Founders of the American Society of Cinematographers

Who were the 15 original members of the ASC when it was established in 1919?

By Robert S. Birchard

The American Society of Cinematographers succeeded two earlier organizations — the Cinema Camera Club, started by Edison camerapersons Philip E. Rosen, Frank Kugler and Lewis W. Physioc in New York in 1913; and the Static Club of America, a Los Angeles–based society first headed by Universal cameraperson Harry H. Harris.

From the beginning, the two clubs had a loose affiliation, and eventually the West Coast organization changed its name to the Cinema Camera Club of California. But, even as the center of film production shifted from New York to Los Angeles — the western cinematographers’ organization was struggling to stay afloat.

Rosen came to Los Angeles in 1918. When he sought affiliation with the Cinema Camera Club of California, president Charles Rosher asked if he would help reorganize the faltering association. Rosen sought to create a national organization, with membership by invitation and with a strong educational component.

The reorganization committee met in the home of William C. Foster on Saturday, December 21, 1918 and drew up a new set of bylaws. The 10-member committee and five invited Cinema Camera Club member visitors were designated as the board of governors for the new organization.

The next evening, in the home of Fred LeRoy Granville, officers for the American Society of Cinematographers were elected — Philip E. Rosen, president; Charles Rosher, vice president; Homer A. Scott, second vice president; William C. Foster, treasurer; and Victor Milner, secretary.

The Society was chartered by the State of California on January 8, 1919.

So, who were the 15 founders of the ASC? Some are among the best-known cinematographers of all time, yet others are not well remembered at all.

Here are their stories.

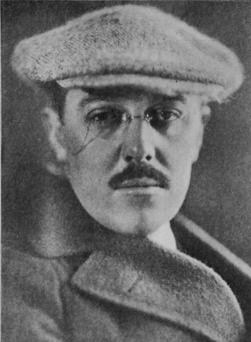

Philip E. Rosen

Born May 8, 1888, in Poland and raised in Machias, Maine, Rosen worked as a projectionist and lab technician before becoming an $18-a-week cinematographer in 1912. He became a co-founder of the Cinema Camera Club in New York City while working at the Thomas A. Edison Studio and later worked at Fox and shot several of Theda Bara’s pictures, including Kreutzer Sonata, The Clemenceau Case, The Two Orphans and Sin (all 1915).

Rosen came to California in 1918 to photograph George Loane Tucker’s The Miracle Man (Mayflower-Paramount, 1919), starring Lon Chaney. The success of the film brought Rosen an offer to direct from Universal, and over the next 30 years he helmed some 140 films.

He directed Rudolph Valentino in The Young Rajah (1922) and one of the most acclaimed films of the Silent Era, The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln (1924), but more often than not he was a director of efficient low-budget quickies.

Rosen was the first — but not the last — ASC member to give up his backward cap for a director’s chair and became active in the formation of the Screen Directors Guild in 1936. He served on their board and as treasurer through 1941.

At the age of 63, he died of a heart attack on October 22, 1951.

Homer A. Scott

Although he was a leader in the earliest days of the ASC and served as president from 1925–’26 — Scott has proven to be one of the more elusive founders. He was born in Cambria Center, New York, on October 1, 1880.

Scott’s earliest known credits are as cinematographer for actor Carlyle Blackwell’s Favorite Players Film Company in 1914. When Blackwell signed with the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company in 1915, Scott followed.

Beginning in 1916, he worked under the direction of William Desmond Taylor with Lasky’s sister company, the Oliver Morosco Photoplay Company, in a variety of genres, culminating in several films starring Jack Pickford. Among them were Tom Sawyer (1917) and Huck and Tom (1918). In 1921, Scott photographed Molly-O, starring Mabel Normand, for Mack Sennett. Over the next two years he shot all of Sennett’s feature projects, including The Crossroads of New York (1922), The Shriek of Araby (1923) and The Extra Girl (1923).

Scott never shied away from dangerous assignments. He was scheduled for execution in a Mexican jail as a rebel spy while photographing their revolution in 1912, but was finally pardoned after four tense days of uncertainty. During the making of The Right Direction (1916) for Pallas Pictures, a cavalry charge at his camera position resulted in a wrecked camera and Scott being hospitalized with “several painful though not serious injuries.” Scott remained cranking his camera until impact. He was trapped for six hours in a diving bell 30' underwater after a steel suspension ring broke during the filming of the Maurice Tourneur production Deep Waters (1920) off the coast of Catalina Island. He and an assistant were both unconscious when they were finally rescued.

Scott’s name appeared on the ASC roster for years, but his name disappeared from the credits of feature films after 1923. In that year, he was loaned to Warner Bros. to shoot The Little Church Around the Corner and is said to have started shooting Warners’ The Marriage Circle for director Ernst Lubitsch before being replaced. He is known to have worked as a second cameraperson for comedian Harold Lloyd, but he mainly did underwater work and other specialized cinematography in his later career. In the 1930s he did the marine work on Bird of Paradise, Tiger Shark and Below the Sea, among others.

Scott retired from films in 1936 and moved to the Newcastle district of Placer County to take up ranching.

He died in Sacramento, California, on December 23, 1956.

