Last Rites: Filming 4:44 Last Day on Earth

Ken Kelsch, ASC and director Abel Ferrara take a gutter's-eye view of the end of the world.

A version of this story originally appeared in the April 2012 issue of AC.

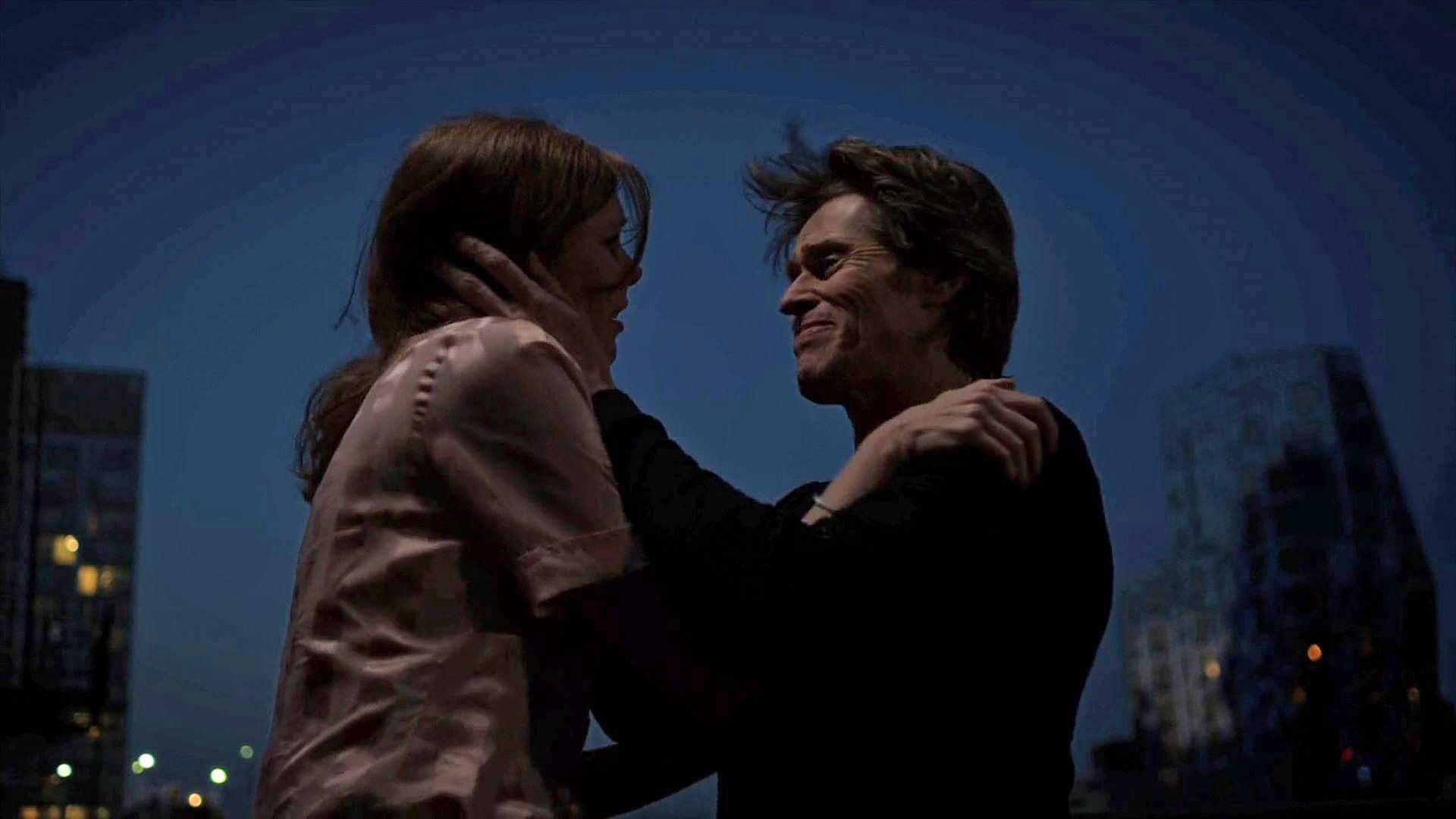

Photographed by Ken Kelsch, ASC, Abel Ferrara’s 4:44 Last Day on Earth takes place almost entirely in a spacious loft in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where aging actor Cisco (Willem Dafoe) and his painter girlfriend, Skye (Shanyn Leigh), spend their final hours engaged in meditation, painting, lovemaking and panicking on the day before the Earth is incinerated by a giant hole in the ozone layer. The end will come the next day at exactly 4:44 a.m.

Kelsch, who first collaborated with Ferrara on the 1979 grindhouse classic The Driller Killer, muses that the director’s films tend to project a “gutter’s-eye view of the world.” 4:44 is their 16th feature together.

“Abel’s strength — and this is why I love working with him — is that he always has a point of view,” Kelsch adds.

Redemption is a theme in many of the stories Ferrara chooses to tell, and in 4:44, Cisco struggles with regret as well as addictions.

“Yes, this is a film about addiction, and it’s also about sobriety,” says the director. “But this is not a documentary. This is an episode of The Twilight Zone.”

“You do what you have to do to get a movie done...”

— Ken Kelsch, ASC

Kelsch shot 4:44 in 4K with a Red One upgraded with a Mysterium-X sensor. Although Ferrara has used digital capture on a number of projects, including the documentaries Chelsea on the Rocks and Mulberry St., he observes, “I don’t dig it. I’ve spent my whole life shooting film, and these newer HD cameras come close to the texture, to the shadows, but I’m just not going to turn around and know how to shoot digitally.”

Kelsch, on the other hand, felt confident enough about digital acquisition to recommend it for 4:44. “Abel had had a very bad previous experience with the Red One, but I think it’s difficult for a director to judge the intrinsic value of an imaging device with someone else at the controls,” he reasons. “This was my fifth project in a row with the camera.

