inspiration Ray Harryhausen, and a program honoring my mentor Petro Vlahos.”

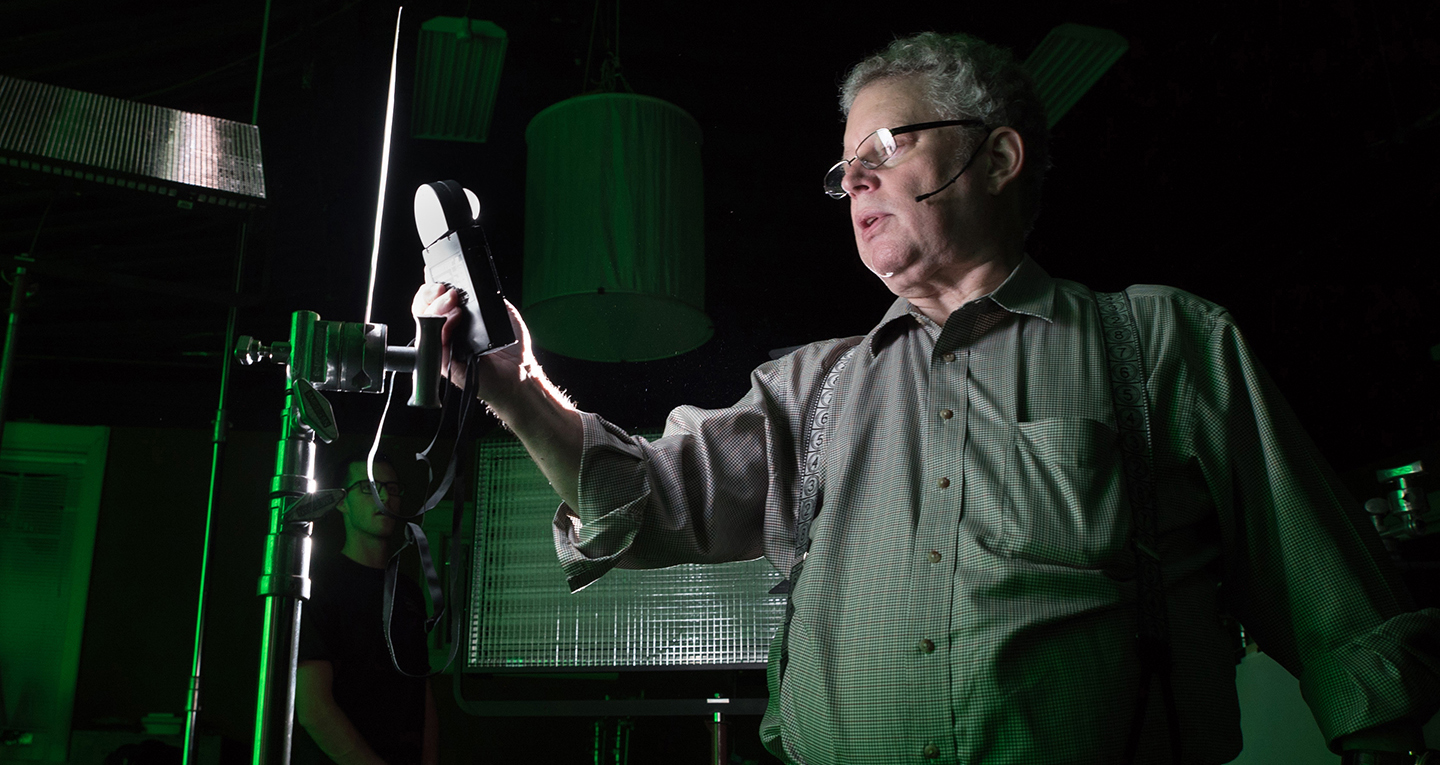

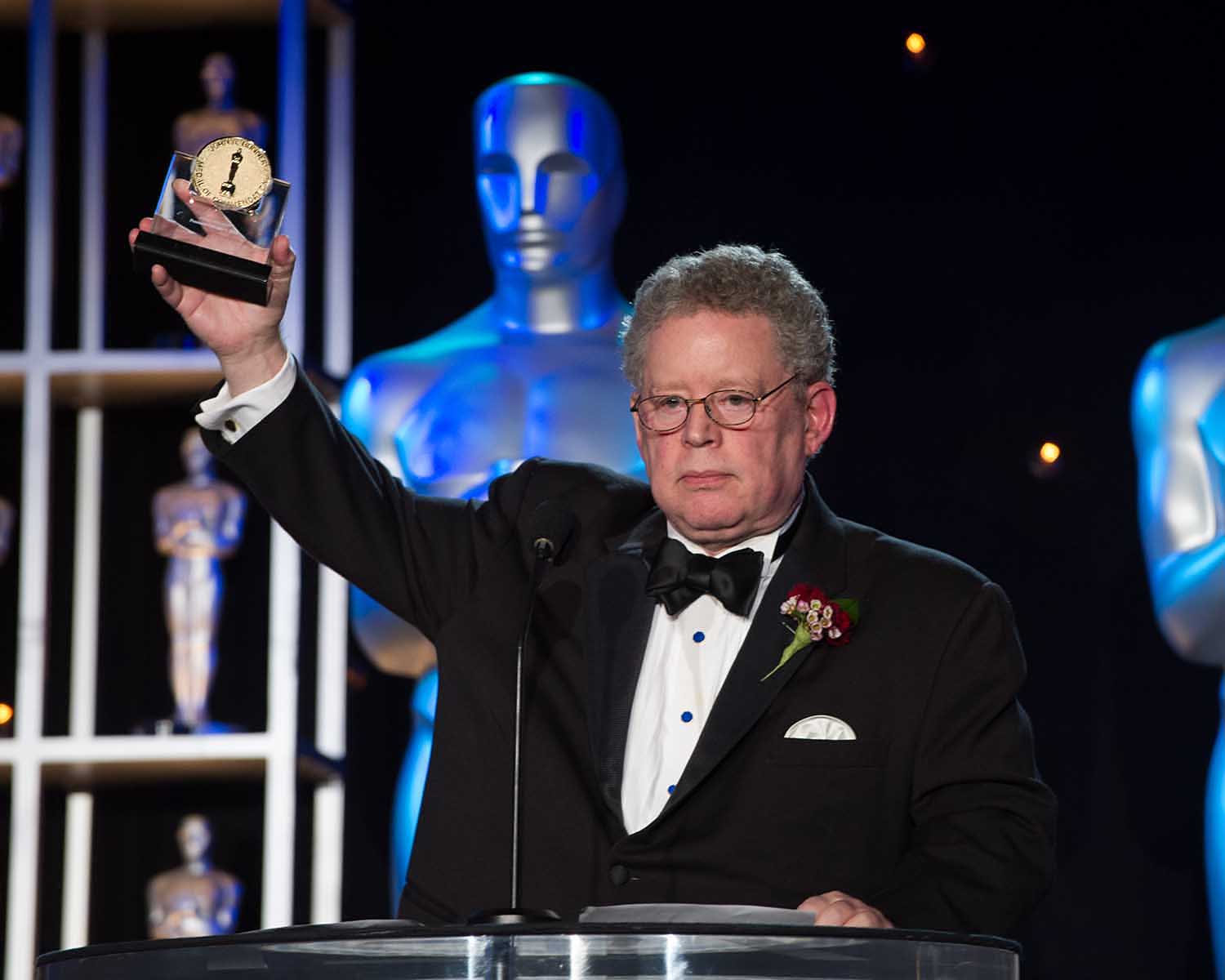

In 2013, Taylor (above) was honored with the John A. Bonner Medal of Commendation in appreciation for his outstanding service and dedication in upholding the high standards of the Academy.

Of note, following the closure of Illusion Arts, the company’s archive of material was donated to the Academy Film Archive, and consists of more than 3,200 items, including elements from virtually every effects shot created at IA.

In 1987, Taylor was invited to join the ASC as an active member, recommended by Richard Edlund and Joe Westheimer — both visual effects greats themselves — and Harry Wolf, then President of the ASC. “It was a great moment when I first saw my name onscreen with the letters ASC after it,” Taylor remembered. “Membership has been a conduit for my continuing education about movies and moviemaking techniques; I can find the answer to almost any question by consulting an ASC member, and I’ve had the honor of contributing to that tradition. I’ve also had the chance to meet so many of my heroes in a social context, discovering they are not only human, but also incredibly generous men and women. And I suspect that being an ASC member gives me a little more credibility when I first meet the team on a new film.”

