Accelerated Evolution

Experts in production and post discuss advances in technology and perspective in the age of Covid-19 and beyond.

Covid21

By Mat Beck, ASC

Everything was in place for the first day of shooting. The virtual-production volume was set up with LED walls, and the pre-rendered assets were loaded in. The Covid protocols were all established. No more than 10 people on set at one time. Tents and trailers outside for hair, makeup and art department. Only one problem — the director of photography had just found out he’d been exposed to the virus. Though he had no symptoms, the production took the most cautious route. He could not come on set. (So much for cinematic immunity!) A new protocol therefore emerged. He watched takes via videoconferencing, and called in comments to the line producer — who transferred the comments via walkie-talkie to the AD, who passed them along to the director and crew. The work continued, and the schedule was maintained.

You may remember the word “homeostasis” from biology class. It refers to the effort of any system — living or not — to maintain a steady state as the environment changes. There’s a slightly newer and somewhat more elegant term: “homeorhesis.” This is the tendency of a system that is constantly in flux to work toward holding a steady trajectory, rather than a steady state. It’s more apt for living things that are changing but working to maintain consistency of path toward a destination. Either word can be useful to describe the remarkable ability of human beings — and their systems — to make corrections and re-balance in the face of difficulties threatening to knock them off course.

The example above occurred during production of a small independent film. The filmmakers are employing some cutting-edge technology to work in the new environment — and yet, in the end, a good old cellphone proved to be the final piece of the puzzle.

There’s another principle at work, of course. Human beings are about connection. We need contact with other humans and tend to do poorly without it. In an age when multiple forces are conspiring to drive us apart, it’s remarkable how strong and creative the efforts are to bring us back together — and how moving it is when they succeed.

Over the holidays last year, a cinematographer was sitting in a bubble with his daughter, feeling sad and nostalgic about family gatherings they used to have when they all lived closer together — and plague-free. So, on the last night of Hanukkah, they organized an impromptu lighting of the candles with a bunch of cousins from all over the country. Seventeen people met on a Zoom call, some of whom hadn’t talked in years. With the help of technology, scarcity turned into abundance.

The production environment has similarly adapted, and pretty effectively.

“As Homo Cinematogensis continues to adapt to the challenging environment, newer technologies are offering their possibilities.”

Paul Rabwin, vice president of postproduction at ABC Signature Studios, points out that a film set is probably the safest place to be during a pandemic. The varied zones, strict PPE and social-distancing rules, and testing three to five times a week means everybody is likely quite safe. He points out that “remote” is now one of the most important words in all aspects of production, from prep through post. Remote meetings, scouting, viewing, dailies, color correction, editing — all are benefiting from the increasing capability to work via a high-resolution interactive link.

The same priority applies on set — existing technologies like remote dimmer boards and lens controls, originally designed for efficiency and convenience, are now used to allow crewmembers to be separated from the cast and other crew. Remote heads and even crane arms can serve the same purpose.

Michelle MacLaren, who recently served as an executive producer and director on Coyote for CBS All Access, is now directing In Treatment for HBO. She reports that both of the show’s two cameras are on remote heads, leaving only the dolly grips near the actors. The production has also turned the necessity for remote communication to their advantage. A special headset connected her to cinematographer Steven Fierberg, ASC, as well as the operators, dolly grips, set dresser and DIT. Everyone on line is in sync. It works great, but still it’s not her preference. As much as MacLaren loves the systems that let her and her team work, she adds, “I’d rather be close to the actors, sitting next to the camera.” Fierberg agrees; he was surprised at first by how much he was missing when, while rolling, his only view of the set was through the remote cameras. Neither he nor the operators could see or react to what was happening outside the frame. The headset arrangement helps enormously, but it does leave out some non-verbal emotional information. The link is like “radio instead of cinema.” Fierberg is looking forward to when he can once again walk over to a colleague to give a note. And he misses the hugs.

Rodney Taylor, ASC is working on the Apple TV Plus series Swagger in Virginia. He, the director and the script supervisor all sit at isolated monitors. Most of the crew must watch the shooting through a Wi-Fi link. The gaffer is behind him, separated by a plastic shield. When lighting with stand-ins, he has to extrapolate the look of each face because they are wearing masks. Camera assistants can’t trade tips or gossip around the camera carts because the carts are separated by the prescribed distance. For people who get so much joy from working together with their talented, motivated teammates, the job becomes emotionally harder. It’s that connection thing again; with the masks on, you can’t see your colleagues’ smiles.

