In Memoriam: Owen Roizman, ASC (1936-2023)

The cinematographer is remembered not only for exceptional artistry — with credits including The French Connection, The Exorcist and Network — but his grounded creative approach.

One of the most influential cinematographers to emerge in the 1970s, Owen Roizman, ASC died on January 6 at the age of 86 following a lengthy illness.

His camerawork earned him numerous honors, including five Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography, for the films The French Connection (1971), The Exorcist (1973), Network (1976), Tootsie (1982) and Wyatt Earp (1994).

In 2017, he was presented with an Honorary Oscar not only for his artistic achievements, but his role as a member of the AMPAS Board of Governors, representing the Cinematographers Branch from 2002 to 2011.

His other feature credits include The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight; Play It Again, Sam; The Heartbreak Kid; The Taking of Pelham One Two Three; The Stepford Wives; Three Days of the Condor; The Return of a Man Called Horse; Straight Time; The Electric Horseman; The Black Marble; True Confessions; Absence of Malice; Taps; Visionquest; I Love You to Death; Grand Canyon; Havana and French Kiss.

“So many times I’ve sat and looked at somebody else’s work and thought, ‘I don’t know if I could have done that. I’m not sure I know as much as people think I do.’”

But a life and career is much more than a list of credits, and here the cinematographer discusses his influences, inspirations and those who helped and challenged him along the way.

Roizman’s pursuit of personal excellence began during his youth while growing up in Brooklyn, NY, where he was born on Sept. 22, 1936. “I loved baseball and was fortunate that I was a gifted athlete,” he said, recalling his days as an all-scholastic player in high school. But Roizman also performed despite the effects of polio, which first affected him at the age of 13 and ultimately ended his promising sports career. “Theoretically, the injury that kept me out of professional baseball was to my arm, which happened during my last game in high school while pitching a no-hitter,” he said. “But it was really the polio that kept me out of the big leagues.”

While that dream ended, Roizman’s desire to excel did not, though it took some time before he found a new purpose. In hindsight, however, his calling was seemingly under his nose all the while.

For 22 years, Sol Roizman, a father of four, was a cinematographer for Fox Movietone News. And while this must have seemed an exciting profession to some, it didn’t have much impact on young Owen. “I never paid attention to what my father did because I was in my own world — I’d eat, sleep and breathe sports,” Roizman said. “To me, my father was someone who did dangerous work. I remember him telling us about the death-defying acts he would do just to get some shots — like walking the framework at the top of St. Patrick’s cathedral in New York City.

“And he was always traveling or getting called off suddenly. During the war, of course, there were a lot of emergency calls to do newsreel stuff. He missed a lot of events in our lives as we grew up. That was something I was able to relate to when my son Erik was growing up during the times I had to be away [on location].

“When we went to the movies, we always watched the Movietone News to try to figure out what my father might have shot. He sometimes filmed the family in certain situations to get some footage for what he was doing in the newsreel. Recently, somebody called me from Fox News and said, ‘I’ve got a shot of a woman working in a kitchen and then shopping in a butcher shop. Your father’s name is on the footage, so I wondered if this was a relative of some kind.’ I went over, looked at the footage, and it was my mother. There was also a shot of my aunt, her sister. This was during the war and my father had included them in a piece he did on food rationing.”

“Becoming an assistant sounded like a better opportunity... But my father was against the idea.”

Roizman’s own interest in photography at the time began and ended with “taking a few snapshots, or occasionally shooting some home movies.”

At Pennsylvania’s Gettysburg College, Roizman “studied physics and math strictly because I was good analytically. I thought I could be a math teacher, a physicist or even an engineer. I interviewed with various firms that came to look at my graduating class and they basically said, ‘You can start at $5,000 a year and work up to $7,500.’ I thought, ‘Wow, this is something I really don’t even want to do and I’ll probably end up being poor.’ I then asked my father how much I could make as a camera assistant and he said, ‘If you’re lucky, you’re good, and you work a lot, you can make about $10,000 and work up to more.’”

Despite a lack of creative interest in cinematography, Roizman had hands-on camera experience, having worked “during the summers for an equipment rental company in New York. The owner did my dad a favor by giving me a job. I worked in the camera room and learned how to set them up, take them apart and thread them. There I learned what an assistant did and got to know the equipment pretty well. Becoming an assistant sounded like a better opportunity — and at least a little looser. I was definitely not a 9-to-5 type. But my father was against the idea.”

Sol Roizman was what his son would describe “as a moderately successful cameraman. But I could sense the pressure he was going through at the time after losing his job. He suddenly had to freelance because newsreels were defunct after the onset of television. He was worried for me and didn’t want me go into this difficult business.”

Fortunately, Sol Roizman was able to help his son, including getting him into the camera union. “He got me in while I was still in college, just as a fail safe,” the cinematographer said with a smile. “He got me freelance work on commercials. Then I got a lot of work assisting at MPO Videotronics, which was the largest commercial house in the business. Gerald Hirschfeld [ASC] was one of the owners of that company and a tough, very demanding, good cinematographer.”

However, Hirschfeld wasn’t convinced that Roizman had enough experience to be dependable, so “Gerry kicked me out of the company and forbid me to work there until I got more.”

A turning point for Roizman came soon after, as he apprenticed with “a cameraman named Arkos Farkus, a Hungarian who was a good friend of my father’s and a wonderful guy. He took me under his wing as his assistant. I was determined to learn the craft and be the best at what I did. I was a sponge, and I soaked up everything I could.”

At the end of that year, Hirschfeld needed a new camera assistant, and brought Owen back on a trial basis — soon earning a position as Hirschfeld’s staff assistant and “a nice steady income.” With the elder Roizman frequently working as Hirschfeld’s operator, the connection between the father and son grew. “It’s hard to define the relationship my father and I had,” Roizman said. “He was very supportive throughout my athletic period, but he was afraid for me when I came into the film business because I was a reflection on him — if I failed, he failed. But if I made it, he could be proud of me. He was happy that I was earning a living, and we were starting to grow together as well, partially because we could talk about the business and I could pick his brain.

“Father-son relationships, at a certain time in life, are difficult — then all of a sudden they become great,” Roizman said. “Usually this is because of the child maturing, but also the father accepting.”

Assisting Hirschfeld on the 1964 feature Fail Safe, directed by Sidney Lumet, was another step in Roizman’s career evolution. “This was a major Hollywood feature and I was nervous as hell. Here was Henry Fonda and Lumet, who works like a house on fire. Gerry was taking a chance by using me, but he had confidence in me even though I didn’t. So it was a great experience.”

“When I became an operator, and by that time cinematography had become my primary interest in life, that’s when I started to appreciate how difficult the craft was, and what to look for: movement, light, composition and, of course, performances.”

Meanwhile, Roizman’s family was struck by tragedy as his brother died in a car accident. “It destroyed my father,” he said. “He died of a heart attack just three months later and it was very tough for all of us because it was really a time when we were growing together.”

Future ASC member Gordon Willis became Hirschfeld’s new operator at MPO. “We worked as a team for about a year,” Roizman said. “Then Gordy wanted to sow his oats and go shoot.”

With Willis gone, Hirschfeld needed a new operator. “But he was a tough guy to work for and nobody he tried out could cut Roizman recalled. “Finally, I said, ‘Gerry, why don’t you give me a chance?’” After a trial period, he got the job, with friend Enrique “Ricky” Bravo assisting.

Asked at what point he began to consider his work in cinematography as more than a job, Roizman thoughtfully replied, “I decided early on that I didn’t want to carry camera cases all over the place, but my ambition grew slowly. I had no idea — none — that I would go where I actually did. I never once thought about becoming a ‘great cinematographer.’ But when I became an operator, that’s when the ambition started. I realized that I could shoot, that I liked what I was doing, and that I could be good at it.”

