Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans — Lauding A Landmark

The classic film, which earned ASC members Charles Rosher and Karl Struss the first Oscar for Best Cinematography, has inspired filmmakers around the world.

Ed. Note: 40 years ago, Almendros was invited to discuss a film of his choosing at the University of Ohio as part of the Academy Visiting Artists series. He chose Sunrise. This transcript of his talk was originally published in AC April 1984 and re-published in AC June 2003.

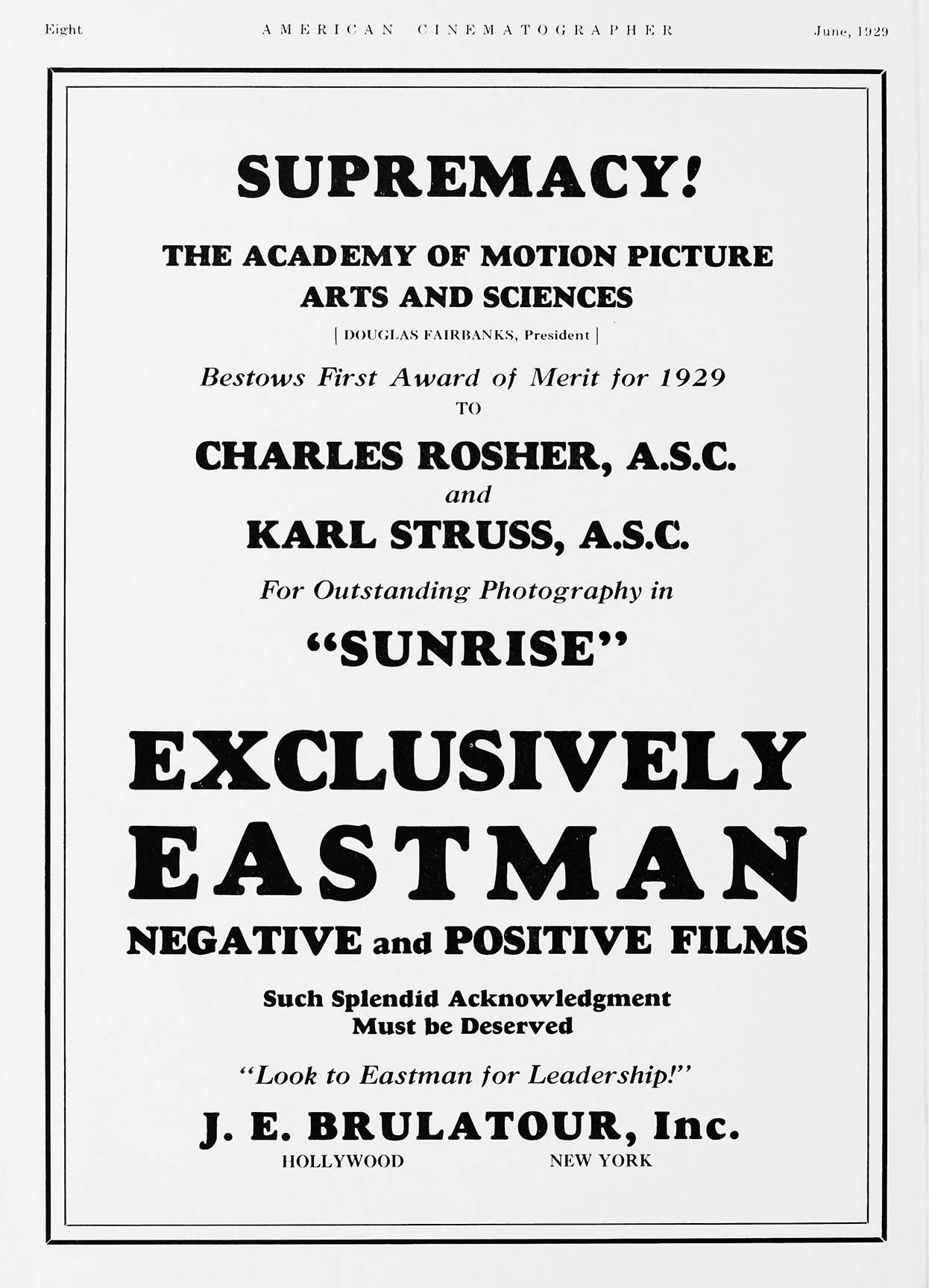

The reason I chose this movie to discuss, aside from the obvious one that I like it very much, is that it received the first Academy Award given for cinematography. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awards were created in 1927, and in that very first year Sunrise won a special award that has never again been given, for "artistic quality of production." Janet Gaynor won the first Oscar for Best Actress in Sunrise, Seventh Heaven and Street Angel; Rochus Gliese was nominated for interior decoration of Sunrise; and that first award for cinematography went to Charles Rosher, ASC and Karl Struss. [Ed. Note: Struss became an ASC member following the film's release.]