But there are compensations. Taylor reports that the set is quieter, more focused. They actually are working more efficiently — with no problem making their days. Also, it’s quicker to get to work, because there always has to be crew parking close by. Self-driving is safer. And, of course, it’s possible for crewmembers to pursue side projects after hours or on weekends — maybe learn a musical instrument — or just save a bunch of money, because where are you going to go and spend it?

MacLaren describes her experience on set as “lovely. People are so grateful to be here, to be working.” Everyone is making an effort to help each other out. The dolly grip sees MacLaren’s goggles fogging from her mask and gives her the best solution to keep them clear. The AD decrees water breaks for cast and crew because no beverages are allowed on set. A huge directors’ email chain trades hints on handling subtle onset challenges. MacLaren is impressed by the massive, and costly, undertaking by the studio that allows them to work safely, and she’s “grateful that we are still able to tell stories.”

As Homo Cinematogensis continues to adapt to the challenging environment, newer technologies are offering their possibilities.

The groundbreaking advances in virtual-production techniques that were introduced to expand the world of the story now can be used to reduce the vulnerability of actors and crew. A large world can be filmed on a small volume with fewer vulnerable people. And those techniques are already migrating to smaller productions.

Director Randal Kleiser is currently working with his brother, VFX supervisor Jeff Kleiser, and Sam Nicholson, ASC’s Stargate Studios on a virtual-production facility that includes both bluescreen and LED-wall volumes. He notes that one silver lining of the virus will be the accelerating introduction of these new VP techniques, but that one complication is staffing. There are a lot of volumes popping up, and all that computing power will require a lot of qualified people controlling it. They don’t have to be on set, but they have to be on the ball.

Having a running background on an LED wall on a VP set means that the camera, as Nicholson points out, “is essentially compositing on a grand scale in real time.” So all department heads — cinematographer, gaffer, grip, and VP and VFX supervisors — have to work together to assure that all the elements assemble as close to perfectly as possible. As Nicholson remarks, “That’s what makes it very challenging yet very exciting on set.”

A bonus of real-time rendering of the background is that its lighting can change in response to foreground action. For instance, a lantern that is tracked in the foreground volume can appropriately illuminate objects in the virtual background as the light source moves — helping to tie the two environments together. And, when it’s time to change camera direction, you don’t have to call crew to move the camera. Just move a mouse and spin the world.

Ultimately, our success depends on finding ways to stay connected, one way or another. Without connection among the crew, a film can never get made. Without connection with an audience, it won’t succeed. What separates movies from live theater has always been that in the cinema, the players are remote, their performance conveyed to us by technology. But still, the audience can be emotionally moved — moved even more when sitting in the dark together.

While Covid has driven so much of society apart, it has also, diabolically, made it harder for us to generate the stories that help bring us closer to each other. But productions and studios are evolving techniques in response to that external challenge. The best storytellers will continue to use talent, goodwill and technology to foster that connection within our crews, between ourselves and the audience, and, one can hope, within the human tribe at large.

Mat Beck, ASC started out shooting personal films and documentary footage, then began designing digital tools for the VFX industry, including likely the first microcomputer motion-control system. Simultaneously, he worked as a camera operator, progressing to cinematographer and VFX supervisor. He founded Entity FX (Los Angeles, Vancouver) in 2002.

Beck has worked on more than 70 feature films, including such notables as Titanic, The Abyss, Moonstruck, both X-Files movies, True Lies, Galaxy Quest, Batman Returns, The Nutty Professor, Into the Wild, Michael Jackson’s This Is It, I Am Number Four, Yogi Bear, Riddick, and Laundromat. He recently finished work on the Netflix feature The Babysitter’s Guide to Monster Hunting and a sizzle reel for Bedrock Productions.

For television, Beck has produced and/or supervised visual effects for more than 50 series, including Godless, The Walking Dead, The Vampire Diaries, The Originals, Mike and Molly, Smallville, Breaking Bad, and The X-Files. HBO productions included Watchmen, The Righteous Gemstones, Curb Your Enthusiasm, True Detective, Getting On, Game of Thrones, Ballers pilot, Six Feet Under, Entourage and Band of Brothers.

