Filming Anatomy of a Murder in the Story’s Actual Locale

Limited working space and restricted lighting accommodations made the location shooting for this production a real photographic challenge.

This article originally appeared in AC, July 1959

A passion for authenticity and realism, two highly desirable qualities in motion pictures, brought producer-director Otto Preminger and his production crew to Upper Michigan to shoot Anatomy of a Murder, a story long at the top of “best seller” lists.

When I first heard of the plan in Hollywood, it seemed exciting and laudable. For nothing enhances the realism of a motion picture so much as staging and photographing its action away from Hollywood on actual locales.

We would be shooting, I was told, in the 57-year-old Marquette County courthouse — a stately and attractive building — and also in the actual home of the author of the novel, Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker, as well as in and around other sites in the locality.

The courtroom, we discovered, when we made our initial visit of inspection, had been built by men who took great pride in their work, determined that it would not fall apart at the seams. The walls were thick and solid — not one of them “wild” — and there was considerable dark woodwork; and above, a magnificent stained-glass dome.

Pictorially, all this was wonderful. But to hang lights here in the standard overhead set-lighting fashion was obviously out of the question. Moreover, we would not be allowed to nail anything to the smooth plaster walls. Obviously, we had a major lighting problem on our hands.

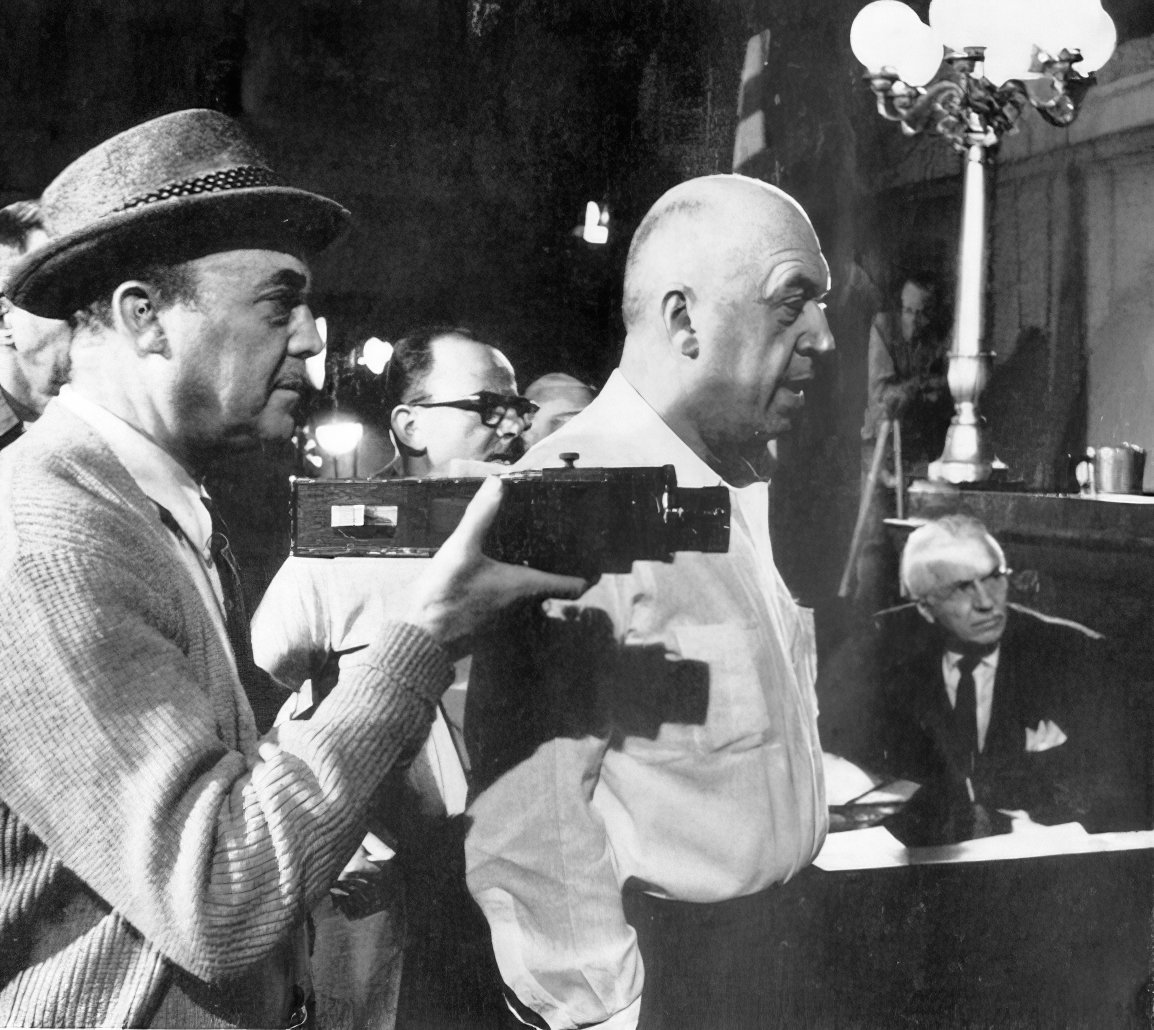

Mr. Preminger places great emphasis on the dramatic possibilities of the “fluid” camera, and in this production — and especially for the sequences that were to be shot in the courtroom — it was to be utilized to the utmost, constantly moving in and upon his players, retreating, lateralling, reversing its field, and covering some action in a full 180-degree swing of the boom. This photographic pattern plus the fact the court room was only 40 x 50 feet in extent, made the placement of lights, dimmer banks, camera crane and other equipment something of a problem.

