Panavision at ASC Clubhouse for DXL Demo and Discussion

Following up their June 2016 unveiling of the new Millennium DXL 8K camera at the ASC Clubhouse, Panavision returned to the Society’s historic home on the evening of April 5 for an extensive presentation to showcase the camera’s capabilities and how it is being used with a variety of Panavision large-format optics. This program featured demo footage shot by Kramer Morgenthau, ASC and image examples and discussion with cinematographer Brandon Trost, who recently wrapped the first feature to utilize the Millennium DXL camera.

Active ASC members in attendance at the event included Andrzej Bartkowiak, James L. Carter, Curtis Clark, Peter Collister, Steven Fierberg, Alexander Gruszynski, Denis Lenoir, Isidore Mankofsky, Don McCuaig, Suki Medencevic, Alex Nepomniaschy, Crescenzo Notarile, Daniel Pearl, Mark Doering-Powell, Bill Roe, Pete Romano, Nancy Schreiber, Steve Shaw, Bill Taylor, Rodney Taylor, John Toll, Theo van de Sande, Joaquín Sedillo, Amelia Vincent, Roy H. Wagner, Steve Yedlin and Mark Weingartner.

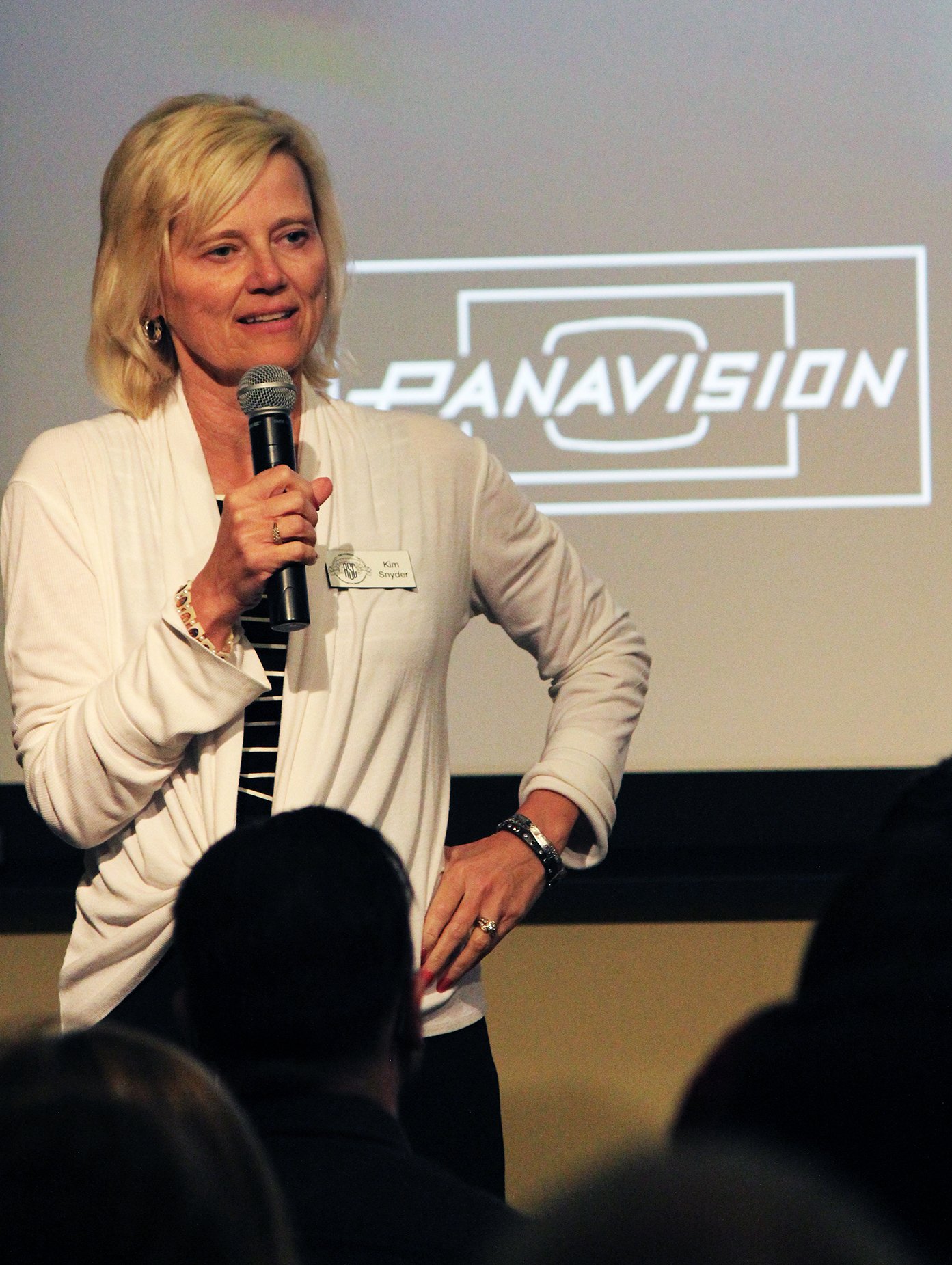

Following a dinner staged in the Clubhouse courtyard, where Millennium DXLs were set up for inspection as a wide range of demo footage was displayed on large LED monitors, the main presentation began inside with Panavision CEO Kim Snyder greeting the assembled audience and introducing Light Iron president Michael Cioni.

In his opening remarks, Cioni focused on his concept of the “Perfect Circle,” which serves to illustrate the capability of the DXL’s 8K imager. In short, he noted that any digital image is, of course, made up of polygons in a static grid, resulting in edges that are not in fact smooth or round, but jagged, and, while being essentially invisible to the human eye, create an idiosyncratic and perceptible “digital sharpness” that is exacerbated by the inherent contrast between pixels. He further explained that the DXLs 8K imaging system overcomes this artifacting by virtue of the sheer number of pixels available, which smooths out edges to result in an overall softer yet equally sharp and detailed image. The result is a “circle” image that is more “filmic” in nature, though Cioni noted that the DXL is not intended to replicate the photochemical analog process, and that film can nicely reproduce the “perfect circle” ideal in part because of its random grain pattern, while digital pixels are entirely uniform.

Panavision’s VP of Optical Engineering Dan Sasaki continued the discussion with his observations about how optical engineering and the image-recognition capabilities of human beings come into play when discussing the notion of image quality from a scientific standpoint. He further explained — using such fine-art examples as the Mona Lisa — how the human eye and brain register images of faces in a very sophisticated manner, how that played into the design of the DXL’s image processing, and how that picture is affected by different lens options used with the camera, resulting in different emotional responses from the viewer.

