Bold Strokes: Marty Supreme

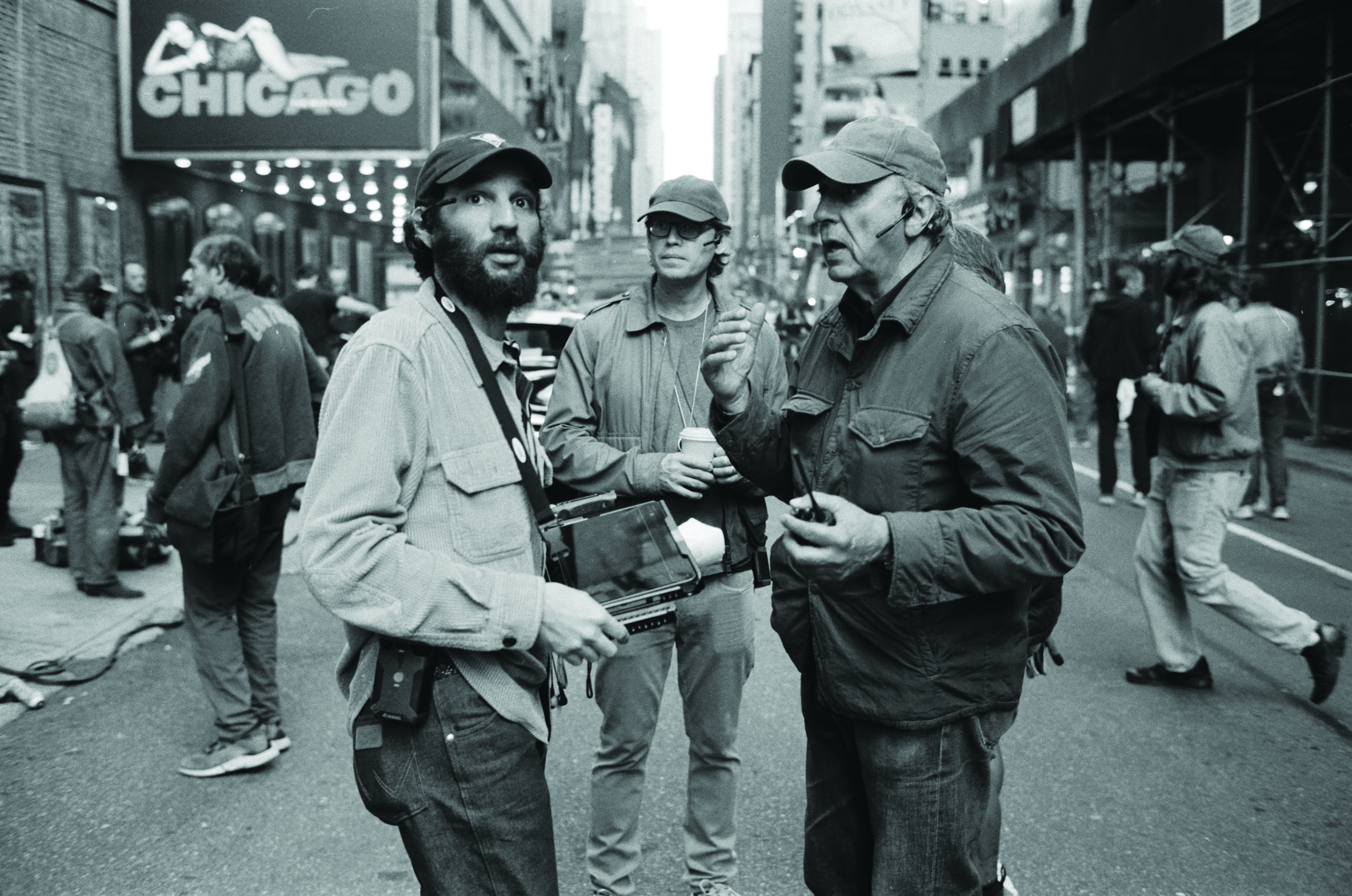

Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC helps director Josh Safdie put wild topspin on the tale of a ping-pong prodigy.

