Rope Sets A Precedent

Each take averaged 925 feet in length in this newest of Alfred Hitchcock productions photographed on a single set.

By Virginia Yates

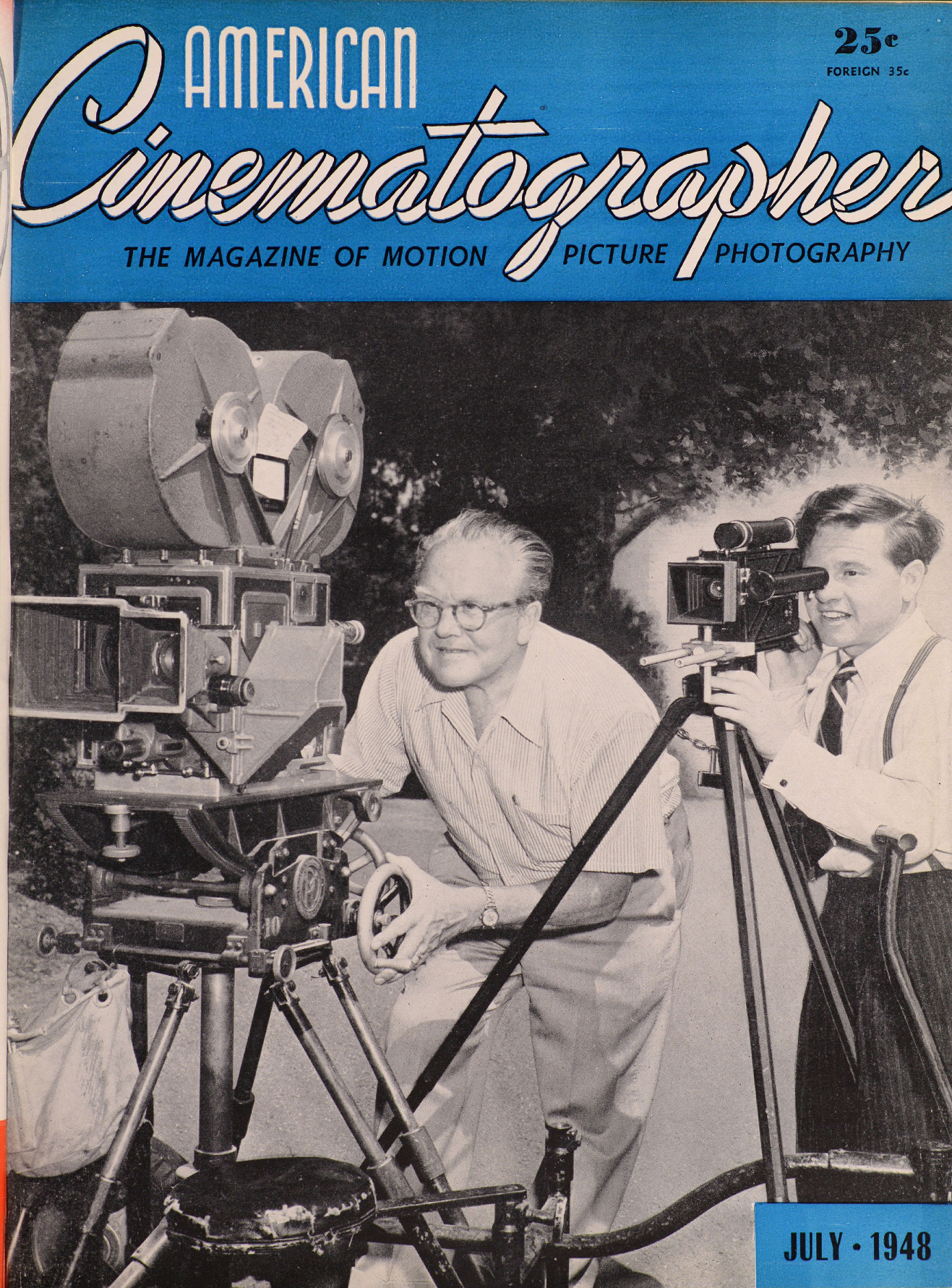

Not until September will you have an opportunity to see Rope. a picture demonstrating a unique and successful departure from the familiar technique of filming motion pictures. This Technicolor production, photographed by Joe Valentine, ASC, is the culmination of years of careful planning by director Alfred Hitchcock.

Actually, the planning of the picture began back in 1946. The locale was London. And the subject under discussion by Hitchcock and British theatre owner, Sidney L. Bernstein was 'how to make movies.’

"Why not film plays while they are enacted on the stage,” said Mr. Bernstein, "if not for commercial use, at least for research. Think what it would mean if we could sit in a projection room today and see Booth, Salvini and Sarah Bernhardt portraying their most famous stage roles.”

There is one play that would lend itself to such treatment,” said Hitchcock. "It’s Patrick Hamilton's play Rope’s End."

"You mean shoot a performance of it right on the stage?” asked Bernstein.

No. Shoot the play as it is enacted on a sound stage. Shoot the action continuously, stopping only when the film is used up in each reel.