“I wouldn’t trade my training for anything. When I set up a shot, I know what it takes to make that shot. I could pull the focus on that shot, I could operate that shot, and I can light it.”

At that point in time, a change in the way commercials were being shot finally sparked Roizman’s creative interest in his craft. “Still photographers were starting to influence how we were lighting — moving us toward single-source, soft lighting. The established cinematographers were working from old techniques — just nice, clean stuff for TV. But these young ad company people wanted to change that. And I was their age and I loved it. So when I got my first breaks to shoot things, that’s the way I did it. And my interest in lighting and cinematography grew out of that.”

This growing passion was a feeling Roizman was well-aquatinted with. “Any time I have gone into anything I have had this competitive nature of being the best,” he said. “When I played baseball, I watched all the games and I knew all the players and their batting averages. I was totally focused on that and had no time for anything else. When I became an operator, and by that time cinematography had become my primary interest in life, that’s when I started to appreciate how difficult the craft was, and what to look for: movement, light, composition and, of course, performances.

Asked to appraise his learning experience as an assistant and then operator, Roizman compared it to the film school background that many cinematographers how have today, saying, “You can come out of film school having done a little assistant work, some operating, gaffing, and a little bit of everything and go out and get some experience doing music videos and commercials. They learn more about the art part of the craft at a younger age, whereas when you go through the crew system as I did, you learn about the mechanical parts first and then slowly move into the art.

“But I wouldn’t trade my training for anything. When I set up a shot, I know what it takes to make that shot. I could pull the focus on that shot, I could operate that shot, and I can light it. However, knowing that can also sometimes be a hindrance to your creativity because you might think, ‘Maybe we shouldn’t do it this way because I know how tough it’s going to be.’ You might censor yourself. So there’s a Catch-22 dichotomy to both those backgrounds.

“What I didn’t get training in was editing, and I didn’t get to study other people’s work the way it can be done now. We had to go to the movies and sit through the whole thing just to see a particular shot. And if you blinked, you couldn’t run it back again. There was a lot more trial and error. But [at that time] I never went to the movies to study other people’s work, although there were definitely films that left an impression on me, like In Cold Blood [1966, shot by Conrad L. Hall, ASC]. That blew me away. I was shooting by then, and as a cinematographer, I could recognize that it was a great piece of visual work.”

As 1970 began, Roizman was hoping to shoot his first feature, and narrowly lost the director of photography position on the experimental film End of the Road (1970) to friend Gordon Willis. “I was disappointed that I didn’t get that picture. When I saw how Gordon’s career was starting to flourish, all I could think was, ‘God, what can I do to get off the ground here?’”

Roizman’s first break came on “an extremely low-budget picture” entitled Stop!, directed by pioneering Black filmmaker Bill Gunn and shot on location in Puerto Rico. The cinematographer recalled, “Dick DiBona, who was the owner of General Camera Corporation of America, mentioned my name to the producer. They would get me cheap, naturally. I just wanted to do a picture. I went down to Puerto Rico and I approached it the way I did commercials. The director didn’t know anything about cinematography and just left everything up to me, so I had a field day and it looked really good, but the film was never released.”

Stop! was only the second major-studio production helmed by an African-American director, after Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree (1969). Standing in the way was the “X” rating the picture earned from the MPAA for its extensive nudity and frank sexuality. In the decades since, Stop! has screened a number of times as part of retrospectives on Gunn’s work, but never had a home video release. Warner Bros., which owns the title, has no current plans for it.

Following this disappointment, DiBona then heard that director William Friedkin was looking for someone to shoot a crime film entitled The French Connection and again recommended Roizman. “Dick had shown Friedkin my commercial reel and his attitude was, ‘Well what can he do with a feature?’” Roizman says. “He arranged a screening of Stop! But after we got through about four reels, Friedkin said, ‘I can’t take this picture anymore!’ and we went across the street to have a cup of coffee.

“Friedkin said, ‘Look, that stuff was beautiful, but the picture I want to shoot is gritty, dingy, and almost documentary in style. Can you do that?’ Of course, I wanted the job and was ready to say anything. So I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ He liked the attitude I had and offered me the job.”

Roizman had seen Friedkin’s previous pictures, The Boys in the Band and The Night They Raided Minski’s and was impressed with his directorial style, but what was more interesting to the cinematographer was the French Connectionscript by Ernest Tidyman, based on the novel by Robin Moore. “It was truly great,” he says, “And through the years, there have been only a handful of scripts that even came close to striking me like that one did.”

Even a cursory look at Roizman’s credits reveals an extremely high percentage of quality projects — in part the result of his selection of material. Asked to describe his tactics in selecting scripts and how that shapes his cinematographic approach, Roizman explained, “I’m very objective about just about anything I approach, including scripts. I look at a script and I say, ‘Okay, how can I make this film feel like it’s real, like it is happening? How can I transport them into the thick of the film without them realizing it?’

“I take this approach because I remember one of the things that impressed me as a filmgoer. I never thought of a camera being there, I never thought of lights — and whenever anything drew attention to the fact there was a light or a camera, it distracted me. I remember when I saw The Battle for Algiers and thought, ‘This is not a documentary. What an amazing job, because you just felt like you were there.’ That’s the way I wanted to shoot my pictures, so I looked for material that would take me in that direction.”

“The French Connection script dictated a certain realistic quality. When I read it, I pictured walking through New York in the middle of winter following somebody in the streets.”

However, there have been various reasons why Roizman has signed on to do the pictures he has done. He explains, “With my first picture, Stop!, I was ready to do anything. When French Connection came my way, I just happened to be the luckiest guy in the world because it was a brilliant script. I later shot The Gang Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight because they came to me while I was still shooting The French Connection and I said, ‘Wow, another job! I’ll do it’ On Play It Again, Sam I loved that script and I thought it would be great to work with Woody Allen. The Heartbreak Kid was the same way; it was a really good script. And then The Exorcist came and that was also great piece of work.

“The French Connection script dictated a certain realistic quality. When I read it, I pictured walking through New York in the middle of winter following somebody in the streets. I imagined the coolness in the air, the bleakness, the darkness, and the danger that lurks all over New York at night. Then I tried to develop a visual look based on that and said, ‘We’re shooting everything with available light.’ People would later ask if I really did shoot everything with available light and I would say, ‘Yeah, everything that was available on the truck.’

“At night, in the bars and streets, we used a lot of small fixtures in places that audiences weren’t aware of — photofloods and gimmick lights. Like on the streetlights, we would hang a light above the actual fixture to just amplify the existing lamp, so the source would look like it was coming from the same place. If we just shot with existing light, we wouldn’t have gotten an image. You could do it nowadays a little easier because we have faster films; we didn’t have fast films in those days. We were using 5254, which was 100 ASA, and I underexposed it, printed it up and did everything to get every inch I could out of the film.

“We used old Cooke and Baltar lenses that were f/2.3, whereas nowadays you get them down to an f/1 or 1.4. So we had to light. I have some stills from The French Connection where you can see lights hanging everywhere — you wouldn’t believe how many lights were there.”

But the film was also a “breath of fresh air” for Roizman, after decade of glossy commercial work: “We didn’t have any female stars in the picture, so the women could look real — like who they were supposed to be. And the men were not supposed to be glamorous in any way. None of those guys — Gene Hackman, Roy Scheider — ever had an ego about the way they looked. In fact, the uglier they looked the better it was for their characters. Besides being talented, Gene and Roy are two fabulous guys to work with. So I was able to light scenes strictly for the mood of what I thought it should be.”