William C. Foster

A pioneer of cinematography, Foster was born in Bushnell, Illinois, on December 28, 1880, and went to work for the Chicago-based Selig Polyscope Company in 1901. At the time, Selig was turning out 50' and 100' actualities and trick films. Foster left Selig in May of 1911 to join Carl Laemmle’s Independent Moving Pictures Company. In 1915, he signed with the Equitable Motion Picture Corporation, working in New York and Florida.

Foster was lead cinematographer on the first five two-reelers that Charlie Chaplin made for Mutual Film Corporation in 1916 — The Floorwalker, The Fireman, One A.M., The Count and The Vagabond. He later shot a number of pictures with director Frank Lloyd, including A Tale of Two Cities (Fox, 1917) and The Silver Horde (Goldwyn, 1920) and also worked with director Lois Weber on pictures including To Please One Woman (1920) and What’s Worth While (1921). For a time, he was also the superintendent of the laboratories at Universal.

Active in the ASC leadership, Foster served the Society membership as treasurer and first vice-president, as well as on the Board of Governors

He died on January 18, 1923, from complications related to syphilis, politely described as the “general paralysis of the insane."

Lawrence D. Clawson

Clawson was a veteran of some 17 years behind a movie camera when he helped found the ASC in 1919. He was born on October 4, 1885, in Salt Lake City, Utah, and his first camerawork was in association with local theater manager Harry Revier, who started the Revier Film Manufacturing Company in Salt Lake City to produce pictures in 1910.

Clawson moved to Los Angeles in 1912, but his first known feature credits as a cinematographer are for director Lois Weber at Bosworth, Inc. and Universal in 1914–’15. He also worked for the American Film Company and Ince-Triangle-KayBee, where photographic superintendent and future director Irvin Willat would remember Clawson as “sort of like a news cameraman” who was not especially noted for his lighting style.

By the early 1920s, Clawson was chief cinematographer for the popular star Anita Stewart at Louis B. Mayer Productions, yet later in the decade he often worked as a second cameraperson. He was lead cinematographer on the early talkie Syncopation (1929), however his few remaining credits were for expedition films such as Hunting Tigers in India (1929) and low-budget productions including The Black King and The Horror (both 1932).

Clawson died in Englewood, New Jersey, on July 18, 1937.

Eugene Gaudio

The younger brother of future ASC member Tony Gaudio, he was born in Italy on December 26, 1886. He learned photography in his father’s portrait studio and developed an interest in movies around 1905. After coming to the United States, landing in New York City, he served as lab superintendent for IMP and Life Photo Film Corporation.

Arriving in California in 1915, Gaudio came out of the darkroom and went behind the camera for Universal Film Manufacturing Company — now Universal Pictures. The best known of his efforts as a cinematographer there was on the 1916 silent production of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

He later photographed films for Metro’s top female stars, Alla Nazimova and May Allison. His final work was with actress Bessie Barriscale’s B. B. Features.

Gaudio suffered an acute attack of appendicitis and tragically died on August 1, 1920, from general peritonitis after an operation.

Walter L. Griffin

Born in Fort Worth, Texas, on July 19, 1889, Griffin was a projectionist in a Los Angeles theater in 1910 and spent a year and a half in the lab before he first cranked a camera for Universal in 1914.

In 1915, he joined the Exposition Players' Corporation as the official cinematographers of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, where he headed photographic and lab operations. When the exposition closed in 1916, he spent four months in Colorado making scenic films for Denver Tourist Bureau.

Returning to Hollywood, Griffin signed on with the National Film Corporation where he shot some 25 comedies featuring National’s owner, William “Smiling Bill” Parsons. His best remembered film is Nomads of the North (1920) starring Lon Chaney, which was filmed for the National Film Corporation but released through the Associated First National Exhibitors Circuit after the untimely death of William Parsons caused the studio to close.

Through the early 1920s, Griffin ground out low-budget Westerns starring Bob Custer, Franklyn Farnum and Al Hoxie. In the mid-1920s, he gave up the wide-open spaces for the great indoors and shot a number of modest melodramas, including Rose of the Bowery (1927) and The Heart of Broadway (1928). His last known credit as a cinematographer was on City of Purple Dreams (1928).

In 1928, he retired from films and opened a florist shop and nursery on Lankershim Blvd., just north of Hollywood. He died in Ventura, California, on March 25, 1954.

Roy H. Klaffki

Born in California on March 6, 1882, Klaffki was a cinematographer for a dozen years or more, working in England as well as Hollywood, but, in 1922, American Cinematographer reported that “he prefers just now to be identified with the laboratory rather than the camera.

He had the title director of photography at Metro Pictures in the early 1920s — shooting films as well as supervising the work of other staff cinematographers and overseeing quality control in the lab. His pictures there included The Infamous Miss Revell (1921).

Klaffki took a similar position at Goldwyn in 1923 and later went on to shoot such pictures as Three Wise Crooks (1925), Queen O’Diamonds (1926), The Adorable Deceiver (1926; directed by ASC co-founder Phil Rosen) and The Impostor (1926).

