Terra Incognita: Ad Astra

Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC and director James Gray paint a portrait of souls adrift in deepest space with this sci-fi drama.

Unit photography by François Duhamel, SMPSP. All images courtesy of 20th Century Fox

Photographed by Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC and directed by James Gray, Ad Astra tells the story of Maj. Roy McBride (Brad Pitt), an astronaut who discovers that his father, decorated astronaut H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), whom Roy has long believed to be dead, may in fact be alive — and responsible for a series of cataclysmic dark-matter energy bursts emanating from Neptune.

Decades earlier, Clifford had embarked on a deep-space search for intelligent life as commander of the Lima Project. Clifford’s lifelong absence has made Roy a solitary and remote individual — a perfect candidate for the psychological stresses of space travel, and thus the ideal choice to traverse the solar system and lure Clifford out of hiding. As Gray describes, the film is “Heart of Darkness crossed with the imagery and mood of the Apollo and Mercury missions.”

Ad Astra marks the first collaboration between Gray and van Hoytema. After The Lost City of Z (AC May ’17), cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC — who had also shot The Immigrant (AC April ’14) for Gray — started work on Okja with director Bong Joon-Ho in South Korea. “Darius wasn’t available and I needed to start the conversations for what was going to be a massive technical undertaking, so I went to Hoyte, whose work I’d loved ever since I saw Let the Right One In, and then Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy,” Gray remarks. “Interstellar was just the icing on the cake — proof that he knew the technical ins and outs of doing a space movie.” [Ed. Note: See AC, Dec. ’11 and Dec. ’14.]

Gray was intensely devoted to the technical matters required to tell a realistic story set in space, but he was also engrossed in the mythical, philosophical and artistic concepts behind it. “Every camera angle, the mood and color of every shot — you have to come to a meeting of the minds,” Gray remarks. “Painting is where I start with the cinematographer — for color and for direction of light — then we’ll look at movies and other visual media. We even play music, because what we’re reaching for is nonverbal and unconscious.”

“The best way to begin any collaboration is to create a base of references, rather than try to find a formula,” says van Hoytema. “James wanted us to look at avant-garde films from the 1950s and ’60s. I started collecting a lot of still photos and color references — not just for color, but also composition. We also looked at a lot of space films to make sure we weren’t doing the same things.”

