Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope — Something Different

The Master of Suspense experiments with camera movement and "real time" in this classic mystery.

Many movies have been criticized as being “the same old stuff.” Such a complaint could never be leveled at Rope, which was produced by Alfred Hitchcock 37 [now 74] years ago. Rope was one of a kind.

In 1946, Hitchcock and his old friend, Sidney L. Bernstein, a theater magnate, formed a producing company called Transatlantic Pictures Corp. While dining at Bernstein’s London home, Hitchcock was intrigued by an idea proposed by Bernstein that stage plays should be photographed during performances for research purposes.

Hitchcock mentioned a 1929 play by Patrick Hamilton, Rope’s End, which he believed would be ideal for such a treatment. He proposed to shoot the play, which has no time lapses and takes place in one set in an hour-and-a-half, as continuous action. “The camera never stops,” he explained. But the picture should not be made on a theater stage but under sound stage conditions. The partners decided to buy the play and film it as the first Transatlantic production. Hitchcock soon debarked to America to direct the last picture required by his contract with David O. Selznick, The Faradine Case.

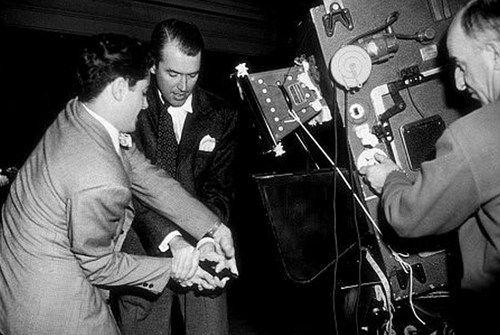

Star names were necessary to carry a picture in those days. Transatlantic decided to get one box office star, James Stewart, and assign the other roles to dependable - but less expensive - players with stage experience. Stewart’s fee — $300,000 — was a large disbursement for an independent company. The other players: John Dall, Farley Granger, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Constance Collier, Joan Chandler, Douglas Dick, Edith Evanson and Dick Hogan. Rope was the first of four pictures Stewart made for Hitchcock.

Technicolor was another sure-fire selling point. Hitchcock decided that Rope would be his first color picture.

The concept of shooting a picture in “real-time” was not, in itself, unique. For several years following the introduction of motion pictures in 1894, short films dealing with simple situations were filmed with locked-down cameras from a single vantage point. As productions grew longer, individual shots became shorter — but only gradually. After 1910, the value of editing a picture from many shots of varying lengths and angles became standard procedure, and by 1920 the average feature contained about 600 shots. The art of shooting and cutting film into a unified whole had reached a high state when, in the late 1920s, the talking picture made silent production methods obsolete.

Extremely long takes became a necessity because of the many unresolved problems of combining photography with sound. There was a general reluctance to attempt cutting during a scene, and a long scene was made more dreary by the fact that the camera was confined to a soundproof booth and the actors had to huddle around a hidden, low-fidelity microphone. The invention of the mike boom freed the sound apparatus and the soundproofing of cameras with blimps freed the cinematographer from camera booths. Cutting within a dialogue scene was achieved successfully in 1929 by Tod Browning and Merritt Gerstad, ASC — director and cinematographer of MGM’s The Thirteenth Chair — during the filming of a seance scene.

While directing The Bat Whispers at United Artists Studio, Roland West bought a 65mm camera at his own expense and made a second version of the picture in the wide format. His idea was to make the picture in actual time in the manner of a stage play, to be projected on a huge screen on which the players would appear life-size, as though acting in person on the stage and enacting their roles without interruption. The camera was mounted in a single position, remaining static except during the opening scene. The result was a stodgy picture far inferior to West’s standard 35mm version, which has wonderfully lively camera work, special photographic effects and sharp editing.

Although many directors — Victor Halperin, Ernest Schoedsack, Frank Capra, George Cukor, Preston Sturges and Vincente Minnelli among them — made occasional very long takes, they kept them isolated among more normal cuts.

Hitchcock’s plan was to shoot all nine reels of Rope with the usual variety of camera angles from closeups to long shots without cutting. The camera would be kept in continuous motion, prying into the action as an invisible visitor — a major departure from West’s pioneering effort.