“You do what you have to do to get a movie done, and Offhollywood gave us a great deal on posting a Red project,” Kelsch continues. “Maybe digital wasn’t the all-around best choice, but if we’d had to shoot on a [Canon EOS] 5D, I would have.”

Kelsch chose Cooke S4 prime lenses because he believed they would render the most flattering digital image.

“Digitally photographing actors over the age of 30 terrifies me,” he says. “I don’t want to see every wrinkle on the actor’s face. The S4s are a lot more forgiving than the [Arri/Zeiss] Master Primes.”

Ferrara’s films are known for possessing at least a certain amount of grit, and although Kelsch doesn’t consider himself “a heavy filter guy,” he tried to slip a Tiffen Pro-Mist in front of the lens for some of Leigh’s close-ups. “That was quickly nixed by ‘Il Duce,’” he quips. “Abel doesn’t like beauty shots, but half of the cinematographer’s job is taking care of the actress. I want to make women beautiful when they’re supposed to be beautiful, and when they’re not supposed to be beautiful, I want to have control over making them look less attractive.”

The way Ferrara sees it, staging most of the film’s action in one location presented more opportunities than restrictions: “You know what Hitchcock said about shooting in a telephone booth, right? ‘It’s great! There are so many things you can cut to!’”

The filmmakers often used television, digital tablets and video chats as windows to the outside world. “I was directing actors in other countries over the telephone,” Ferrara recalls, referring to a scene in which a Vietnamese delivery boy (Trung Nguyen) video-chats with his family in Vietnam. “What am I going to do, build a room and cast those people? [Nguyen] had a family sitting right there!”

At one point, Cisco leaves the loft to walk to a friend’s apartment in the East Village. For the exterior shots, Kelsch relied mostly on ambient streetlight, sometimes using a single Nine-light Maxi-Brute to enhance the exposure. The Red’s ISO was set to 640 or 800, depending on the shot, with the aperture “wide open and hopin’,” says Kelsch.

