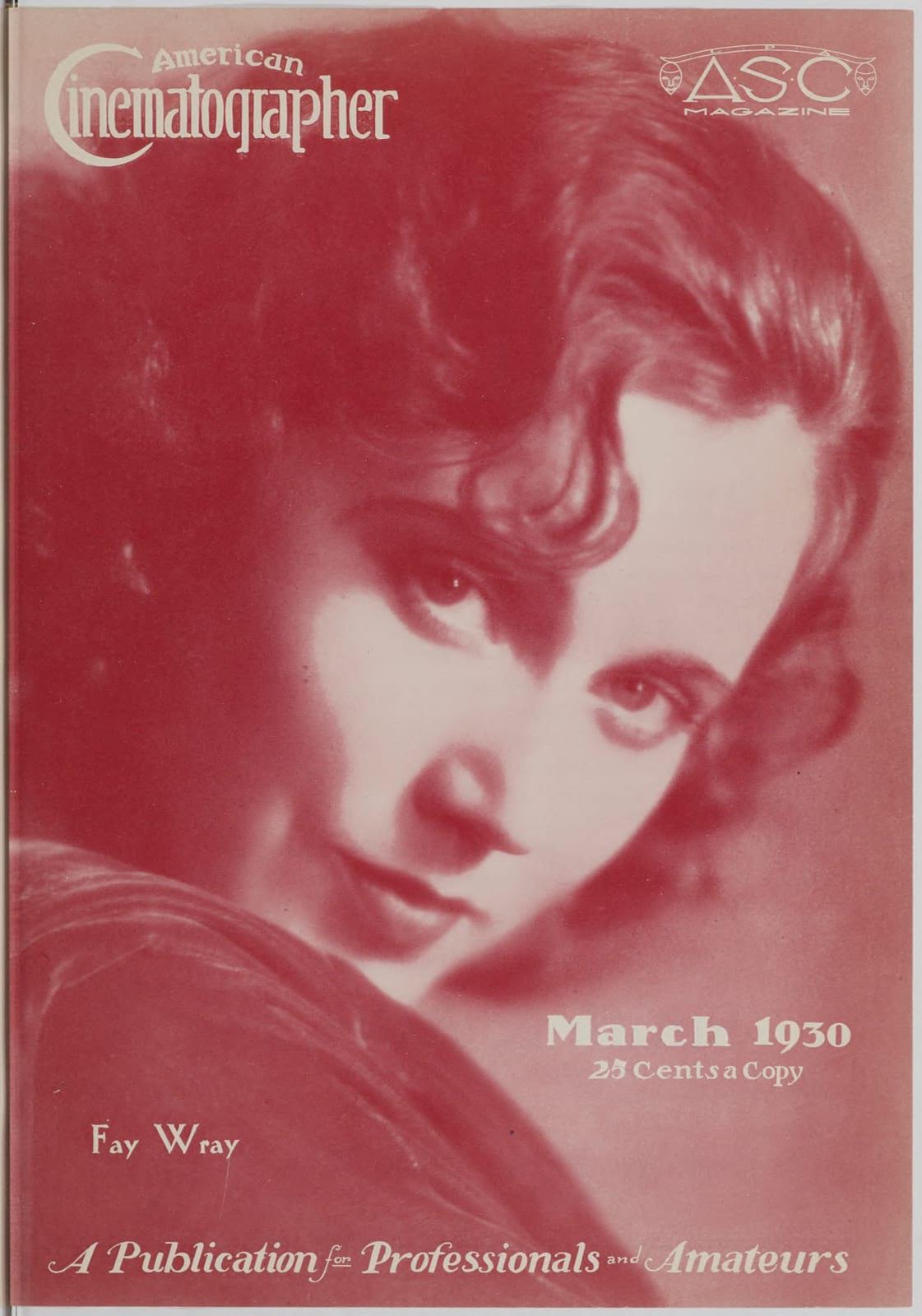

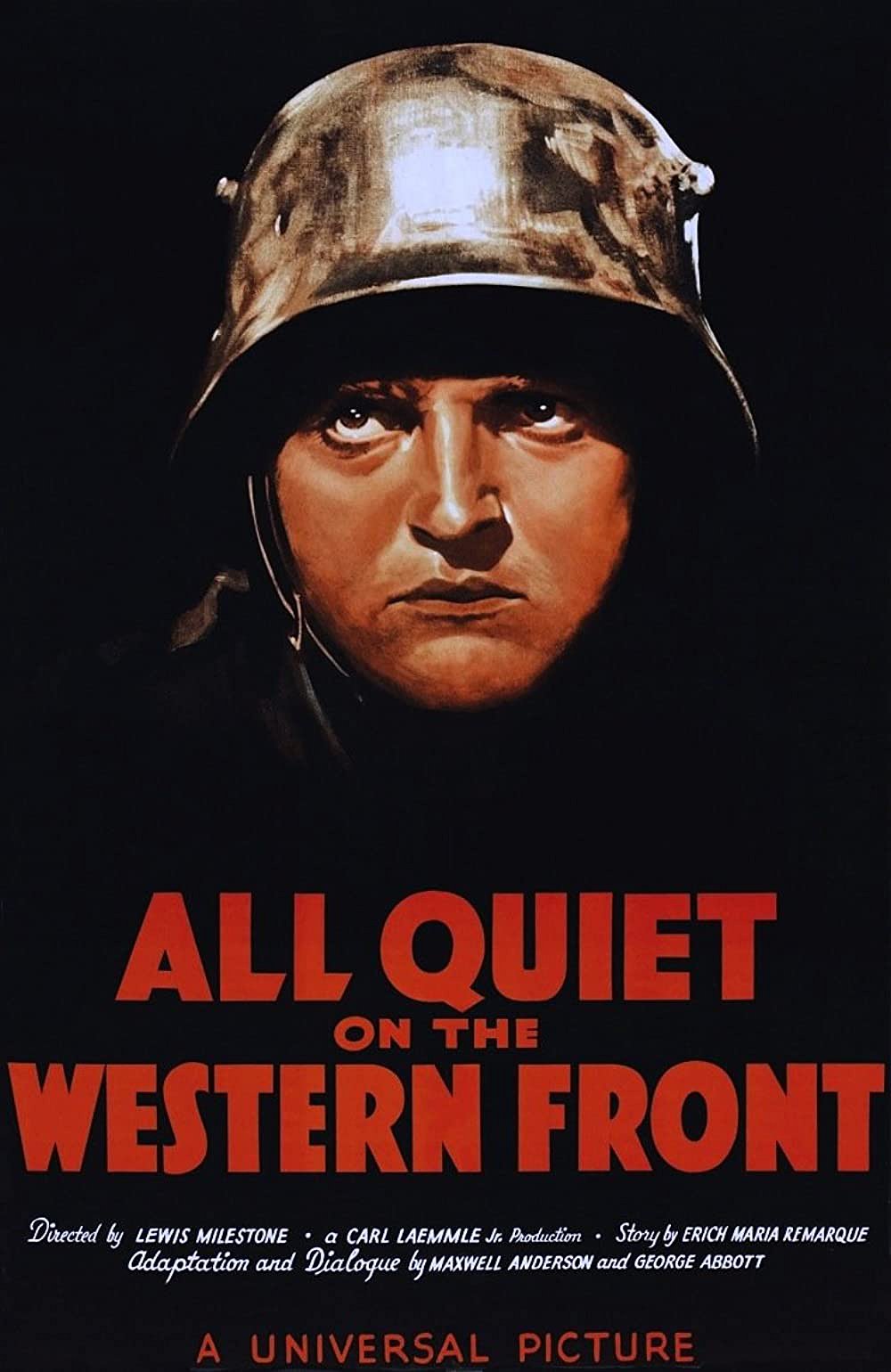

All Quiet On The Western Front: The Greatest Human Document of the War Comes to the Screen

A look back to 1930, and the reception of the film based on the 1929 novel by Erich Maria Remarque.

By Loretta K. Dean

The thunder of the guns swells to a single, heavy roar and then breaks up again into separate explosions. The dry bursts of the machine guns rattle. Above, the air teems with the invisible movement, with howls, pipings, hisses… on every yard a dead man…

“Bombardment,” says Kat.

So, Erich Remarque wrote in his magnificent book. And down near Balboa where Universal photographed the battle scenes for this great story, All Quiet On the Western Front.

