American Psycho: 25th Anniversary

A look back at the controversial production that polarized audiences and became a satirical indie classic.

Editor’s note: The following is our reporting that was originally published in AC April, 2000 on this infamous satire of 1980s yuppie consumer culture, which had its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival of that same year and opened theatrically on April 14. It's followed by a curated collection of production photos by unit photographer Kerry Hayes, SMPSP.

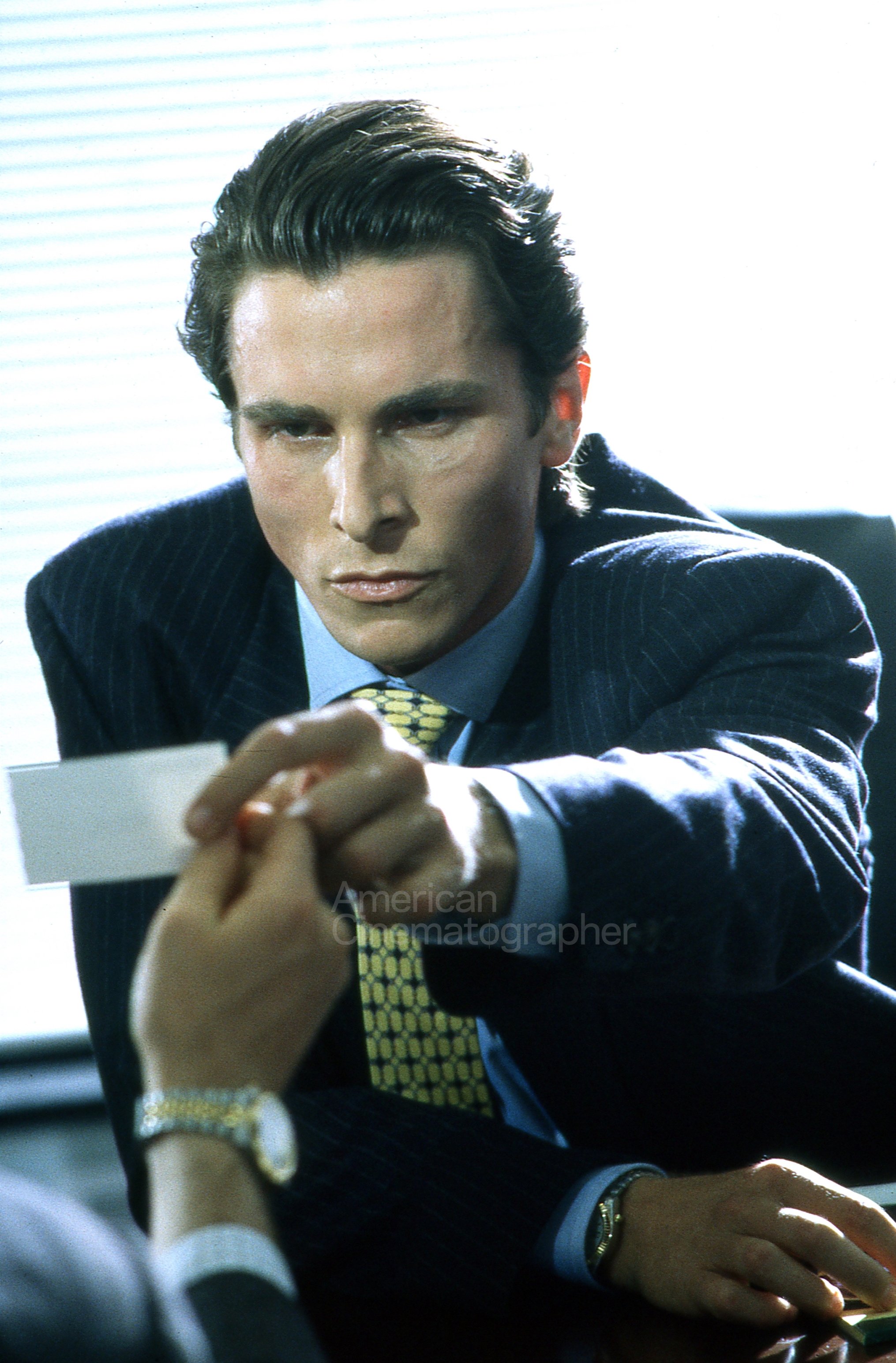

The love-it-or-hate-it entry at this year’s Sundance Festival was American Psycho, based on bad-boy author Bret Easton Ellis’ controversial 1991 novel about Patrick Bateman, a young Wall Street trader with a penchant for designer suits, trendy restaurants and unusually ugly acts of homicide — including the maiming and mutilation of women.