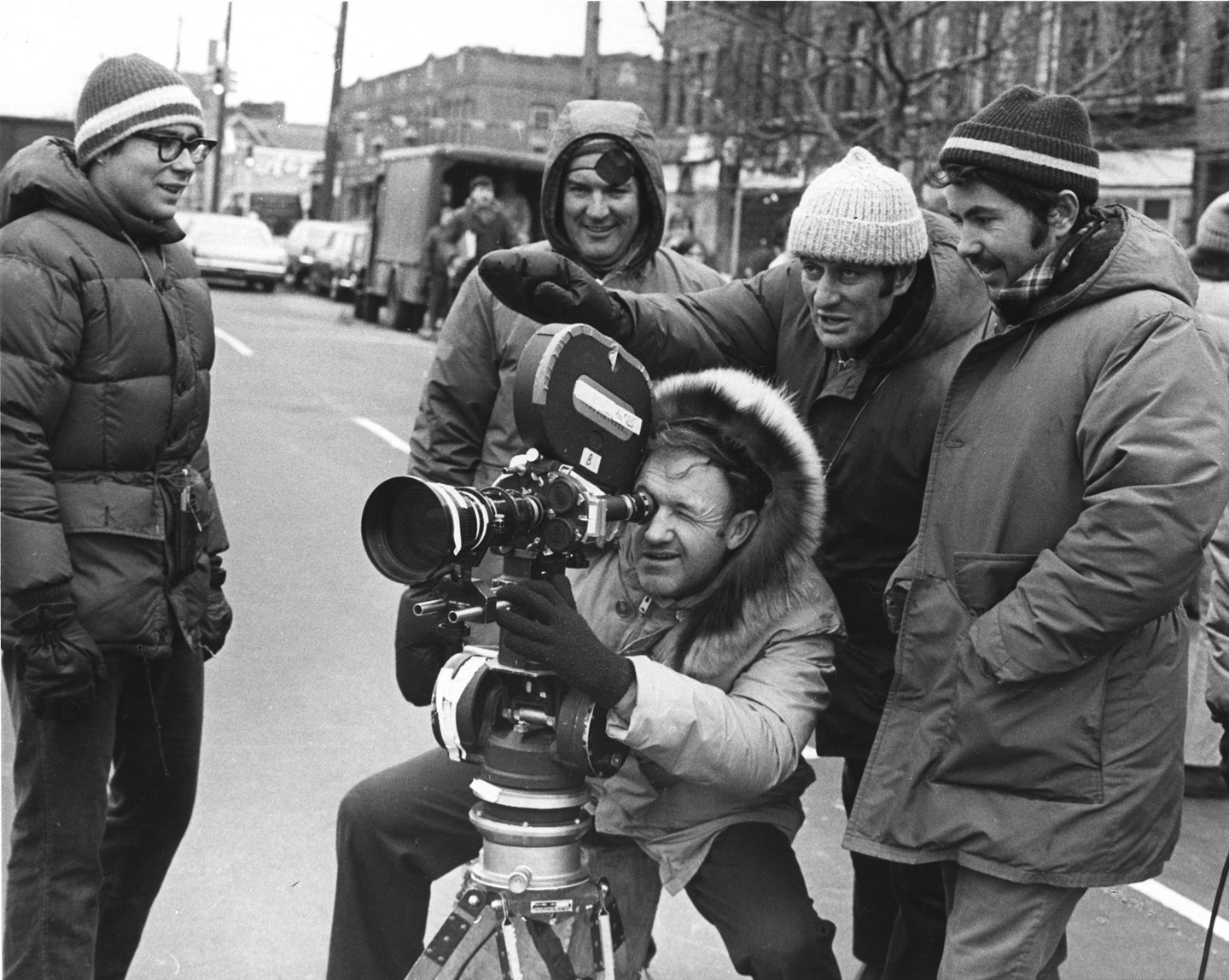

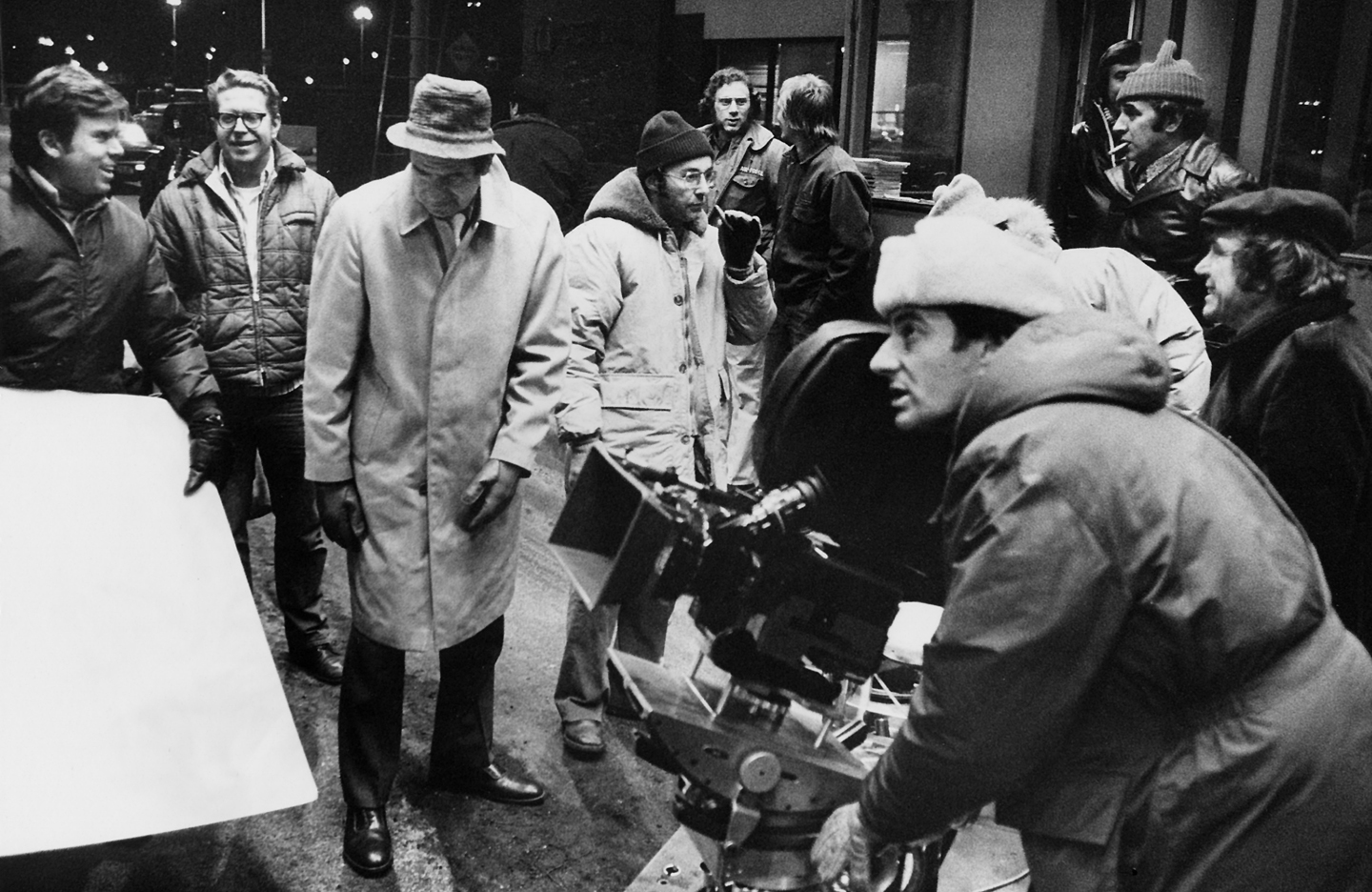

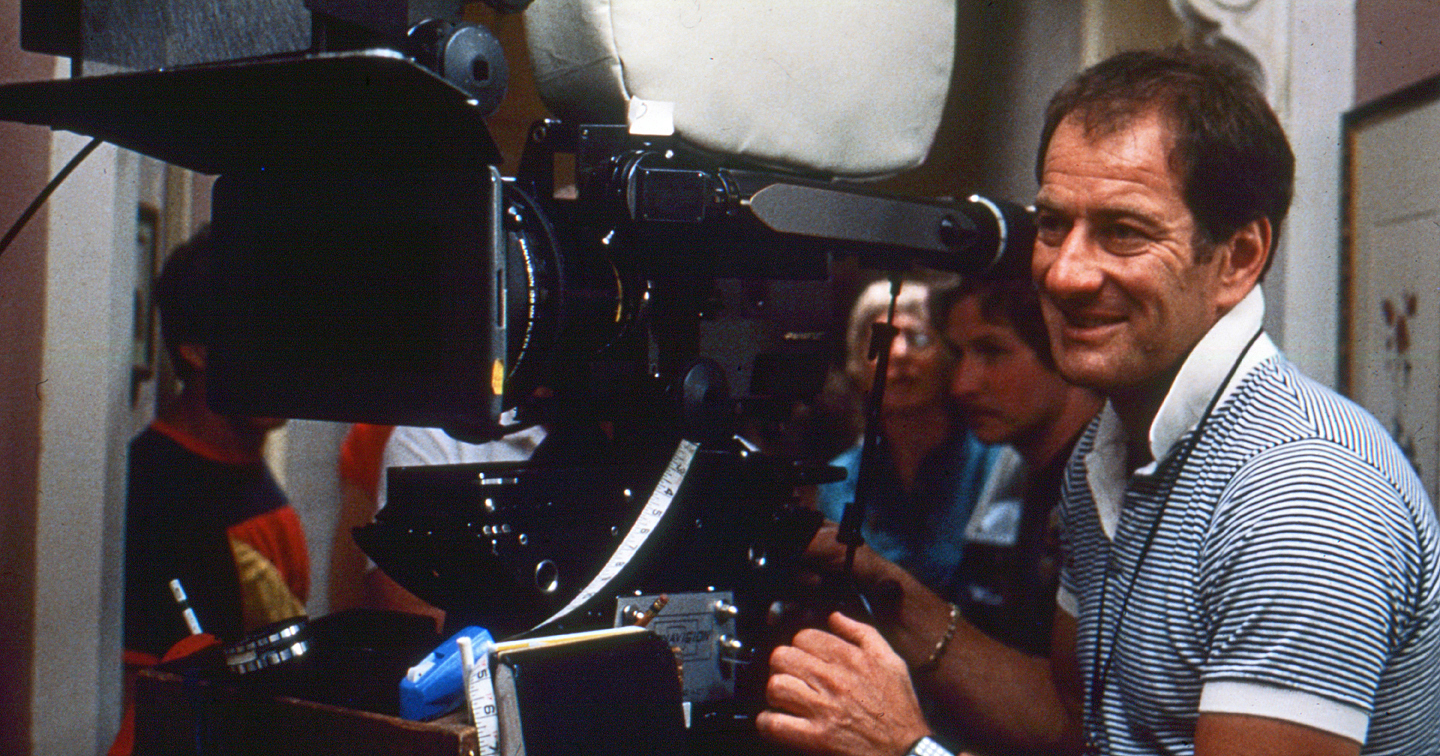

Filled with kinetic energy, the picture is also notable for its use of handheld camerawork. “We shot about 70 percent of it handheld, mostly with Arri IIBs” Roizman said. “Billy [Friedkin] wanted to have an uneasy feeling to the whole look of the picture and it was also a way to work fast. We would just grab the camera and shoot. Sometimes we’d use two cameras — I would take one, my operator, Enrique Bravo, would take the other and we’d just shoot.”

Despite his feelings of success upon finishing the film, Roizman still had little idea of what he had accomplished in terms of laying the foundation for a signature style that he would modify and refine throughout his career. In fact, he as of yet didn’t realize he had his own style: “Just before The French Connection came out, I went to see The Conformist, which Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] had shot. I remember sitting there in the theater with Mona, my wife, and seeing this film that was totally different stylistically from what I had just done. And the cinematography blew me away. At the end of the picture, I turned to my Mona and said, ‘I’ve got to get out of this business. I can’t do that kind of work.’

“Then The French Connection came out and was nominated for an Academy Award. I only realized then that that film was done in a style I had set for myself — ‘gritty New York street photography,’ which I was then labeled as doing. I had to totally change everything I’d ever learned in order to shoot The French Connection, but by the time I finished it, that was the way I was shooting and thinking about shooting in my mind. The Conformist helped me became aware of other styles and how beautiful cinematography can be if you are allowed to go in your own direction.”

Roizman still enjoys the irony of using his knowledge of polished commercial techniques to make such a “realistic” film. He smiles, saying, “I always thought that was pretty funny. So be it — I wasn’t going to tell them the truth.”

After completing The French Connection, Roizman dove directly into a trio of comedies, including director Herbert Ross’ Play It Again, Sam, based on the play by Woody Allen. In this film, the cinematographer conformed his approach to the material, resulting in a much more theatrical effect than in most of his other pictures. The lighting itself is often instilled with humor, particularly as the character Allan Felix, a daydreamer movie critic played by Allen, is visited by the spirit of Humphrey Bogart — who offers advice on dealing with “dames.” Said the cinematographer, “There are a lot of fantasy situations in that film, and rather than being cliché and putting diffusion on the lens or flaring things out, I tried to suggest that with a change of lighting. In the film’s real-world situations, I tried to keep the lighting as realistic and natural as possible. Then, whenever Bogart appeared, I tried to give it that mysterious, dramatic, Casablanca quality.”

