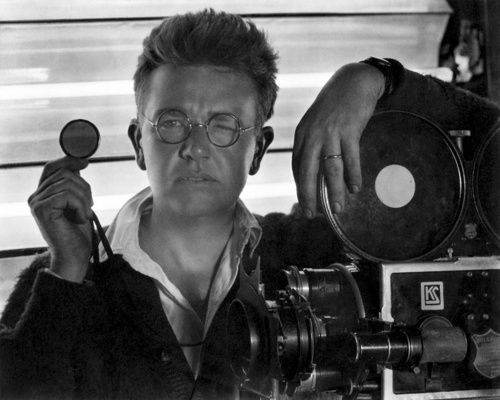

Aces of the Camera: Karl Struss, ASC

From commercial still photographer to the first-ever Oscar-winner for Best Cinematography.

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article originally appeared in AC June 1941.

Director of photography Karl Struss, ASC has the gift of an insatiably inquiring mind. He is never satisfied until he knows, from personal experience, the why and wherefore of things. If you tell him that a thing is impossible, or that it must be done so, because it always has been, he probably won’t argue with you, but he almost certainly will devote his spare time to experimenting with the idea until, one way or the other, he has proven it to his own satisfaction.

That inquiring mind of his has been responsible for a lot of useful things in photography. More than 25 years ago, for example, as one of the nation’s foremost commercial still photographers, Karl decided he wanted a soft-focus lens of a certain quality that lensmakers told him was impossible. Far from being discouraged, Karl tackled the problem himself, experimenting with every possible optical combination until finally he got the result he wanted — a soft-focus lens which at the same time provided a foundation of an essentially sharp image. And today, more than two decades later, one of the world’s most famous lensmaking firms still lists the Struss Pictorial Lens among its finest products.

Later, as a U.S. Army photographer during the last war, Struss advocated the idea of using natural-color photography as a means of seeing through camouflage. His superiors were less farsighted — but today, so we understand, aerial color-photography is one of the “latest developments” in penetrating camouflage!

A decade ago, firmly established as one of the “greats” of the cine-camera profession, Karl felt the need of a certain type of lamp with which to get a soft, yet characterful and controllable lighting on the face of the star he was photographing. No such lamp existed then — but it does now. Karl’s “Lupe,” a funnel-shaped, focusing reflector carrying a tubular, 1,000-watt frosted globe and mounted on a multi-jointed arm so it can be placed in any conceivable position, has become a universally popular instrument for face lighting.

Another important cinematic development for which Struss’ fondness for private photographic experimentation is responsible is the trick, used in such widely differing productions as musicals and horror films, of transforming a normal-appearing makeup by means of carefully coordinated makeup and filtering. The trick, once you know of it, is simplicity itself: use a long graduated filter shading from red in one end to an absolutely complementary green at the other. Then make up your actors’ faces with cosmetics which when viewed through one end of the filter — say the red end, photograph white, while through the complementary-colored green filter, they will photograph black. The amazing change is made with no more effort on the part of the camera-crew than sliding the long filter across the lens!