In 1947, while completing The Paradine Case, Hitchcock and Bernstein signed Arthur Laurents, a successful Broadway playwright, to adapt Rope’s End. The picture was to be produced at Warner Bros, for their program. The script is a unique document in that the scenes are not numbered or separated and there are very few camera directions other than some notations of positions required at certain crucial points

Hitchcock had never worked in Technicolor before, having purposely avoided color photography because he felt that his type of story generally worked better in black and white. He decided to do Rope in color because, he said, “Color will denote the change in time of day from sunset to darkness which is of vital dramatic importance in the story.”

Technicolor, at that time, was a process that utilized three strips of black-and-white film passing through a specially constructed Mitchell camera to produce the panchromatic equivalent of three basic colors, which were printed onto a single strip of film by a dye-transfer method. It was a ponderous, expensive system fraught with difficulties, but was capable of producing results surpassing those of any other available process. Three-strip Technicolor is quite extinct now, except in the Chinese film industry.

Dick Hogan, has already been tucked out of sight.

Because only 952 feet of Technicolor could be shot at one time, filming was done in segments of nine minutes or less. To hide the changes between reels it was necessary to resort to various forms of trickery. In one instance, the lid of the sinister chest is raised, momentarily blotting out the scene as it comes close to the camera lens. Sometimes the camera freezes on some part of the room not occupied by actors, picks up the same view on the next reel and continues the camera movement. Most often one of the players brushes past the camera or the camera moves in close to somebody’s jacket at the end of the take.

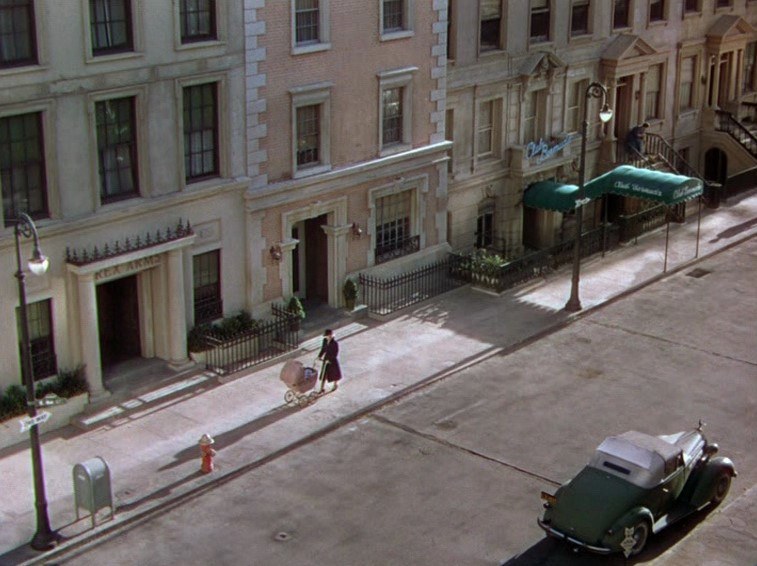

The opening reel actually encompasses two shots. The first is a high angle looking down at a city street; then the camera swings around to show a high window with drawn blinds. A scream is heard from inside. Then the camera is in the apartment and the long take begins with an extreme close-up of Dick Hogan’s agonized face. The camera pulls back to show that he is being strangled by a rope held by John Dall and Farley Granger. The boys stuff the body into a large wooden chest. The camera follows them through the hallway and dining room to the kitchen, watches them open a bottle of champagne, and returns with them to the chest where they discuss their crime and their plans for the evening as they set the silver service on the wooden tomb in preparation for a buffet dinner to which the corpse’s family and fiancee have been invited.

During the ensuing eight reels, we learn that the two young men have murdered their college friend merely to prove their superiority. Amongst the guests is their former professor, James Stewart, whose teachings of the Nietzsche superman theory have inspired the crime. In their attempts to impress Stewart, the murderers arouse his suspicions. After the party, he returns to confront them with their guilt and turn them over to the police.

The camera moves were not improvised to any noticeable degree. Hitchcock’s method always was to pre-plan a production so intricately that the actual filming was relatively simple. A series of conferences with key production personnel to iron out technical problems began in December 1947, about one month in advance of principal photography. Among those present at these meetings were Joseph A. Valentine, ASC, director of photography; William V. Skall, ASC, a cinematographer furnished by the Technicolor Company; William Ziegler, film editor; Perry Ferguson, art director; Lowell Farrell, assistant director; Fred Ahern, production manager, and Emile Kuri and Howard Bristol, set directors.

Ziegler planned out the movements of actors and camera by rearranging the rooms of his daughter’s doll house and using chessmen as actors. The art director and the cinematographers used Ziegler’s choreography to plan their moves, which were extremely intricate.