This in-depth look at the making of Marty Supreme appears in American Cinematographer's January 2026 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

When AC’s editors approached me about interviewing Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC about Marty Supreme, I leaped at the opportunity. Khondji has been on my “favorite cinematographers” list for as long as I’ve been keeping one. His work has graced nearly every genre, from psychological thrillers to epic dramas, and his unique ways of visualizing stories have become an important force in modern cinema. Prior to our Zoom interview, we had only met socially at industry events; now, I’d finally have a chance to talk shop and deconstruct his process in detail.

Marty Supreme is Darius’ second film with director Josh Safdie. (The first, Uncut Gems, was co-directed by Josh and his brother, Benny.) The story of a talented young man obsessed with a dream, it is a film of many moods, and it unfolds as a gritty character study — something long missing from mainstream movies.

To wit: It’s 1952, and Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet) is trapped in a dead-end job selling shoes at his uncle’s store on New York’s Lower East Side. Marty’s life is a stifling routine that he’d never have chosen for himself. His rare talent for table tennis is a potential avenue of escape, and he becomes obsessed with pursuing a world championship. His overbearing mother (Fran Drescher); pregnant girlfriend (Odessa A’zion); and an indifferent, often hostile world conspire against him at every turn, but no obstacle can keep Marty down.

The resulting journey is a wild ride with nonstop energy and more twists than Coney Island’s Cyclone roller coaster. Here’s how they did it.

American Cinematographer: How did your relationship with Josh Safdie first come about and lead to Uncut Gems?

Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC: I had met Josh at various screenings and events, before Uncut Gems. My daughter had helped Josh and his brother, Benny, fund one of their other films. I loved their energy and their films.

Then they asked me to shoot a music video. I had seen their films and was very interested in the way they were made. So, we did this music video for Jay-Z in New York [“Marcy Me”]. It was very exciting, very different than what anyone else was doing, and very low-budget, and I imagine they were seeing how I’d react on a project like that. It was a crazy shoot — on land, in helicopters — and we worked almost nonstop. At the end, they said, “Would you shoot our movie? Would you read the script?” I said, “Yes, of course.”

It’s interesting how sometimes we find our collaborators at the right moment.

They kept telling me, “It will never be like this on a film — it will never be so crazy.” I had done music videos before, and I knew that sometimes that’s just the way we must work — you must adapt to a system creatively. Uncut Gems was like that. Marty Supreme is of a different scale, of course, but it’s the same idea: You have to hold on! It’s like a boat on the sea during a storm, and the boat is rocking. Yet, you hold on, and you slowly get there.

Marty Supreme is such an expansive, fast-moving story that takes place across many locations. How did you find a visual through line that would hold it all together?

It was a case of following Josh, from a script that was electrifying. Even though he and [co-screenwriter/co-editor] Ronald Bronstein changed elements of the story every day, they were making it better and better. But a big part of my job was to be close to Josh all the time; you just have to enter his world and know exactly what he’s doing, stay updated on everything and keep everyone focused in one direction, little by little.

This was a period piece that takes place during the early 1950s, so there was a totally different world of imagery. I’d photographed period films before, and I loved those experiences, but with Josh, [the feel and emotions of the story] felt modern, very much like how we’re living today. Then, you join that photographically with the design, the costumes and a soundtrack featuring songs not from the 1950s but from the 1980s, and it becomes more about the tone and emotions of a certain period in the character’s life. It’s also an anthropological study of someone living in 1952 in New York City, and his crazy feelings and the goal that he is completely and very selfishly taken in by. It’s a search for who he is, subconsciously in a way; then, at the end, he comes to realize what life really is about, what mankind is about, and what his future holds.