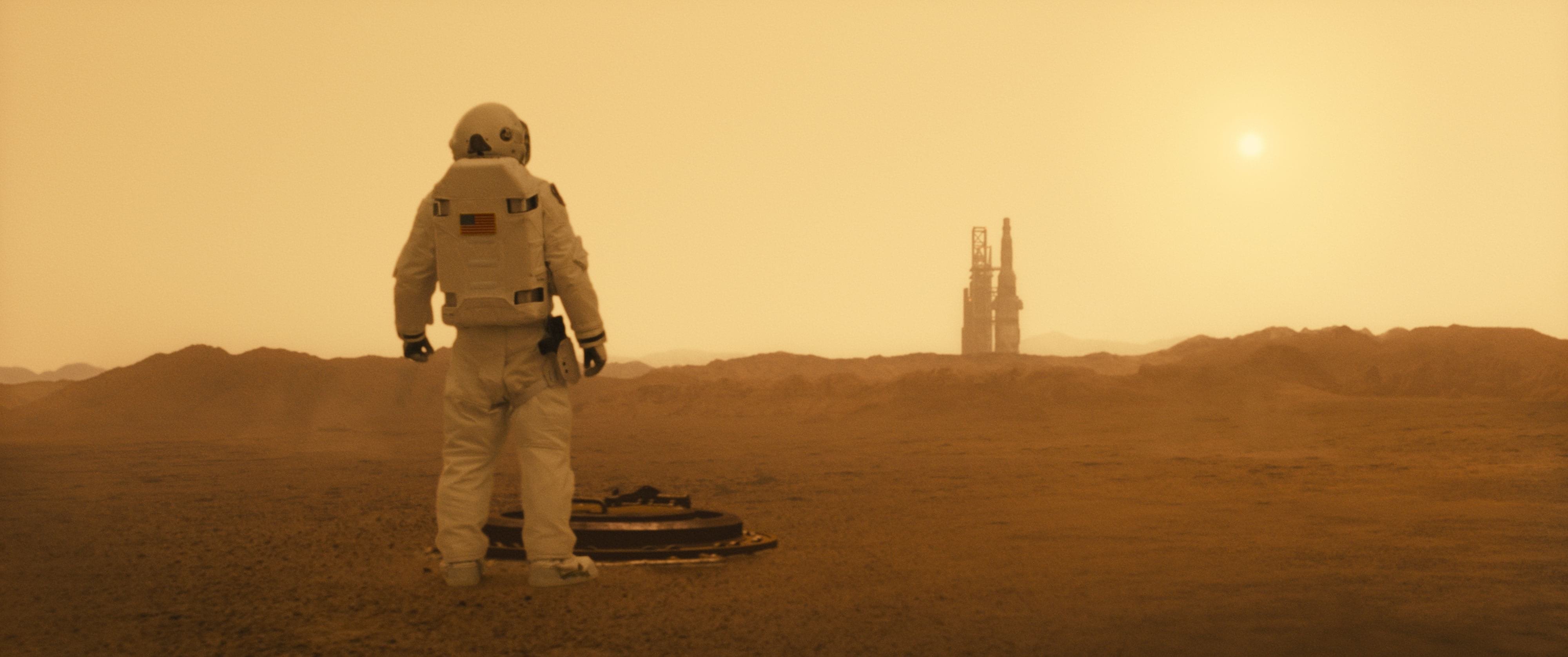

For Ad Astra, the filmmakers sought a visual language to convey distance, time and Roy’s state of mind as he makes the journey from the Earth to Neptune, and so the color and intensity of light from the sun became an important element in the film’s lighting design. The farther Roy travels from the sun, the more isolated — and isolating — the colors become, starting with pure white sunlight, to orange-red light on Mars, to the subdued blue-violet light over Neptune.

Van Hoytema wanted the audience to always be conscious of the sun’s position, and how far away Roy is from it. He noticed in his research — specifically in the 1998 HBO docu-drama series From the Earth to the Moon (photographed by Gale Tattersall; AC April ’98) — how the straight wavelengths of sunlight coming through the thick glass windows of the Apollo spacecraft looked like a spotlight. “Sunlight has an extremely straight beam because the source is so far away,” van Hoytema reasons. “When it hits you, the shadows have a very hard edge, so we wanted our single light source as powerful and far away as possible.”

The production’s biggest artificial sun source was an Arrimax 18K HMI positioned on a condor. Smaller units were used for close-ups: 400- and 800-watt Jo-Leko HMIs, and a 1,200-watt Dedolight DPB70 parallel-beam light, which van Hoytema describes as “almost like a big PAR, but instead of throwing the light in a wide angle, it uses a system of mirrors to converge everything into a straight beam with a hard shadow.”

In studying From the Earth to the Moon, van Hoytema also noted how sunlight would refract through the Apollo spacecraft’s window glass. “We tried to replicate that with every kind of glass you could imagine, with every kind of light,” gaffer Adam Chambers recalls. “Mario Ramirez at Industrial Glass Products, a female-owned business in Los Angeles, made us two pieces — equilateral triangles, 6 inches on all sides — of the purest glass you can find.”

The prisms were handed off to special-effects supervisor Scott Fisher, who cut them into thirds and designed a spinning bracket apparatus for the sliding mechanism of a Jo-Leko lens. When hitting the prism at a certain angle, the light splits into its discrete visible-spectrum colors.

Next, van Hoytema turned to ASC associate member Kavon Elhami at Camtec in Los Angeles for a set of lenses to capture the full breadth of the sunlight effect. By removing the lenses’ modern, efficient anti-reflection coatings through a fine-increment process called lapping, a full set of spherical Arri/Zeiss Master Primeswas modified for lower contrast and increased halation and flaring when the elements are hit with a direct light source.

Taking the process a step further, the curvature of the lenses’ front elements was ground to increase falloff around the edges of the frame while maintaining a consistent sharpness in the center. “Because they’re based on good lenses, texture-wise they all look the same if you keep the light out of them,” van Hoytema explains. “The difference is in how they respond to light.”

While this modification may increase the overall apparent brightness of the image due to an increased susceptibility to glare, Elhami notes a negligible reduction in transmission from the lenses’ stock T1.3. “The optics of high-quality lenses like Master Primes are designed to channel light straight through the glass with minimal [internal] reflections,” he says. “The modifications we did actually added reflectivity.”