Directly complicating the moving camera problem in the court room was the fact that much of the limited room area was taken up by the judge’s bench, the jury box, the two attorney’s tables, and the spectator’s area which occupied a major portion of it. For one shot here we made fifteen separate camera moves — a tribute to the ingenuity of my wonderfully inventive camera crew.

A major problem, of course, in filming these scenes, which involved six principals and some 200 extras, was getting the right balance in the lighting. Good lighting results were obtained when shooting close and medium shots here by placing lights in the court room balcony. But for long shots, taking in almost the entire court room, the physical limitations of the room prevented the use of cross lights.

When the company moved to Judge Voelker’s home to film the scenes scheduled there, we found conditions quite cozy. The largest room in this 80-year-old residence was a scant 10 x 12 feet. Into this room we somehow managed to get James Stewart, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, a piano, the camera, lights, and what crew members did not mind standing on one another’s toes. Mr. Preminger, as I recall, directed the scene from the doorway of an adjoining room.

Probably the most ingenious shot we made on this location was a moving car shot without benefit of a conventional camera car. And because we had brought no vehicle along for making shots of this kind in the streets (the scene was written into the script on location) we looked about for a suitable camera carrier. Luckily we found a “low-bed” truck designed for moving heavy machinery, the bed of which, as its name implies, being about 15 inches from the ground. On this we mounted camera, tripod, lights, sound recorder, and crew. The “low-bed” was then hitched to a prime mover which in turn was connected to a portable generator, and away we went. Rube Goldberg would have envied this incongruous assembly, but it enabled us to get the shot.