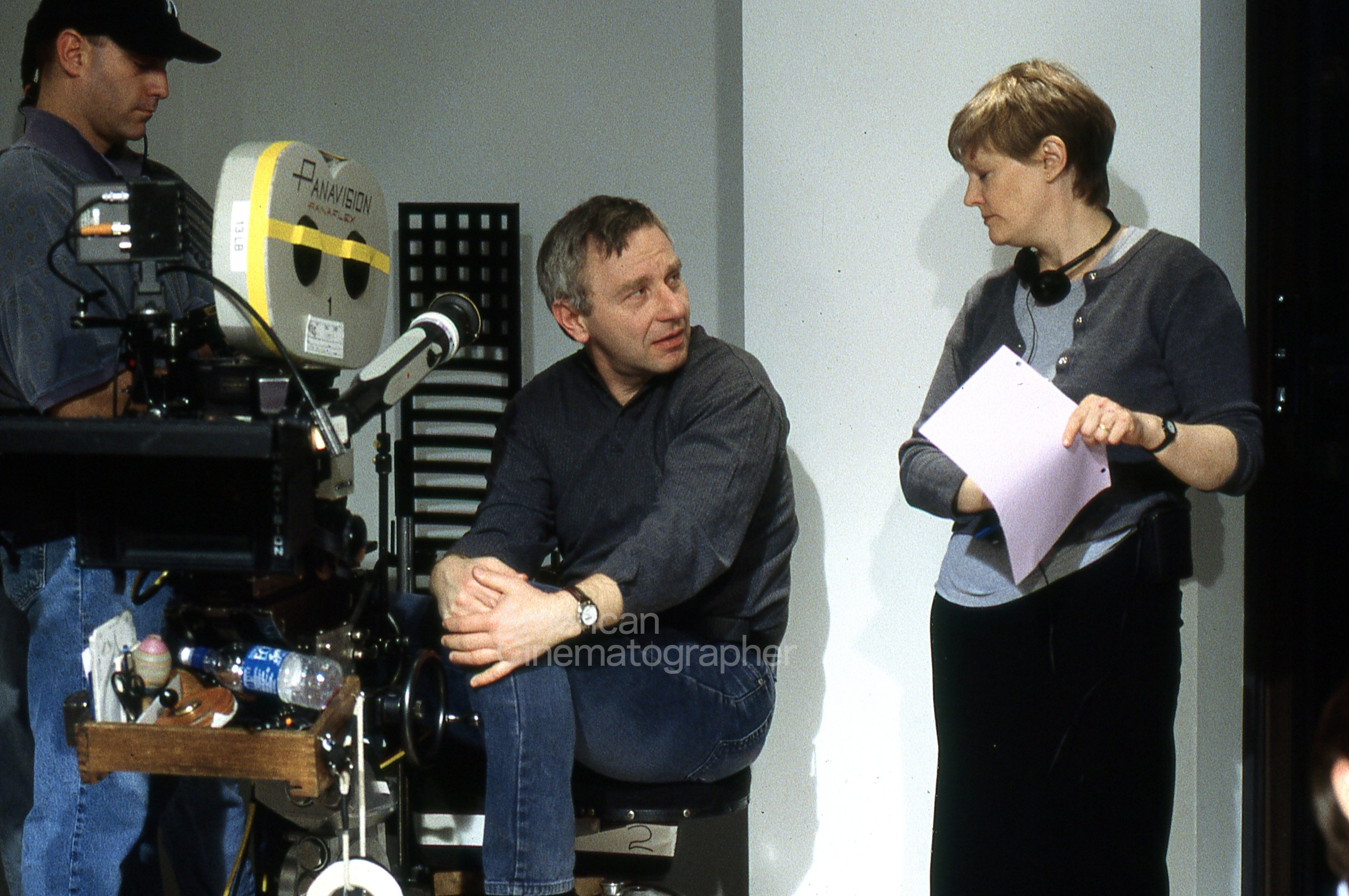

The novel’s defenders praised it as a biting satire about the greed and narcissism of the yuppified 1980s. Certainly, that is how writer-director Mary Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol) and co-writer Guinevere Turner elected to play it in their screen adaptation. “It’s not a naturalistic story; it’s a black comedy,” asserts Harron, who kept the book’s most explicit violence offscreen.

“I wanted a cool tone I looked at a number of Kubrick and Polanski films from the 1970s, in which the stories were about unease in a space. You have a very composed, perfect surface, and then something frightening and uneasy happens within that world.”

