Revolution and Revenge: One Battle After Another

A crack camera team, led by cinematographer Mike Bauman, helps Paul Thomas Anderson bring an ambitious political thriller to the big screen.

This in-depth look at the making of One Battle After Another appears in American Cinematographer's November 2025 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

VistaVision is experiencing a renaissance. Following its use on last year’s The Brutalist (which earned cinematographer Lol Crawley, ASC, BSC an Academy Award for Best Cinematography), the 8-perf 35mm format, with its native aspect ratio of 1.50:1, provides the visual foundation for two major 2025 features: Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle AfterAnother and Yorgos Lanthimos’ Bugonia.

VistaVision seems particularly suited to Anderson’s film, an eye-popping political thriller that follows reclusive ex-revolutionary Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio) as he embarks on a frantic search for his teenage daughter, Willa (Chase Infiniti), after she’s abducted by an old nemesis, Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn). The film was inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s novel Vineland and marks cinematographer Michael Bauman’s fifth collaboration with Anderson; Bauman served as gaffer on The Master (AC Nov. ’12) and Inherent Vice and as lighting cameraman on Phantom Thread before advancing to cinematographer on Licorice Pizza, which he co-shot with Anderson.

Bauman says the director has “always been fascinated” with VistaVision, which he tested for The Master (shot by Mihai Malaimare Jr., ASC), adding, “One Battle After Another provided us with such a big canvas to be able to use it.”

The key members of the show’s camera crew, comprising Bauman, camera operator Colin Anderson, 1st AC Sergius Nafa, key grip Tana Dubbe and gaffer Justin Dickson — a group Anderson calls “the Five-Headed Monster” — was in unfamiliar territory with the format and conducted extensive experimentation in prep. Bauman recalls that the aesthetic buzzword was “texture,” and a key reference was The French Connection (shot by Owen Roizman, ASC) for its gritty, grainy imagery. Anderson’s directive was, “It’s got to look like a ’70s movie,” says Bauman, and “the looseness of The French Connection and The Last Detail really set the tone.”

Updating the Tech

The filmmakers shot with three vintage Beaumont VistaVision cameras; two came from Geo Film Group, but the primary body was borrowed from actor-turned-cinematographer Giovanni Ribisi (Strange Darling; AC Oct. ’24). Nafa recalls drily, “It was instantly apparent that the cameras would require a serious technical update with regard to peripherals and uniformity. The challenges for me were range, logistics, film run-time duration and Mr. PTA’s unabashed proclivity to ask for what my guarded, technical mind had previously considered impossible. However, as I went through the requirements to deliver on these requests, I began to realize that most of the time, they could be furnished.”

ASC associate member Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy, supervised the calibration and upgrading of the cameras. “Our engineering team assisted with the design and fabrication of parts to make the cameras easier to service and maintain,” explains ASC associate member Guy McVicker, Panavision’s director of technical marketing. “Handheld, studio, stabilized-head and aerial-photography components were all purpose-built, along with general AKS [accessories], as none existed to support what the film needed. We also built a prototype viewfinder for the A body to allow a brighter, sharper image for the operator.”

The Panavision team engineered further refinements during production, including new pressure plates and a new video-assist system. “The crew was able to use all of these upgrades before the film wrapped, and the upgrades yielded better camera systems for [other] filmmakers, ensuring that the VistaVision format will continue to be viable and reliable,” McVicker says.

Watch: Michael Bauman on One Battle After Another (Interviewed by Eric Steelberg, ASC)

The filmmakers spent more than a year testing Ribisi’s camera, which Bauman calls “fixing the plane while flying it.” The camera often jammed because the take-up motor had trouble handling 1,000' loads; the solution was cutting them down to 800'. In addition, the crystal-sync motor, which connects to a 144-degree shutter angle, had to be adjusted in order to function reliably.

Another consideration with the Beaumont cameras is that they’re very noisy. So, a blimp was built for shooting a few dialogue-heavy scenes with the Beaumont, and the filmmakers sometimes resorted to shooting other dialogue scenes, particularly interiors, in Super 35mm with two Panavision Panaflex Millennium XL2s. These camera systems included latest-generation video assists first introduced on Twisters.

A Full Serving of Lenses

Sasaki created a package of 63 spherical lenses, which “resembled a buffet of glass when they were all laid out,” says Bauman.

