A House of Dynamite Visualizes the Unthinkable

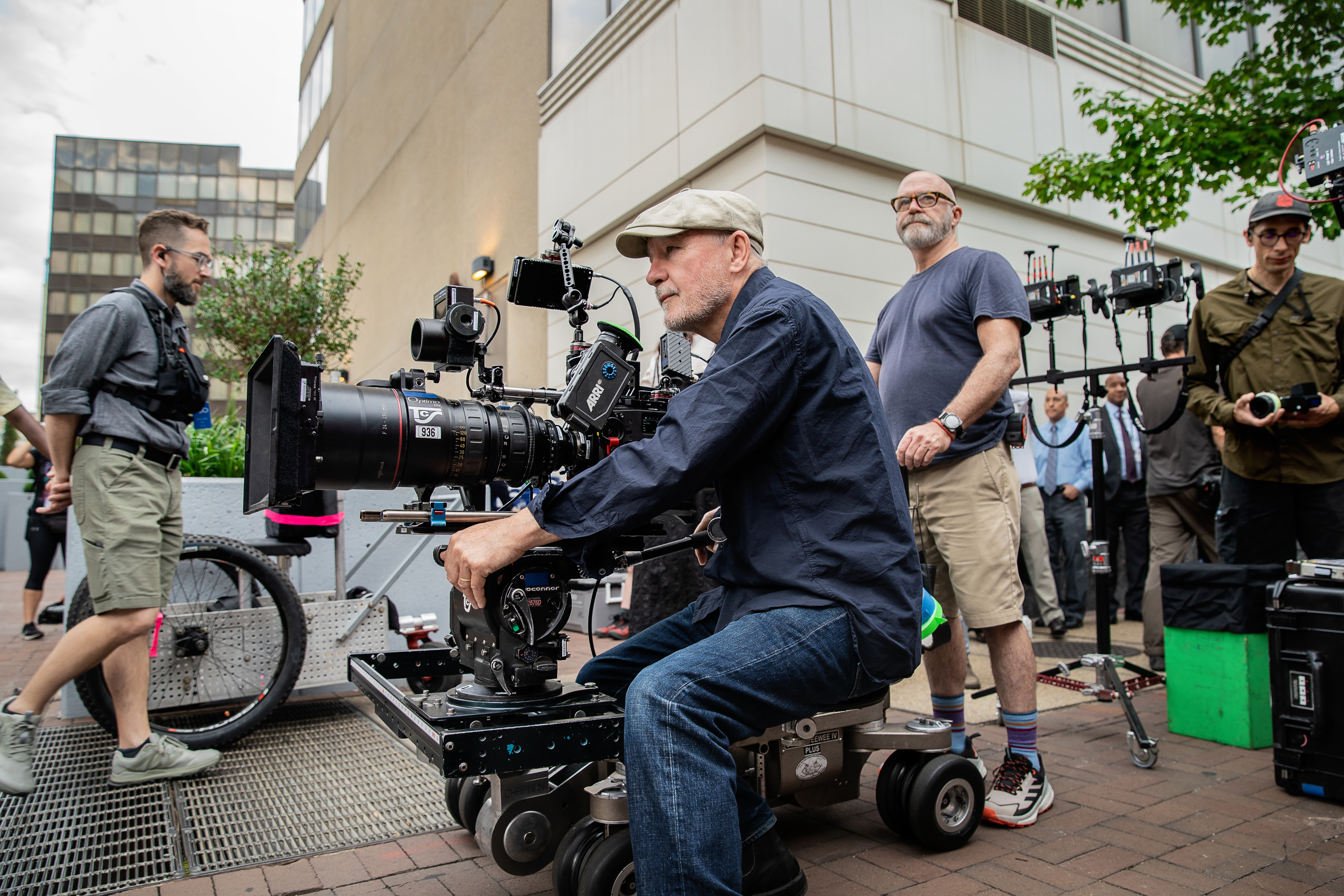

Barry Ackroyd, BSC puts a premium on realism for Kathryn Bigelow’s nuclear-war thriller.

This in-depth look at the making of A House of Dynamite first appeared in American Cinematographer's January 2026 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

The agile, kinetic approach to cinematography Barry Ackroyd, BSC has honed over the years reaches an apex in Kathryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite, which sees U.S. government and military officials responding to an unknown enemy’s nuclear-missile attack on Chicago from three perspectives. It is Ackroyd’s third feature with Bigelow, following the Best Picture Oscar winner and ASC Award nominee The Hurt Locker (see AC July ’09) and Detroit.