— writer-director Mary Harron

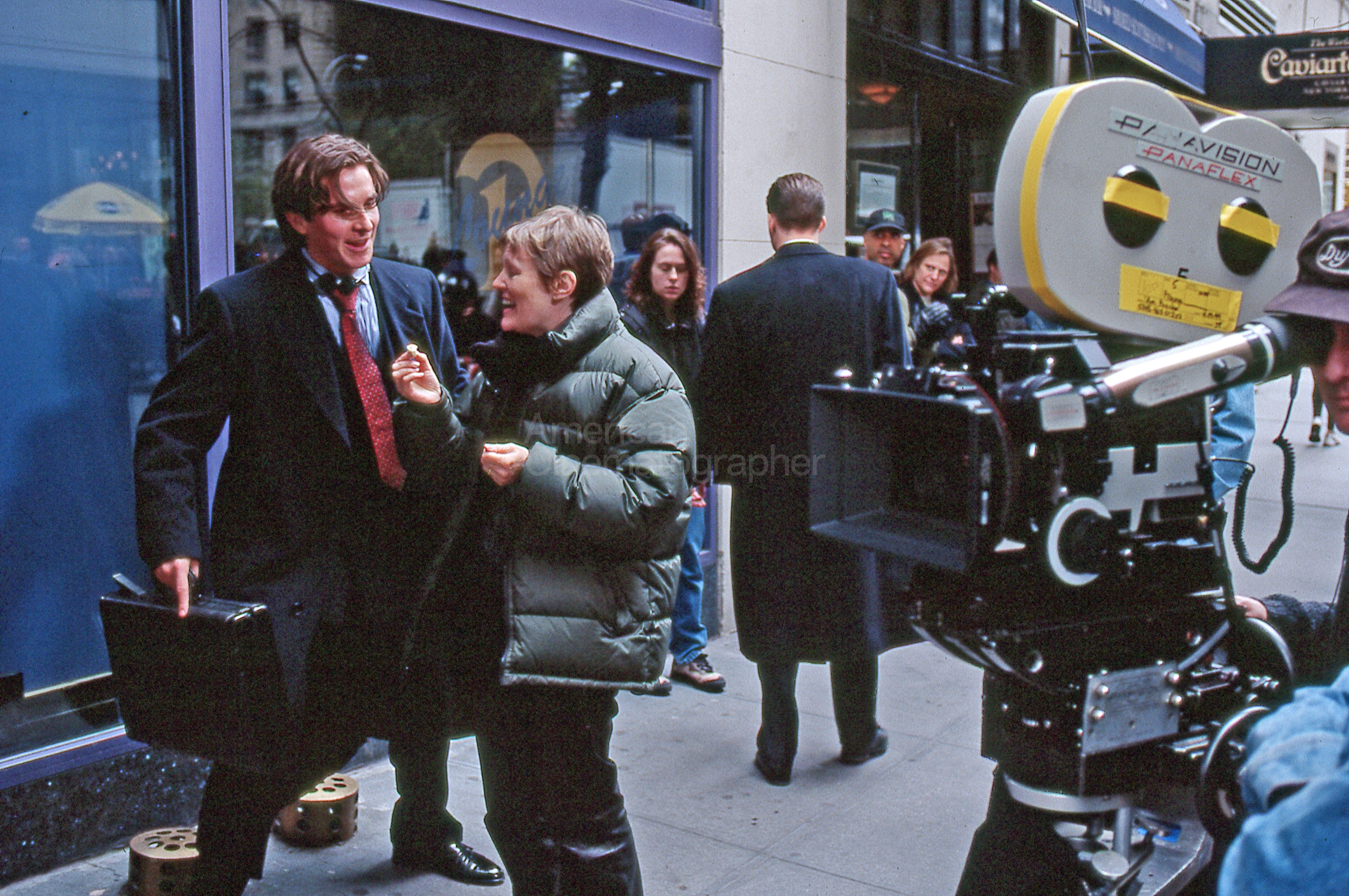

That didn’t seem to matter to protesters in Toronto (which was standing in for Manhattan), who raised such a fuss over the film being shot there that just days before production was to commence, several promised shooting sites suddenly became unavailable. The 11th-hour cancellations proved a blessing in disguise for cinematographer Andrzej Sekula (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Hackers, Cousin Bette), because a set offers far more control than almost any practical location.

“Nearly 30 percent of the film takes place in Bateman’s office, and it would have been impossible to light or move the camera around the way we wanted to at a practical location.”