As strange as it may sound, awards for cinematography did not exist at that time and, stranger yet, they barely exist today. Cannes, Berlin, Venice and all the other major film festivals of the world have no awards for cinematography. They do have awards for supporting actors and supporting actresses, for writers and directors, and for a lot of other things, but the cinematographer's work is often disregarded. It is to the credit of the Academy to have been the first, to my knowledge, to give awards to us.

According to my research, Sunrise was made because William Fox, head of Fox Film Corporation, had seen a previous film F.W. Murnau directed in Germany called The Last Laugh, with Emil Jannings. Fox wanted prestige for his company, so he told Murnau that if he would come to Hollywood he would give him carte blanche and unlimited funds. It is said that he gave Murnau the final cut and that no one — not even Fox — had the right to watch the rushes except the director himself, the cinematographers and the editor. This may or may not be true. I have the impression, from reading some passages in a book Lotte Eisner wrote about Murnau, that the comedy scene with the pig may have been a concession made to Hollywood, but there is no proof of this. It is true that Carl Mayer, who wrote the script — and had been the screenwriter of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari — did not include the pig sequence or any other comic scenes in his first draft, which Lotte Eisner read, so they probably were added later in Hollywood.

By the way, the script was written in German, and even the sets were already designed in Germany by Rochus Gliese. This is why Sunrise is such a hybrid movie. The city looks like nowhere on earth; one wonders in what country it could be located. The landscape and the people — what are they? American? German? Scandinavian? It doesn't matter, for Sunrise is a fantasy, not realism; there is stylization in every scene, and that hybrid quality contributed to the stylization.

I don't think it was a bad thing that Murnau went to Hollywood, as some have said. He got in Hollywood the technical know-how that did not exist in Europe. The film is crafted exceptionally. The camera movements and the special effects are unbelievably perfect for the time.