In the loft, Kelsch worked with Ferrara to lay down some concrete visual guidelines. They saw the last day on Earth unfolding over a series of chapters, each with its own look. On set, digital-imaging technician Charlie Anderson created lookup tables to complement the different lighting schemes.

“The morning look has light coming in through the windows where Skye is painting,” Kelsch explains. “We were very restricted in terms of placing lights outside; we had no cranes or Muscos to bring up the exposure inside.”

Instead, he and gaffer Dan Gartner used 4x4 Kino Flos and an Arri 6K Par to raise the interior exposure, sometimes adding ND.6 or ND1.2 to the windows to match exterior light levels. When Cisco steps onto the patio, a series of nets helped reduce the exposure outside, allowing Kelsch to move from interior to exterior without an iris pull.

In the late afternoon, Cisco awakes from a nap in a panic and runs back onto the patio just as the sun sets. Magic hour descends, and after watching a neighbor jump to his death from a nearby fire escape, Cisco contemplates his own suicide. “We shot that scene over four different magic hours, with incredible variations in the day and night sky,” recalls Kelsch. “That sort of light exists at the ideal conditions for maybe 20 minutes.”

But Ferrara pushed Kelsch to roll the camera even before the sun started to set. “You wouldn’t believe the mismatched exposures,” Kelsch continues. “In post at Offhollywood, it took us all day [to match the shots] in Scratch with windows and mattes. It was a slow and difficult process, but we shot raw and had a really dedicated colorist, Milan Boncich, so we were able to pull it off.”

“In the darkness is the imagination.”

— Abel Ferrara

When night falls, Cisco and Skye walk around in the dark, wading through shallow pools of light cast by the overhead Kinos and gravitating toward dim computer and TV screens like moths. “Abel is the original ‘Turn that light off’ guy!” remarks Kelsch.

“In the darkness is the imagination,” says Ferrara. “If you hold up a film negative, there’s black between the frames. In a two-hour movie, the audience is literally sitting in the dark half the time. I think that’s where the film is made.”

The run-and-gun nature of the production — a 15-day schedule with a six-person grip-and-electric team and a three-person camera crew — was further complicated by Ferrara’s freestyle approach, which required Kelsch, Gartner and key grip Bryan Landes to keep their equipment out of the actors’ paths.

“With Abel, you can’t put a light on a stand, because as soon as you do, you’re going to be shooting in that direction,” the cinematographer says. He therefore backlit most of the night interiors with the ceiling-mounted Kinos and used a Litepanels Ringlite Mini to add a small amount of fill.

“At first, Abel was horrified by the Ringlite — he thought I was going to front-light Willem and Shanyn,” Kelsch recalls. “But when he realized I could use it for just a tiny bit of eye-light, he loved it.”

Once the set was lit, Kelsch found himself operating the camera (assisted by 1st AC Franziska Schirmer Lewis) and trying to keep up with the actors. “I love it when Kenny operates the camera,” says Ferrara. “It’s a grind on him because he’s lighting, too, but it’s great for me because I can have one conversation with the camera department.”

“I’ve suffered holding the camera for hours on end, but I like to operate,” says Kelsch. “You develop close relationships with the actors.”

There’s little to suggest that even if he didn’t like operating, Kelsch would refuse his director’s request. “Sure, sometimes we argue, but I want his image to be perfect,” he says.

Ferrara expresses a deep admiration for Kelsch’s contributions, despite their occasional disagreements. “Ken’s a giving person, and he’s got an attitude about film that’s different than mine. But anyone who’s part of my set affects the film. You gotta believe, and I know Kenny believes even when we’re not seeing eye to eye. Because we’ve had a relationship for so long, we have a funny way of expressing that.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.85:1

Digital Capture

Red One

Cooke S4