The thunder of guns shook the earth... lines of soldiers picked their way across shell-pocked ground amid bursting grenades and bursting shells... a bayonet flashed... a ring of steel... a scream... then onward... slowly, almost painstakingly... A little group of mud-covered men crawled over a knoll... ten seconds later a terrific explosion and the knoll was a yawning hole... A few feet away and another blinding explosion... men dropped to the ground... burrowed their faces in the dirt like rabbits…

“My God, that fellow is lying right on the biggest charge of dynamite,” the speaker, sitting at what looked like a huge keyboard, pulled his finger back with a jerk as he was about to push a button which would have blown the unsuspecting soldier to Eternity. Practiced eye gazed across the battlefield... another button was pushed... another blinding explosion and another yawning hole only a few yards from a group of soldiers who were buried with the earth spewed up by the exploding dynamite.

Twenty acres of land turned into a perfect replica of the battlefield at the height of the war. A thousand men struggling as they struggled then. Barbed wire, rusted and tangled; bits of torn uniform caught here and there — men had died there... that is evident. Mud... puddles of dirty water. Dead and dying men sprawled about in grotesque positions. Some men sombre, others laughing in the face of death.

Realistic... so much so as to make you turn away at times thinking perhaps the genius at the dynamite keyboard had made an error.

And... scattered about in spots that gave the best results were the cameras and cameramen. Shells flew close overhead, screaming by like messengers from Hell. But the cameramen didn't seem to notice them. Didn’t seem to notice the clouds of dirt that sometimes showered down about them. These cameramen are really remarkable chaps. They talk little; get little credit; but what genius is theirs! What would such scenes as those mentioned above amount to without their cleverness! Just a lot of noise and wasted effort.

While the cannons roared and shells flew and dynamite exploded, a quiet-mannered man stood near Director Lewis Milestone. He seemed at the moment unconcerned. But a short time before, when the preparations were being made for the great scene that was being filmed, this man was a bundle of action. He was here, there, everywhere, and it was his judgment which decided that a camera would be here, another there, another in this place, another in that. This man was Arthur Edeson, ASC, director of cinematography on the picture; a master cameraman of long experience.

Making the battle scenes of this picture was really a remarkable piece of work. War pictures have been done so well that whenever a producer decides to make one he is immediately faced with something mighty big to shoot at. Each picture simply must be better than the one before — otherwise it is a failure.

So Universal had a big job ahead when they decided to start this great war story. Weeks were spent in preparing the ground for the battlefield. And when it was finished it looked as though someone had transplanted a section of that Western Front to California. Experts, men who had been “over there,” planned it. German guns were brought across the Atlantic and then across the Continent just for the picture. Trenches were dug and the 20 acres were mined and planted with dynamite. This alone was a stupendous task. Fine wires led from every charge to the big switchboard back of the lines. Every charge meant certain death to perhaps a score of men if the man at the switchboard made a mistake.

So, days were spent in rehearsing. The men were sent forward in waves. They were told exactly where to stop at certain counts, and who was to die and where and when they were to fall.

“You drop dead here,” explained an assistant director. “You drop over there... and you, here, crouch down here and the blast will...”

And then the battle was begun. Back at the switchboard the operator sat quiet and unruffled. Suddenly he would reach out and press a button. There would be an explosion and earth would fly behind a group of men. A mistake of two seconds and there would have been real death.

So realistic were the battle scenes that great care was taken in the hiring of the men for the jobs of soldiers. No man was taken who had been shell-shocked in the World War. One got by. He was taken to a hospital the first day. The screaming shells were too much for him.

As remarkable as the uncanny work of the dynamite man was the work of the cameramen who were getting the spectacular and the closeup. Close-ups of poor devils, who, with faces as pale as turnips, clenched hands and whimpered softly for the mothers who cuddled them as babies... You cannot describe it adequately. You have to see it.

This picture should be a masterpiece. And its realism is so great, its story so powerful, the suffering of the youth of the world so graphically portrayed and photographed that if enough mothers see it, they may exert a force that will prevent such future scenes in real life as this picture shows. From the point of view of story, direction and cinematography, Universal has a picture that should go down as one of the greatest war pictures ever filmed.

Edeson was one of 15 founding members of the ASC in 1919 and would go on to shoot such films as Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, Sergeant York, The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.

You’ll find our complete production story on the 2022 feature adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front — shot by James Friend, ASC, BSC — here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.