Photographically, we wanted lenses with old glass. The “realness” of the film comes from the characters — their faces, the differences between people. I knew we were going to be filming very close to them, as if we were using a magnifier; we were going to be obsessively tight on them, searching their faces through their eyes and through their character as people. And so, we selected lenses that would take us in this direction, mostly very long anamorphics, almost like having binoculars or a magnifier when looking at the characters. We used long zooms, too.

I noticed that quite often you used long lenses, in a sense, also as wide lenses.

Exactly. This was Josh’s preference, and I endorsed it. So, early on during testing, we started using long lenses more and more. It was a process. We became one because of this, in the way we wanted to tell the story. I mean, there’s no normal — everything is a different experience — but let’s say on movies in general, when you do a wide shot in anamorphic, maybe you’ll use a 40mm or a 50mm, or even 25mm or 35mm. But here, we’re using 65mm, 75mm or 100mm lenses to tell the story not in wide shots, but more like medium or medium-tight shots. But we filmed everything in a very free way, so we didn’t have to worry too much about what to see or not to see.

Jack Fisk’s production design and Adam Willis’ set decoration are superb.

Jack is a wizard — he’s the greatest! Everything was made like it was old period. The important thing is that you have to dirty-up everything — not putting dust on it, but making it really look real, as if it’s a bit wrinkled. Timothée’s skin tone is like the moon, so we added things to make it seem more “real,” like acne. We shot tests with him — hair, makeup, contact lenses, glasses, every detail.

We made everything in the film what we thought was more real, in a way, but also more exciting. We always thought of adding layers — more layers between — and a lot of that was Jack’s design. He gave us the freedom to shoot in different directions for exteriors where there’s nothing period-correct in today’s New York. If you’re trying to convey the ’50s, it’s very hard to shoot there today, even downtown; you have one angle here, one angle there, a little bit that really transports you into period, but to link everything is very difficult. And Jack did many amazing things. It was a very, very exciting process.

I grew up in New York, so I’m familiar with the texture of the city, and you did a magnificent job of not calling attention to any of it and just letting it be part of the film’s fabric.

No, Jack Fisk did it. We painted some areas, and we hid things with trucks all the time. On exteriors, there were traps everywhere — traps you had to put layers on. And after we scouted, we had to keep visiting various places to see how they were changing, little by little.

You originated on film?

Yes, most of the movie is on film, and that brought me so much pleasure, because I don’t shoot film so often anymore — sometimes I do on a commercial. Marty Supreme brought me back to loving film; I just wish we could make a new, fast stock with an interesting grain structure that we could play with in the processing! I think one of the reasons I liked shooting film on this feature is that we were always so tight on these lenses, so close to the actors, and I really love the texture of film on faces. It’s something very different. I love manipulating the processing, choosing the lab, and using the lenses to add layers and to photograph the souls of the faces. Josh loves film. I never resist shooting film, but now I’m more inclined to shoot film than to shoot digital — it’s just an incredible pleasure. I’d really like to shoot large format!

More on Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC

Khondji Unpacks His Groundbreaking Approach to David Fincher's Seven in 1995

Khondji and His Collaborators Reflect on His Storied Career

Did you actually print any film?

For release, we made 35mm and 70mm prints. We did some tests at FotoKem, and the people there are terrific allies when you want to shoot film.

It’s ironic that we struggle so often to make digital look like film. It would be so much easier to just shoot film.

That’s what Josh is saying all the time.

Did you use any filtration on the faces? The complexions were so carefully modulated.

If you use the right lenses, they do their own filtration. I use filtration, but it’s filtration you don’t see. I have more and more of a hard time using the type of diffuser that you really see onscreen. I used to do it more openly, but now it has to talk with the story. I’ll use filtration sometimes for blending, for putting on a layer, for blending color and faces or characters in the landscape. You always tell your story inside the story; you tell yourself your own story, of images inside the story you’re reading. Sometimes I use a Tiffen Ultra Con or their Smoque filter, which just gives you a pattern. I use them on film as well, and sometimes I use a very light Mitchell — the old, classic Mitchell diffusions — or a [Tiffen] Classic Black Soft. When I do use diffusion, I always use the lowest graduation of the filter. But, you know, I say this now, and then I’ll shoot something else and maybe take another approach!