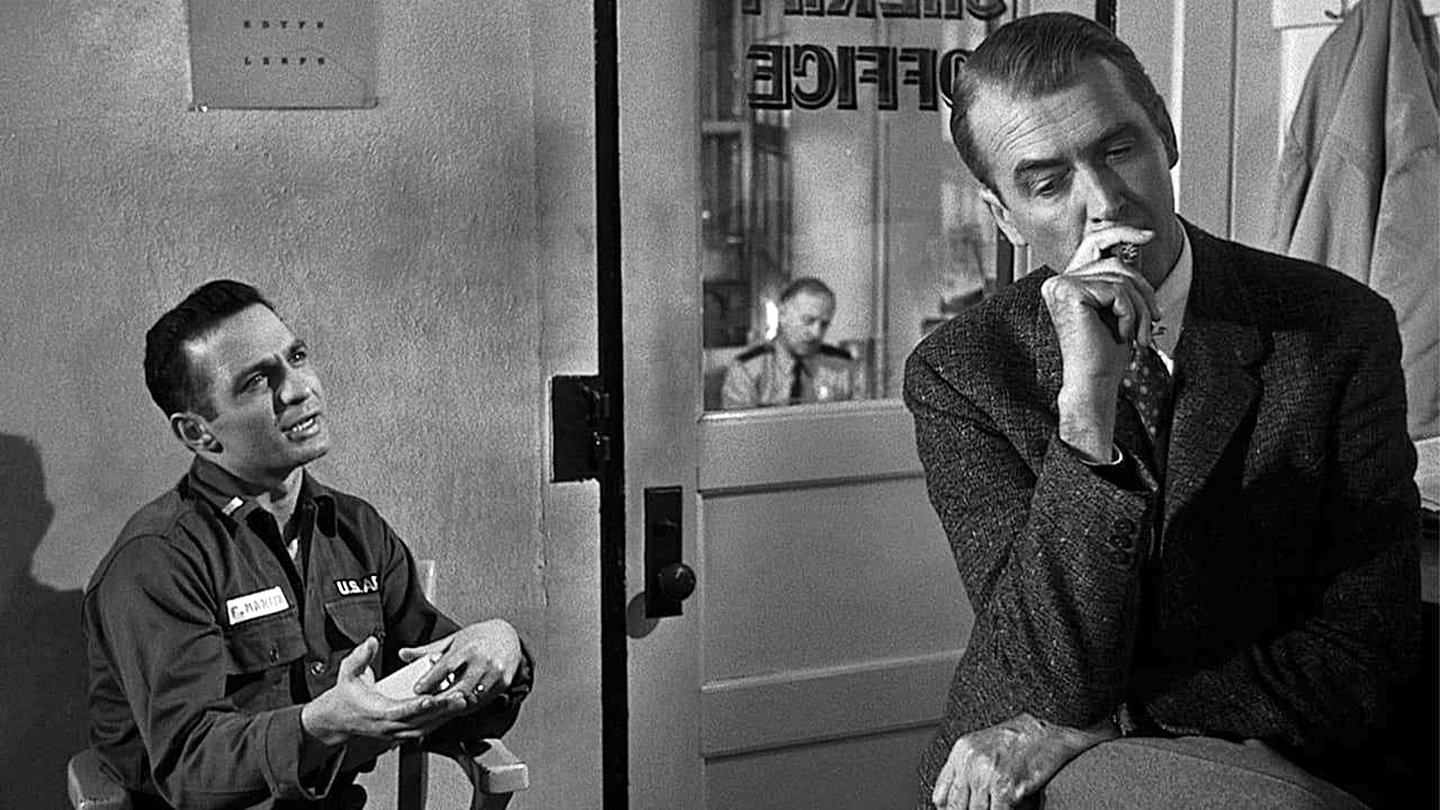

The most difficult scenes to film, perhaps, were those staged in the local County Jail. The action took place in a small cell, too narrow even to permit the entrance of a crab dolly. But the problem was soon licked by our grips who whipped up a wooden dolly barely 30 inches in width. A wag, observing the situation, quipped: “Why not just release the prisoners?”

Lest it be construed that we shot entirely indoors on this location. I’d like to mention one scene we shot on the shores of Lake Superior, where we utilized probably the heaviest and the greatest number of props ever introduced in a single shot. The site was a small hot dog stand. The scene itself was simple: Jimmy Stewart and Arthur O’Connell eating hard boiled eggs. However, in order to give it “production,” Mr. Preminger asked for and got in the background an overhead iron ore loading crane, a diesel locomotive and eight cars, and 17 automobiles — indicative of the wonderful cooperation we received from everyone on this Michigan location.

A flock of seagulls added further authenticity to the scene. These gullible extras were lured into camera range with 30 pounds of fish scattered along the waterfront, and performed perfectly on cue. Sort of “worked for scale,” you might say.