The Television Academy honored Taylor and Dutton and their collaborators with two 1991 Emmy nominations for their work in episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

In the early 1990s, digital effects tools and techniques began to rapidly alter the art of visual effects and the business. “Over my career, the most important development I saw was digital compositing — a Kodak invention,” Taylor told AC. “They had a [team] at Kodak Australia that invented digital compositing from the ground up with their Cineon system [which was unveiled in 1992]. The second revolution was the advent of digital photography that was co-equal in quality with film photography. After those two big revolutions, visual effects began to appear in films of every type and genre.”

In 1997, Taylor became a founding member of the non-profit Visual Effects Society, serving as a member of the board for many years. He was later honored as a VES Fellow, a Lifetime VES Member and was then a recipient of the VES Founders Award.

Looking at his Hollywood career in terms of film history, Taylor noted, “I feel lucky to have been at this vantage point to see all the important scientific and technological developments in motion pictures. And that illustrates one of the important intersections between cinematography and visual effects: We in the visual-effects field have been able to give first-unit cinematographers a new toolset that they can bring to bear to overcome photographic storytelling challenges.

“You learn so much by watching a great cinematographers work, and as a visual-effects supervisor, I had the priceless experience of working with many of the greats, including ASC members Sven Nykvist, Vilmos Zsigmond, Haskell Wexler, Vic Kemper, Dean Semler, Chivo Lubezki, Roger Deakins, Peter Deming and Walter Lindenlaub, and BSC members Jack Cardiff, Oliver Stapleton and Freddie Francis. I regret I wasn’t able to work with Owen Roizman, ASC before he retired.”

Taylor freely shared his invaluable experience and insight, co-authoring with Petro Vlahos chapters on bluescreen and greenscreen compositing in both the American Cinematographer Manual and the Visual Effects Society Handbook. He was also a frequent instructor in the ASC Master Class program, during which he would detail his approach to lighting for visual effects. “He turned my extensive experience of working with greenscreen on its head,” said veteran gaffer, cinematographer and student David McGrory about a seminar taught “by the amazing Bill Taylor. His techniques were unlike anything I had seen before, even after lighting multiple Marvel films.”

While Taylor never fully pursued his childhood dream of being a professional stage magician, the slight-of-hand arts remained a part of his life, and he worked behind the scenes creating large- and small-scale illusions for performers including Harry Blackstone Jr., Doug Henning, The Great Tihany, The Fercos Brothers, The Pendragons, The Gamesters, Harry Anderson, and many others.

“My best-known illusion is a giant version of the classic three-shell swindle called ‘Trash Can Monte,’” he described. “In performance, the audience can’t quite follow under which can a beautiful woman is hiding. In the climax to the effect, three different women appear unexpectedly. A promo photo for this might be the funniest of my life.”

Taylor’s creative interests in design and photography extended far beyond the movie business. “My photos illustrate books on sleight of hand, magic performance, and the allied arts by John Carney, Earl Nelson, Frank Simon, Harry Anderson, Mike Caveney, and other names well-known in the tiny, close-knit magic world. Steve Forte’s Casino Game Protection (2004) and Poker Protection (2006) are the authoritative books about cheating at games of chance, featuring hundreds of my color photos.

“With my pal Mike Caveney, I co-published the definitive version of S.W. Erdnase’s The Expert at the Card Table, a classic 1902 book on sleight-of-hand cheating and card manipulation. Our edition, called The Annotated Erdnase, appeared in 1999 with extensive notes and commentary by the present-day expert, Darwin Ortiz.”

Further collaborating with Ortiz, Taylor produced, directed and photographed the documentary Darwin Ortiz on Card Cheating. However, “in spite of my fascination, I hasten to note that I don’t play cards or any other games, and have never wagered on any event, contest or proposition. I did lose a quarter once in a slot machine, a traumatic event.”

Taylor also designed furniture, clock cases, and dozens of pieces of jewelry. Examples of this work and some gallery photography appeared in the Visual Effects Society’s volume of members’ personal art, Vesage (2009).

Among other interests, including live concert music and 20th century composers, Taylor collected and photographed unusual timepieces. A coffee-table book of Taylor’s clock photographs, The Art of Pierced Brass, was published in 2012 by the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors.

While Taylor’s final screen credits include the short films Witchin’ and The Summer of Snakes, he never “officially” retired, noting, “The movie business has taken me all over the world and allowed me to know and work with some great artists. I have no intention of quitting; as the great production designer Henry Bumstead said while he was working in his 80s, ‘You’ll know you’re retired when they stop calling.’”

Special thanks to Peter Anderson, ASC and Jon Erland for their contributions to this remembrance.