Indeed, as the spectral Bogart is magically illuminated in a film noir toplight, appearing almost monochromatic in otherwise color-filled settings. “I lit the actor playing Bogart, Jerry Lacy, in such a way that he had an atmosphere to go with the persona,” Roizman said. “And I tried to accent his facial features in such a way that you couldn’t quite see that it wasn’t Bogart, but you got the impression that it might have been him.”

At the end of the film, Allen’s character finds himself assuming Bogart’s role in Casablanca to a T, saying farewell to the woman he loves at a fog-shrouded airport. Similarly, Roizman assumed cinematographer Arthur Edeson, ASC’s role in that 1942 classic. “But I never really recreated the look he had in Casablanca because I tried to do it with soft light,” Roizman said. “I was so into soft light at the time that I didn’t study the original scene enough to realize that it was all hard light and very carefully placed shadows. When I look back, I say, ‘I could have done it so much better than that!’

“I still love soft light because it’s the closest thing to natural light. All my commercial training had been with hard lighting. When I started shooting, soft lighting came into practice and that is what I was interested in. Actually, I probably got interested in it because it was easier to do.”

“Billy called me up and said, ‘I’ve got a great story for us to do, The Exorcist.’ He described the story — he’s a great storyteller — and described it in such a way that I said, ‘That sounds great!’”

Roizman resumed his collaboration with director William Friedkin on The Exorcist. The cinematographer’s initial encounter with the material came while shooting Play It Again, Sam on location in San Francisco. “I would come home after working long days,’ he recalled, “and Mona would be reading this book. I asked her what it was about and she said, ‘This young girl has been possessed by the devil and two priests are going to exorcise her.’ It sounded scary as hell and I had no desire to read it.

“After we finished Play It Again, Sam and came back East, Billy called me up and said, ‘I’ve got a great story for us to do, The Exorcist.’ He described the story — he’s a great storyteller — and described it in such a way that I said, ‘That sounds great!’ I told Mona about it and she said, ‘That’s the same story I told you about when we were in San Francisco!’ Billy did a good job of brainwashing me, so I read the book right away and loved it.

“I always like to research a picture as much as possible. I mean, if it’s comedy, there’s nothing to research. But on a picture like The Exorcist, it helped to know that there were actual cases like this and to experience the fright that I felt when I read about all these odd things.”