Cioni also announced that DXLs have been used in the field by a number of cinematographers — including Matthew Libatique, ASC on commercials, George Steel on a feature project, and Nigel Bluck on a network pilot — who have passed on their experiences and observations back to Panavision in order to help improve the product.

Cioni then introduced a short demo film photographed with the DXL by Kramer Morgenthau, ASC using a variety of Panavision large-format lenses, primarily for night work in moving cars under largely uncontrolled cityscape sources and, in one case, using an iPhone as his key.

(Click on image to play)

Cinematographer Brandon Trost (This Is the End, The Interview, Neighbors) was then introduced, as he had recently wrapped on the first feature to be shot with the DXL, a period drama entitled Can You Ever Forgive Me?, starring Melissa McCarthy and directed by Marielle Heller.

In designing a visual style for the modestly budgeted picture that was in keeping with the intimate subject and settings, Trost experimented during prep with shallow depth of field effects achieved through high ISO settings, low light levels and a variety of Panavision large-format lenses.

Trost settled on shooting at 3200 ISO, which, as Cioni put it, had the DXL turned “up to an 11.” The cinematographer noted that he liked the sense of depth this created, both in the shallow focus on his subjects — often in tight close-ups using wide lenses — and in the distant urban street vistas that were largely self-illuminated. “The way the backgrounds dropped off in terms of focus was also an advantage as our budget didn’t allow us to light extensively or dress the locations for the period, but you’d never be able to tell if a car going by in the background was a Prius.” He added that while shooting at such low levels did introduce some noticeable noise, he liked the effect, and it was appropriate for this particular project.

To help Trost achieve his desired visual approach, Dan Sasaki prepared three special sets of “de-tuned” lenses, which were sent to the cinematographer for testing. He jokingly described the third set as “Coke bottles” for being so soft, and expected Trost to reject them, but they ended up being the optics he used to shoot the picture.

The evening ended with the audience invited to examine several DXLs set up in the courtyard to see how they handled the site’s heady blend of tungsten and mercury-vapor lighting. One of the units was equipped with a prototype 600-nit, OLED, HDR/WCG Panavision Primo viewfinder, which was specially designed for use in very bright daylight.