His last feature credit was as associate cinematographer on the opulent and indulgent drama The Wedding March (1928), principally photographed by Hal Mohr, ASC. Directed by and starring Erich von Stroheim, it features Fay Wray and Zasu Pitts, and portions were photographed in two-strip Technicolor by Ray Rennahan, ASC. The shoot lasted eight months before Paramount pulled the plug; von Stroheim’s initial cut ran nine hours and a studio-edited version was not a success.

Klaffki would finish his career as a technician with the Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation.

He died on September 20, 1965, of malnutrition resulting from esophageal-tracheal abscesses with complications from pulmonary emphysema.

Charles E. Rosher

Born on November 17, 1885, in London, England, Rosher hoped for a diplomatic career, but his interest in photography led him to apprenticeships with still photographers David Blount and Howard Farmer. In 1908, he became assistant to Richard Speaight, official photographer for the British Crown. Rosher was invited to show his still work at the Eastman School of Photography, and when he came to the States to accompany the exhibit, he brought a Williamson movie camera and started shooting actualities. He was friendly with fellow Englishman David Horsley, who started the Centaur Film Company in the backyard of his Ideal Billiard Parlor in Bayonne, New Jersey, in 1907.

In 1910, Horsley offered Rosher a job, and the cinematographer came west with the renamed Nestor Film Company, arriving in Hollywood on October 27, 1911. When Nestor was absorbed by Universal in 1912, Rosher went along. He left in 1913 to shoot footage of Pancho Villa in Mexico and then returned to Universal briefly before joining the staff of the Lasky Feature Play Company.

Rosher became Mary Pickford’s cinematographer and photographed all her films from How Could You, Jean? (1918) through My Best Girl (1927). Pickford occasionally loaned Rosher out to other producers. One of these loan-outs was for Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Fox, 1927), which earned Rosher and co-cinematographer Karl Struss, ASC the first Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

Rosher fell out with Pickford when he was unwilling to shoot Coquette (1929) with cameras locked down in soundproof “iceboxes.” He had no trouble finding work at other studios, however, and earned six additional Academy Award nominations throughout the years. With his work on Kismet (1944), Rosher gained a reputation for his color work, and he received the Oscar for Best Color Cinematography on The Yearling (1946).

Rosher retired in 1955 and died in Lisbon, Portugal, on January 15, 1974.

Victor Milner

Born in Chavli, Russia, on December 15, 1891, Milner and his family arrived in New York City when he was 13. He first became interested in the movies at that age while attending dingy nickelodeons, watching the projector operators who were not yet hidden from view in fireproof booths. “The operator would let me take control of the projector whenever his girlfriend came to visit him,” Milner remembered.

He found a job with Eberhard Schneider, who manufactured motion picture cameras and other film equipment. His first experience cranking a movie camera came when he shot footage of a storm at Rockaway Beach. In 1913, at the age of 22, Milner shot his first feature film, Hiawatha: The Indian Passion Play, but he soon returned to shooting actualities, becoming one of the first four camerapersons hired by the Pathé News.

In 1916, Milner came to California on his honeymoon and heard that the Balboa Amusement Producing Company in Long Beach was looking for a cinematographer. He got the job and gave up newsreels for dramatic films. He later gained attention as second cameraperson on 17 films for Western star William S. Hart. Milner also worked at Metro and Universal, sometimes in the first camera position and sometimes in the second — as with Scaramouche (1923), which he co-photographed with future ASC member John Seitz.

Milner landed at Paramount in 1925 and spent the rest of his career at that studio, earning nine Academy Award nominations. He took home the Oscar for Cleopatra (1934). After shooting Jeopardy (1953), he retired.

He died on October 29, 1972.