Beck has also directed multiple 2nd units on feature and television projects, as well as an episode of Smallville.

He has been nominated for VES and ATAS awards, and has won two Emmy statuettes. He has served on the ASC MITC committee, the VES Board of directors, the AMPAS executive committee, the ATAS Peer Group, and is a member of the DGA.

The following stories details the efforts of creative individuals and companies in dealing with today's production and post challenges.

The Queen’s Gambit: Light Iron and

Remote Color Grade

By Iain Marcks

The hit Netflix miniseries The Queen’s Gambit, photographed by cinematographer Steven Meizler, had just begun its color grade at Light Iron New York when the Covid-19 pandemic forced a near-global shutdown of the film industry.

“For better or worse, the pandemic ignited industry-wide change overnight,” says Katie Fellion, head of business development and workflow strategy for Light Iron, a Panavision company. “Light Iron was founded on the idea that even though the industry might be used to doing it a certain way, we can always adapt.”

The Queen’s Gambit primarily shot in Berlin, where Light Iron dailies colorist Alex Garcia was equipped with an Outpost near-set dailies system and worked out of a satellite office at Cine Plus. Principal photography began with a five-day shoot in Toronto, where local dailies colorist Jacob Doforno worked from the same Colorfront Express Dailies project database that Garcia had created during camera tests in Berlin. “It was as if we were working from the same facility — except we were thousands of miles away from each other,” says Garcia.

Light Iron was already pivoting toward remote workflows with tools like Streambox and T-VIPS when lockdown guidelines went into effect in March. The work-from-home orders impacted final color as well as offline editorial, which rented equipment and space from Light Iron New York. Over a single weekend, Light Iron moved final colorist Steven Bodner and the editing team off-site to continue their work remotely. Bodner was equipped with a 4K HDR setup, including a Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve panel and 50TB of encrypted storage. The production was finished in 4K HDR Dolby Vision using Streambox Chroma+ and Moxion to remotely review the HDR.

Light Iron’s pre-pandemic remote workflows were consolidated around final color correction, with a colorist in one city and the director or cinematographer in another. “It feels like we’ve accomplished more growth and change in the past nine months than in the past nine years,” says Fellion. “We’re moving into an era where the facility is a centralized hub for media, and creatives can tie into that from wherever they are with their own peripherals.”

The company is already rolling out additional remote offline editorial rentals in New York City, with targeted regional expansion planned this year. Light Iron has also begun deploying Outpost RC, which allows a Light Iron dailies colorist to control the complete near-set Outpost system remotely, regardless of geographic distance.

“Remote postproduction is here to stay,” says Fellion. “With a minimum amount of bandwidth, colorists, editors and dailies teams can do their job from anywhere in the world, reducing the amount of people on set or in the office — a requirement in the era of Covid — while still achieving a fast turnaround. And as we get better connectivity — like with rollout of 5G — more doors will open.”

Looking ahead, Fellion predicts that postproduction will evolve a hybrid approach as clients return to facilities for the control they offer with calibrated environments, as opposed to the kitchen counters and home offices where cinematographers and directors have recently been reviewing color decisions.

In the meantime, “we enjoy exploring new technologies and how they can give us better collaborations,” says Fellion. “The hardest part is that we have had to reinvent ourselves every 24 hours as more technologies are invented. Let’s see what happens in the next six months.”

Arri, Inc. Integrates Advances

By Noah Kadner

As a leading manufacturer of camera, lenses and lighting equipment, Arri has long had a vested interest in virtual production. Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS; Barry “Baz” Idoine; Matthew Jensen, ASC; and David Klein, ASC have used Alexa LF cameras on the trailblazing Disney Plus production The Mandalorian (AC Feb. ’20) to capture in-camera visual-effects scenery on LED-wall volumes. Arri lighting offers remote-control capabilities via DMX and wireless protocols, which can be synchronized to virtual sets and remotely operated. Recently, Arri installed LED-volume stages at its facilities in Burbank, Calif.; Germany; and the U.K. to assist with R&D efforts.

“We see advantages in this transformation of the creative process because it incorporates our cameras and lights into an integrated solution,” says Glenn Kennel, president and CEO of Arri, Inc., and an ASC associate. “We’re always tracking early adopters, and we have supported ILM with the setup and operation of The Mandalorian, but Covid really amplified interest in virtual production.”