— cinematographer Andrzej Sekula

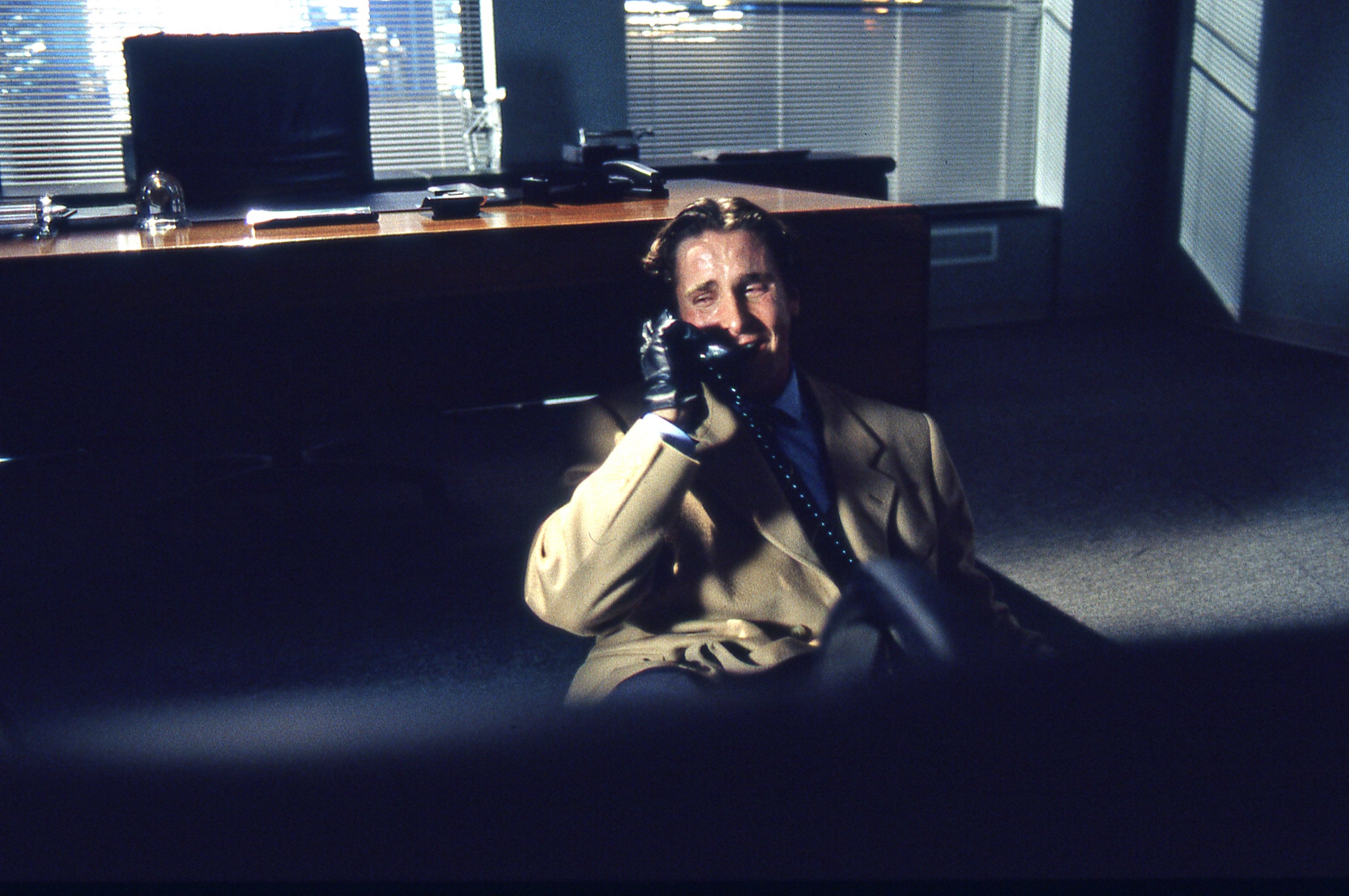

This proved especially true when it came to one of the film’s key locations: the high-rise office where Bateman (Christian Bale) plies his unspecified trade. “Nearly 30 percent of the film takes place in Bateman’s office, and it would have been impossible to light or move the camera around the way we wanted to at a practical location,” Sekula concedes. “We built panels in the ceiling, and above the panel we built a grid from which lights could be lowered. I could pull the lights back up and close the panels when the camera showed the ceiling in the shot, which happened frequently because I used a lot of wide-angle lenses.”

Small units adorned the grid: 575s, 1200s and 2500s. Primary light for the set, however, came from 18Ks placed outside the window to simulate the sun. Sekula credits gaffer Franco Tata and grip Chris Faulkner with designing an elaborate system for positioning the lights. “We couldn’t [position lamps directly] outside the window because they would show in the shot,” explains Tata, speaking from his home in Toronto. “Instead, we suspended the 18Ks from an 80'-long box truss, just above the frame line. Because each 18K with cables weighs about 200 pounds — and we were using six to eight of them — we had to suspend the truss with chains and motors. A remote switch allowed us to raise and lower the lights and manipulate them at our discretion. It worked amazingly well, because it allowed Andrzej to do the shots he wanted, which included a lot of 180s.”

For a scene in which a police helicopter shines a searchlight into Bateman’s office window, an electrician sat on a wooden platform that had been built onto the truss and manually jostled a 6K CinePar. “We couldn’t afford to hire a helicopter, but by shining a light through the window and adding the sound of one, we conveyed that Bateman was on the run from the police,” says Sekula.

An 80'-long TransLite of the New York City skyline was hung outside the window. Actually, two TransLites were employed on the picture: the first was a day scene, and the second was the same scene at night. The box truss was positioned between the TransLite and the window. Another six 18Ks were set up behind the TransLite. These were turned on for both day and nighttime sequences. However, only one or two of the lights on the box truss were employed for the night sequences. Full CTO gels were added to all of the HMIs for the filming of night scenes.

The Polish-born Sekula came to cinematography via still photography. Repeatedly denied admission to film school in Poland (during the 1970s, political connections frequently counted more than talent), he was accepted at Britain’s prestigious National Film School. A year after graduating, he hooked up with a first-time American director named Quentin Tarantino, shooting Reservoir Dogs and then Pulp Fiction.

Harron had admired Sekula’s work with Tarantino, and told him she wanted a similarly hyper-realistic look — very bright and crisp, with deep focus. “In a way, I wanted the antithesis of the David Fincher school of photography, which is very imitated right now,” she explains. “In Fincher’s films, it’s very murky, kind of Gothic. But it’s not right for black comedy, where you want everything to be really crisp.”

That suited her director of photography just fine. “If images are clear, they become three-dimensional,” Sekula notes. “People say Reservoir Dogs is very violent. It is, but the violence makes such an impression because the screen is so sharp.”