All action except for a brief opening scene was shot on a single set. The designer, Perry Ferguson, was one of the top men in his field, having done the sets for the likes of Gunga Din (1939), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1940) and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947). His ingenious set for Rope depicted a penthouse apartment consisting of living room, dining room, hallway and part of a kitchen. All the walls were wild, being hung from overhead U-tracks so that grips could move them out of the camera’s way as it followed the actors through doors, then replace them before they came back into camera range. The rails’ grooves were filled in with petroleum jelly so that there would be no friction as the walls were slid back and forth.

All the furniture, including a massive wooden chest that plays an important role in the story, was on wheels so it could be moved out of the camera’s way. The chest, which appears to be in the middle of the living room throughout, actually was rolled away every time the camera moved across the room, then returned to its position before the camera returned.

To keep such behind-the-camera action noiseless, the set was built on a special floor on Warner Stage 12. Built of 1" tongue-and-groove lumber covered with soundproof Celotex and a carpet, and lined with felt, the extra floor assured that there would be no creaking as the heavy Technicolor camera and dolly passed over. The floor was marked with numbered circles showing where the camera should be situated at a given time. The positions were also plotted on a blackboard. A continuity supervisor signaled the crew for each move indicated on the board. A small flashlight, suspended just under the camera lens so that its circle of light marked the exact position of each number, helped the grips to place the camera in position for each cue.

Valentine, a stocky New Yorker of Italian descent, had photographed most of the Deanna Durbin pictures, The Wolf Man (1941), and two of Hitchcock’s earlier pictures, Saboteur (1942) and Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Skall was a specialist in Technicolor photography, whose credits included Ramona (1936), Northwest Passage (1940) and Billy the Kid (1941). It was his job to advise Valentine, whose specialty was black-and-white work, on the considerable differences in technique demanded by the color process.

Rehearsals began on the full-size set on January 12 and continued daily until January 22, when actual photography commenced.

The camera was mounted on a special dolly invented by Morris Rosen, head grip, and called “Rosie’s all-angle dolly.” It was made for $1,700 and consisted of a square platform, a camera post, and wheels. It operated without tracks and was small enough to pass through a normal double door. The camera post would rise four feet noiselessly. Each set of double wheels was separately pivoted. A chain attached to the steering handle turned all wheels simultaneously, allowing the camera to circle a player in closeup. “Rosie’s dolly” was the prototype of the crab dolly which is used widely today.

Finding that it was impractical in most instances to follow the camera with a mike boom, the sound supervisor, Al Riggs, used four separate booms and two overhead mikes to pick up dialogue from anywhere on the set. Five mixers and as many boom operators were busy keeping up with the camera moves, while the mixer operated his console from a high parallel overlooking the set.

A 35mm lens, which offered a somewhat wider angle and deeper field than the normal 50mm, was used throughout, taking in 1 ½ foot closeups to 30-foot long shots. A Selsyn motor, calibrated to the lens, was employed to insure correct focus.

“My biggest problem was the lighting,” Valentine told American Cinematographer (July, 1948). “Especially the job of eliminating mike and camera shadows. In the reel where we had ten mikes in operation, we had to have electricians operating five dimmer panels.” All lighting had to be set up overhead, television style.

Valentine and Skall kept the colors subdued throughout, except for a few moments at the end of the picture. The lighting and colors within the apartment itself are purposely undramatic and ordinary looking, with none of the sinister film noir look of most murder yarns. The dramatic color effects were limited to the scene outside the window, in which the passage of time had to be dramatized convincingly.