The resulting lenses are what Camtec now refers to as “Astra Primes,” which van Hoytema used for most of the film, along with a full set of standard Master Primes. (The modification process isn’t without its risks: At one point, a glass element from the 25mm prime flew off the lapping machine, hit the ground, and cracked. Van Hoytema had Elhami remount the broken glass into what became the “Disastra” lens.)

Principal photography commenced in August 2017 and lasted three months. The decision was made to shoot on Kodak Vision3 250D 5207 and 500T 5219, in the 2-perf spherical format, using Arricam ST and LT bodies as well as van Hoytema’s personal Aaton Penelope for handheld work.

Practical locations were used for the scenes set on Earth, the moon and Mars, and included the erstwhile Sunkist headquarters in Sherman Oaks, the Los Angeles Hall of Records, and L.A.’s iconic Union Station. Below a disused department store in downtown L.A. lies an abandoned Red Car subway terminal, which was used for the underground tunnels of Mars. A former Los Angeles Times printing facility in Orange County was converted into the launchpad for McBride’s trip to the moon. Spacecraft interiors and exteriors — the lunar module, the Cepheus, the derelict Vesta, the ailing Lima — and spacewalk sets were housed on Stages 1 and 2 at Los Angeles Center Studios.

The scene in which SpaceCom orders Roy to Neptune was filmed in the boardroom of the former Sunkist headquarters, a low-rising, late-Modern Brutalist structure designed by A.C. Martin and Associates. Roy’s commission is effectively a death sentence, the severity of which is counterbalanced by a decidedly soft light that dominates the room from above. “The fluorescent softbox in the boardroom table actually hadn’t worked in 15 years,” Chambers reveals. “Our fixtures team repaired it and installed 3,200K tubes.” An overhead 4'x8' LiteTile from LiteGear was used to augment the existing source, and an Arri SkyPanel S60 provided fill and eye light.

The first stop on Roy’s journey is the moon, where humanity has gained a strong foothold, complete with lunar base and mini-mall. The main lunar concourse and tunnels are a combination of polished and rough-faced concrete, with a neutral color palette of gray and brown tones. The light here is dingy and fluorescent, with a base temperature of 3,200K provided by SkyPanel S60 and custom LED fixtures — designed by van Hoytema and fashioned by fixture foreman George Lozano Jr. — with points of green and cyan added.