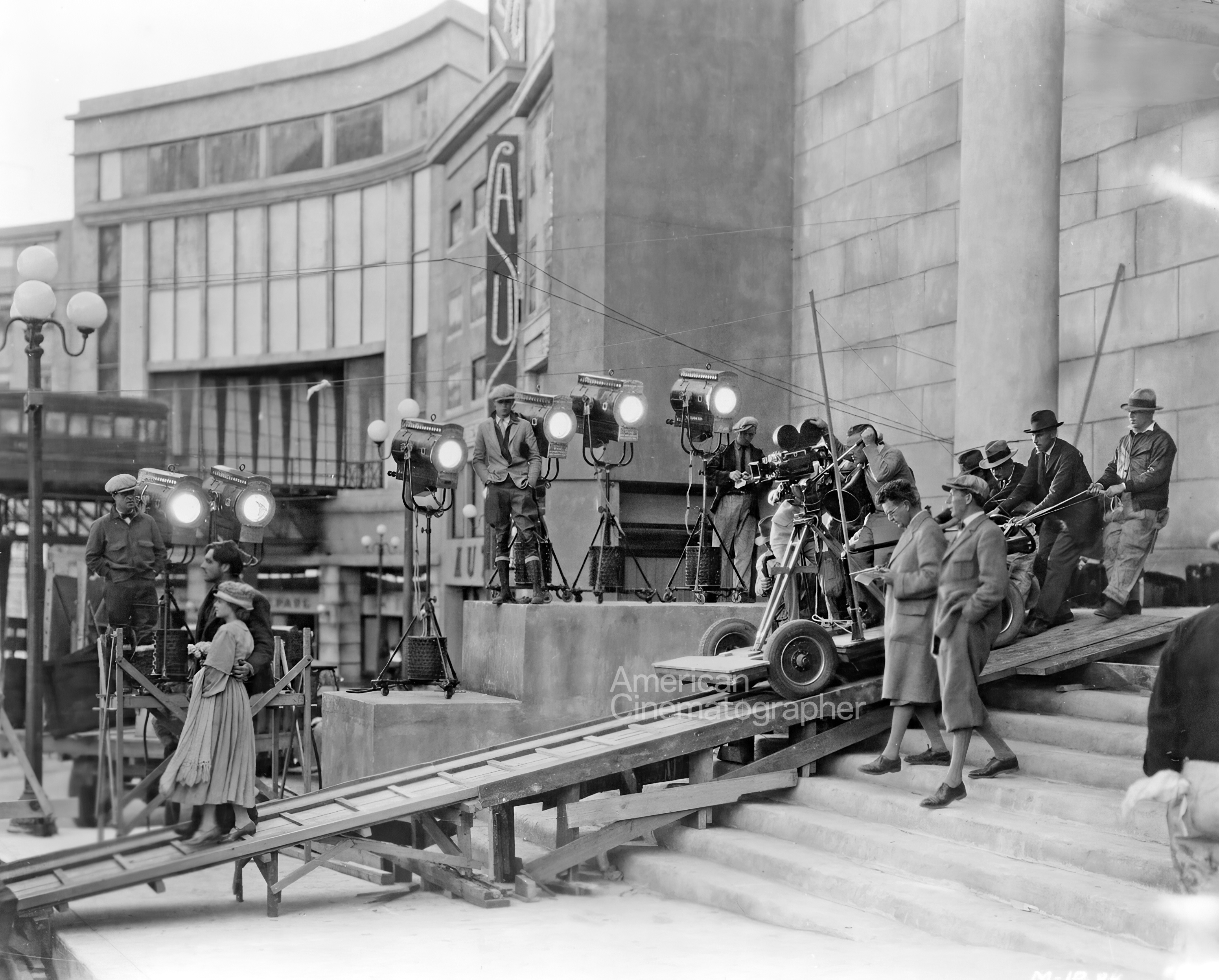

Also, Hollywood allowed Murnau to build the sets for an entire city. Of course, it was built in false perspective. The houses in the background were smaller than those in the foreground to create an impression of depth. In the amusement-park sequence, for example, he used this false perspective very strongly, with children and dwarfs in the background dressed in adult clothes, so that the set would look much deeper than, in fact, it was. This technique was later used a great deal in Hollywood. The interior sets also were designed with trick perspectives. The ceilings, walls and floors were slanted slightly, so that through the camera they appear to be larger and deeper.

According to Charles Rosher, the lenses they had at the time were 55mm and 35mm. The very wide-angle lenses that came later did not exist then. So, in a way, the makers of Sunrise anticipated the coming of wide-angle lenses through set design. They were, of course, influenced by painters who, since the Renaissance, had used the wide-angle, forced-perspective effect often.

The main reason why Fox and the Americans were so amazed by Murnau's work in The Last Laugh, and why they brought him to Hollywood, was what they called the continuous technique of shooting. D.W. Griffith had invented editing, and in silent films there were many cuts in every scene. Murnau, in opposition, pushed to an extreme the idea of the camera moving like a person through a scene. Remember the scene at the beginning of Sunrise in which the hero (George O'Brien) listens to the city woman whistling far away? The camera is him as it goes through the trees and weeds of the swamp, until it gets to the river and meets the woman of the city. All of that scene is in one shot. There are many other scenes like this in Sunrise — long dollies — and that was unusual at the time. That's why Murnau was brought to Hollywood, for this special technique he had developed.

Nevertheless, the makers of Sunrise did not spurn any of the devices of cinematographic language originated by other directors or cinematographers. They made continuous shots, but there is also cross-cutting in the scene in the boat, for instance, and they used a lot of close-ups in many parts of the film. There are a lot of superimpositions — double, triple images. They masked the film partially. In the beginning, when the scenes resemble travel posters, we see simultaneously, in split screen, the boat and the people at the beach. This was done by rewinding the film and shooting the unexposed part again. The technique was like a collage; it was used in many posters at the time.

Murnau belonged to the school of German Expressionism. The camera angles, the lighting, the sets and the costumes were meant to convey the psychological complexities of the characters.

Murnau wanted originally not to use titles in the film — he had made The Last Laugh without titles — but here he gave another concession to Fox. Nevertheless, he used only a few, and at that time of the silent cinema, it was customary to use many more than there are in this movie. Murnau would have preferred to let the images speak without words, by associations of visual ideas or through contrasts, superimpositions and symbolism. The images had to tell the story, not the titles. Murnau said in an interview that he wanted "cinema to be cinema." The other arts — literature, for example — should not intrude, which is why he did not like titles. He wanted stories to be told in cinematic terms.