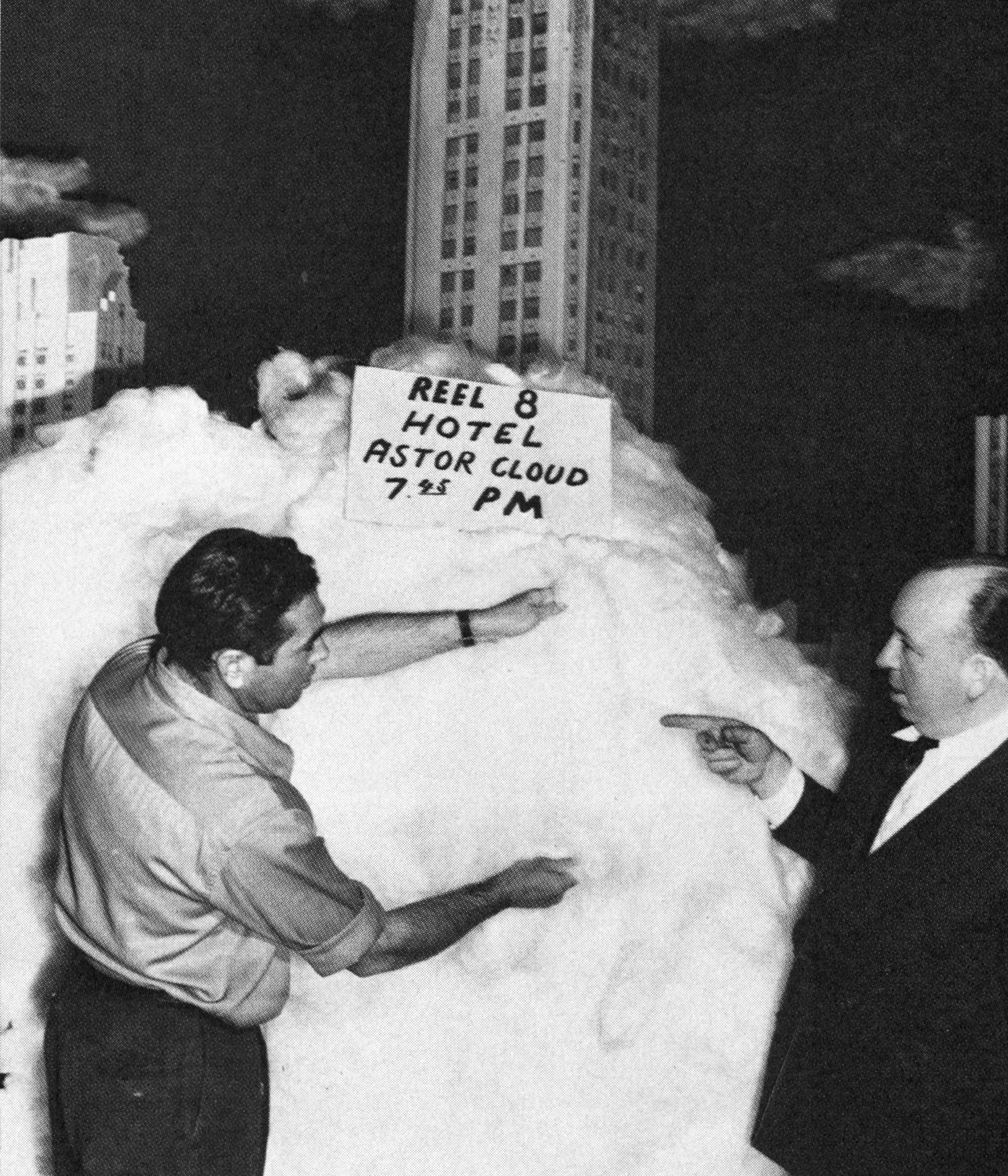

No Hitchcock picture would be complete without some use of miniatures. In Rope, in which there is none of the usual hectic action featured in the typical thriller, the miniature is a part of the set — the view of New York City which appears beyond the windows in every reel.

It was apparent from the outset that the customary painted backdrop, however artfully lighted, would be inadequate to show the changing light and cloud formations needed to depict the passage of time from late afternoon to night. The importance of this effect to a story being told in “real-time” was crucial.

The miniature reproduced about 35 square miles of the Manhattan skyline, taking in such familiar landmarks as the Empire State Building, St. Patrick’s Church, the Hotel Astor, Radio City, and the Chrysler and Woolworth buildings. The 12,000-square-foot cyclorama backing was three times as wide as the apartment and was laid out in a semi-circle so the camera could be moved around freely without compromising the background. The buildings, built-in forced perspective, were similarly arranged. The closer structures were three-dimensional and equipped with steam pipes inside to feed “smoke” through chimneys and stacks. It was noted initially that the steam rose too rapidly and too high for the scale of the set. Dry ice, placed over the pipes, solved the problem. The chilled steam rose lazily and drifted away.

The more distant buildings were photographic blowups shot in New York, printed up to scale and mounted as double-faceted cutouts. The farthest buildings were only 20 feet from the window, but with extreme fore-shortening and effect lighting, they give a proper impression of distance.