You’ve referenced the lenses and how important they were to crafting the look of this movie. Which did you use?

Mostly Panavision C Series and B Series — I love them both. We had this very beautiful 360mm we used a lot. Often, our wide lenses were the 75mm or 60mm. And, of course, exceptionally, we had to sometimes use a 40mm or even wider because we were in a place where it was the length we had to use. That’s the widest we ever went.

It must have been quite a challenge for your focus puller.

Very, very tough. Our focus pullers were [A-camera 1st assistant] Craig Pressgrove and [B-camera 1st assistant] Anthony DeFrancesco. We also had two amazing camera operators, Colin Anderson and Brian Osmond, and a magnificent gaffer, Ian Kincaid, who came to New York to do the movie. And we had my friend Richard Guinness Jr. as key grip, along with dolly grip Joe Belschner. Richard was an amazing leader of this great group of brothers. We always work together and we’re also close friends. And Joe is like a guardian angel for me, always making sure everything is right. He plays music, and he’s like a musician on set. I love being surrounded by musicians. When people tell me they play music, it always makes me excited to hire them. I’ve always believed that camera movement and even lighting and color have everything to do with rhythm and music.

But on such a sprawling production, how do you maintain that rhythm consistently and keep everyone moving in the same direction?

We were lucky to have everyone following Josh’s lead. Obviously, I was following him faithfully, and so were all the other heads of department. They were passionate! They realized we were all there to make his film. People were not dragging their feet or lying back; instead, they were attacking, going forward and not playing in a defensive way. Everybody was excited.

Tell us about the small bits of the movie that you shot digitally.

Our amazing DIT, Gabriel Kolodny, stayed on for the entire film, even when we were shooting film. He helped me manage the stop changes and everything we did to make it work. As for shooting certain parts digitally, you’ll have to just guess where we did that! Wherever those shots are — they may be a small portion, they may be a huge portion — it’s seamless in terms of the look. The real magicians were Gabriel and [senior colorist] Yvan Lucas at Company 3. Yvan is an artist. I remember shooting my first short films with him when I started my career in France, and then he moved to the States. But he was back with me on Eddington and then on this film.

We also had this young and talented man, Ryan Marie Helfant, serving as 2nd-unit director of photography, and his work was wonderful. These were the people surrounding us, and they were persistent. Cinema is a special thing that we are lucky to be able to do, and I feel we were all thinking that.

The lighting is so beautifully done that the film doesn’t feel “lit” at all.

I don’t have a go-to lighting unit, really, and you’re gonna laugh — I always forget what I use from one film to the other! I apologize to the great technicians reading this, but I don’t remember everything I use. I used tungsten light, which I love. HMIs were once a big nemesis of mine, but then I learned how to use them effectively. And, of course, the greatest was the Brute Arc, but I got to use it so rarely. But LED is also great; it depends what you do with it, how you use its power, how you use its color. I can ask people to watch scenes that have been lit by LED lights that look like old tungsten.

You know, you always have to look at a setup with discernment and distance and think about the light, the color. Is it right or not? It’s all a question of how you use the intensity, the height and distance of the light to the actor’s face, and how you play with it, how you filter it.

Ian was a wonderful adviser. For the table-tennis scenes, we did some tests with different types of light, including modern, diffuse quartz, box LEDs and mushroom lights. And we ended up using the mushroom lights because there was nothing more beautiful coming down on the faces. The way the light hit the faces, and the propagation of the light around it, was just perfect.

In the large venues where table tennis is played, instead of just flooding areas with light, you localize the light to a great extent, and the effect is amazing.