Sasaki explains, “Many of the lenses that were ultimately used had to be modified to clear the VistaVision camera mirror and ground-glass assembly. Paul had used our Super Speed lenses on other projects, including Phantom Thread, and he’s always loved the look of the movies Gordon Willis [ASC] shot with them. He wanted that look with VistaVision, but nothing really existed that worked for that format. So, through our conversations, we ended up building a new set of prototype prime lenses, which is now up to 12 focal lengths [from 14mm T2.8 to 100mm T1.8], all of which cover VistaVision. The lenses have a nice flare quality, and skin tones render in a very pleasing way. If you’re framing a subject in close-up, the background falls off nicely while more of the subject’s face stays in focus.

“In addition to the prototype lens set,” Sasaki adds, “we developed a lens that emulates the look of a ‘gun scope’; a special 6mm T4 fisheye that covers full frame; and multiple simple compound lenses, such as Tessars, triplets and symmetrical lenses, for close-focus work. Lens development for this show was continuously evolving. Suggestions and requests for additional focal lengths or lens types continued well into production. This was a fun show that constantly kept us on our toes!”

Many of the lenses tended toward the warm side, especially Anderson’s personal collection of glass, which he calls the “GW” (named in honor of Willis). That look, Bauman notes, was what the director responded to most strongly. In fact, those color aberrations became a key element of the film’s aesthetic. Rather than trying to keep the look consistent, the cinematographer says, “Paul told Kristen Zimmermann, who timed our print dailies, to leave all of the aberrations in.”

Finding the Light

One Battle was shot mostly on location in Northern and Southern California and El Paso, Texas. The goal was to maintain a light footprint and extreme mobility so the team could essentially find the light. Their lighting approach mixed color temperatures and often relied on neon and fluorescent tubes for interiors.

Dickson recalls, “The sequence for me that really stands out is when we were filming in Eureka at Bob and Willa’s house. It was raining nonstop and the location was very small. I think only PTA, Mike Bauman, the actors and the camera crew could be in the house because it just couldn’t fit everyone. We started out by lighting through the windows with Mole Richardson 12-light Maxis and CTB for correction. After just constant downpour, we switched to Creamsource Vortex8s and Nanlux 2400Bs with Fresnels because we knew they’d handle the downpour and give us the stop we needed.” Inside the house, the filmmakers deployed a mix of LiteGear LiteMat 4s, Rosco DMG Dash lights and practical sources.

One Battle begins 16 years before the story’s “present day” with a rush of adrenaline as Bob, an explosives expert, helps the radical paramilitary group “French 75” storm an Immigrations and Customs Enforcement detention center to spring the detainees. Bob is infatuated with hard-core revolutionary Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), but their thrilling life of crime gets complicated with the birth of their daughter, Willa.

The sequence was shot on a quickly assembled set near the border wall south of San Diego. In fact, the view from the freeway underpass revealed actual immigrants crossing the border with the production’s background actors. “That area was lit primarily with strategically placed practicals,” says Bauman. “Flo had created a space that had LED light practicals. Inside the tents and buildings, we had a mix of LED and fluorescent sources. The LED light towers didn’t have any way to adjust output, so Justin and Tana made various levels of neutral density that could be applied to lower the intensity. The look we achieved had a really interesting energy and an aesthetic of industrial ugliness: The set decorator, Anthony Carlino, placed silver blankets all over the ground and we kept adding fixtures, mixing the cool feel of the LEDs with these other color temperatures, like sodium vapor.

“Even if the lights were overexposed, we’d shape it in some way,” the cinematographer continues. “We did one shot in an area, where the soldiers are walking through the cages and you see the kids inside. I had to do a stop pull from a T1.4 to a T22 in one shot. I’d never done that kind of a pull before! There was a lot of improv going on, so we were constantly adjusting intensities as things were happening.”

Respecting the Improv

The filmmakers also responded to extensive improvisation between DiCaprio and Benicio del Toro, who plays Sensei Sergio St. Carlos, a martial-arts instructor who shelters immigrants. Bauman recalls that Anderson would block out the space and let the actors play, which led to a number of happy accidents. “They would start just riffing on something, and that looseness defined so much of our approach, in terms of how we lit and grabbed those moments,” Bauman explains.

One scene in El Paso — when Bob rushes into Sergio’s dojo asking for assistance — was reshot for additional lighting. The sequence was initially lit with fluorescent tubes. “We never rehearsed that the lights were going to shut off and they were going to stand in silhouette,” says Bauman, “but we happened to have a condor a block away, carrying four Vortex 8s and three Fuze Max Profiles, and we could get just enough height so we could shoot the light from the condor into the room without really seeing it. The overall ambient level in the room was very high because we couldn’t dim the fluorescent lights, so we were adapting to that. When that interior light level dropped, we still had the edge from the condor.”