Excitedly, Hitchcock outlined the idea and convinced Bernstein that this play was the perfect vehicle for the experiment. The perfect initial production for their newly formed company Transatlantic Pictures. Actually, the idea had been one of Hitchcock’s pet dreams for a long time. But he had needed a story that had no time lapses, and a story that took place on one set. Rope’s End, which will be released by Warner Bros, in September under the title Rope, was the perfect choice.

It was also Hitchcock’s idea to shoot the picture in Technicolor. "Because,” as he explained, "I’ve waited 17 years to find a story of my type in which color plays a dramatic role. In Rope, color will denote the change in time of day from sunset to darkness which is of vital dramatic importance in the story.”

Thus began a project that may prove to be as revolutionary in the technique of filming motion pictures as the introduction of the close-up, the camera boom and sound.

“The camera, rolling without a single stop through the entire film, is merely an aid to the story which is full of suspense.”

— Alfred Hitchcock

On Warner’s sound stage No. 12 a special floor was first built. It was raised four inches above the permanent floor and lined with felt. It was built absolutely level and rigid enough to carry the ponderous 685-pound Technicolor camera and boom without creaking or sagging. On this floor was constructed the one set for the film. It was a penthouse apartment consisting of a kitchen, dining room, hall, and living room. All of the walls were hung from overhead tracks so they could be moved manually to allow the camera to follow the actors through narrow doors, then be replaced quickly when necessary. It featured a large window and looked out over the New York skyline.

The miniature skyline was probably the most important background ever built for a motion picture because the lighting of buildings, the changing sky and cloud effects from sunset to dark — all seen from the apartment — were to denote the passing of time, so important in the story’s denouement. This exact reproduction of nearly 36 square miles of New York skyline was lighted by 6,000 25-watt incandescent bulbs for the windows in the buildings and 200 neon signs which required 150 transformers.

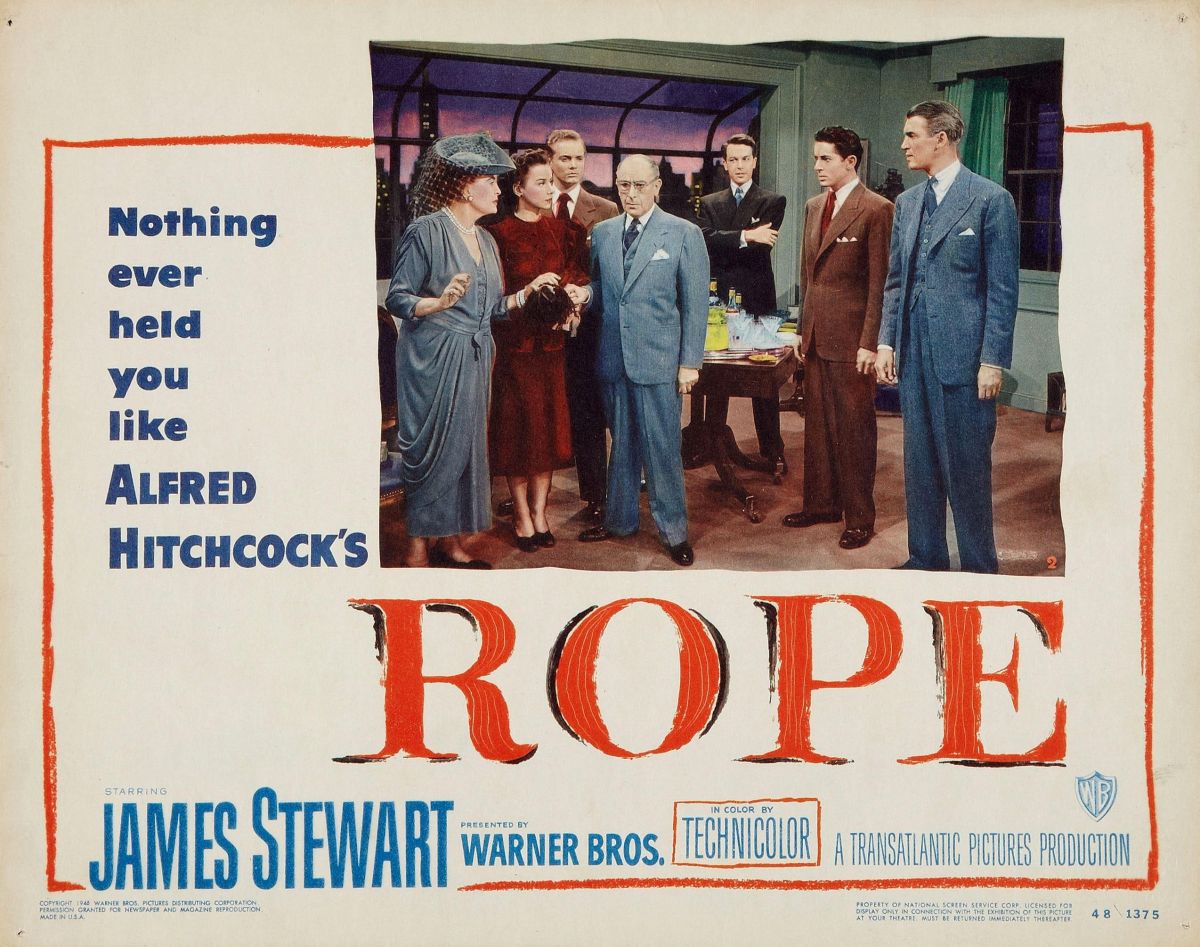

As the mechanics of the set were being ironed out, director Hitchcock rehearsed his shooting plan with his director of photography, Joe Valentine, ASC, William Skell, ASC from Technicolor, and his crew and cast of eight: Jimmy Stewart, John Dali, Farley Granger, Joan Chandler, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Constance Collier, Douglas Dick and Edith Evanson.