The compositions give an interesting impression of three dimensions. This was achieved by having objects or people in the foreground and action in the background, as in the scene where the city woman is watching the searchers coming back from the rescue attempt. In the interiors, there are lamps in one part of the frame or, in some instances, statues in the foreground. The foreground objects are cut off by the frame on one side, leaving the rest of the foreground open for the main action, enhancing the impression of depth and perspective. This idea of depth had a great influence on Orson Welles; the transmission, apparently, went indirectly through John Ford. Ford liked Sunrise very much, and that's why he put so much depth in How Green Was My Valley and all the other movies he made during that period of his work. Of course, by the times of John Ford and [ASC members] Gregg Toland and Arthur Miller, wide-angle lenses were available, making it possible to more easily obtain that feeling of depth that previously could be gained only through set design.

Some of the other techniques in this movie that influenced cinema later on were slow motion, flashback (in the scene of the drowning), cross-cutting and back projection. (The backgrounds are always important in Murnau's movies; there's always been movement there, as in that scene of Janet Gaynor and George O'Brien in a restaurant with people dancing in the background.) In Sunrise there are often two actions going on at the same time. In the dream sequence, when the man and wife are walking in the city, suddenly they seem to be in the country, then they come back to themselves because there is a traffic jam, and they again are in the city. This is how it was done: they were walking on a roller (conveyor belt) and behind them was a projected film which included the dissolve from the city to the country, and back to the city. On the other hand, when Gaynor and O'Brien are on the tramway, the opposite was done: we see the actual background.

This technique was virtually abandoned until the French New Wave era; one must wait until Godard to see real moving backgrounds shot from a car, because for years they were all done in the studio. This was because of sound recording and the massiveness of the cameras.

This brings up another subject: the mobility of the camera in Sunrise. Silent cinema reached its peak with this movie and others made in the last years before sound came in, from 1925 to 1929. Silent films had become extremely sophisticated. They were perfection itself, especially in the area of camera movements. The camera was very free then, and this film is one of the best examples. When sound came, because of the huge blimping necessary to blot out the noise of the camera mechanism, the camera became very static and the techniques became stiff and studio-like. So it is a pleasure to see that ride on the tramway and note that the sunlight hits according to the movement; if the train turns, the sunlight shifts as well. The sense of reality in that scene is wonderful.

Another technique used for atmospheric effect was smoke. Smoke nowadays is very much in fashion, as in E.T. and my own Days of Heaven. Everybody is using smoke or fog. As you can see, that is hardly new, either. Remember the swamp scene where you see lots of smoke? And in the marriage scenes, the smoke materializes the light rays coming in from a high church window to create a divine, holy scene.

There are many dolly shots in Sunrise. Some are very well done. I don't think you could make that very first one better today. Rosher and Struss invented the suspended camera dolly over the heads of the players. Apparently, they put tracks on rails on the ceiling (instead of on the floor), as in the scenes in the restaurant. When I first saw Sunrise, I thought they had used a crane dolly, but after reading some articles in old film magazines I learned that it was in fact a suspended camera on a track in the ceiling of the studio.

Backlighting was a typical technique of the time, perhaps more so in this movie than in other silent films. There was a constant use of backlighting that practically designed people and made the smoke materialize when the city woman smoked cigarettes. It was so atmospheric you could almost touch the air and smell it.

Sunrise is a dialectical movie. It obviously was designed by placing things in opposition. The city woman is in black, she's a brunette, and her clothing shines like a snake's skin. The peasant woman is pale and blonde and dresses in light, soft tones. Purity against evil. The territory of the bad woman is the swamps and the river. She acts by moonlight, whereas the good woman acts in sunlight and has farmland, domestic animals and flowers around her. Another major opposition is that of the country vs. the city. In fact, the shooting script was written in a way so that every scene would be repeated in a symmetrical way — symmetrical but opposite. For example, the first ride on the tramway would be unhappy, the second would be happy. In everything you'll find a counterpart.

Q&A DISCUSSION

Student: Two kinds of backgrounds exist in this film, the process background you referred to, to simulate the illusion of walking in the street, and the real background that appeared while they were in the tram. Do you feel this to be an aesthetic contradiction?