Fred Ahern, production manager, got the job of finding clouds that looked real and could be changed subtly between takes. Clouds of cotton wool were tested and rejected because they absorbed the light instead of reflecting it. Eventually, the clouds were made of spun glass (“angel hair”). Scenic artists wearing cheesecloth-lined painting masks modeled 500 pounds of the fragile substance over chicken wire forms to produce a variety of cumulus cloud shapes, which were arrived at after hundreds of photographs were studied. The clouds were mounted individually on stands or suspended from tracks on invisible wires.

Dr. Dinsmore Alter, head of the Griffith Observatory in Hollywood, was brought in to examine the clouds for authenticity. The noted meteorologist-astronomer made certain that the shapes were correct for their levels and had one group broken up because it resembled an atomic mushroom.

In the course of filming, the clouds were rearranged between reels, moving left to right according to a carefully drawn-out plan. In the opening scenes the sky is crowded with clouds, which thin out as nightfall approaches until at the end there are only two clouds in the blackened sky.

As the sky darkens, lights begin appearing in the windows of the buildings and neon signs flash on. One of these signs depicts before-and-after figures advertising a product called Reduco. The model for this was the director, whose portly figure is well known, making the token personal appearance that had been a tradition in his films since The Lodger, made in 1926. He had used the Reduco gag as a newspaper ad in Lifeboat (1943), another one-set show in which he could not logically do a walk-on.

An electrician stationed on a high parallel operated a light organ with a bank of 47 switches to control the miniature lights. Some 6,000 incandescent bulbs ranging from 25 to 100 watts lit the windows and 200 tiny neon signs adorned the exteriors of the buildings, all of which were wired separately. This required 26,000 feet of wire carrying 126,000 watts of power to 150 transformers.

A full-scale neon sign spelling out STORAGE in three colors — red, blue, and green — was installed near the window. This sign begins flashing just at the climax of the movie, when the murderers are revealed, so to speak, in their true colors. The neon provides lurid punctuation to a film of predominantly subdued hues.

To make the light from the sign seem to flood the room and limn the faces of the killers, lights covered by gels of the same colors as the neon were set up. Shutter devices, electrically synchronized to the blinking of the sign, created the dramatic pulsing of the colors.

“Our worst calamity,” Valentine said, “was the day one of the wild walls didn’t move quite fast enough and the camera went crashing right into it. The crackup jimmied the friction head of the camera and we suspended filming for the day.”

The Rope technique, Valentine said, created more problems for the crew and required more careful planning than the conventional methods, but he felt it was beneficial to the actors. “The way we usually film a scene, by making first a master shot, then a medium shot, then finally a close-up, keeps the actors waiting endlessly. By the time we get around to the close-up, the stars are exhausted and the spontaneity of the scene is lost; but with this reel-by-reel filming the actor can sustain a characterization and maintain an even flow and pace in his work.”

A typical technical problem occurred while the first reel was being shot. After about eight minutes of a perfect take, the last camera move caught an electrician standing by the window.

Rope was completed, supposedly, in only 18 actual days of production — 10 days of rehearsals with actors, camera and crew, and eight days of shooting. Hitchcock, however, was displeased with the first version of the sunset, which was treated in a conventional movie style with an abundance of red-orange light. He decided to retake the last five reels of the picture. He sent photographers to three locations to photograph the setting sun at five-minute intervals for 105 minutes. One made his shots from the top of a New York office building, another from an unfinished building on Wilshire Blvd. in Los Angeles, and the other from Santa Monica pier.

The five reels were re-shot, using the photos as color guides. At this time, Valentine was on the sick list and Skall took charge. Nine days later the last reel was completed.

Incidentally, Hitchcock was not entirely convinced that his one-take approach was viable, although he had experimented with the idea in individual sequences of Spellbound (1945) Notorious (1946) and The Paradine Case (1947). He spent several days shooting closeups of key dialogue scenes, “just in case...”

The street sounds, including the approaching police siren at the climax, were real. Nixing the sound department’s intention of utilizing library sound effects, Hitchcock had microphones hung outside a sixth-story window while actors, autos and an ambulance performed to order. The effect is perfectly realistic.

The original cost estimate of Rope was $1.4 million, including studio overhead charges. Neither time nor money were budgeted strictly because it was impossible to anticipate what problems might arise. The 28-day completion was well under the schedule usually given important pictures, and the cost of $200,000 above the estimate was hardly excessive. There was a minimum of postproduction work.

The picture was released nationally on September 25.