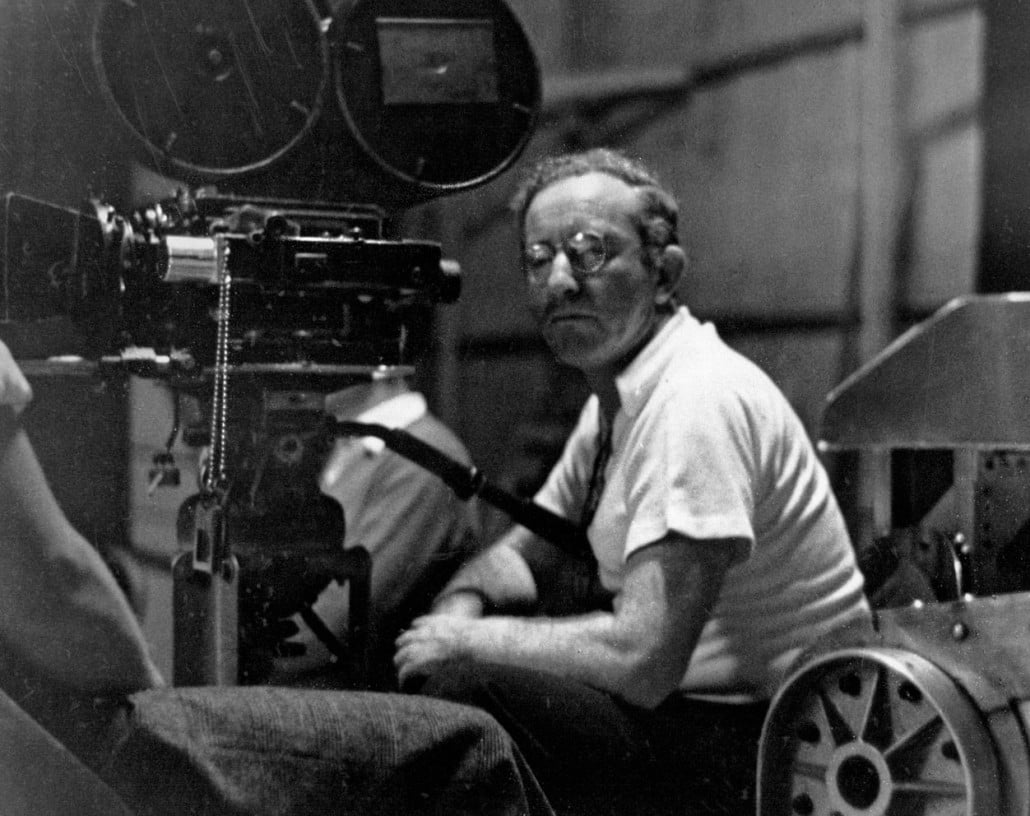

Joseph H. August

Known for his outdoor cinematography, Joe August was born on April 26, 1890, in Idaho Springs, Colorado, and grew up in ranch country. He gave up wrangling to began his film career as a cowboy at the Inceville motion-picture ranch in 1911, later becoming an assistant to cinematographer Ray Smallwood, a stern mentor who taught Joe to rely on his eyes. “There was a device… known as the ‘illumination system’… designed to obtain for the cameraman something parallel to what a meter would provide today,” August recalled in 1939. “I was told with considerable detail and even more emphasis just what fate would befall me if he ever found me fussing with one of those gadgets.”

August shot his first film, The Lure of the Violin, in 1912 and became chief cinematographer for Western star William S. Hart in 1915. He would shoot more than 40 of Hart's films, including Hell’s Hinges (1916), The Toll Gate (1920) and Hart’s swan song, Tumbleweeds (1925). August bragged that he never used a foreground reflector when working with Hart — though he sometimes utilized a white bed sheet to provide fill.

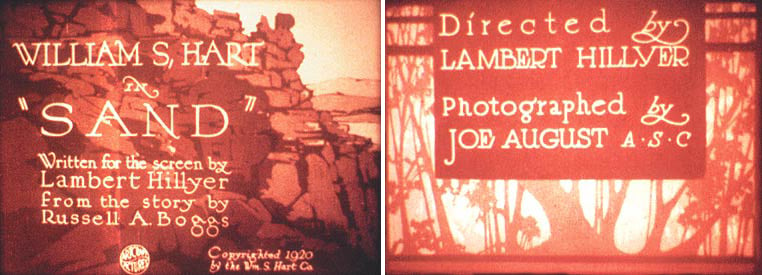

The first documented appearance of the ASC credential in a film’s titles was Sand(1920), produced by and starring Hart, written and directed by Lambert Hillyer and shot by August.

After Hart’s first retirement in 1921, August went to work for the Fox Film Corporation, where he did his first work with director John Ford on Lightnin’ (1925). August’s association with Ford would lead to shooting The Informer (1935).

Although acclaimed for his outdoor work, August was also known for his low-key lighting — a technique developed through necessity as lamps were a luxury and not terribly efficient in his early days behind the camera. With pictures including A Damsel in Distress (1937), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) and The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941) at RKO to his credit, August remained one of Hollywood’s top cinematographers, but he continued to rely on the principles he learned in the Silent Era. “Many things have changed during the rise and development of the picturemaking industry,” said August shortly after completing Gunga Din (1939), “but the basis of lighting seems to be about the same as it was in the beginning.” He earned an Academy Award nomination for this picture.

During World War II, August served with Ford’s OSS film unit, which was attached two the U.S. Navy in the Pacific Theater. He was wounded while shooting the Oscar-winning documentary short The Battle of Midway (1942).

August’s final assignment was the lush romantic fantasy Portrait of Jennie (1948), directed by William Dieterle, for which he earned his second Academy Award nomination. The film was nearing completion at the Selznick International Studio in Culver City when the cinematographer collapsed and died of a heart attack on September 25, 1947.

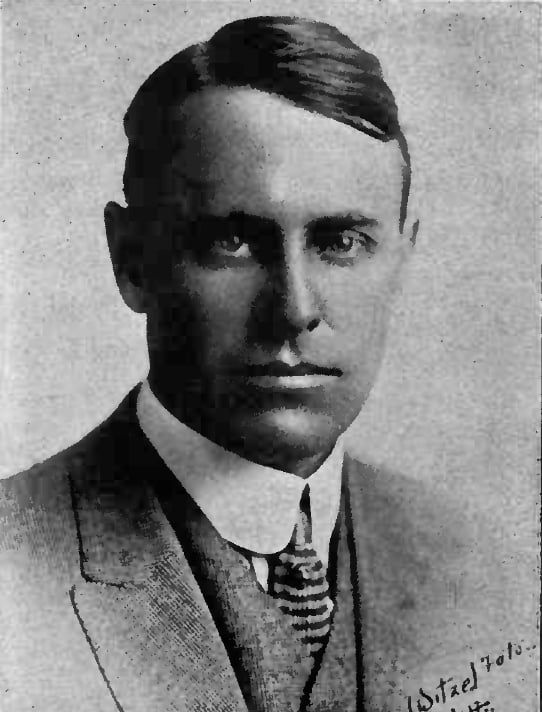

Arthur Edeson

This cinematographer’s credits include some of the best remembered films of all time: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1943), Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1935).