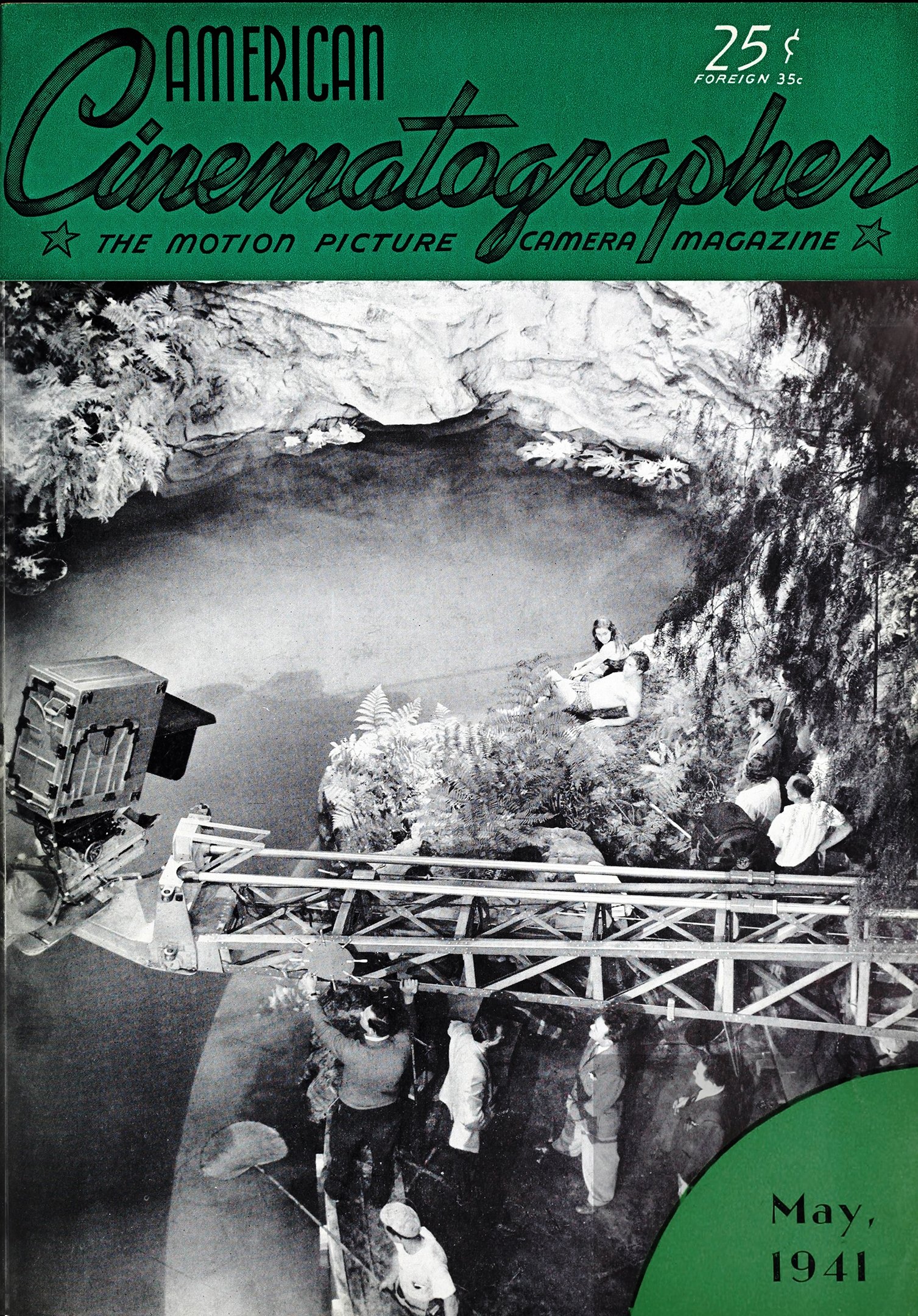

As a matter of fact, Karl considers a scene in his present film, Paramount’s Technicolored Aloma of the South Seas, as far more difficult than these filtered trick-shots. The scene begins with Aloma, as a child, sitting beside a lagoon and singing. The camera dollies up to her, around and down to show her reflection in the still pool. A nut drops into the pool, breaking up the reflection. When the water quiets down, Aloma, now grown to womanhood and played by Dorothy Lamour, is mirrored in the water. And to close the scene, the camera dollies back again on its previous course — up, around and back.

“Lighting in Technicolor can be done with almost the same freedom as in black-and-white, though in a slightly higher key.”

Doing this in synchronism to pre-scored music, with the lighting complications of a big stage-built exterior set, and the added physical handicap of the big and somewhat unwieldy Technicolor three-film camera made that, in Struss’ estimation, the most difficult single scene in his 22-year career as a cinematographer.

During that career, which has run the cinematic gamut from the old-time ortho-film “flickers” to today’s Technicolor, Karl Struss has proven himself not only a technician par excellence, but one of the industry’s most versatile camera artists.

He shares with Charles Rosher, ASC the distinction of being winner of the very first Academy Award for cinematography. That was back in 1927, and the picture was Sunrise, upon which Struss and Rosher collaborated. Twice since he has been in the exclusive circle of Academy Award nominees, and this year, judged at least by the rushes of Aloma — his first in Technicolor, by the way — he bids fair to be strongly in the running for the coveted “Oscar” yet again.