ASC associate Stephan Ukas-Bradley, vice president of strategic business development and technical marketing for Arri, Inc., adds, “The stage in Burbank has a 25-foot curved LED wall with two 8-foot sidewalls and is 15 feet tall. The screens are all on risers with casters, so we can move them around and be flexible. The stage is not intended as a commercial-use facility, but rather to engage with creatives to demonstrate the power of this way of working. With the stages in Europe, we can compare notes with productions in different regions to see where the bottlenecks are and hopefully address them to make everything easier, more cost-effective, and better to work with.”

Arri has also worked to raise awareness of its products’ remote capabilities, which facilitate smaller, dispersed crews. Kennel explains that once equipment is set up at a location and connected to a secure network, the visual-effects supervisor can direct, load images and control the camera remotely. Arri’s Camera Access Protocol offers developers in its Partner Program the ability to control many aspects of Arri cameras via an internet connection or over a bonded cellular network. “We also have to ensure that the proper security is provided before remote workflows can be fully enabled in this environment,” Kennel says. “Content producers and studios are rightfully very concerned about the security of their images.”

“It takes a team of experts to make LED-wall cinematography techniques work effectively,” Kennel adds, “and we’d like to help make it simpler, more integrated and easier to set up, with more people trained so that it can be supported as a standard aspect of production. You also have to think a bit differently about how the budget is partitioned, with more money in the previs and front end and less in the back end.”

Adds Ukas-Bradley, “The expense of the LED screens and the technical support they require can be cost-prohibitive to some budgets. It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, but it’s here to stay because people just love the creative possibilities.”

Lux Machina’s Insights and Improvements

By Noah Kadner

Consulting company Lux Machina specializes in virtual production and has provided LED screens and the infrastructure (stage and crew supervision and operation) to drive real-time visual effects through them for live broadcasts including the Academy and Emmy Awards; features such as Oblivion, Rogue One and Solo; and series like The Mandalorian.

“We’ve done three or four full-production LED-wall shoots during Covid to great success,” says co-CEO Philip Galler. “One of the new avenues [we’re pursuing] is working with technology companies on LED volumes to help them solve R&D goals. People assume what LED in-camera can and can’t do, or how easy or hard it is to set up, or what it might cost. So we spend a good chunk of our time on education and walking people through the entire process.”

Galler notes that the pandemic has led to unexpected insights and improvements across the industry. “Changes have finally happened that we’ve been asking for for years from our manufacturers, such as HDR and high frame rate that are more important to film production than to live broadcast,” he says. “Nobody wanted to pay much attention to them until this was the only thing they could do for work. In some ways, the crisis led to the development of improved tools.

“There’s also a huge mental-health issue in the industry because people are used to working longer hours than anyone else. This remote situation has forced many of us to look at a healthier life-work balance. People have found ways to adapt and contribute meaningfully to major productions from their homes, and I hope it helps us resolve some of the mental-health issues.

As a result of certain business areas slowing down or stopping altogether, Galler and Lux found other areas of opportunity they might have otherwise ignored. “Maybe the biggest takeaway from this situation is that we’re seen as high-profile/high-standard, and that level isn’t necessary for every client,” says Galler. “We have modest studio clients now, and we’re finding ways to make sure that they have successful productions. They don’t need the results that ILM achieves, but they still need good quality. A year ago, we would have been less inclined toward that area. Now we’re there not necessarily because we’re hurting for business, but because helping to educate the industry is important.”

Remote collaboration is another area Lux saw greatly expand during the pandemic. “When we scale our business, we used to focus on where someone was located, but it should be more about what people can deliver and letting the quality of their work speak for itself,” Galler says.

Galler also believes other lessons and workflows mandated by the pandemic are likely to persist once the crisis ends. “We’ll continue to have significantly more remote collaboration,” he says. “We’ll see more remote directors, artists and operators, especially as the crisis drags on and more people become accustomed to working remotely. In some cases, being in situ and collaborating is valuable, and some people will push back due to fear of change in the workplace. But we’re looking at a global expansion of the artists and supervisors able to remotely contribute. “A few years ago,” Galler adds, “I’d have said some roles can never be remote, but now I feel we’ve learned that there’s no real reason to go back to the old ways of doing things.”