Born in New York City on October 24, 1891, Edeson was barely making a living as a portrait photographer in 1910 when he decided to try his hand at the movies. “I went to the old Eclair Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and applied for a job. While I was waiting in the outer office, a man came in and stabbed his finger around the crowded room, saying: ‘I’ll take you — and you, and you. Come with me.’ I couldn’t tell whether or not I was one of those selected, but I joined the group anyway. Once inside the mysterious recesses of the studio, I found I’d been hired — as an actor.”

Edeson never lost his interest in photography and began to shoot portraits of his fellow actors. His photos caught the attention of cinematographer John Van den Broeck, and when a cameraperson was taken ill, Van den Broeck suggested that Edeson fill in. “In those times, flat lighting was the rule of the day,” Edeson wrote. “However, I began to introduce some of the lighting ideas I had learned in my portrait work — a suggestion of modeling here, an artistically placed shadow there — and soon my efforts tended to show a softer, portrait-like quality on the motion picture screen. This was so completely out of line with what was considered ‘good cinematography’ in those days that I had to use my best salesmanship to convince everyone it was good camerawork.”

When American Eclair was reorganized as the World Film Corporation, Edeson stayed on to become chief cinematographer for the star Clara Kimball Young, and when she left for California in 1917, Edeson followed. In 1920, Douglas Fairbanks saw For the Soul of Rafael, one of Edeson’s films for Young, and signed the cinematographer for three of his biggest pictures — The Three Musketeers (1921), Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922) and The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Of Fairbanks, Edeson would say, “To anyone who worked with him, moviemaking today seems prosaic and cramped by comparison.”

Among Edeson credits in the 1920s were Stella Dallas, The Lost World (both 1925) and the atmospheric old-dark-house thriller The Bat (1926). At Fox, Edeson shot the first all-outdoor, 100-percent talkie, In Old Arizona (1929), and the first Fox Grandeur 70mm film, The Big Trail (1930). He later worked at Universal and MGM, and eventually settled in at Warner Bros., where he would remain until his 1949 retirement.

He died on February 14, 1970, in Agoura Hills, California.

Fred LeRoy Granville

Born Warnambool, Victoria, Australia, in 1896, Granville was educated in New Zealand. The February 1, 1922, issue of American Cinematographer stated that he was “a bloody Britisher by birth,” and “first saw the light at Worton Hall, Isleworth, Middlesex, England.”