Néstor Almendros, ASC: No, because whatever serves the story is good. What counts is not how you do it, but whether you make the audience believe. I don't think there is contradiction on the screen, but [rather] a great unity of style. It is the result that counts.

Which of the two scenes do you find more striking?

Almendros: One always admires what one can't do. I am, I should say, a realistic director of photography. So when I saw that dreamlike city scene, I had to back it up in the projector and play it again. That's how astonished I was. On the other hand, I admire the scene on the tramway because it was advanced for its time and similar to what we do today. I admire both scenes; I'm very eclectic.

What do you think of the amusement-park scene? It's not a real amusement park, but it works so well. Would you do that, make something fake to get your point across?

Almendros: You always stylize things, whether you do it by building sets or shooting in natural locations, though sets are expensive now, and with huge sets today you tend to go to the real thing - like we did with the amusement-park scene in Sophie's Choice, for instance. Now cameras have become very mobile again, and sound is portable, so in the past 20 years it's [been] easy to go back to the locations as Murnau did. It was in the '30s, '40s and '50s that it wasn't possible; they had to do everything in the studio. I think that scene in the amusement park makes Sunrise a true work of art, in the sense that this scene is constructed and imagined by the director entirely. He wanted total creative control, and he got it.

It seems that a tremendous amount of the action in this film is directed toward the camera on diagonals. It seems to be different than the omniscient view in Hollywood photography. Who was responsible for that positioning?

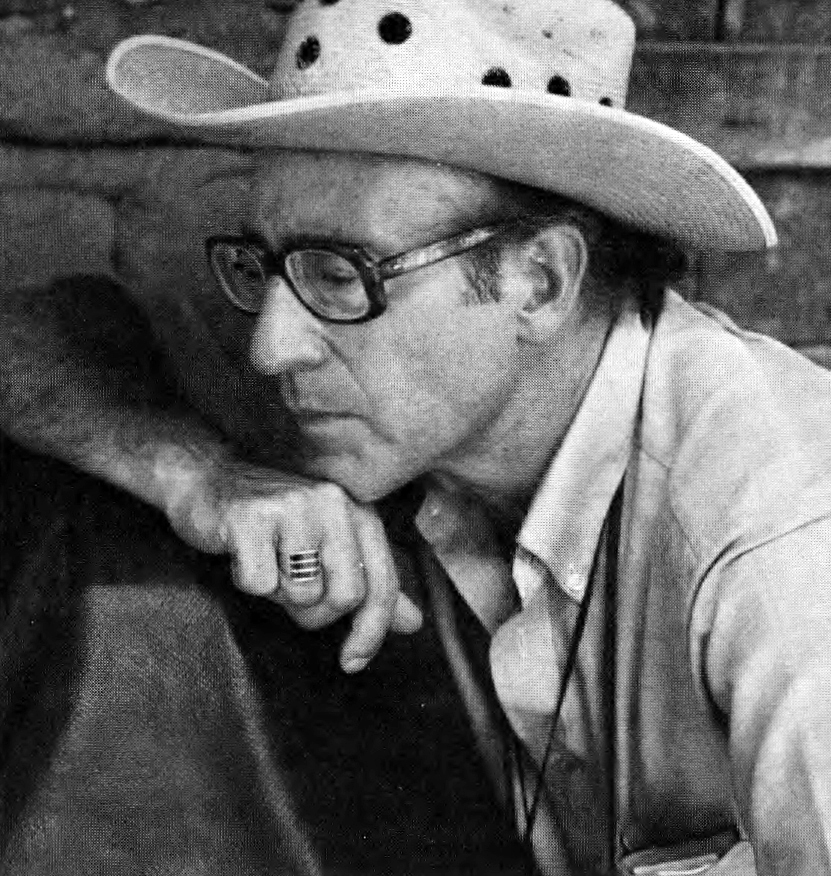

Almendros: I'm glad you noticed those diagonal compositions, because they give the frame dynamics. Knowing Murnau's other films, I'd say Murnau is responsible for it, though I'm sure the cinematographers helped and cooperated, as usually happens. Karl Struss was one of the disciples of Stieglitz — he had been a photographer before he became a cinematographer. That's probably why some of the scenes of the city streets look like Stieglitz. But if Rosher and Struss were influenced by any other photographers, they would certainly have been German. Murnau brought with him a partially German crew. He must have known that Rosher and Struss were the best cinematographers in Hollywood at the time, and that they would be capable of understanding what he wanted.