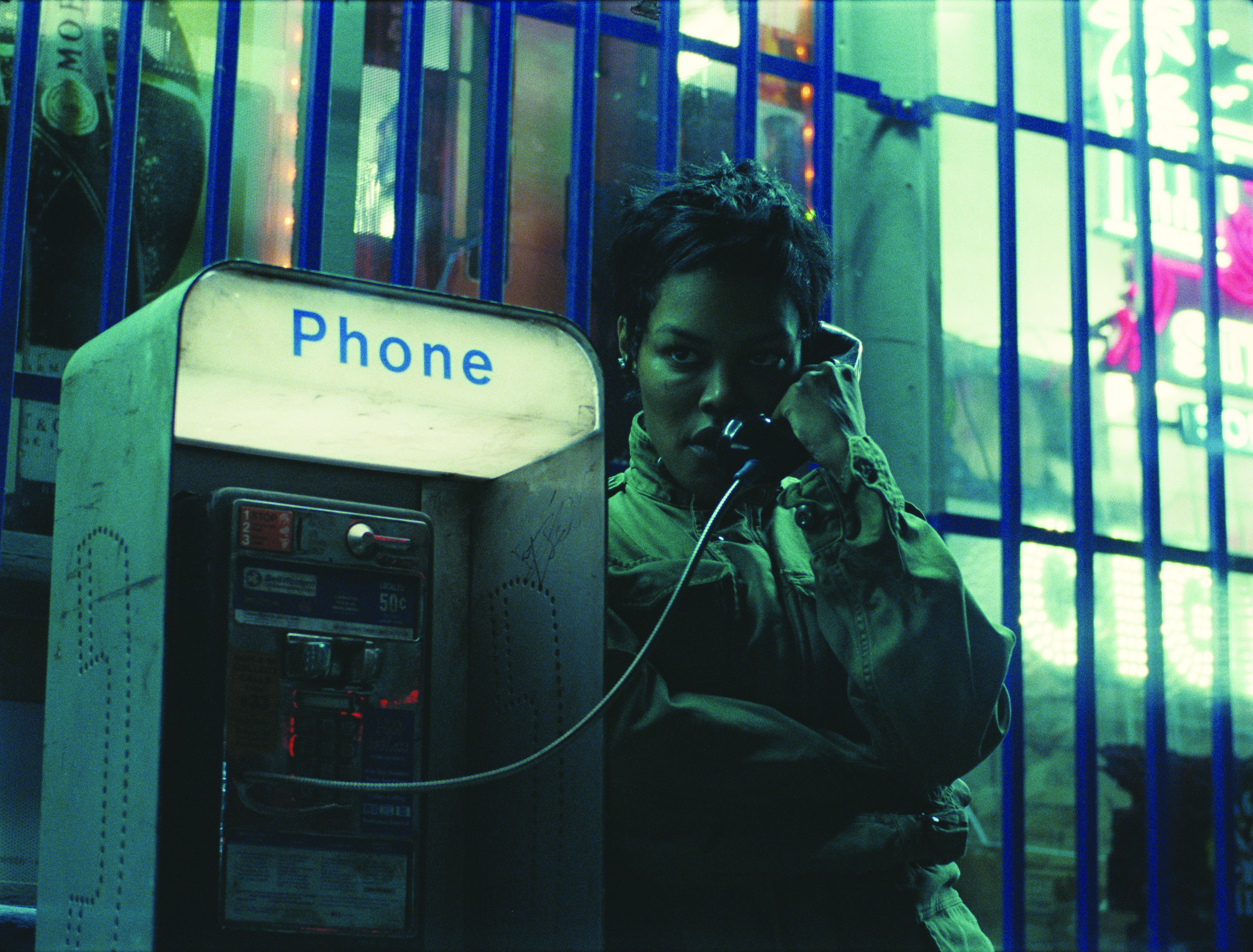

Another set where the filmmakers adjusted on the fly was Sergio’s apartment. Production designer Florencia Martin and crew created a multi-room apartment complex that we were able to move through fluidly,” says Bauman, noting that the build included a second floor so the actors could go upstairs, come downstairs, and be outside. During a key scene on that set, DiCaprio was performing his character’s side of a phone call when the actor spontaneously pulled on the curtains, causing them to fall down and expose the street beyond and below the windows. “Leo just played with it, and it was like, ‘Okay, the light is this way now,’” says Bauman. “Justin added a projection on the wall using a Fiilex Q8. It was about having messiness and embracing light that wasn’t sculpted. We had to respect the improv, so we had a lot of small sources on set that we could hide quickly.”