Mels Studios Pivots to Virtual Production

By Noah Kadner

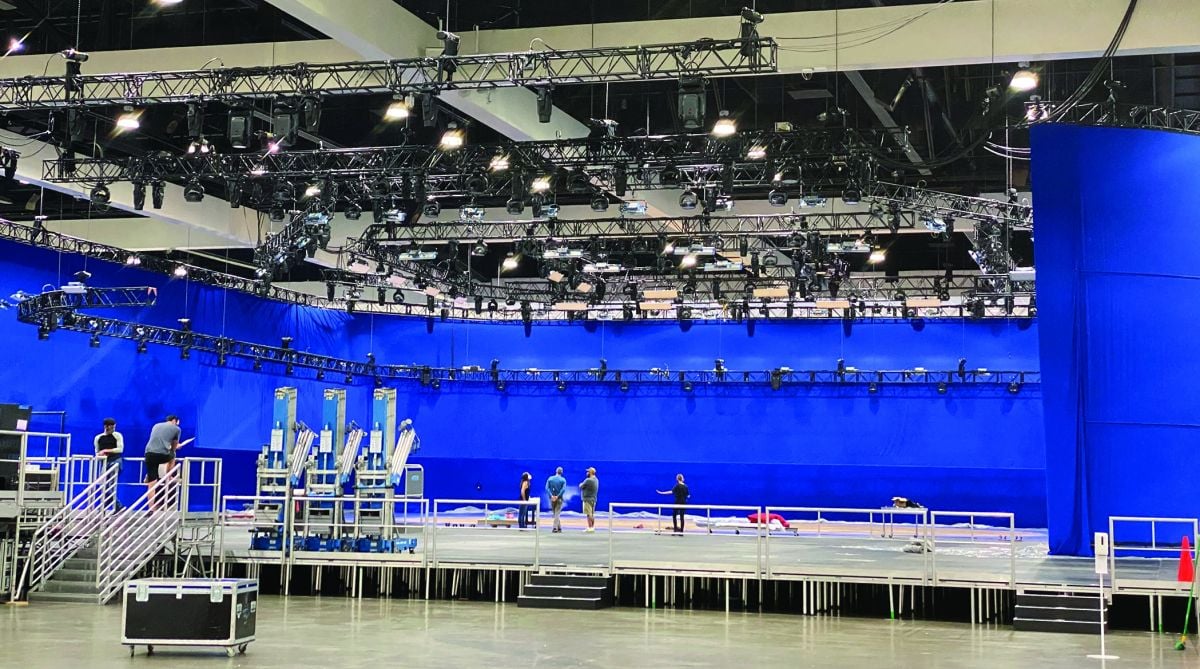

When initially faced with the new safety requirements and protocols, Mels Studios and Post-Production — located near downtown Montreal, Canada — found itself with much of its regular production business significantly reduced or stopped entirely. So Mels looked for creative ways to pivot.

In October 2020, the studio opened a virtual-production LED-wall stage for in-camera visual effects. Mels President Martin Carrier, who has a background in video games, spearheaded the effort to embrace this new filmmaking methodology. “Even before the health crisis, I saw a lot of potential in real-time game-engine technologies, like Epic Games’ Unreal Engine, to bring content to life for filmmaking in a very dynamic way,” says Carrier. “We have a camera department, postproduction and visual-effects teams. Virtual production is the initiative that binds all these disciplines together.”

Mels collaborated with Epic Games, as well as with Solotech, a Canadian event-lighting and staging company that supplied the Absen M2.9 2.9mm LED panels. Mels started with a proof-of-concept rooftop scene and quickly moved on to iterate larger versions of their LED volume. “This technology suddenly opens the door to shoot more exotic locales that would be too cost-prohibitive to achieve any other way,” Carrier says. “It unlocks more creativity on the scripting side.”

Mels offers its virtual production as a turnkey service and can also integrate outside vendors into their real-time pipeline. “One of the main challenges for producers new to LED wall in-camera visual effects is the significant preparation that must be done before shooting,” Carrier says. “It’s well worth the inversion compared to traditional visual effects, because once you’re on set and shooting, you and your DP can see exactly what you’re getting in-camera — as opposed to waiting months for postproduction to kick in.”

Because an LED wall can — virtually — transport a much more modest crew to any location on the planet and beyond without any travel, it addresses many concerns around production during the pandemic. When considering if interest in LED walls and in-camera visual effects will diminish once the pandemic finally ends, Carrier suggests Mels is all in for good. “A DP we recently worked with in the [virtual-production] volume said, ‘At the end of the day, I can see exactly how each shot is going to look, which I would never get on a greenscreen.’ It’s tough to go back to the past because artists put their signature on their work and they want to have confidence in the image.”