Sekula used the same film stock on American Psycho that he had employed on Reservoir Dogs: 50 ASA Kodak EXR 5245. (He also used Vision 250D 5246 for a couple of short driving sequences.) He shot both pictures in Super 35. “When you use Super 35, the film becomes one big optical, so it’s really important to have good image quality,” he cautions. “That’s one reason I used a slow stock. With 5245, I get maximum sharpness, best color saturation and the smallest grain. If you use faster film, the grain becomes huge in the post optical.”

Sekula opted for Super 35 over anamorphic mainly because spherical lenses offer greater depth of field. He intended to use wide-angle lenses as much as possible to help attain a three-dimensional look. “Even when shooting tight, I used wide-angle lenses [primarily 17.5mm, 21mm and 24mm], because you see much more of the background and it is still in focus. I shot at around T4; that way, even when forgoing a strict POV from the actor’s perspective, you still get a sense of the surroundings, which helps show how the characters relate to their environment.”

The camera package consisted of two Panavision Platinums, a set of Primo primes and a Primo 4:1 17-75mm zoom. “Panavision has superior lenses, with minimum distortion,” the cinematographer enthuses. “Even their 14.5mm has almost no distortion.”

The slow stock required a lot of light, and Sekula relied heavily on HMIs, often balanced with half CTOs to warm them up a bit. The most colorful scene was a wild nightclub sequence (set in the larger of the two nightclubs Bateman visits), which got its pronounced red hue from Primary Red (Lee 26) and Yellow (104) gels mounted on 6K CinePars and 18Ks. Sekula lent the second nightclub a bluish tint by substituting Peacock (Lee 115), medium Blue-Green (116) and dark Yellow-Green (090) gels. Putting gels on 18Ks isn’t easy because they have a tendency to burn through, but Canadian rental houses stock a kind of frame holder called a Dumb-Dumb that attaches to the ears of the light and extends the frame so it sits out three or four feet from the lens.

For the larger nightclub sequence, the camera was mounted on a Titan crane and aimed down at the tops of the dancers’ heads, and then tilted up until it was level with a balcony where other patrons were sitting. A disco ball hung from the ceiling, with 6K Pars shining directly into it from the dance floor. (The lights were hidden by dancers.) For certain shots, the lights were positioned behind the camera, shining directly into the mirrored ball. Whenever the camera was moved for another setup, the ball was also moved. “We just went with bare bulbs, which makes the light extremely spotty and hard,” recalls Tata. “Once the light hits the ball, however, it spreads light everywhere, producing a great mirror-ball effect. Normally, you would hit those balls with a much smaller light, but since Andrzej was shooting 50 ASA we needed four to eight times more light. We used everything we had.”

The trickiest shot in the film was a short nighttime exterior sequence in which Bateman, pursued by police, exits from a high-rise and runs through an outdoor courtyard into a second building. Shot on a practical location in Toronto, the scene features skyscrapers visible in the distance between the two buildings. Even if the filmmakers had switched to faster film, which Sekula didn’t want to do, there wouldn’t have been enough light for exposure. “We’d have had to prolong the exposure, but if we’d done that, the figure of Bateman would have blurred,” notes the cameraman. “Instead, I locked the camera on a tripod, covered the lower part of it with a piece of black foil stuck on with gaffer’s tape — I just looked through the camera until Christian Bale was covered in the frame — and ran the film at one frame per second. After exposing the film like that, I rolled it back in the camera, removed the matte, lit Christian and the ground around him and ran the film again, this time at the normal 24 fps, as he ran across the courtyard. The camera remained locked.” With a laugh, he adds, “If you focus really carefully at the distant windows, you will see some strange pulsing, but nobody will notice unless you say, ‘Look at that particular spot.’”

Camera operater/second-unit director of photography Paul Boucher shot a fair portion of the film handheld while sitting on a dolly. Sekula explains that this technique “gave us the texture of handheld, but the movement was very smooth. The shots became more like POVs.” The method was frequently employed just before and while Bateman committed a murder.

American Psycho is a dialogue-heavy film; several scenes find Bateman and two or three other characters sitting and talking in a restaurant, his apartment or office. Harron didn’t want a kinetic camera style, but Sekula tried to keep the camera moving in subtle ways by designing long, flowing tracking shots which gave the camera a kind of voyeuristic intensity. He acknowledges that few of those shots made it into the film intact.