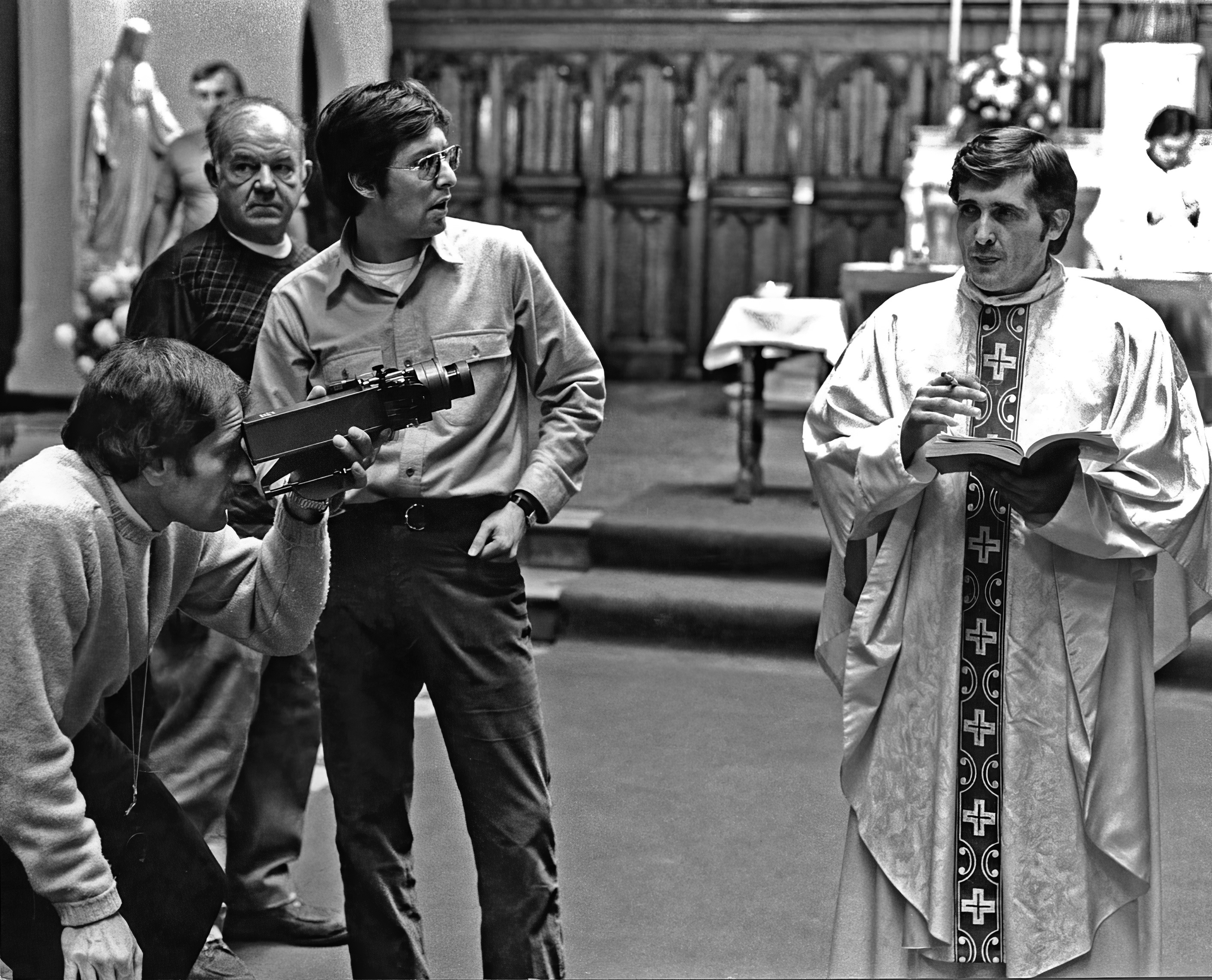

This connection to the real world played directly into Roizman’s style. “Billy didn’t want it to look like one of these old Hollywood horror films,” the cinematographer said. “He felt it would be best presented if the audience felt it had a realistic setting and that this story could actually happen. I agreed because if we could make the audience believe that there wasn’t any fancy lighting or funny stuff going on then they would really believe. So that’s what I went for.”

The Exorcist contains many indelible images, including the starkly sinister nighttime shot of Father Karas (Max Von Sydow) arriving to perform the exorcism. Standing outside the house with a dense fog swirling around him, a strange shaft of light falls upon his silhouetted figure. The light seems to emanate from nowhere, or perhaps the second-floor window of the possessed young girl’s bedroom. The mysterious, powerful image was selected as the film’s key art.

Roizman explained that the reveal, or introductory, shot for any character is of primary importance. “It’s sort of the signature shot, but, in my mind, no shot is unimportant,” he said. “And that’s where a director sometimes will have to hold me back — to keep me from taking too long to do something because I want to make every shot perfect. But we spent a lot of time on that shot in The Exorcist.

“Billy insisted that the shade on the bedroom window be pulled down. Well, if it’s an opaque shade, how are we going to get a shaft of light out of it? What we did was build a platform behind the window frame, on which we put an arc light. We then backed the shade away from the window about six feet and lit it separately. By putting the arc between the shade and the window frame, I could get a clean shaft of light that looked as if it was coming from the shade — although it was actually coming from between the shade and the frame.

“When we saw the dailies, there was the light — a 2K in the frame, before we brought it up on the dimmer. It’s right there. But nobody except us ever noticed it, and I never said a word about it. To this day, nobody’s ever said anything.”

The shaft didn’t quite hit Von Sydow, so I had another light put down in the street — it’s actually in the frame — and as he stepped into position, we brought it up on the dimmer. That created the aura, or halo, around him. When we did the rehearsal, during which time they shot the still used in the poster, it was foggy and you couldn’t see this second light until we dimmed it up. But by the time we did the take, the fog had blown out and you could see it.

“When we saw the dailies, there was the light — a 2K in the frame, before we brought it up on the dimmer. It’s right there. But nobody except us ever noticed it, and I never said a word about it. To this day, nobody’s ever said anything.”

Asked of his working relationship with Friedkin, which Roizman described as having been difficult for both men, the cinematographer explained, “There was a chemistry there for producing good work. I always felt like I contributed a tremendous amount to those two pictures. You’d have to interview every director I’ve worked with to find out what they think about me, but I have always thought of myself as a pain in the ass to a lot of them because I would get into their area. I’d make comments about the performances and suggestions about shots. A lot of directors want to make all those decision themselves, but my feeling is, ‘I’ll make the suggestion and they can take it or leave it.’

“Sometimes I’ll be persistent until they tell me to shut up or they take my advice. I used to whisper in Friedkin’s ear a lot, even at times when we didn’t get along. And he made major contributions to what I was doing — primarily by letting me do my work and encouraging me. On The Exorcist, the studio wanted to fire me — we were very over-schedule — and Billy said, ‘There’s no way I am going to let them fire you, I like your work too much.’ That was certainly an encouragement.”

Roizman enjoyed many successful collaborations with directors, which undoubtedly has been a factor in the consistent quality of his filmography. “The director-cinematographer relationship is somewhat akin to a marriage,” he said. “Some directors might not want me as a husband or a wife, but there is a lot of give and take. And there has to be a friendship to work with someone more than once. I have worked with Ulu Grosbard a couple of times — I love him, we get along great. Harold Becker and I did three pictures; he is one of my closest friends. Sydney Pollack and I have done five pictures together, and I have done four with Lawrence Kasdan.

“I consider them all to be nice people that I’d like to go to dinner with and talk film with and be around. But it is a marriage, and we have to work on it on a daily basis, just as you do with you spouse in the real would. Sometimes we’d have disagreements and have to work them out. Sidney and I sometimes disagreed about things, but it never went further than that particular moment. Larry Kasdan and I — and I love Larry — but we had some knock-down, drag-out arguments. But we were both fighting for the same cause — the picture.”