Carrier notes technical complexity as a drawback to the process. “In-camera visual effects is like a Formula One racecar: it’s shiny and goes incredibly fast, but the guys changing the tires are not your average corner mechanics,” he says. “You’re dealing with the pixel pitch from many different LED manufacturers, [and with] image processors, lenses, cameras, tracking systems, the ‘brain bar’ running the engine, et cetera. It’s many layers that can potentially compound the complexity. As we’ve worked our way through different iterations of this workflow during the past months, we feel like we’ve gone from junior high to college.

“There’s also complexity to the vocabulary when you have crews coming from the very different worlds of game-engine technology and filmmaking. We have to work all that out as we go. Finally, there’s the challenge of finding the right asset vendors. They have to know how to make assets optimized for the engine and the LED screen itself. In the end, everything is complex, but it’s also very exciting. We’re making good headway and achieving a robust solution.”

Brompton Technology: Remote But Controlled

By Noah Kadner

Brompton Technology develops and manufactures video-processing products for live events, broadcast and film. Video processing plays a critical role in LED-wall virtual production by providing the bridge between the engine that renders game-engine footage in real-time and the LED wall, which displays the footage to then be captured in-camera.

Brompton’s global team includes Los Angeles-based regional technical manager Sean Sheridan and U.K.-based technical solutions manager Adam Callaway, who are integral to the company’s virtual-production efforts and have worked steadily with customers during the pandemic. “Covid has had a massive effect on the positive trajectory of virtual production,” says Callaway.

He notes some features of Brompton processors are essential to cinematographers during virtual production: “Dynamic Calibration gives users a readout of a panel’s capable color gamut and also displays whether a given LED panel can hit the required color targets on a pixel-by-pixel, frame-by-frame basis. Color accuracy is another area that’s critical in VP workflows, as visual-effects supervisors and cinematographers require the LED screens to faithfully reproduce the content that’s been created. This comes into its own when working with HDR content that has been encoded with metadata that needs to be adhered to. While this is useful to our customers in live events, it’s far more critical to the film sector, where the VFX team might be up at the screen with spectroradiometers measuring the precise color being emitted by the LEDs.

“As we’re a tech company, we quickly found solutions to continue supporting our customers in the pandemic,” Calloway continues. “A prime example is that we now run training sessions on our processor features completely virtually. We have a remote studio station setup in London that our technical team can access from anywhere in the world. For example, Sean can control it from L.A. and give a demo to someone in Australia.

“Camera testing can be challenging to do in a completely remote environment, but this allows us to attend camera tests remotely, which means we have zero impact on a production’s Covid-safe ways of working on set. It has changed the way we operate and created new challenges, but we’ve risen to the occasion.”

Adds Sheridan, “It’s been more of a shift in mindset to support the new VP and film markets. We expect that work to continue as LED screens are increasingly chosen for this application, but we also hope to see our other business areas return.

Although Brompton is weathering the pandemic well, many of its customers are rental houses whose business models have been severely affected; consequently, they have pivoted to using their resources in other industries, including virtual production. “There’s been a lot of unpredictability over the last year,” concludes Callaway. “But it’s gratifying to see ingenuity coming to the fore, to see this new industry thriving, and to know that our processing features are being chosen for their ability to enhance the VP experience.”

DNeg and Dimension Studio Extend Reality

By Iain Marcks

In early 2020, visual-effects supervisor Paul Franklin (Interstellar, Inception, The Dark Knight), co-founder and creative director of DNeg, began work on a short feature that he intended to direct as an immersive, extended-reality experience. Through the U.K. nonprofit Digital Catapult — a government agency for the early adoption of advanced digital technologies — he connected with Dimension Studio’s joint managing director Steve Jelley, who helped Franklin develop the project as a virtual production using Epic Games’ Unreal Engine and LED-volume technology, with Dimension Studio acting as a virtual art department and managing the real-time on-set workflows in collaboration with DNeg’s own virtual-production team.

To Franklin, the partnership seemed like a natural fit. “Dimension has masses of practical, hands-on experience in putting things together for live performance and virtual reality,” he says. “DNeg has experience in making sure the digital content is fit for production, and that the color science, the cameras and the lenses are all working in concert.”