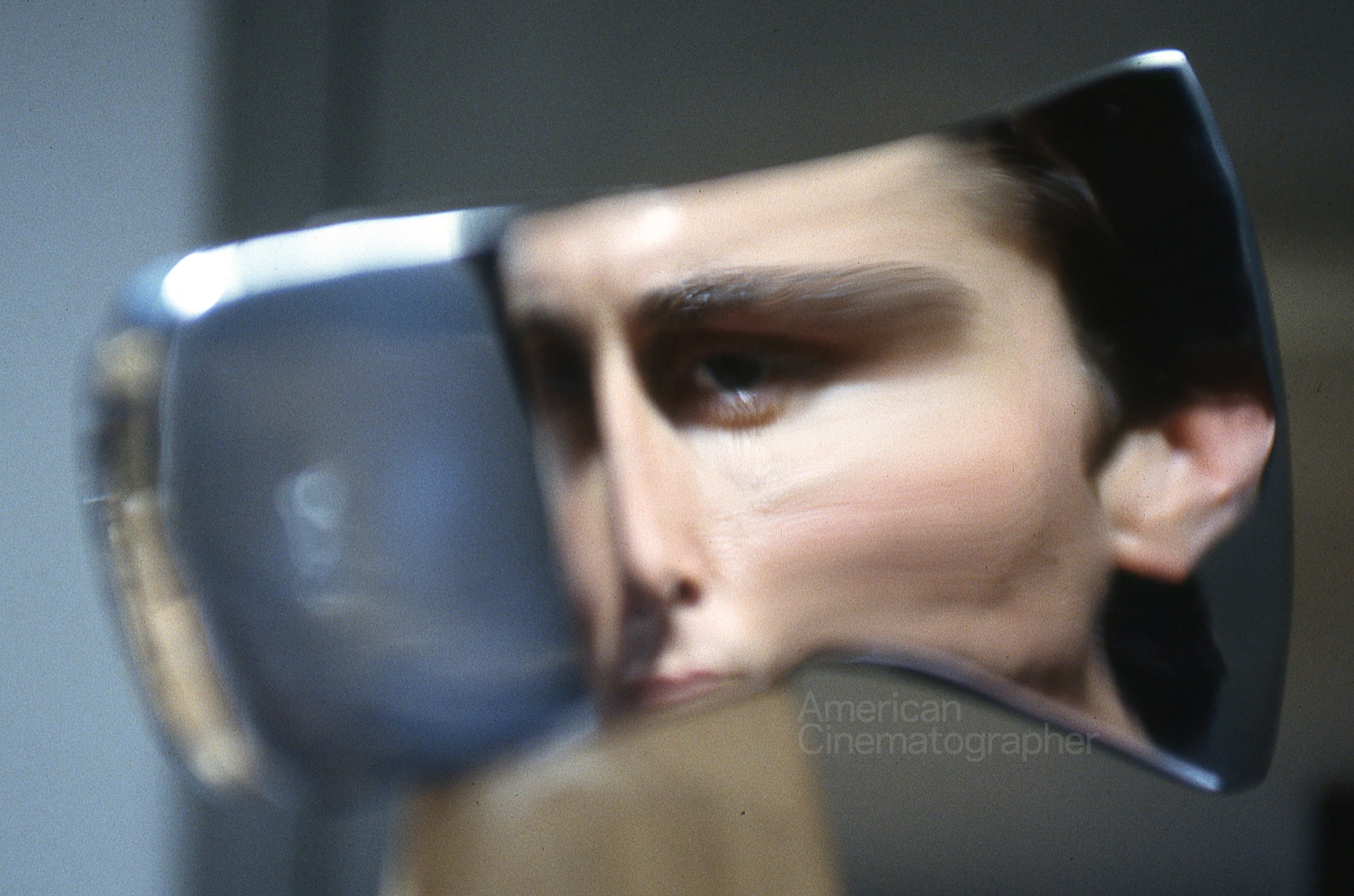

In the end, Harron opted for an even more static style. “I wanted a cool tone,” she explains. “I looked at a number of Kubrick and Polanski films from the 1970s, in which the stories were about unease in a space. You have a very composed, perfect surface, and then something frightening and uneasy happens within that world. It’s about tension more than violence, and being static somehow makes it more nerve-wracking.”