The director allowing the cinematographer creative room and means to practice their craft was of tremendous value to Roizman. “Later in my career, I had a new picture open one Friday and the next morning I got a call from a director I’d worked with a few times,” he remembered. “He was very complimentary and then said, ‘Your work is so different, so expressive — why don’t you shoot like that for me?’ I had to be honest, and said, ‘Because you don’t let me.’ And that’s the truth, because the cinematographer can only do what the director asks for.”

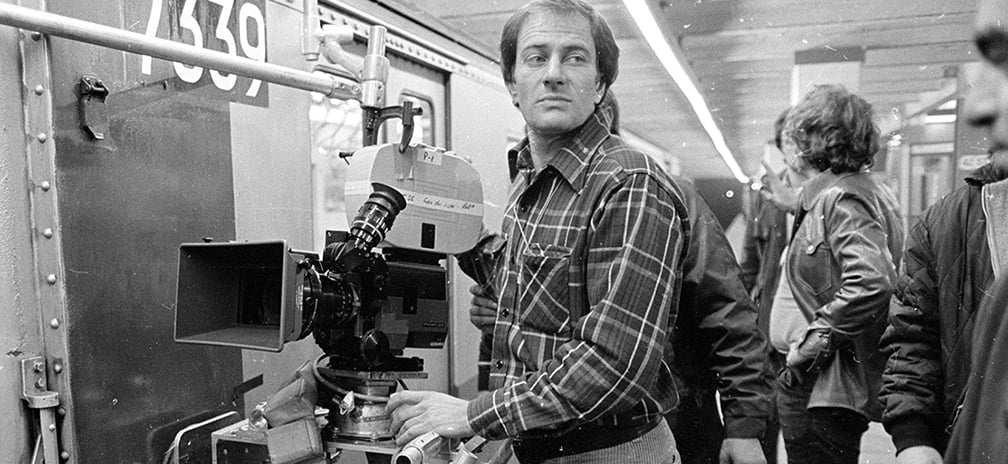

Roizman returned to his gritty “New York” style for The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, a heist film directed by Joe Sargent that featured the hijacking of a subway car. “Pelham had a realistic scariness to it,” he said, “and one of the ways to get that scariness was to create a mood that was real, like it could happen. So that is the approach that I took to doing it.”

The tunnels and cramped train interiors benefited from Roizman’s use of the anamorphic 2.39:1 format, but that compelled him to become even more inventive with his lighting, as the widescreen frame left little room for sources. “We used the existing florescents in the cars,” he recalled, “but when they went out, we switched over to ‘emergency lighting’ which consisted of these little incandescent bulbs. We built them right into the regular fixtures so you couldn’t see them while the fluorescents were on.

“People have asked how I lit the tunnels on Pelham. Basically, I basically changed out all of the bulbs in the tunnels to photofloods. With those, I had enough ambient light to get some exposure. Whenever I had a subject, we would just fill it in with the slightest bit of light, maybe 3 to 5 foot candles, so it looked real as hell.

“We pre-flashed the negative which gave me more detail in the shadows. I also force-developed it, as I did in The French Connection, but I didn’t underexpose it. I exposed it normally according to the forced-development. In The French Connection, I force-developed it and underexposed that so we had to print on very low print lights, which gave it kind of a grainy, muddy look. On Pelham, we got a richer quality. The anamorphic format alone would make it a little glossier.

“I learned a little bit between French Connection and Pelham about how to get a little slicker when I wanted to, but I still had the same theories: What is the situation? Where is the light coming from? How can I recreate that look?”

“I learned a little bit between French Connection and Pelham about how to get a little slicker when I wanted to, but I still had the same theories: What is the situation? Where is the light coming from? How can I recreate that look? I’m an amateur magician, and there’s nothing I like better than fooling somebody. So I always took that approach to my work. The biggest compliment I can get is somebody asking, ‘How did you do that?’ It’s like they’re watching a good magic trick.”

Asking questions of his peers and offering his own answers is another way Roizman bettered his craft: “There are plenty of people whose brains I have wanted to pick,” he said. “Connie Hall and I joked about the time when he was in New York shooting Marathon Man and I was about to go off and do Return of a Man Called Horse. I had never done a Western before and I wanted to pick his brain about doing day-for-night work So we went out for dinner and talked through the night. Even years later he has always teased me about it. In fact, after he saw Grand Canyon [AC Nov. 1991], Connie called me up and said, ‘You sure have come a long way since that night we had dinner.’

“Even today, there are people who I talk with after going to the movies — talking about technique. It’s a wonderful sharing that goes on sometimes, although with some people it doesn’t. Storaro would never talk about technique — he would talk about the art, the philosophy of art, and color. He would never say, ‘I used this particular light with this as a backlight.’

“You can ask somebody how they did something, but deep down it comes down to one word: Taste. I think those who have good taste in most people’s eyes are the ones who are successful. People who don’t have good taste? It doesn’t matter how much they know; they don’t have the taste to know when it’s right. There are some guys coming up now who I would love to watch work. I find it interesting to see what they do and I wonder how they got certain effects and what they do on set to achieve them. Those are kind of people I wouldn’t mind screening a picture with.”

Roizman was clearly on a successful creative roll in the mid-1970s, but he would still approach his work with care. “Until recently, I used to be petrified going into every picture,” the cinematographer candidly said. “I’d wonder if I would be able to get the kind of look I wanted, or if it would be good enough. Or if I would get my next job. I never had that burning confidence. I knew my stuff, but I felt like I was learning all the time. I would sit down and watch my films and I think, ‘If I could shoot this picture with what I know now, I could do it so much better.’

“At the time I did Three Days of the Condor, I had no idea if I did a good job or not. It wasn’t until the picture came out and people said, ‘That was great work you did on that picture’ that I knew — and to this day people think that is one of my best pieces. But I’ll look at and find all kinds of flaws. I also look at Condor and wonder how some things came out so well. So my career has been a constant internal re-evaluation.”

However, Roizman did feel his work was building upon itself in terms of his proficiency. “Network is a lot slicker-looking than The French Connection,” he said of his next project, the pitch-black satire directed by Sidney Lumet. “But, again, we were working with extremely low light levels. The reason on Network was that we shot most of the film in an actual Manhattan high-rise office building, in order to use the real skyline in the background instead of Translights. We were often shooting at night, through tinted windows, out on buildings that were not lit. I had to balance the light in the room to be able to also expose for those backgrounds. And in order to do that, I had to use very low light levels — often with 25-watt bulbs as key lights — and work wide open with fast lenses to get the exposure we needed.”

Even while dealing with such a seemingly hostile location, Roizman said that he works “mostly on instinct. It’s very hard for me sometimes to project how I think a scene should be lit before I see it rehearsed and staged. I try to think on my feet and just react to the moment. I have always thought of myself as a mood maker. I try to feel the mood of a scene, of a set, of a film and try to create that mood on film. I like to subconsciously transport the audience into the film so that they feel a scene as I think it should be portrayed visually.

“A lot of that comes from confidence and experience. Working years later as a commercial director, I had to had to have shot lists and think out the way I was going to do something well in advance. So on features, even though it’s the director’s job, I usually make up my own shot list of how I think a scene should be covered. Even in advance, especially if we have had time to rehearse the scene the day before or we are in the middle of something, I will make a shot list.

“This is also a way for me to communicate to my crew, but it’s still just a guideline because I might change what I had preconceived by reacting to the moment of a scene. Yet I always tried to start somewhere, because it made me think about the scene and visualize it as not just as a piece of writing but as a piece of filmmaking.