I had lots of talks about this with Josh. For me, those sequences had to be “poorly” lit by a kind of single-direction source. The effect had to be dark and a bit murky and not pretty at all. So, we just used a key light. Ian, of course, had given me all the options for adding more lights, but we found the most beautiful look was that one-direction light.

Sometimes I really believe in what I call “poor light,” because in the old days, there wasn’t light everywhere in cities. If you want to do period, you have to turn lights off all the time. I remember taking Polaroids in New York during the ’70s, and there was very little light — you had to do long exposures to get it right. In this film, these ping-pong players are traveling to different cities in Europe. I had to imagine the cities where they were traveling and make them different and “dirty.” And this was done in concert with the characters. Lights sometimes work with the characters, with the story, and this was one of those times.

There’s a tendency today for cinematographers to light spaces and let the actors wander where they may. That is most certainly not the case in this film.

Yeah. I mean, it depends on the location and what you’re going to do. Sometimes the director says, “You have to see in every direction.” I sometimes smile at that because I don’t know what to think. You do it, but then you always have to light for the close-up. You always have lights coming in on the fly for close-ups — or flags, you know. But, of course, this is what we learn: what to do and how to do it.

Everything you did feels purposeful, yet at the same time, it doesn’t feel that the actors were constricted in any way. The look is naturalistic yet very spicy.

Thank you, Richard; it’s really good that you say that. You have to have a belief. You have to believe that when you expose film, it’s going to happen, that the light is going to be there, and that the exposure is going to get there. Of course, you don’t go crazy or do dangerous things. In the shoe store where Marty works, for example, we put bulbs here and there, creating soft little pools of light. When we’re doing our lighting, we sometimes add additional fixtures or change to more interesting types of units. I used [Rosco] DMG Dash Lights a lot. I loved that unit for not only the eyes, but sometimes for just a tiny bit of organic fill.

How did you generate the black-and-white newsreel footage?

Josh wanted a very contrasty look, and he wanted to match some newsreels that he really liked. Ryan Marie Helfant did this work with the 2nd unit while we were shooting the main body of the film. He was very good, very dedicated and open. And he was extremely helpful.

I was fascinated by the scene that shows the bathtub falling through the ceiling.

We did that with careful planning and multiple cameras. There was very little use of effects. When you write action like this, it’s poetic in a way. Practically, we storyboarded the shots, but ultimately, the director and actors did everything.

You know, I never watch my films. I do the color-correction, and then I see it once with an audience in a real theater. But I’m going to see Marty Supreme probably two or three times. It’s a movie I really enjoy watching because I learn things from it all the time. I’m not contemplating my work, because I forget my work; if I look at it, I’ll be always very critical. Instead, I’ll look at the actors. I can’t stop watching them. Now I take pleasure in watching the camera pan to see Jack’s work, or when the camera slows down to show Miyako Bellizzi’s amazing work in the costumes. It’s just fantastic seeing cinema at that level.

The playing in the table-tennis scenes is so acrobatic and sensational. Did you shoot any of that live?

Those sequences were all done live. The balls were added digitally only in some scenes, but the actors were playing together live. Sometimes they had to pantomime, but mostly the balls are real. Timothée trained for a long time, and he played with really good players. Koto Kawaguchi, performing in the role of the Japanese player Koto Endo, was very, very good; he is a top player in real life. All the faces you see around the tournaments were those of actual ping-pong champions.

Tell us about the final-grading process.

The base of the work we did on set was there, and after the grade, we did a filmout to a print. Our approach was very classic. I mean, it’s not film. Film is a process I love, certainly more than the DI. I just find the DI to be one of the most dangerous areas of filmmaking. It can be the most beautiful and helpful thing for us, but it can also be very cruel. I know from experience that the DI can destroy and deconstruct. You have to be careful whether you do a modern story or are remastering a film that you’ve shot in the past. You have to be careful of desktop ideas. You have to think about what the film is.