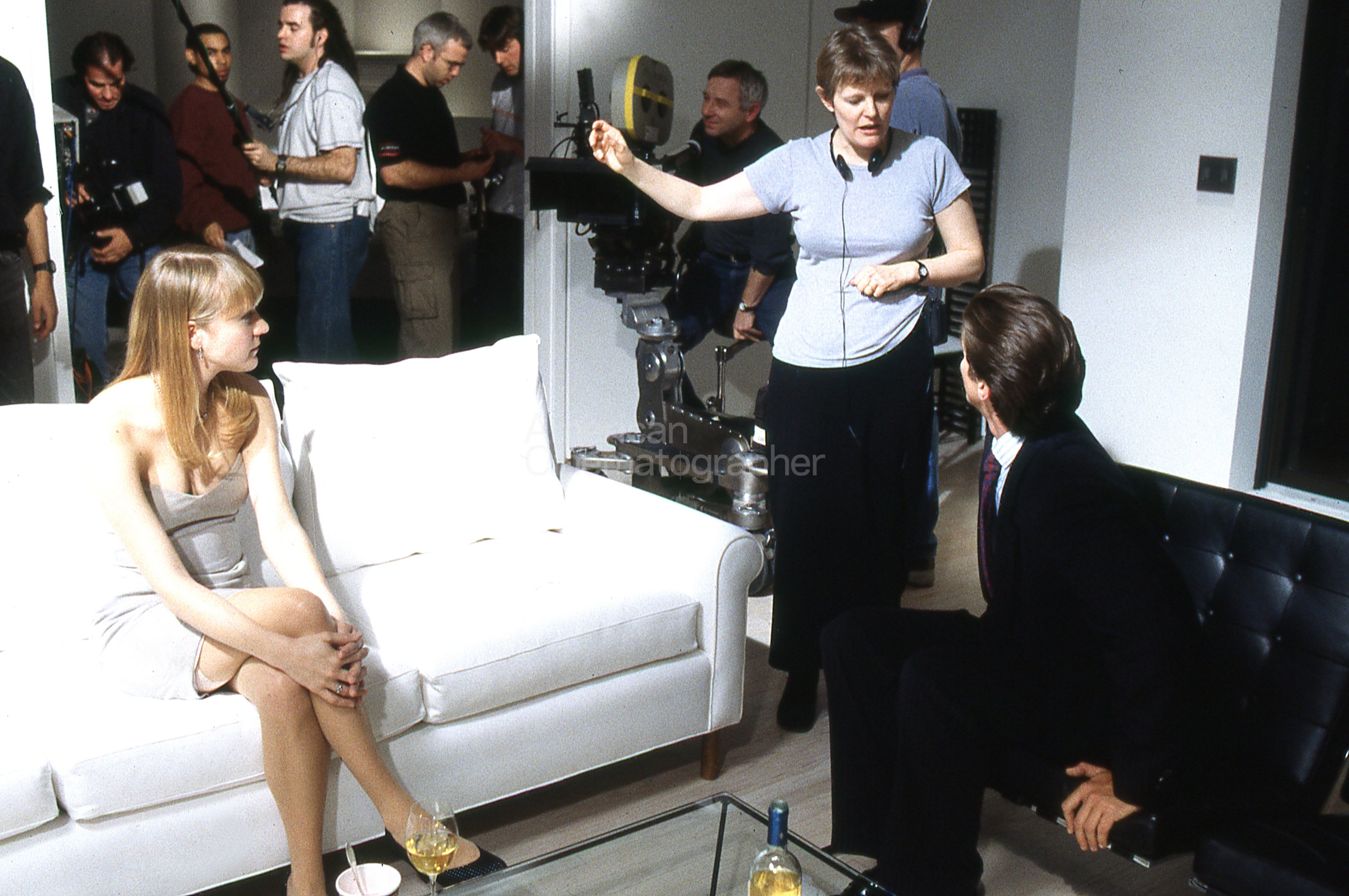

Shooting the scene in which Bateman invites his secretary, Jean (Chloë Sevigny), to his stylish apartment, where he intends to kill her.