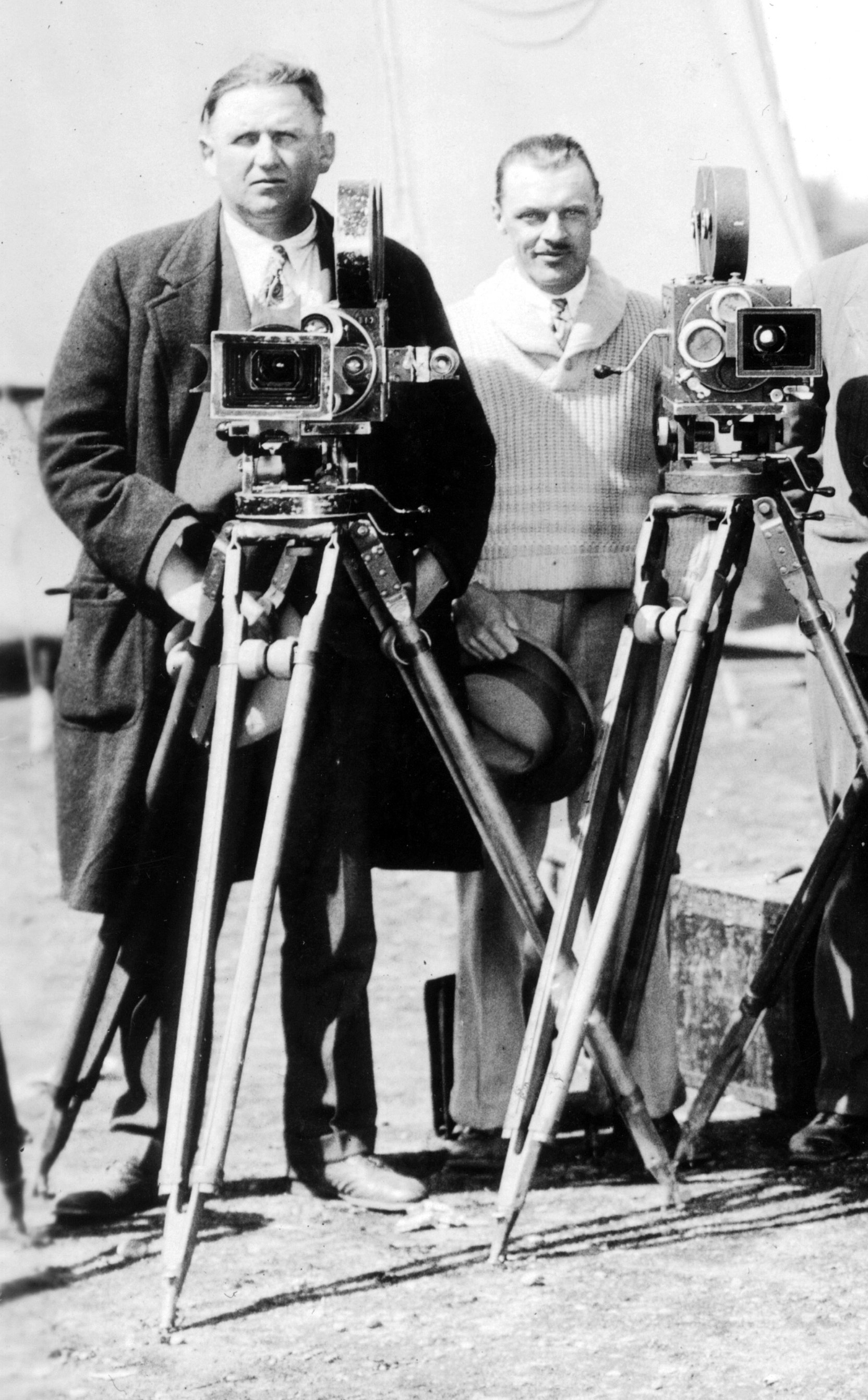

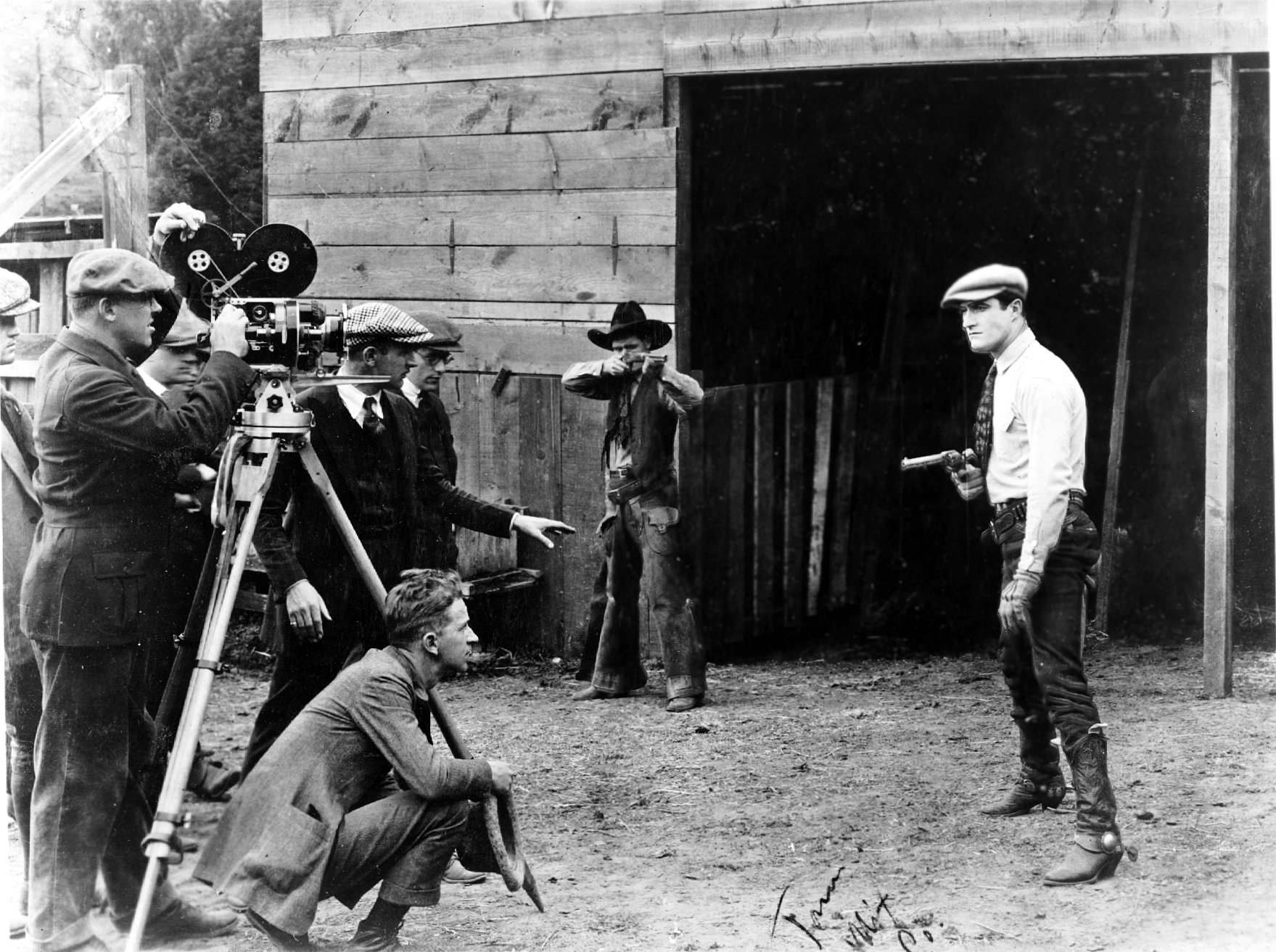

Granville became interested in photography as a boy. His first experience with cinematography came in 1913 under the guidance of James Crosby at the Selig Polyscope studio in Edendale, near downtown Los Angeles. Granville photographed the documentary Rescue of the Stefansson Expedition (1914) and a number of features and serials for Universal, including Liberty — A Daughter of the U.S.A. (1916) and The Heart of Humanity (1918). He also shot several of cowboy actor Tom Mix’s early Fox features.