Hot Pursuits

The film’s car chases provided their own challenges for shooting in VistaVision. They include a bank-robbery getaway filmed in Sacramento; a chase involving Bob and Sergio, staged in El Paso; and a bravura chase with Willa taking charge in Borrego Springs, San Diego, known as the Texas Dip. Nafa recalls, “The magic-hour chase sequence in the rolling hills of Borrego Springs required some quick reloads and tactical positioning of support to accommodate a run that was miles long. The cunning genius and piercing wit of [the late] 1st AD Adam Somner in these pressure situations helped me execute to the level necessary to thread multiple [VistaVision] cameras at different check points — and keep the images from eluding capture! I think the gravity of the scene itself will properly convey what I was feeling at the time, and that [the sequence] will certainly stand out for the audience.”

Some of the film’s car-chase footage was shot with a biscuit car driven by Robert Nagle, but in Borrego Springs, the filmmakers used an arm car equipped with an Allan Padelford Edge Crane System, driven by Padelford himself. “That stretch of hills was really great when we were shooting wide-angle,” notes Bauman. “We also had another car with an ‘elevator rig’ that could raise the camera up and down and get very low to the ground; it could be down right behind the car, and the operator could bring it up, go over the top of the car and come down again.” Referring to a previous gaffing job, he notes, “We also used that on Ford v Ferrari [shot by Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC; AC Dec. ’19].

Bauman adds, “The challenge was the reliability of the VistaVision cameras. You’re banging those things around, and there would be times when they would jam and you’d have to do it again. And there would be times when you didn’t know how much you’d gotten before the camera jammed. But we set up our cameras and ran them out there, constantly changing the exposure as the sun was getting lower. It was all about embracing the raw energy of the moment, and that included embracing the sun bouncing around and directly hitting faces.”

One of the car sequences required a distorted close-up of a shotgun blast, but balancing the exposure proved very difficult. “We had to hide some lights inside the car,” Bauman explains. “The interior was just insanely bright because the ambient light outside was so hot. We thought we might have to use windows in post to help balance those shots, but Justin was able to put a diffused Vortex4 on the floor of the car’s passenger side, and we developed ratios to help strike a balance between the interior, the actors’ faces and the exterior.”

“31 Flavors”

In select urban markets, One Battle is being exhibited in 70mm Imax and in VistaVision, with updated 8-perf horizontal film projectors facilitating the latter format. This was Anderson’s plan from the beginning. During prep, Warner Bros. provided a VistaVision projector so the filmmakers could screen a reel of North by Northwest in the format, and the production took the projector along to screen VistaVision dailies on set.

Bauman notes that watching print dailies is an essential aspect of every film with Anderson. “The rigging grips worked with postproduction to create a mobile projection booth that had two Super 35 projectors and the VistaVision projector. Usually at the crew hotel, a conference space was converted into a screening room so we could view print dailies at the end of every shooting day. Fotokem did all of our dailies and processing.

“We shot almost a million-and-a-half feet of film,” Bauman adds. “We shot with all four of Kodak’s Vision3 stocks, but predominantly with 5219. We would push a stop but rate the stock at 640 or 800, and a 2-stop push would be rated at 1,600. We also pushed 5203 and 5207.

“It was a lot of fun, but it was hard — just a lot of extreme conditions. But with Paul, you’re always pushing yourself. It’s just a huge level of kinetic energy. We’d shoot till absolutely last light to try and get anything in the sky we could, just to get some sort of silhouette, some sort of detail, even if we were pushing 1 or 2 stops. But I think this is going to be an event film. With all these different formats, it’ll be like 31 flavors.”

Tech Specs

Aspect Ratios | 1.50:1 (VistaVision), 1.43:1 (Imax 70mm), 1.90:1 (digital Imax), 2.20:1 (Standard 70mm), 1.85:1 (pillarboxed within 2.20:1 frame)

Format | 8-perf 35mm

Cameras | Beaumont VistaVision, Panavision Millennium XL2

Lenses | Panavision Super Speed, Ultra Speed, Primo, PVintage, prototype VistaVision primes, Standard Speed, Ultra Speed Telephoto, System 65, 65 Vintage, Primo Zoom, VA Zoom; Zeiss Jena Biometar; Pathe Goerz; Heliar; Nikon Telephoto; Canon Telephoto

Film Stocks | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, 250D 5207, 200T 5213, 50D 5203

Unconventional Methods

One Battle After Another is my sixth collaboration with PTA, and one thing I have come to understand and admire is that we very seldom do anything in a standard or conventional way. A good example would be The Master, where we initially were only going to do specific scenes in 65mm, with the majority shot in 35mm. Within a week of starting principal photography, PTA fell so in love with the look of the 65mm that we ended up shooting almost the entire film in that format. Those cameras had been sitting unused on the shelves at Panavision for about 20 years — so, naturally, we had tremendous issues during filming to keep them running, but the final result made the effort so worthwhile.