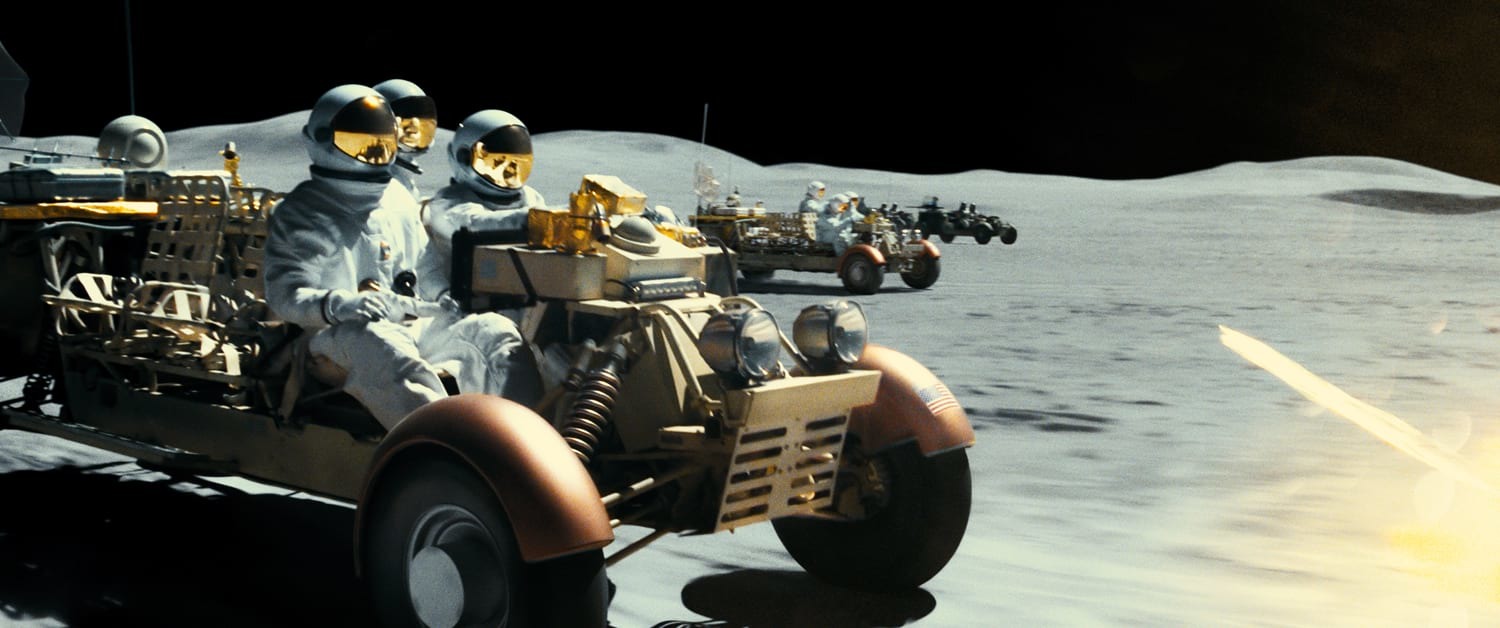

Outside, the hard, unfiltered, full-spectrum white sunlight on the lunar surface — casting razor-sharp shadows on the colorless, rocky landscape — was inspired by photos from the Apollo 13 mission and footage from various moon landings. It’s this landscape that Roy and his mission companion, Col. Pruitt (Donald Sutherland), must cross in a rover in order to reach a secret launchpad where they will board the Cepheus, the rocket that will take them to Mars. “Our challenge was to sustain that light quality throughout a big area,” van Hoytema notes. “It left us with no other option than to use real sunlight, as any single artificial light source spreading over such a big area would have huge falloff and [produce] softer shadows.”

En route to the launchpad, Roy, Pruitt and their escorts are ambushed by moon pirates (above) — free agents capitalizing on the final frontier’s unfettered market potential. The sequence’s live-action elements were photographed by van Hoytema onstage at L.A. Center Studios (for Pitt and Sutherland’s close-ups), and by 2nd-unit cinematographer Chris Moseley with a stunt crew at Dumont Dunes, in California’s Mojave Desert.

It wasn’t enough to simply photograph the stunt-actors and rovers in a lunar-like environment, then paint in the appropriate background with visual effects. To capture large distances with the proper contrast ratio and quality of light, van Hoytema started experimenting with combining a digital infrared image with an analog 35mm color image. A 4-perf Arriflex 435 loaded with Kodak 250D 5207 and an infrared-modified Arri Alexa XT were mounted to a modified 3Ality Technica Quasar 3D rig, which was perfectly aligned “so you end up with a single image captured by two completely different mediums,” the cinematographer explains. The customizing of the cameras and 3D rigs for the chaotic chase sequence was entrusted to Camtec. Using an Alexa XT B+W’s infrared mode as a reference point — the cameras themselves were unavailable for production — five Alexa XTs were modified with a filter that allows only infrared light to pass through, turning the daylight sky black and the sandy ground almost perfectly white. “To get a darker sky, we needed IR pass filters that went higher than 850nm,” A-cam 1st AC Keith Davis recalls. Schneider Optics’ Ron Engvaldsen was able to supply the production with 1,000nm IR pass filters in 138mm round and 4"x5.65" rectangular sizes from their stock of blanks.

Camtec also purchased two 3D rigs, disabled their convergence features, and improved their mirrors’ rigidity so that the film and digital cameras would remain in perfect alignment while bouncing up and down on the end of an Edge Crane. The rigs used matched standard Master Primes, but because infrared light comes to a focus differently than visible light, each focal length meant for the infrared cameras had to be individually calibrated, using the sun as the light source to match the filming conditions. After heavy testing by Davis, the rigs were put into use by 2nd-unit A-camera 1st AC Chris Toll and B-camera 1st AC Ray Milazzo, who aligned and synced the lenses to the 435s via Preston MDR2s and 3D software. The color and infrared images were first combined on-set in a proof-of-concept by 2nd-unit DIT Elhanan Matos, then later in post by visual-effects artists at Atomic Fiction, one of Ad Astra’s three main visual-effects vendors along with MPC and Weta. “The IR rig had stronger luminance and base values, so we used that for our base layer, then extracted our color information out of the analog film and laid a digital film grain over everything,” visual-effects supervisor Allen Maris explains. Despite the filmmakers’ best efforts to photograph the scene by practical means, “all we were able to extract from that footage was the rover, a little bit of the foreground, and a little bit of the middle-ground,” says Maris. “Everything else was digitally created.”