Rooted in many years of documentary shooting, Ackroyd’s technique — also showcased in high-tension dramas with Paul Greengrass such as Captain Phillips (AC Nov. ’13) and United ’93 (AC June ’06) — emphasizes the human perspective, seeking to place the audience in situations difficult or uncomfortable to imagine and keep them there. Most of the cinematography in House of Dynamite, Ackroyd says, “comes from a human position, an eye level — maybe lower, maybe higher, but roughly in the realm of where we see the world. It should be someplace where you feel you could have been.”

Fluidity is key to that sense of intimacy and immediacy, and Ackroyd, who does his own operating, achieves it by relying on zoom lenses, most often an Angénieux Optimo Ultra 12x 24-290mm T2.8. “The 12:1 lens has this beautiful ergonomic feel, designed so I can use the left hand not to hold the camera, but to be active and use the fingers to respond with the zoom. [In House of Dynamite] the camera is on a 3- or 4-foot-long slider; it’s fluid in the way a human being can move — leaning, sliding left and right to get around the subject to open up the story and small moves that reveal the subjects.”

Capture Tools

Regarding his longstanding collaboration with Bigelow, the cinematographer observes, “I think the reason we hit it off is because I already had a deep documentary background and an understanding of how to achieve a more truthful kind of imagery. That formed the basis of what I was trying to do, and then Kathryn gave me all this freedom and kept saying, ‘Let’s do more.’”

On The Hurt Locker, which Ackroyd captured on Aaton Super 16mm cameras, “more” meant more cameras and more operators. “We found a way to manage four cameras shooting handheld simultaneously,” he recalls. “We were dancing around the live action, capturing whole scenes rather than breaking everything down shot by shot. It was a process heavily influenced by my experience with documentary.”

Bigelow noted in an interview with Netflix, “My first film with Barry was The Hurt Locker, and that’s where we developed this language of keeping the movement within the frame very free and giving the actor tremendous latitude. It was interesting because there is always a bit of concern from the cast about the blocking. But then, the only blocking you do is your job to the best of your ability — anywhere within a 300-yard space. It then becomes very credible very quickly. There is a logic and a credibility to how the scene is shaped. It’s a very fluid process.”

On House of Dynamite, the filmmakers opted for digital capture with the Arri Alexa 35. “I like the look and the cameras themselves,” says Ackroyd. “They’re ergonomic, and the look is filmic. Those are all things that are important to me.”

The production was typically a three-camera shoot, with Gregor Tavenner and Kathrine “Kat” Castro joining Ackroyd to operate. “Three [cameras] was ideal for this, except when we did some of the bigger street scenes, some battle re-creations, and some shots of cavalcades of vehicles driving through Washington, D.C.,” says Ackroyd. “In those instances, we brought in more cameras, as well as helicopters to cover all of our aerial shots at one time.”

On set, Ackroyd always has Cooke prime lenses at hand: “We had the whole set of S4/i lenses available, using them for handholding or for specific shots, but by day three, when we set up the camera, I found myself saying, ‘Oh, let’s go with the 12:1 24-290mm. That lens might stay for the rest of the day.’”

Sometimes a new location or setup required a lens change: “I’ll think, ‘Okay, now we’re in a smaller space, we need to use a smaller zoom,’ and we’ll switch to the [Angénieux Optimo T2.6] 28-76mm. It’s not complex — nothing I do would be.”

Manipulating the focal length is essential to Ackroyd’s style. “I may go from 50mm to 290mm in the same shot,” he says. “You know, it’s not a fixed thing.” He loves to put his eye to the camera, assess what’s in front of it and decide, “That is the frame.” If the script supervisor asks for the lens size of a certain shot, Ackroyd’s response will be “various, because we went from 40 to 120 on that zoom and then back to 75.”

“Don’t Worry, Just Get the Camera!”

Much of A House of Dynamite takes place in government situation rooms that are generally unseen by outsiders — large spaces equipped with enormous screens, control panels, computers and phone lines. Under the supervision of production designer Jeremy Hindle, the filmmakers built these interiors onstage in New Jersey at CineLease Studios. Ackroyd recalls, “We had three huge stages completely full of builds, which is unusual for Kathryn and for me because we both like real locations.”