Are you ever truly satisfied when you finish a project? Do you come to some sort of peace with what you’ve done?

That’s a good question. I’m always very critical of things. It depends on how I watch the film.

Conrad Hall [ASC] once told me there wasn’t a single frame he wouldn’t have done differently if he’d had the chance. I was shocked to hear that from one of the all-time greats

I don’t like perfection. I try not to be perfect, you know? That’s the least of my interests. I love dirtiness and I love layers, and the love of perfection is a crazy quest. I’m talking about when perfection is interesting, at the level that Hall or Gordon Willis [ASC] achieved, where it becomes like a religious experience, but I don’t feel like I’ve reached that level.

When you’re on the job, to what extent does it take over your life?

I get sick afterwards, because the process takes so much from me. I’m not saying I’m more focused than other people, and I would never think that, but I’m totally taken by the work — it’s my life. Sometimes people say, “You’re not going to stop. You won’t retire.” Well, this is my life! I hate to make a parallel with a battle, but it’s like a battle, and my ideal death is to die in action. But doing a film like Marty Supreme makes me want to work another 200 years.

Unit stills by Atsushi Nishijima. Images courtesy of A24.

Tech Specs

Aspect Ratio | 2.39:1

Format | 4-perf 35mm (anamorphic)

Cameras | Arricam LT, ST, SR; Bolex

Lenses | Panavision B Series, C Series; Optica Elite

Film Stock | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219

The Director’s Perspective

American Cinematographer: Tell us about your collaboration with Darius.

Josh Safdie: I first became aware of him in high school when I saw Delicatessen [1991; directed by Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet], and then later, his other work — and [those movies] shaped the way I looked at film. They were so clearly filled with a passion and a love for the medium. And that’s something I look for when I’m hiring somebody — their exuberance, their soul, their spirit and their passion — because they bring a lot more than their technical prowess. Darius is a film-lover first, and light is a physical thing for him. You see it in the way he runs his hands through the air when he’s talking about the type of light he wants to use in a scene. You can feel it. There’s a real romanticism in his outlook on life, his outlook on films.

How does that translate to working together on set?

He’s so humble in the way he helps me lead the entire operation. He focuses on the light and the physical medium of film, how he’s going to expose and process it. Then, he’ll look at my frames and give me his point of view — and in his elegant way, it always makes things better. When he agreed to shoot Uncut Gems [2019], I found a family member. In terms of visual references, we didn’t look at other movies. We talked about them for their feeling, not for their cinematography. We looked at some photographs, but it was really the way he saw the faces and the locations in which we were most aligned.

You showed a real affinity for long lenses on this film.

I’m a subjective thinker. It’s incredibly important to human survival; we need to understand each other’s points of view, and that’s how we’ll survive. And I believe that long lenses and the minimizing of depth of field allow for an “imperfection.” It’s how the eyes work. Our field of vision is very wide, but if you’re interacting with people six feet away from you, you can’t focus on anything else. I think I was 19 or so, and I learned to zoom all the way in on the camcorder. And when I used a 16mm Bolex, I fell in love with the 75mm, which is the equivalent of a 150mm on 35mm film. It was an instant attraction to the way it made me feel.

At one point, I think we filmed with a 3200mm for the close-up of Gwyneth Paltrow in the arena. The camera was on the other side of the stadium, and she said, “So, this is a wide shot.” She was flabbergasted to hear it was a close-up! But it really compressed the image and it made you feel like you were in it, almost like a dream.

How did Darius feel about that approach?

He knows lenses so well and was very good about being aggressive with them. He would call the Panavision C Series anamorphics his “jewels,” his “eyes.” So, he ended up falling in love with the long lenses, especially using them in anamorphic, because it’s somewhat counterintuitive. He really is a romantic, and in sports you call that an invisible stat. You can’t see it on the page, but you can feel it in the film. You know, this is not a job for just any of us.

— Richard Crudo, ASC