At the heart of Franklin’s production is the idea of blending two different locations: an interior physical set and a wide-open landscape. “Virtual production allows me to do this on set with LED-volume technology, and the benefit of doing it that way is that the cast gets to see the visual effects with their own eyes,” he says. “It impacts the way you shoot, and it impacts their performances.”

A technology demo — supported by Dimension, Arri (cameras), Mo-Sys (camera tracking), 80Six (digital workflow), and Roe Visual and Brompton Technologies (LED volumes) — was scheduled for June 2020 at Malcolm Ryan Studios in London so Franklin and his producers could familiarize themselves with the opportunities and limitations of the virtual-production process.

“Over the course of five days, we learned the pipeline for camera tracking, real-time rendering, getting the graphics up on the screens, and understanding how the screens display those graphics when you’re filming — dealing with moiré patterns and luminance levels,” Franklin says.

On the basis of that test, Franklin decided to move forward with virtual production for his project. “I look at these things with my visual-effects sensibility, and the process of producing our film for XR opened up all these story possibilities that weren’t in the original treatment, but lent themselves to the possibilities of virtual production,” he says. “Once you bring something into the computer, it becomes infinitely plastic, and you can start doing the most extraordinary things with it.”

XD Motion’s Robotics Aid Adherence

By Rubis Allouet, Marketing Assistant, XD Motion, France

The use of robots to shoot television shows is an excellent response to the constraints caused by Covid-19. Our most popular solution right now is the Arcam robotic camera system and its software, IO.BOT. Recently, we “teleported” a TV presenter from a Paris studio to a set in Toulouse to co-present a demo program while using 3D objects. To accomplish this, we used two Arcam robotic cameras, one in Paris and one in Toulouse, and both were remote-controlled from Toulouse. The solution includes several camera-tracking technologies, each feeding into a real-time 3D graphics engine to generate the augmented-reality effect.

In short, the Arcam captures the journalist against a greenscreen, keys the image, and sends it to the destination studio in real time, where the 3D elements are added. A second camera synchronizes the images and elements together to create a realistic virtual environment. The data is transmitted over 4G and 5G networks. This is one of our great strengths: we have contracts with all existing telecom operators.

The six axes of Arcam robotic-arm technology make it extremely stable and maneuverable. We can repeat identical movements with perfect regularity and can quickly and easily program new ones at will.

Our Arcam technology helps to overcome the problem of social distancing, which creates issues for studios and production companies that can permit no more than five people on a shoot. The robots are able to carry out the same tasks as the operators without transmitting or being susceptible to the virus.

This, of course, does not mean we are going to replace the operators with robots. On the contrary, we’re moving the operators to a dedicated room, and allowing them to work through the robots they control and program remotely. The teleportation effect can be applied to many different kinds of programs (whether interviews or investigations) by allowing the subject to be filmed despite prohibitions on gathering or moving around in working conditions that respect the law.

Covid forced us to push our solution to the media, and thanks to these robots, they can continue to maintain their activity in spite of the ongoing restrictions and the drop in staff and funding.

TRP Worldwide on the Benefits of Blue- and Greenscreens

By Pat Caputo, ASC associate member and founder of TRP Worldwide

Prior to the pandemic, demand was astronomical. January and February 2020 were our best months ever, and at that point we were expecting a banner year — until the industry hit a brick wall. By the end of the year, things turned around, with loads of blue- and greenscreen being used. Due to Covid, we found that large live events are putting their subjects in front of blue- or greenscreen so they don’t have to be in the same room with an audience. There’s just a small crew and some lighting specialists.

[During the pandemic, productions are shooting] more on stages in a controlled environment — a lot of it against blue- and greenscreen. LED walls are sometimes used, but that’s an expensive way of doing things. Keying fabrics are more cost-effective.

We’re used to doing intricate, custom projects. With the inquiries we receive, there’s no telling what shape or size the customer will need. Whatever it is, we can do it — that’s the norm for us. We specialize not only in keying fabrics, but also in light-manipulating materials: diffusers, bounces, controllers, color correctors and accessories for LED fixtures like our Snapbags and Snapgrids. Ultimately, we try to understand the needs of our customers and develop the right tools to help them.

We hope our friends, colleagues and customers stay healthy during these unusual times.