In 1920, Granville went to England, where he worked as a cinematographer and director into the mid 1920s.

Granville died in London on November 14, 1932, from complications related to Bright's disease.

Of note, camera assistant Clark (seen in the photo above) would later become Mix’s lead cinematographer and close friend, and an ASC member.

Joseph Devereaux Jennings

One of the founders of the ASC, Jennings remained active in the motion-picture industry until his death.

He was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, on September 22, 1884, and graduated from the University of Utah. His film career began around 1913, after his family moved to Los Angeles, and his earliest confirmed credits are with Thomas H. Ince’s unit of the New York Motion Picture Corporation.

Jennings was an early member of the Static Club, and by contemporary accounts, was a gregarious guy. In its February 20, 1915, issue, the society’s magazine, Static Flashes, called him “the entertaining cameraman… Mr. Jennings is one of the active and popular cinematographers who believes in the future of the cameraman, and he is ever alert and responsive to the wishes of his director, aiding in the best of his ability in securing proper photographic results, and always appearing with a cheerful smile.”

His 1918 draft registration card reveals what could be a serious problem for a cameraman. Jennings was partially blind in his right eye, probably caused by an accident that occurred when he was seven years old and had been playing with gunpowder and matches. In the explosion, he was badly burned and it was feared that he might lose one of his eyes. But this physical disability doesn’t seem to have hindered either his career or reputation as an outstanding cameraman.

Jennings later worked for Fox, photographing Fame and Fortune (1918) and The Daredevil (1920) and other early Tom Mix features.

In the mid-1920s he shot several of Buster Keaton’s best-known comedies, including Battling Butler, The General, College and Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Following the untimely death of his wife Adele in 1928, Jennings became a director of photography under contract at Warner Brothers. While there, he shot 14 films, including Vamping Venus and The Public Enemy, as well as the early two-color Technicolor extravaganzas Bride of the Regiment and Golden Dawn. But as the 1930s wore on, he began to concentrate on special effects work — which he had dabbled in since The Lost World (1925) — finally settling in at Paramount, where his brother H. Gordon Jennings, ASC was the head of the effects department.

They shared an Honorary Award from The Academy for their outstanding work in Spawn of the North (1938), and later an Academy Award nomination for their work in Unconquered (1947).

J.D. Jennings, also known to be a fine golfer, died of cancer in his brother's home on March 12, 1952.

Robert S. Newhard

As early as 1922, Newhard was noted as being “one of the greatest aerial cinematographers in the world,” and it’s not surprising that he eventually found his niche in the industry as a specialized cameraperson in this arena.

He was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, on April 28, 1884, and began his film career working with Fred Balshofer’s Bison Life Motion Pictures unit of the New York Motion Picture Company in 1910. He stayed with the N.Y.M.P.Co. when Thomas Ince took over production reins and was behind the camera on several early William S. Hart Westerns, including The Bargain (1914) and On the Night Stage (1915).

After a five-year stint with Ince, Newhard worked three years at Paralta Plays, Inc. and followed this engagement with tenures at Fox and Goldwyn.

His last major credit was on Universal’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), although star Lon Chaney insisted that Virgil Miller, ASC photograph all of his closeups on that film. Newhard would receive first cinematographer credit on a handful of other films, ending with his only talkie, Party Girl (1930).

By 1933, the ASC membership roster carried Newhard’s name under the category of Second Cinematographers.

He died in Los Angeles on May 20, 1945, from the effects of bladder cancer.

L. Guy Wilky

His stalwart stand for collective bargaining brought a sudden end to Wilky’s career as a director of photography. He was born in Phoenix, Arizona, on October 12, 1888, and developed an interest in photography at the age of 10. After his junior year at the University of Arizona, Wilky took a job with the Philadelphia-based Lubin Mfg. Company’s southwest unit in Tucson during the summer of 1912. “I went back to the University to get my B. S. in mining engineering,” Wilky recalled, “and after graduating I joined Lubin again in Silver City, New Mexico. The director, Romaine Fielding, was having trouble with his cameraman and told me to learn as soon as possible so I could take over the job. We soon moved to Las Vegas, New Mexico, and it was there that I made my first picture, The Rattle Snake, in August 1913.”