How was the moonlight effect achieved?

Almendros: I'm sure it was an entirely built and painted set. The reflection of the artificial moon was in real water on the set. There was a strong backlight above the actors off frame, but from the same direction as the moon.

How do you feel this film affected Hollywood?

Almendros: There was a great influence. Think of John Ford's The Informer. Street Scene, directed by King Vidor and photographed by Gregg Toland, also had this influence. The continuous shooting idea was certainly influential to Vidor. When you think of 1927 and then 1935, when films really started moving again, that's less than 10 years. The influence obviously had not vanished. It was only for a moment, with the first years of sound, that the cameras got to be so cumbersome and they weren't so mobile.

How did they do the night scenes, with fast film?

Almendros: They were all lit in the studio so they had control, and it was not a question of lack of light but of contrast. Also, sometimes they could have pushed the film; that was also done. The only defect I see in this film in relationship to films today is the night scene of the search for the drowned body in the river. The lanterns of the searchers hardly give any light, and you can see that they are just props. You can tell the scene has been lit artificially, and it looks false. Allow me to use my own example to illustrate this. In Days of Heaven, the lanterns were actually giving light. Also, because our film was in color, that allowed us to have warm color-temperature tones on the screen to give the impression that the lamps were burning kerosene.

Has the advent of sound made the viewer more aware of narrative and less aware of the visual aspect?

Almendros: Yes and no. At the beginning of sound, certainly, but not later. Music, for instance, enhances the image, and the use of sound might help the image as well. Dialogue, of course, makes the viewer less aware of the visual aspect of film, which is why I favor films with few words, such as Days of Heaven and Wild Child.

A New Dawn for Sunrise

By Rachael K. Bosley (with additional reporting by David Samuelson)

The recent restoration of Sunrise undertaken by 20th Century Fox, the Academy Film Archive and the British Film Institute (BFI) was unique for a number of reasons, not least of which was the ethic that shaped the work from start to finish. Throughout the project, which included the first-ever restoration of the film's Movietone soundtrack, all three parties were determined to treat the 1927 film as the slightly flawed gem that it is. As BFI technical director Joao Oliveria puts it, "Sunrise is like an elegant old lady who should show her age but still retain her dignity."

Sunrise was a big winner at the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929, taking statuettes for cinematography, for lead actress (Janet Gaynor) and for "Most Unique and Artistic Production," an honor that was never awarded again. When the Academy began planning its 75th anniversary celebration, "the stars just aligned," says Schawn Belston, director of film preservation at Fox. "We had been talking with the BFI about collaborating on something; the 75th anniversary of the Academy Awards was around the corner, and Sunrise plays an important role in that; and Fox Home Video had recently started the Studio Classics DVD line, which keys off of Academy Award winners. So suddenly everyone was interested in Sunrise at the same time."

There were at least two original negatives for Sunrise, one for the Movietone version (1.20:1) that was exhibited in the few North American theaters equipped with Fox's patented Movietone sound system, and one for the full-aperture (1.33:1) silent version that was exhibited everywhere else. Both negatives were lost in 1937, when a fire destroyed the New Jersey storage facility that housed Fox's film materials.

When the restoration team began gathering materials last year, the most viable source for their work was determined to be a 1936 diacetate print that had the Movietone track, held by the BFI's National Film and Television Archive. (Fox had a fine-grain master positive that was in worse shape, and the Academy had a safety print from the 1960s.) At an archive in Prague, Oliveria and David Pierce, director of the BFI archive, discovered a full-aperture nitrate print that had been made in 1927, but it was missing almost a reel of footage and featured different camera angles and edits. "Restoring silent movies is always a bit of a conundrum because you're dealing with A- and B-camera negatives, and sometimes C- and D-camera negatives, that are all different," notes Michael Pogorzelski, director of the Academy Film Archive. "The only way to generate more than one negative in those days was to have more than one camera film the action, and the A-camera footage was always intended for the film's home audience. For Sunrise, the European market was the secondary market." The restoration team eventually decided to treat the BFI's diacetate print "as the official version of the film, and fix it up as best we could," says Belston.

Oliveria began by using a wet-gate step contact printer to make a new dupe negative from the 1936 print, sections of which were already deteriorating. "That was the hardest part of the project, and Joao did a brilliant job," Belston remarks. After transferring the Movietone track to digital tape, the BFI shipped the new materials to Los Angeles.