The movie industry’s own self-censorship board, established by the studios to keep producers from running afoul of local and state censors, rode herd on the script and production, making certain there was no direct allusion to the homosexuality of the murderers (and the bestiality of one of them), and that the murder scene was not unduly gruesome. The picture received the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America “purity seal,” meaning it was, ostensibly, “censor-proof.” However:

The Chicago censors banned Rope in toto. Authorities in Worcester, New Bedford, Spokane, Seattle and Memphis followed suit. Chicago later relented, with the condition that exhibitors enforce an “adults only” policy. Sioux City permitted exhibition only after the murder scene was deleted. Women’s organizations, the National Legion of Decency and other influential groups denounced it.

Fortunately for Transatlantic, Rope received generally high marks in the press, few reviewers remarking dislike of either the theme or the technique. A number even went overboard and proclaimed it “as important as the invention of the closeup or of sound.” Life, selecting it as Movie of the Week, gave the sensible opinion that the “radical innovation in picture-making” was effective in maintaining suspense but that Hitchcock’s effort at making his technique unobtrusive was “not a wholly successful one.” On the other hand, the esteemed Thornton Delahanty, in Redbook, selected Rope as Movie of the Month, gave it a rave review, commented upon the “extremely effective” use of color “to dramatize the mood” and made no mention whatever of the photographic technique!

The public, undaunted by questions of technique, liked the picture well enough to make it a financial success. It put Transatlantic in a healthy financial condition and the company’s future seemed secure.

Hitchcock tried a modified version of the Rope technique on their next production, Under Capricorn, interspersing several long and complex takes into more conventionally arranged scenes, but they interrupted the tempo of the otherwise exquisite film and destroyed suspense. The usually imperturbable Ingrid Bergman became so angry while wading through one nine-minute scene that she was still raving on the set after the director had gone home.

Under Capricorn, which cost a great deal more than Rope and brought in a great deal less, was a fiscal disaster that forced Hitchcock and Bernstein to dissolve Transatlantic.

“I undertook Rope as a stunt; that’s the only way I can describe it,” Hitchcock said 20 years later in the book, Hitchcock by Francois Truffaut (Simon & Schuster, 1967). “I really don’t know how I came to indulge in it... When I look back, I realize that it was quite nonsensical because I was breaking with my own theories on the importance of cutting and montage for the visual narration of a story.” He also referred to it as “a crazy idea.”

It is, nevertheless, a fascinating show and is actually the only feature of its kind in the history of films. Its uniqueness alone gives it a certain monolithic stature and it is doubtful that it could have been done as well by other hands. In Rope, Hitchcock blazed a trail that nobody yet has followed.

You’ll find our complete 1948 article on the film here.

If you like coverage on classic films, there's much more here.

ROPE

A Transatlantic Pictures production; color by Technicolor; produced by Sidney Bernstein and Alfred Hitchcock; directed by Alfred Hitchcock; adapted by Hume Cronyn from the play, “Rope’s End,” by Patrick Hamilton; screenplay by Arthur Laurents; directors of photography, Joseph A. Valentine, ASC and William V. Skall, ASC; Technicolor color director, Natalie Kalmus; associate, Robert Brower; art director, Perry Ferguson; set decorators, Emile Kuri and Howard Bristol; film editor, William H. Ziegler; sound by Al Riggs; makeup artist, Perc Westmore; musical director, Leo F. Forbstein; music adapted from “Mouvement Perpetual No. 1” by Francois Poulenc; Miss Chandler’s dress by Adrian; radio sequence by The Three Suns; operators of camera movement, Edward Fitzgerald, Paul G. Hill, Richard Emmons, Morris Rosen; lighting technician, Jim Potevin; assistant director, Lowell J. Farrell; production manager, Fred Ahern; technical advisor, Dr. Dinsmore Alter; mechanical effects, Ralph Webb; continuity, Charlsie Bryant. Running time, 80 minutes. Premiere on Aug. 26, 1948 (New York City). Released in U.S. on Sept. 25, 1948 by Warner Bros. Pictures. (Reissued in 1983 by Universal Classics.)

Cast: Rupert Cadell, James Stewart; Brandon, John Dali; Philip, Farley Granger; Mr. Kentley, Sir Cedric Hardwicke; Mrs. Atwater, Constance Collier; Kenneth, Douglas Dick; Mrs. Wilson, Edith Evanson; David Kentley, Dick Hogan; Janet, Joan Chandler.