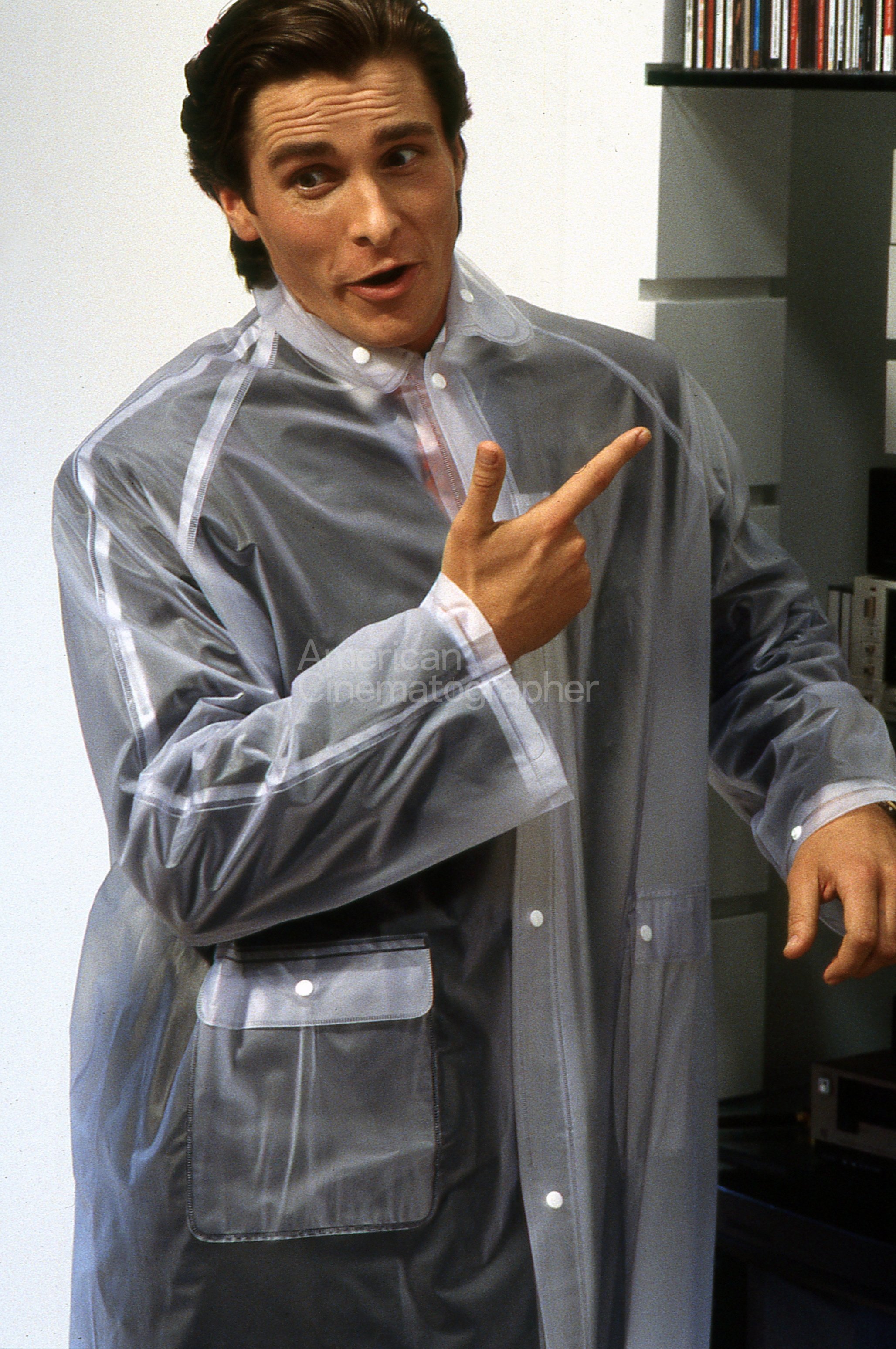

After Bateman lures rival Paul Allen (Jared Leto) to his apartment, he first disarms him with small talk.

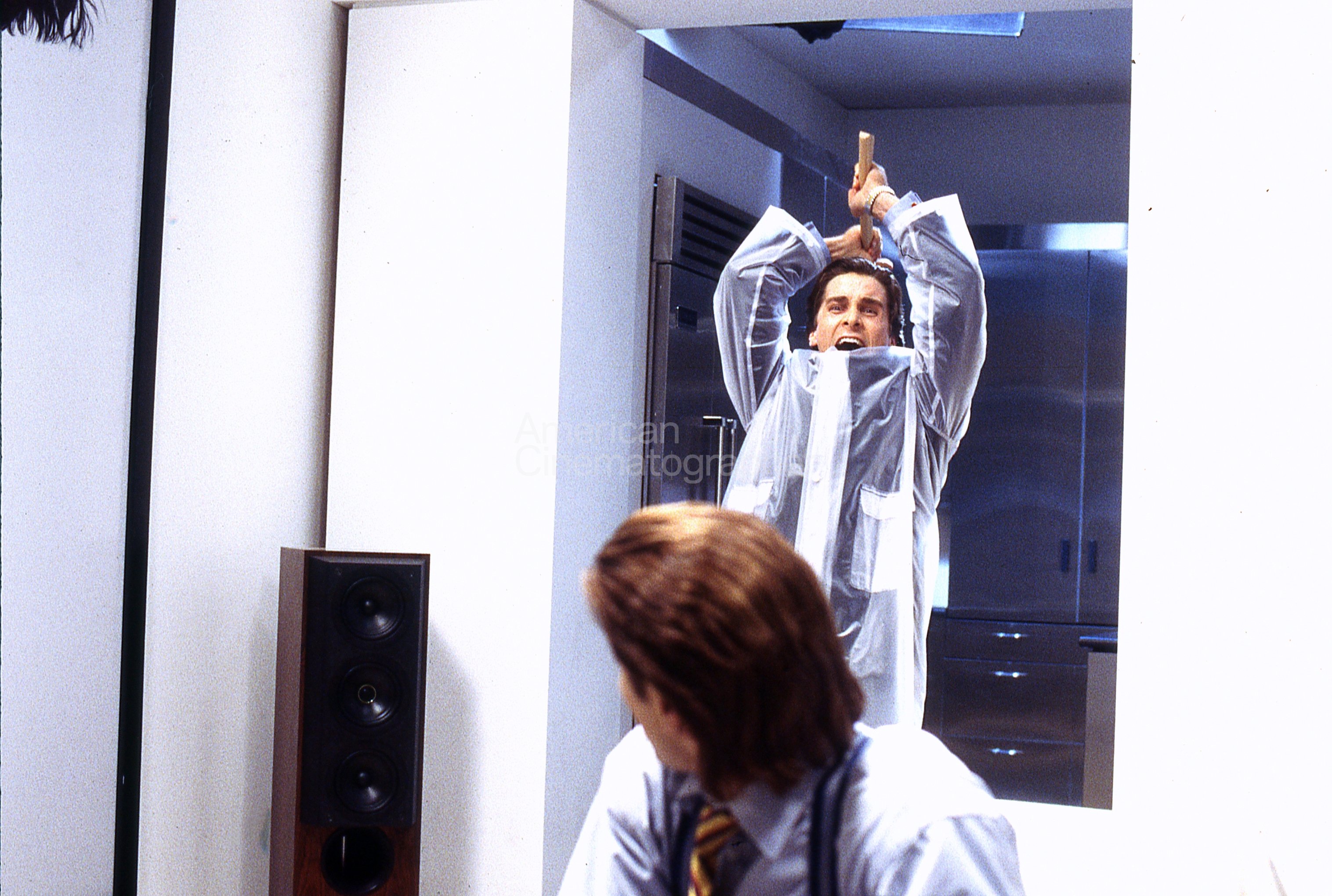

Bateman solicits a prostitute and takes her back to his lair, ending in one of the film‘s most disturbing scenes.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.