Pogorzelski supervised the restoration of the soundtrack, which was carried out by John Polito at Audio Mechanics in Burbank. "John is very, very good at what he does, and he's very patient," says Pogorzelski. "Sunrise was one of the earliest examples of sound on film, and we all felt it was extremely important that the track be restored to what it sounded like in 1927, warts and all. In the digital realm it's extremely easy to take out anything that sounds like a defect — a pop or hiss or crackle — but depending on the studio and time period, that could actually be what the film sounded like. We wanted to very sure we weren't removing something that had always been there, so we made a transfer of the print onto video with the track area visible, and if we heard something [questionable] we could go back to the picture and determine whether it was an artifact induced by time or wear. If it was, we corrected it. It's an extremely rough track, but it's also very good — those variable-density tracks have such range of frequency response between the very lowest bass and the highest treble. We left in a lot of hiss, a lot of noise floor problems, because that's what Sunrise sounded like in 1927. You can make a 1927 track sound like Jurassic Park if you want to, but that isn't restoration; it's something else."

Maintaining this ethic led the restoration team to leave occasional out-of-sync sound effects out of sync, instead of correcting their timing. The most noticeable example is the night scene in which the Man (George O'Brien) furtively enters a barn and jumps when a horse suddenly kicks over a bucket nearby. As it plays out in the film, the horse actually enters the frame before the sound effect announces the animal's presence and the Man reacts. "That was always out of sync," Pogorzelski says with a smile. "That would be so easy to correct, but it wouldn't be true." (Indeed, in the June 1929 issue of AC, Fox film editor Louis Loeffler wrote about the difficulties of cutting Movietone films and keeping the sound in sync.)

One tricky aspect of restoring the picture involved eliminating the several black frames that preceded and followed every intertitle in the 1936 print. "We're surmising that in order to keep the picture and track in sync whenever they lost picture, they'd just slug at an intertitle to keep the picture the same length as the soundtrack," explains Belston. "We had Cinesite scan the intertitles and digitally duplicate some frames to stretch them out a bit. It was more complicated than we originally anticipated because all of the titles feature some sort of animation; often there's a faint mist floating behind the text, and many of the words themselves are animated."

The rest of the work on the picture was done at YCM Laboratories in Burbank. To augment a few sequences in the new dupe, Belston had YCM copy sections of Fox's fine-grain and build them as B-rolls. He explains, "Our fine-grain is inferior to the 1936 print in terms of quality but is actually more complete. Two sequences in particular, the tracking shot in the swamp and the peasant-dance sequence in the city, play a bit longer in the fine-grain, so in an effort to make the most complete version possible we picked up those sections from our material."

Whereas most film preservationists' work ends with the creation of a new print, Belston and Pogorzelski were able to personally supervise the video transfer of Sunrise, thereby ensuring that home-video audiences would see the same film they had created in the lab. "In doing the transfer, we were very careful to maintain the tonal range of what we'd seen on the diacetate print," says Belston. "It's so easy to make things too clean and too contrasty in telecine, and the beautiful thing about the photography in Sunrise is the beautiful middle range of tones. It's not stark black-and-white; it has a lovely, soft-gray quality. With the beautiful new dupe we had, we could've cranked it up and made it look like Citizen Kane, but that's the last thing we wanted to do."

Pogorzelski, who calls the opportunity to supervise a video transfer "extremely rare" in his line of work, observes, "When the Academy gets involved in a restoration, we're adamant about not trying to turn a film into something that it never was, but one thing that's a little hard to keep control over with the studios is the video transfer and the DVD and TV versions. At almost every studio, the home-video department is an entity unto itself, and it goes to the beat of its own drum; it's therefore hard for us to keep a hand on what the film looks and sounds like in its home-video incarnation. It's painful when you have a print that you've done all this work on, and then the DVD doesn't look remotely like what you did. Thankfully, this is happening less and less; cinematographers are able to supervise the transfers of films they have shot, or restorationists are able to guide the film through the process. The high standards of the DVD audience and DVD collectors help keep a critical eye fixed on these products to ensure they are as good as they can be."

This article was originally published in AC June 2003.

Looking Back

In 2019, to celebrate the ASC’s 100th Anniversary, Turner Classic Movies programmed a slate on films noted for their memorable cinematography. One of them was Sunrise, with ASC member Robert D. Yeoman briefly discussing the project with host Ben Mankiewicz:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.