On One Battle After Another, PTA decided to use VistaVision cameras that hadn’t been used for a full motion picture since the early 1960s. We settled on three bodies, and Giovanni Ribisi’s lovingly restored Beaucam became the A camera, with two additional bodies supplied by the Geo Film Group. 1st AC Sergius Nafa spent months at Panavision getting them battle-ready. Even though he performed miracles, we still had issues trying to run the 1,000' mags without them jamming at about 800' because of the load. Looking through the eyepiece was also a challenge for me, because it’s mounted on top of the camera with the horizontally mounted magazine under it. As a result, almost every shot that was above knee height required standing on a ladder or a platform on the dolly to be able to look down into the eyepiece.

Steadicam also presented a unique challenge because of the horizontally mounted magazine. As the film runs through the camera, a huge weight redistribution is taking place from right to left, which then has to be counteracted by mounting a traveling weight, synchronized to the motor, that travels left to right, allowing the Steadicam to remain balanced to a certain degree. We had discovered this traveling-weight device years ago when we used it on the short film Anima[2019], which was also shot in VistaVision using the Steadicam, and we tracked it down again for this movie. PTA is known for doing extended takes, and a lot of them are on Steadicam, so this became a vital piece of equipment — along with the Volt, which replaces the regular gimbal on the Steadicam and introduces roll stabilization.

It was such a thrill to shoot this film on VistaVision. The last full motion picture shot in this format was One-Eyed Jacks [1961, directed by Marlon Brando and shot by Charles Lang, ASC], so being part of this resurrection was a huge privilege. The quality is truly astounding, and although PTA and Mike Bauman introduced a layer of grittiness to the image, the format and quality still allow for a high-quality 70mm blowup.

A few of the many ways this format enhanced the film for me:

There’s a scene in which Lockjaw hands Willa over to the bounty hunter Avanti [Eric Schweig] in the desert outside Borrego Springs. The backdrop is a wall of rock stretching from one side of the frame to the other, with their cars bookending either side of the frame. It’s an incredibly wide shot, and the actors are extremely small in frame as they walk toward each other and meet in the center. It evokes images from Lawrence of Arabia and the classic Westerns we grew up with.

The final three car chases also benefitted hugely from the VistaVision format, as they feature a lot of verticality. The terrain with the steep hills and dips fits into the 1.50:1 aspect ratio in a far more pleasing way than it would in 2.39:1, for example. I was also framing for 1.43:1 Imax and 1.90:1 Imax, so there were a lot of lines on the ground glass to consider!

One operating challenge during the final car chase was trying to anticipate where the road and the cars were as we were traveling. The camera was mounted on an Arm Car equipped with a Padelford Edge Arm system, expertly driven at high speed by the owner of the company, Allan Padelford, who’s an industry legend. Every time we came out of a dip and over a hill, I was momentarily unsighted as to where the road or the cars were. I tried to memorize the road and which rise would lead to a slight left or right turn, but I found that to be a huge challenge, to say the least. At times during the pursuit, we also used really long lenses, which meant trying to anticipate a car appearing over a rise that was three or four hills away.

The car mounts we used for the French 75 bank-robbery escape made for an incredibly intense sequence. PTA had mentioned The French Connection as a reference, and we hard-mounted a VistaVision camera on the front of a Subaru driven by Allan. We mounted the camera about two feet off the ground, and Allan pursued the picture car at high speed while it was making its escape. By hard-mounting the camera, we achieved a raw, visceral feeling that lends itself to the urgency of the chase. What struck me as different was the old-school, low-tech approach PTA leans toward, as opposed to using a remote head and panning with the picture car wherever it went.

In keeping with this low-tech approach, PTA embraces the use of ride-on cranes like the Titan, which we used on the film, and eschews the modern telescoping cranes and remote heads more commonly used today. He says he prefers an operator to look through the eyepiece. Being old-school myself, I am happy to oblige.

— By camera operator Colin Anderson, as told to Bill Desowitz