While the moon is depicted as a highly developed network of outposts, Mars feels more like a subterranean research station in Antarctica. “We knew that it was going to be underground, but we didn’t want it to be like anything anyone had seen before,” production designer Kevin Thompson relates. In addition to the abandoned Red Car station, the production filmed much of the Mars-based scenes in an unoccupied power plant.

“Mars was going to be very orange, not only because of the surface of the planet, but because Mars is the last colony of humanity, and it should feel like an incubator where humans are surviving by purely artificial means,” says van Hoytema, who took his inspiration from oil rigs and industrial factories. “We wanted it to feel as if resources are scarce, so we needed light that felt energy-deprived, like sodium vapor.”

“Hoyte actually had our team build high-pressure 1,000-watt sodium-vapor McMaster-Carr lamps into the tunnel set to make it super-orange,” Chambers says of the sequence in which Roy hurries to board the Cepheus for the final leg of its journey to Neptune. “We matched the sodium color with SkyPanels for the tighter shots and close-ups.”

All of Thompson’s designs for the spacecraft in Ad Astra are rooted in real-world space-faring technologies: Skylab, the International Space Station, the space shuttle and space rockets. “James was against a cruise-ship fantasy vision of the future,” Thompson elaborates. “We included things from different time periods to convey the idea of new technology colliding with things from the past.” Two versions of each zero-gravity set were constructed, one horizontal and one vertical, allowing the filmmakers to suspend the actors in different orientations relative to the sets and from wires as high as 30' in the air in order to simulate the effects of weightlessness. With 90 percent of each ship’s lighting consisting of custom-built tubes — “Hoyte’s special LED tubes were the workhorse of the show,” Chambers notes — that were then supplemented with SkyPanels, van Hoytema was able to control his colors and levels almost entirely over wireless DMX, as well as power whole sets off of key grip Herb Ault’s CineJuice block batteries. Van Hoytema also used this opportunity to experiment with custom LED lamps, called Nucleosomes, from his own company Honeycomb Modular. “One thing that came out of Ad Astra was the need for small, hard and clean light sources,” the cinematographer relates. “We designed and built the Nucleosome with similar specs to an Arri M18, but it’s smaller, fully dimmable, and DMX controllable, with low energy consumption.”

Lamps and fixtures were routed through RatPac wireless dimmers to board operator Sean Hogan, who worked off an iPad or a High End Systems Wholehog III on a mobile cart next to van Hoytema during each setup. According to Chambers, the cinematographer tends to work on the fly, lighting either by eye or by reference stills taken with a Leica digital camera. Luminance and color meters were rarely used.

When it came time for Roy or any of the other astronauts to leave the safety of their spacecraft, they were photographed against large black screens on stages at L.A. Center Studios. “If you want a wide shot of tiny astronauts floating in the vastness of space, you can usually just reframe them in post,” van Hoytema observes. “We tried to stay true to the frames we actually wanted, and ended up with a lot of negative space in many of our shots. Having the actual black space to work in helped us find our composition a lot easier.”

With the characters already floating against a void, visual-effects artists needed only to add spacecraft, star fields and other celestial bodies to the background. “In the wide shots, the whole of space is visible, but in close-ups, you only see the actor’s face and a few stars,” says Maris.

Such is the scope of Ad Astra — for every cosmic vista, there’s a close-up of Roy taking it all in. “The moment you go into space, distance becomes an abstract thing,” says van Hoytema, who also operated the A camera, with Kristen Correll on B camera. “How can an audience understand the distance between the moon and Neptune? On such a journey, everything you’ve ever known is slowly slipping away, and every day that distance becomes more abstract, until your detachment becomes so powerful that you turn completely inward.”

Gray adds, “What I was trying to say with the close-ups in this film was that, as an unknown, deep space isn’t anything we can relate to. What actually matters is the human being; the true terra incognita is the landscape of the soul.”

Film processing for Ad Astra was handled by FotoKem, with scanning at 6K performed at EFilm in Hollywood. Dailies were graded in 2K at EFilm by EC3 colorist Matt Wallach. The final grade was performed at 2K by Company 3’s Greg Fisher, who worked in Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve, first at Company 3 London, then at EFilm Hollywood.