Hindle designed replicas of the “Watch Floor” intelligence center in the White House Situation Room; the U.S. Strategic Command (“StratCom”) headquarters in Washington, D.C.; Fort Greely observation post in Nebraska; and other key facilities.

Ackroyd notes that he, Tavenner and Castro shot to make these settings feel more claustrophobic and ramp up the tension. Camera support was necessary because of the size and 24-pound-heft of the Optimo 12x. “We would have the camera on dollies — and we’d have sliders, maybe 3 or 4 feet long,” Ackroyd says. “We weren’t using huge pieces of equipment because we didn’t want to lose that sense of the human scale.”

With smaller lenses or in tighter spaces, he would frequently shoulder the camera. “You definitely can [go handheld] when you’re using smaller lenses, whether they’re zooms or primes,” he says. “Being squished in a car — I’m still the one who volunteers to do it. I’m getting old — I am old! — but my suggestion to camera operators is to do yoga, climb in, cross your legs, and say, ‘Don’t worry, just get the camera!’”

Stark Realism

Some of the film’s lighting was highly controlled, whereas other setups were at the mercy of nature. For instance, Ackroyd shot the exterior establishing shots in summer, often in the middle of the day, giving them a stark, bright look. He recalls, “It was a very harsh, very hot summer, and we didn’t have the luxury of getting [those shots] at 7 or 8 p.m. — we had to film them at midday. So, in that sense, they’re only captured, not shot with the most beautiful of light.”

Although the filmmakers had complete control over the lighting onstage, beauty wasn’t the goal there, either. “Government buildings aren’t known for their beauty,” Ackroyd notes wryly. “A lot of these buildings have poorly positioned downlights that seem to be almost random, and they have a lot of variation in the types of lights, from LED standard lamps to soft diffusers.” He and his crew rewired “hundreds of small fittings that were rigged into the set. Gaffer Andy Day and our talented dimmer-board operator, John Duncan Jr., put them all back through dimmers so we could color-correct or dim, so we knew what color temperature we were going to use for our approach. If in a corridor, for instance, we felt it should be more fluorescent, we would have a tinge more green in that.”

Setting up all the sources and the methods for controlling them comprised most of the prep onstage. While shooting, Ackroyd and his team would attach Arri SkyPanel lights hanging off camera, but this was limited because of reflections and the logistics of shooting with three cameras. “We were using the whole space, so you’re looking in all directions, and it’s sometimes difficult to hide lights in these environments,” Ackroyd says. “At times, some of the actors would hit an ugly piece of light, but we wouldn’t stop filming. We wouldn’t say, ‘Stop, you’ve got to be in that light over there — don’t go near that.’ What the camera does is give space to the actors without any marks or restrictions, and they like that.”

Video calls play a significant role in the action and dialogue, and rendering them posed singular challenges. In many scenes, a character appears on location, and then in another perspective we see that same character on the land line, computer or large LED screens. For instance, we initially see U.S. Gen. Anthony Brady (Tracy Letts) on a video call on the Watch Floor; his face has to appear on several screens. In a later scene, we see the same events from the StratCom location, with Brady at his desk watching other characters via video. “We had to film, light and transmit live sequences that had to be linked into the StratCom location,” Ackroyd says. “We had video screens with live performances all on a surveillance-camera rig, which took a lot of cooperation and a great deal of work from many departments. We used everyday video rigs capable of 4K resolution, so that the image could be dropped into our live coverage or degraded to look more like a wireless cam.”

Extra Emphasis

The final color grade, which Ackroyd carried out at Company 3 in New York with ASC associate member Stephen Nakamura, provided another way to create emphasis. “When we’re looking at a shot,” says Ackroyd, “we have to ask ourselves, ‘Does the look of the shot take you to this character or to that character? Does the focus take your eye? And do we sense the reality?’” The grade had to account for a variety of shots, he adds, from different angles off all three cameras. “You have so many different skin tones on set, and the lighting can be very unflattering to one actor but not the guy next to him. So, it’s a balancing act.”

But the goal in the grade, as with everything else, was immersive realism. “Kathryn and I really want the audience to believe it,” he says, “to bring the audience into the screen rather than for the screen to jump out at them. We’re trying to make people feel that there’s no other place they could be.”

Unit stills by Eros Hoagland. Images courtesy of Netflix.