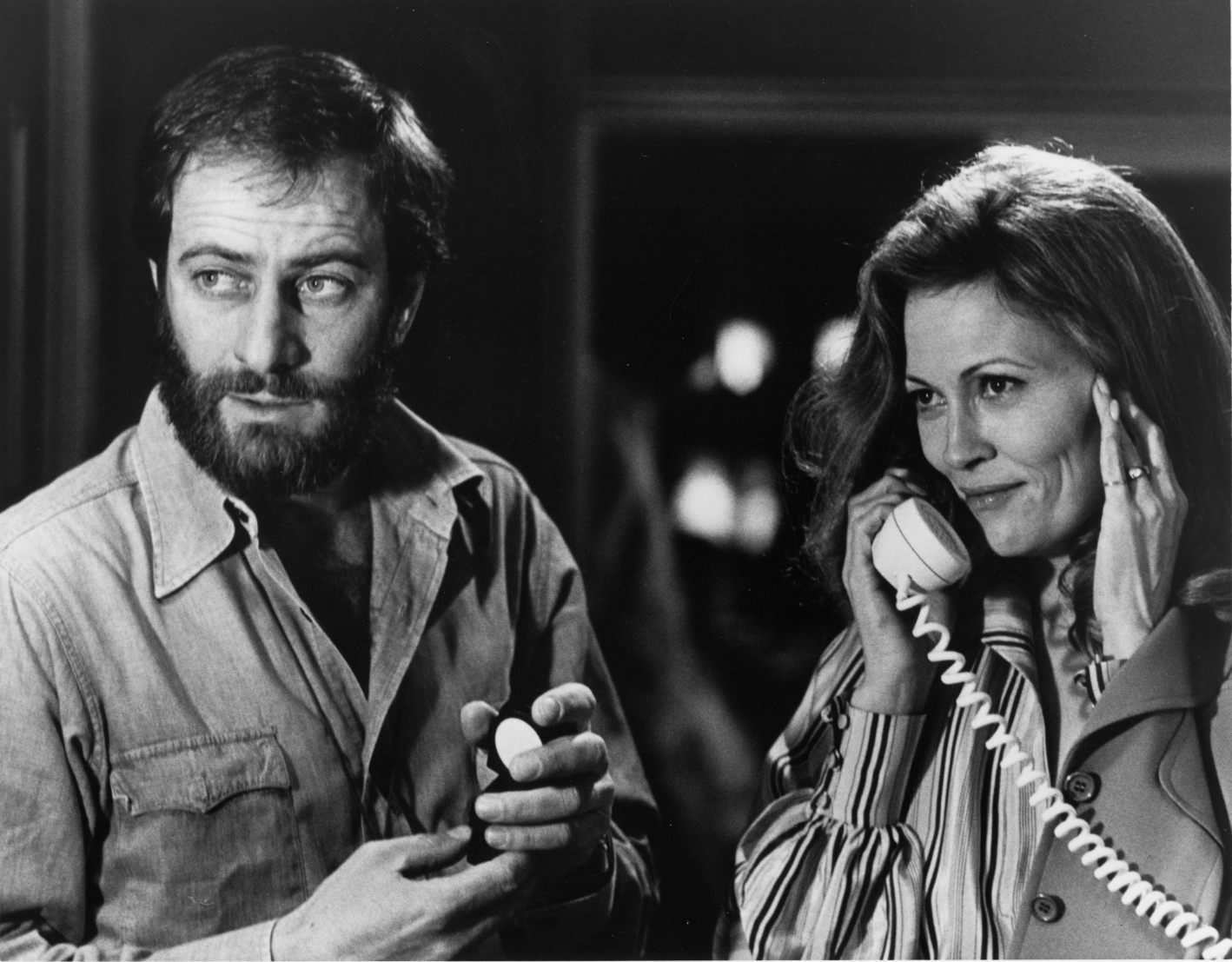

“With due respect to every other director I’ve worked with, Sydney Pollack is probably more knowledgeable about how he wants to shoot something than most others. I don’t mean how he wants to shoot it, but knowing what to do to get it. He’ll come up with things like that scene in Absence of Malice with Melinda Dillon waiting for the newspaper. I’m sure that must have been his idea to do that scene all in one shot. He is also probably the best editor of any director I have ever worked with. He likes to get in there and actually cut the film himself, so he knows what he needs for coverage and he covers a lot — much more than most people.”

A subsequent film Roizman did with Pollack is Tootsie (1982), the story of out-of-work actor Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) who become an overnight sensation in drag as an actress. Asked of his approach to comedy, Roizman said, “I may change my thinking as far as photography goes. You know, the old cliché that comedy is a little brighter? I tried not to think that way early on in my career, but the bottom line is that comedy is very different than drama.

“In drama you have to be more concerned about the face and the lines. In comedy, aside from the jokes, you have to be concerned with body language and sometimes facial expression to emphasize a joke. Those to me are more important than brightness or darkness. In my own personality, I have always thought of myself as having a pretty good sense of humor, I like to tease and keep a light atmosphere whenever I can.

“I would be inclined to think funnier while working on a comedy, but not necessarily, because basically it’s still a job to shoot something and to approach it in a professional manner. I have always thought of myself more as a visual recordist. I am there to see what’s happening and to record it on film in the best way possible. It’s not my humor or dramatic qualities that are going to enhance the story.”

While Roizman was proud of his work in the picture and honored to receive an Oscar nomination for his camerawork, he was also embarrassed by it: “This was the same year that Blade Runner was released and Jordan Cronenweth [ASC] wasn't even nominated. The fact is that Tootsie was a very successful film, and I just got swept up into the Oscar race.”