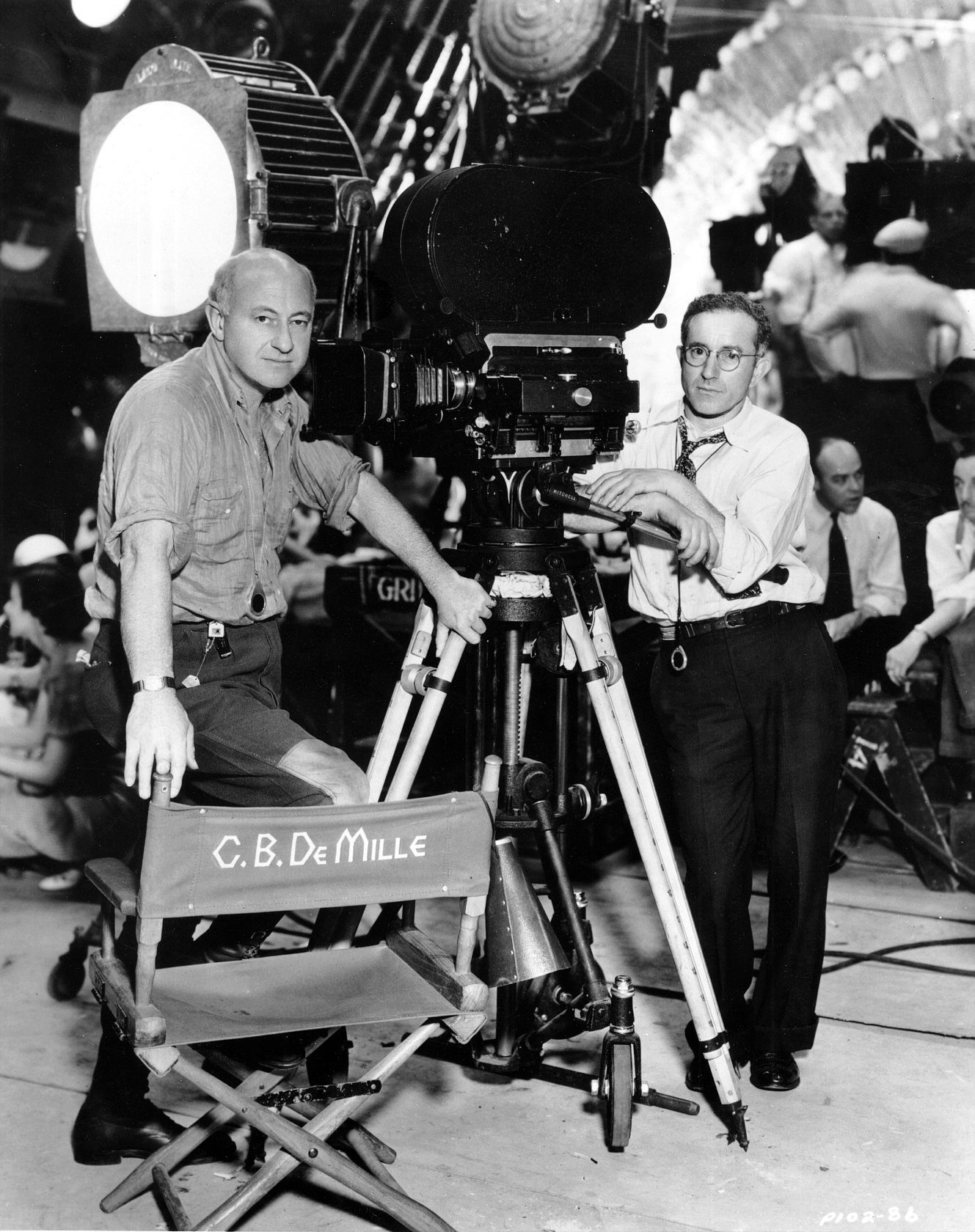

Wilky left Lubin in October of 1915 and went to California, where he worked briefly for Universal and then took a job with the American Film Company in Santa Barbara, where he worked with fledgling director Frank Borzage. “I was with American about a year. Then eight companies were canceled one week because of [World War I]… and the Borzage company was one of them. I didn’t get work again until January 1917 when I went to work for the Thomas Ince Company. I changed from one studio to another and finally got to Paramount, where I spent the best years of my career working with William C. and Cecil B. DeMille.”

Wilky was a member of the original Static Club, but dissatisfied with that organization: “It was just a social club without much interest in education. So a few of us… met at the home of one of the fellows and talked over the idea of a new and better club… that was the start of the ASC.”

Wilky was active in attempting to organize the International Photographers Union in the late 1920s, and his efforts led the major studios to blacklist him. After seven years at Paramount, his last credits as principal cinematographer were on a pair of low-budget pictures for Tiffany-Stahl in 1928.

He traveled to the south seas as second cameraperson on the classic Tabu, and later shot a film in Sri Lanka. But in Hollywood, he was relegated to working second camera on six-day “oaters,” and forced to give up his ASC membership because he could no longer afford the dues. He finally returned to the studios — and the ASC — as a second-unit cinematographer and assistant, finishing his career at Columbia in the 1950s.

When he received a 50-year membership pin at the ASC’s anniversary dinner in 1969, Wilky considered the token “one of my prized treasures.”

He died of a heart attack in Walnut Creek, California, on December 25, 1971.

Special thanks to David Kiehn, historian for the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, who contributed to this document. We also credit Lisle Foote for her exceptional research on Dev Jennings, which was done for her book Buster Keaton's Crew: The Team Behind His Silent Films (2014).