Hitchcock had worked out his plans to the last detail. The elapsed time of the story was one hour and 30 minutes. On the screen, the picture will run one hour and 30 minutes. The script was written without scene numbers and was first rehearsed in sections of nine minutes, because a reel of Technicolor film is never longer than 952 feet.

At the beginning of the rehearsals, Hitchcock wouldn't commit himself on how long he thought it would take to get the picture finished. His comment was, "Because of the nature of the story we shall have to rehearse it well — whereas today most actors and technicians come on a set cold.' We hope to make the shooting go quicker — much quicker.”

In the final count, the picture required 36 days, 14 in rehearsal, 2 days of tests, and 20 shooting days. After the initial rehearsals of the entire script, the cast and crew would rehearse one reel and shoot it the following day.

To watch one of the new Hitchcock-type "takes” was to watch something new under the Hollywood sun. It was like being backstage only more chaotic. For each 9-to-10-minute "take," the camera — mounted on one of David O Selznick’s pony express dollys — continuously followed the action. Actors did not rest when the camera was out of range because it would return to a different angle momentarily and they had to be in their position with new props. All of the furniture was wild. Tables and chairs were pulled away by four prop men as the camera swung through the apartment. The wild walls were pulled out of the way of the camera and then rolled back into position. Five sound men operated overhead mikes. Five more boom boys cranked their mikes into and out of position on cue. Electricians, grips and cable boys knew each move in each reel as well as the stars

To be certain that the camera dolly (riding free of any tracks) was rolled or pulled back in its right position for each angle during the long "takes,” numbered circles were tacked to the floor. One technician’s job was to indicate with a pointer the next camera position, and then give a hand cue for the grips to move the dolly to the next numbered circle. To help the grips in their ticklish chore of getting the camera exactly into position on each move, a flashlight was suspended under the camera directly under the lens. When the small circle of light which it cast on the floor was directly over the numbered circle the grips held the dolly at that position and breathed easier until their next cue.

According to Valentine, the most moves made in any one reel was 39 different angles. The least number of "takes" on any one reel was three. The most was 15.

"Our worst calamity,” said Valentine, "was the day one of the wild walls didn’t move quite fast enough and the camera went crashing right into it. The crackup jimmied the friction head of the camera and we suspended filming for the day.”

The lens used throughout the filming was a 35mm. lens which photographed everything from 2 ½ foot close-ups to long shots of 30 feet. A Selsyn motor was calibrated to the lens to insure its correct focus, and the blimp head was made especially to allow a 2 ½ foot focus.

"My biggest problem,” said Valentine, "was the lighting. Especially the job of eliminating mike and camera shadows. In the reel where we had ten mikes in operation, we had to have electricians working five dimmer panels.”

Valentine muted the color to a low key by neutralizing the set and costumes so that there were no glaring contrasts. He attempted to photograph color purely as the eye receives it. Its key use was in the sunset. Subtly employed, the yellow glare of the late afternoon sun faded to soft gray with light reflections on the moving clouds (made of spun glass), then died slowly and finally to dusk, then dark blue darkness with the lights of the city appearing in the miniature skyline.

During the final gripping moments of the story, when the body was discovered and the two killers were trapped, the set was flooded at intervals by great pulsations of red, green, and white light, which supposedly came from a huge neon “STORAGE” sign just outside the living room window. The impact of the rhythmic light changes added dramatic tension similar to a musical effect. To accomplish this, light with the different colored gelatins were fitted with shutter devices electrically operated in synchronization with the blinking of the neon sign.

The question was asked — how does this new long "take” technique affect the cast and crew? Valentine says it means more careful planning by the crew members, and will be of the greatest help to the actors. "The way we usually film a scene,” he said, "by making first a master shot, then a medium shot, and finally a closeup keeps the actors waiting endlessly. By the time we get around to the close-up the stars are exhausted and the spontaneity of the scene is lost. But with this reel-by-reel filming the actor can sustain a characterization, and maintain an even flow and pace in his work.”

To one key question — What does this do for the audience; what's the difference whether the picture is shot a reel at a time or line by line? — Hitchcock gives this answer: "The audience must never be conscious of it. If the audience is aware that the camera is performing miracles the end itself will be defeated. The camera, rolling without a single stop through the entire film, is merely an aid to the story which is full of suspense. The result I’m after is to excite the audience by making the picture flow smoother and faster.”

You’ll find our complete retrospective look at the film here.