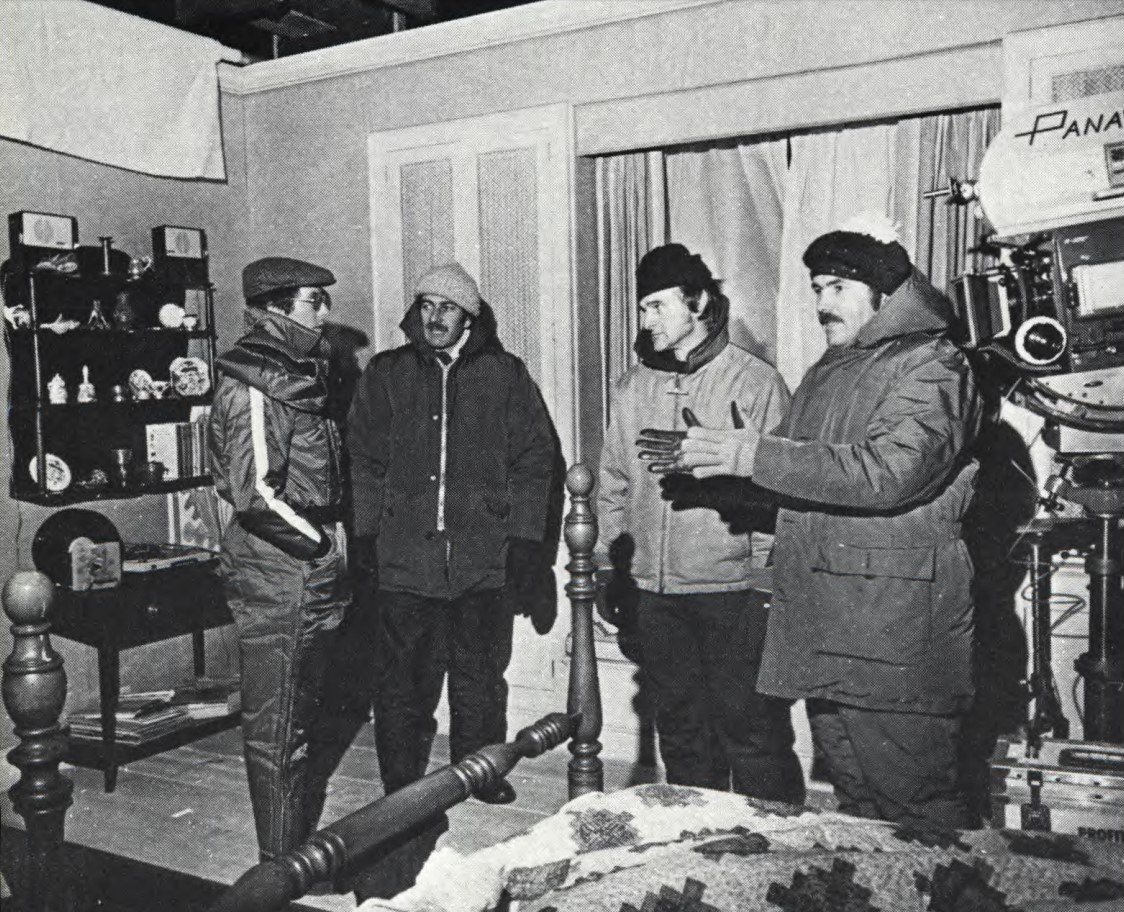

Despite what may seem to be hard-and-fast rules of methodology, Roizman’s experimentation has extended to his creative processes as well. For example, for the 1940’s-era mystery True Confessions, the cinematographer abandoned his usual research — a move inspired by director Ulu Grosbard. “I asked him if he saw the look of this film and he said, ‘As if it had been shot at that time,’” Roizman remembered. “‘I don’t want to use sepia, diffusion or anything else — but as if it was 1949 and we were shooting it.’ And that’s all.’

“I thought I’d desaturate the color a little in the final print. Like if you turned down the color intensity on your TV a little bit toward black-and-white, so you still had color but it was weak. I thought that would give it a quality almost like the film had faded over the years. So I didn’t use any diffusion, didn’t shoot any sepia, and didn’t use any special filters. I just shot it as though I was going to shoot it today, but the setting was 1949.

“I did ask Ulu to use [production designer] Steve Grimes, who did Condor. He said, ‘If you want him, that’s fine.’ Steve designed a great-looking period piece and all I had to do was capture it. I tried to shoot it realistically, but now it was different costumes, different decorations in the rooms, different cars, things like that. It was now 1949. I didn’t have to do anything else.

“When we went to do the final print, I went to find out about desaturating it and I showed Ulu the work print and he said, ‘I love it the way it is.’

“I liked it because the tones in the costumes were right. We had taken all the shirts and toned them way down, so they weren’t so white. That just softened everything. We had created a palette in the design of the film so that after I shot it we didn’t really have to do anything to it; it was all in the film. We didn’t preplan it that way, it just happened, and it worked.”

One of his final feature projects, Wyatt Earp (1994) offered Roizman not only the opportunity to work again with Kasdan but gave him the chance to indulge his penchant for shooting outdoors. “Shooting big exteriors is both fun and difficult,” he said, recalling the 113-day long Earp production, which primarily filmed near Santa Fe, New Mexico. “That was a really tough film to do, yet I can’t remember too many pictures where I had as good a time. The weather was brutal, but there was something about the chemistry of the people that made it fun to work on so I enjoyed the hell out of it.

“Before I did Wyatt Earp, I researched the Western style. I don’t know if I watched every Western that was ever made, but I sure saw a lot of them! But I wasn’t going to try to do it better than anything else, I was going to do it my own way. I just wanted to have references.”

Studying the work of others had often become a soul-searching experience for Roizman, who said, “So many times I’ve sat and looked at somebody else’s work and thought, ‘I don’t know if I could have done that. I’m not sure I know as much as people think I do.’ Then I’ll go teach a seminar or a class — I taught a graduate class at UCLA for a term, and I taught at the Maine Media Workshop — and realize how much I do know. Sometimes information gets put on the back burner of your brain and you don’t think about it. It gets stored up and you can call on it whenever you need to, but it’s only when you try to teach somebody else that you realize what you really know. And you realize what you don’t know, too.”

But few others had the doubts Roizman sometimes had about himself while trying to pursue excellence. In 1975, he was invited to join the American Society of Cinematographers, making him one of the organization’s youngest active members. Roizman — who was recommended for membership by Stanley Cortez, ASC — said, “When you see those letters after your name, they denote prestige. You obviously have to have some credentials to get in there, and that reflects on all the great cinematographers who have been members of the organization.

“I think the ASC represents a goal to aspiring cinematographers; someday they can be where we are, learn what we’ve learned and do what we have done.”

“I think the ASC represents a goal to aspiring cinematographers; someday they can be where we are, learn what we’ve learned and do what we have done. In my case, the ASC offered to me a sense of friendship and camaraderie amongst my peers that I don’t think I could have found anyplace else.”

Principally, this experience helped teach Roizman “that we are all different. And what one does, somebody may like and somebody else may not like, as in any art form. It took me a long time to settle into that idea and try not to be like somebody else, or to be as good or better than somebody else. But to just be myself and whatever it is it is.

“Vittorio Storaro, for instance, not only do I love his work, but I think he’s a great human being. But if he had shot The French Connection, it would have looked too pretty. He wouldn’t have gone as gritty as I did. So I was right for that job. And I doubt if I could have done what he did on just about all of his pictures

“I don’t think many guys would have shot The Godfather the way Gordon Willis did. He came up with a style and it had an incredibly individual look to it that people have tried to copy for years. If I had shot The Godfather, it would have looked different. So we all have our own way and taste of doing things.

“I feel that way about a lot of my fellow cinematographers. We are all individuals, and we all do things our own way; we don’t have to be better than the next, we just have to be ourselves. That’s the attitude I take; I just want to be myself. I’m going to make mistakes. I’m going to do things other people are not going to like. And if I have cinematographers say to me, ‘I love your work, you’re my hero,’ that makes me feel good, but that’s their taste.”

“When you’re nominated for an Oscar, you have to write a speech to thank all of the people that you want to thank in less than 60 seconds or less. But in this case, I got to get up and really thank all the people who helped me and stood by me throughout my career.”

The American Society of Cinematographers honored Roizman with its 1997 Lifetime Achievement Award. Fittingly, the honor came as a complete surprise to Roizman, though he was a vice-president and board member of the ASC and previously served as co-chair of the Awards Committee. “I got all choked up,” he said, recalling the moment he was told the news. “I called Mona to tell her and could hardly get the words out. It’s great feeling to be honored by your peers for the body of your work. I could sit and pick my work apart, but we’re not talking about a shot here or there, we are talking about the body of my work. So there must be enough good shots in there to make them think I’m worthy of this — which is nice to know.”

The ASC honor was presented by longtime friend Lawrence Kasdan, and comparing the experience to his five Academy Award nominations, Roizman said, “When you’re nominated for an Oscar, you have to write a speech to thank all of the people that you want to thank in less than 60 seconds or less. But in this case, I got to get up and really thank all the people who helped me and stood by me throughout my career. And I could take my time with it. Most people in the audience probably fell asleep, but it was thrilling to be able to genuinely and publicly do that.”

Following the production of the romantic comedy French Kiss (1995) — directed by Kasdan and largely shot in France — Roizman was forced into early retirement due to health issues stemming from his development of diabetes in the early 1970s and, later, post-polio syndrome. Which he described as “basically like getting polio all over again. It has been a gradual process, but I became unable to keep up with the hours you have to put in with this job. The combination caught up with me on Wyatt Earp, and I was fortunate to not only have a director and crew who could work with me, but an ASC colleague, John Bailey, who came in to take over for a while when I was unable to work. So my retirement was not by choice, but a necessity. And it has not been easy to accept. I feel that I still could have been working, and that that’s depressing, but I also look at what I’ve accomplished, and the talented people I’ve had the opportunity to work with, and I feel very blessed.”

An article about Roizman and his lighting style appears in the June 2023 issue of AC.