With the final grade, the filmmakers sought to bring out more nuance and variation in the palette as needed. Prior to shooting, Fisher had developed a LUT that was then used both on set and as a starting point for the dailies grade. This LUT emulated the characteristics of a film print, but allowed for extended shadow and highlight detail beyond what could be practically displayed through a purely photochemical process.

“We didn’t need things to be too polished,” Fisher notes. “Hoyte wanted the 2-perf grain structure to be apparent. The visual-effects work was completed without the final grade, so there were times when those shots required some fine-tuning in Resolve. To ensure that all of the visual-effects elements sat well alongside the live-action elements from each shot, it might involve selecting the CGI portions and then doing some de-graining or re-graining, or just adding some careful contrast adjustments.”

While van Hoytema’s regard for subtlety and precision was mission-critical to the success of Ad Astra, it’s his willingness to cross boundaries and venture into uncharted territory that garners the highest commendation from Gray. “Hoyte understands how imperfection allows art to form,” the director says. “I love his boldness with color, his willingness to let parts of the frame go completely dark or overexposed. And it’s all so deceptively simple. These are the things that make a film memorable, that allow you to recall it days, months and — dare I say it? — years later. It’s what you hope for, and that’s what Hoyte gave to me.”

Collaborator Spotlight: 1st AC Keith Davis

American Cinematographer: You’ve been working as a camera assistant for more than 25 years. How did you get your start?

Keith Davis: Working with cameras is something that I’ve always been passionate about. As a child I always wanted to be a photographer — but, I realized as I got older, not for my 9-to-5 gig — and thought that being exposed to the movie industry offered a camera-related opportunity to make a good living, travel the world, and fund my photo hobby on the side.

I started as a PA in the locations department on non-union productions, doing all kinds of jobs: grip, electric, camera assistant, loader. Eventually, 1st assistant Ron Schlaeger and cinematographer Michael Fash hired me to be their loader on a TV series titled Christy. After working for Fash and Schlaeger for a few years, Ron brought me onto Nash Bridges as a 2nd, and after three seasons I ended up moving to full-time B-cam 1st.

When did you begin your collaboration with Hoyte?

Davis: We started working together on Her [AC Jan. ’14], and since then we’ve developed a good working relationship doing commercials and features. We’re friends, but at work he’s my boss. I think it is very important to keep that in perspective.

How would you characterize your professional relationship with Hoyte?

Davis: The 1st AC works very closely with the operator, and because Hoyte also operates, that makes the bond between DP and 1st assistant even closer. He empowers me to make my own decisions, and he gives me a lot of freedom to run the camera department, including hiring all the personnel. Having the right personalities on set is important because you’re part of a team, and we all have to work towards the same goal.

How would you characterize the role of the 1st assistant?

Davis: The job of a good 1st is to run the department while being invisible. It’s not about me. We provide an environment for the actors to do what they do. We also provide the DP and the director with the tools to do their jobs. They don’t wait on us; we facilitate with efficiency.

What are some of the most important qualities a 1st assistant should possess?

Davis: Good technical skills and knowledge along with good management skills. Being able to listen and pay attention. Adaptability and anticipation. Understanding story.

Can you elaborate on that last item?

Davis: A 1st assistant has to be able to understand and tell a story, because the focus is steering the audience where to look. Sometimes all you have to do is keep the subject in focus, but for certain movies — like Ad Astra — a well-timed focus pull tells a different story than a fast one. It’s in the psychology of how your eye works. During prep I’ll read the script and try to get into the director’s and the cinematographer’s heads to understand the feeling and language of their film.

Having worked with a lot of different cinematographers, what would you say is unique about your collaboration with Hoyte?

Davis: Hoyte tries to bring something different to each project he does. He’s not an off-the-shelf cinematographer. He’s very much interested in inventing things, and if he can’t machine it himself he’ll find the right people to help, like with the Astra Primes and the 3D rig for the chase sequence on the moon, both of which he developed with [ASC associate] Kavon Elhami at Camtec.

What do you love about the job?

Davis: I enjoy the problem solving and the pressure of working on feature films — it’s like playing in the Super Bowl every day. It’s not glamorous to say I’m an assistant. It’s a thankless job sometimes, but it’s an important one. The Baird Steptoes, the Bob Halls, the Tony Rivettis and a whole host of career 1sts in this business — they’re not DPs or operators, but the quality and body of their work is amazing, and someone has to keep it all in focus. — Iain Marcks