Struss is one cinematographer whose work has never become typed. With the possible exception of westerns, every conceivable type of feature production has flowed through his camera. He has gone from DeMillian spectacle to out-and-out horror melodramas, [Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde] followed, perhaps by a Marx brothers’ comedy, to say nothing of the task which kept him busy most of last year, bringing Chaplin’s The Great Dictator to the screen. And for the many years that Mae West was a name to conjure with at the box-office, she showed her professional wisdom by insisting that she be filmed always through the medium of Struss’ softly sparkling high-key cinematography.

Right now, he is enthusiastic about color. What is more, it and its sponsors like him; he is one of the very few “production” cinematographers qualified, in the opinion of Technicolor’s extremely conservative executives, to take complete and unaided charge of filming a Technicolor production.

Speaking of color, Struss makes light of the supposed technical difficulties of the process. To him, they’re offset by many advantages. “For example,” he points out, “take the matter of making matte-shots. In black-and-white, we go to a lot of trouble matting out the unwanted portions of the scene, so that the matte-painting can be double-exposed in later. In Technicolor, we just shoot the scene ‘as is,’ for Technicolor’s printing matrices are made on the optical printer anyway, and printing in the desired matte-painting is a simple part of what is a routine operation to them.

“Lighting in Technicolor can be done with almost the same freedom as in black-and-white, though in a slightly higher key. In some ways, we’ve an even wider range of tools and effects in color lighting than in monochrome: we have the tremendous range of lamps from the big 170-Amp. arc spotlights down to the little Mazda ‘baby spots.’ And we can play our lightings for color as well as for illumination-contrast. Using the arcs with the straw-colored ‘Y-l’ gelatins on the high-intensity spotlights, and the Inkies with C-P globes and appropriate daylight-blue filters, we have light of a perfect daylight white. Take the filters off the high-intensity arcs, and we have a steely-blue light that is excellent for moonlight effects. Take the filters off the Inkies, and we have a warm-toned light that is ideal for lamplight and similar effects. Put other filters on any of these lamps, and you have a new projected-color effect. The possibilities are endless.

“As a matter of fact, you can learn things in color — especially as regards filtering your light-sources and using modern arcs — that should stand you in good stead in black-and-white. I know this color picture has given me many ideas I want to try out in black-and-white as soon as I have an opportunity to experiment.

“And there’s a point I’d like to bring out strongly. Today, more than ever before, the industry needs photographic experimentation. We have new tools in our hands that open the way to all sorts of valuable new techniques. Coated lenses — super-speed films — improved light-sources—the techniques we can bring over from color to black-and-white: properly combined, they can show us many new effects, and new and more efficient methods. But it demands practical experimentation! And under today’s production conditions, that calls for increased cooperation between the studios and their cinematographers.

“In the past, we have all of us carried on more or less extensive programs of individual experimenting. Today it has become too costly for an individual to do in 35mm, though many of us still do it in 16mm, in so far, at least, as we can be sure of getting parallel results in standard and substandard film.

“I am sure it would pay the industry at large big dividends in better pictures on the screen, and more efficient and economical methods of getting them.”

“But for the final, clinching proofs, we ought to work under actual studio conditions. That is difficult for an individual today. If he is not under contract to a studio, it is difficult to get the necessary cooperation. If he is under contract, his employers usually regard him as too valuable an asset to waste time in that manner, but keep him going from one production to the next with little, if any time between pictures for experimenting.

“It seems to me that now of all times, the industry would benefit if some centralized plan for photo-technical experimentation could be gotten underway. It might be within some studio organization itself; it might be cooperatively managed between the producers as a group and the ASC as a group. But I am sure it would pay the industry at large big dividends in better pictures on the screen, and more efficient and economical methods of getting them.”

Struss, who followed up his Oscar win for Sunrise with two more nominations in 1930s — Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932) and The Sign of the Cross (1934) — racked up a fourth for the aforementioned Aloma of the South Seas (1941), as predicted by AC author Walter Blanchard.

In 1951, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences produced The Cinematographer, an informative short film about the complex role of the director of photography. The star was Struss.

He continued working until 1959, both in film and television. He finished his career with more than 140 credits as director of photography, later ones including 24 episodes of My Friend Flicka, several Tarzan movies, and the original Vincent Price version of The Fly.

He passed away December 16, 1981, living to an enviable age of 95. The year before his death, he won a Silver Medallion Award at the Telluride Film Festival for "recognition of achievements in the film industry."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.