Arri’s Second Century

Founded by August Arnold and Robert Richter in 1917, the equipment manufacturer celebrates its 100th anniversary and looks ahead to new innovations.

Founded by August Arnold and Robert Richter, the equipment manufacturer celebrates its 100th anniversary and looks ahead to new innovations.

Images courtesy of Arri and also from the AC archives.

Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, ASC, AMC remembers cutting his teeth on a variety of Arri 16mm and 35mm film cameras as he came out of the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s film school. He shot his first five feature films with them, and eventually fell in love with the Arriflex 35 BL-4, calling it “my favorite camera for many years. It was the best camera in its moment, my main tool.”

With the Arriflex 235, Lubezki felt he had found “probably one of the best cameras ever made,” he says. “We were at a moment when film cameras were just amazing.”

Then, at the dawn of the new millennium, digital acquisition began its ascent. “Everything suddenly went to digital very fast,” Lubezki recalls. “That was a scary moment, because most people were complaining about the quality of digital images at the time. We had an amazing image quality one minute, and then we just lost it.”

ASC President Kees van Oostrum, another cinematographer who started using Arri film cameras to launch his career, remembers that time as well. He recalls the period of transition occurring “with a bang, within months.”

By then, however, Arri was well into development on an alternative that eventually helped the company not only survive the transition, but flourish. That alternative came to be known as the Alexa digital camera system.

As the venerable Munich, Germany-based company (now known as the Arri Group) turns 100 years old this year, it’s instructive to examine how the organization managed to position itself at the forefront of the digital-cinematography revolution during the period van Oostrum calls “the changeover.” As he notes, “You can get around a corner with any car, but the one that does it in the most expedient way — that, of course, becomes the preferred vehicle. In a nutshell, that’s what Arri did [with Alexa].”

Lubezki suggests that much of his award-winning work would have been fundamentally different had Arri not produced the Alexa system. “What people do not always realize is that the language of film is intrinsically connected to the tools we use to make the movies,” Lubezki notes. “We could not have done Gravity or Birdman without [Alexa].” Those two features (see AC Nov. ’13 and Dec. ’14, respectively) earned him the first two of three consecutive Academy Awards — all of which were for movies shot using various versions of the Alexa camera. The third film in Lubezki’s unprecedented Oscar run was 2015’s The Revenant, portions of which were shot with Arri’s Alexa 65 (AC Jan. ’16).

With the arrival of the Alexa, combined with other important achievements since the beginning of the digital era, “the last 10 years have seen the most decisive changes in the history of this company,” says ASC associate member Jörg Pohlman, who serves as co-managing director of the Arri Group along with fellow ASC associate Franz Kraus. And although these events are the most recent, some details of how the changes came about are not as widely understood as the milestones that occurred during the company’s first 90 years (see AC June ’08).

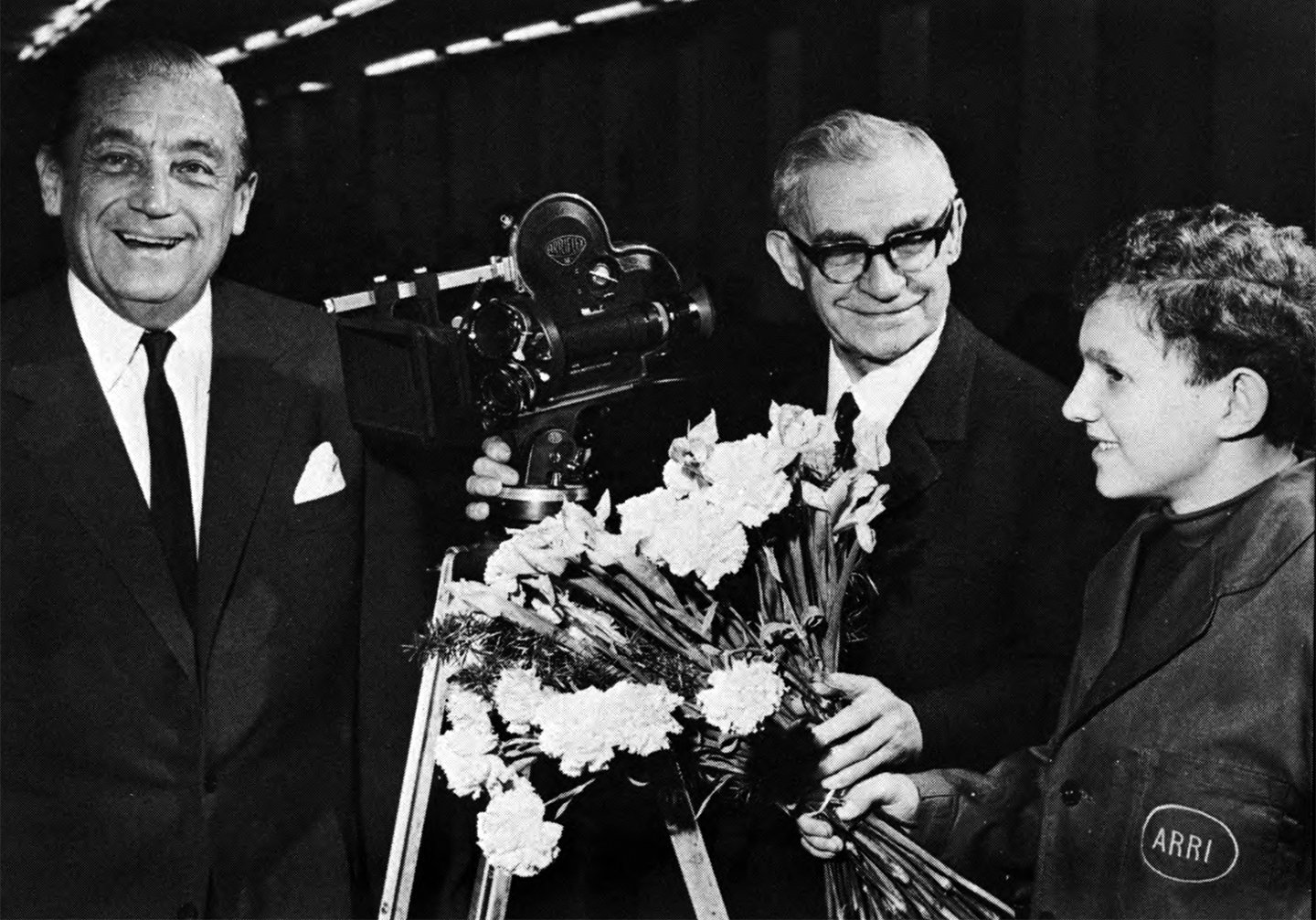

But one thing hasn’t changed in 100 years, company officials note, and that’s the agenda initiated by Arri founders and honorary ASC members August Arnold and Robert Richter: Determine what filmmakers need, then build tools to meet those needs. Indeed, to this day, Arri is a third-generation, family-run business — owned by Germany’s Richter/Stahl family, descendants of Robert Richter, as a privately held company.

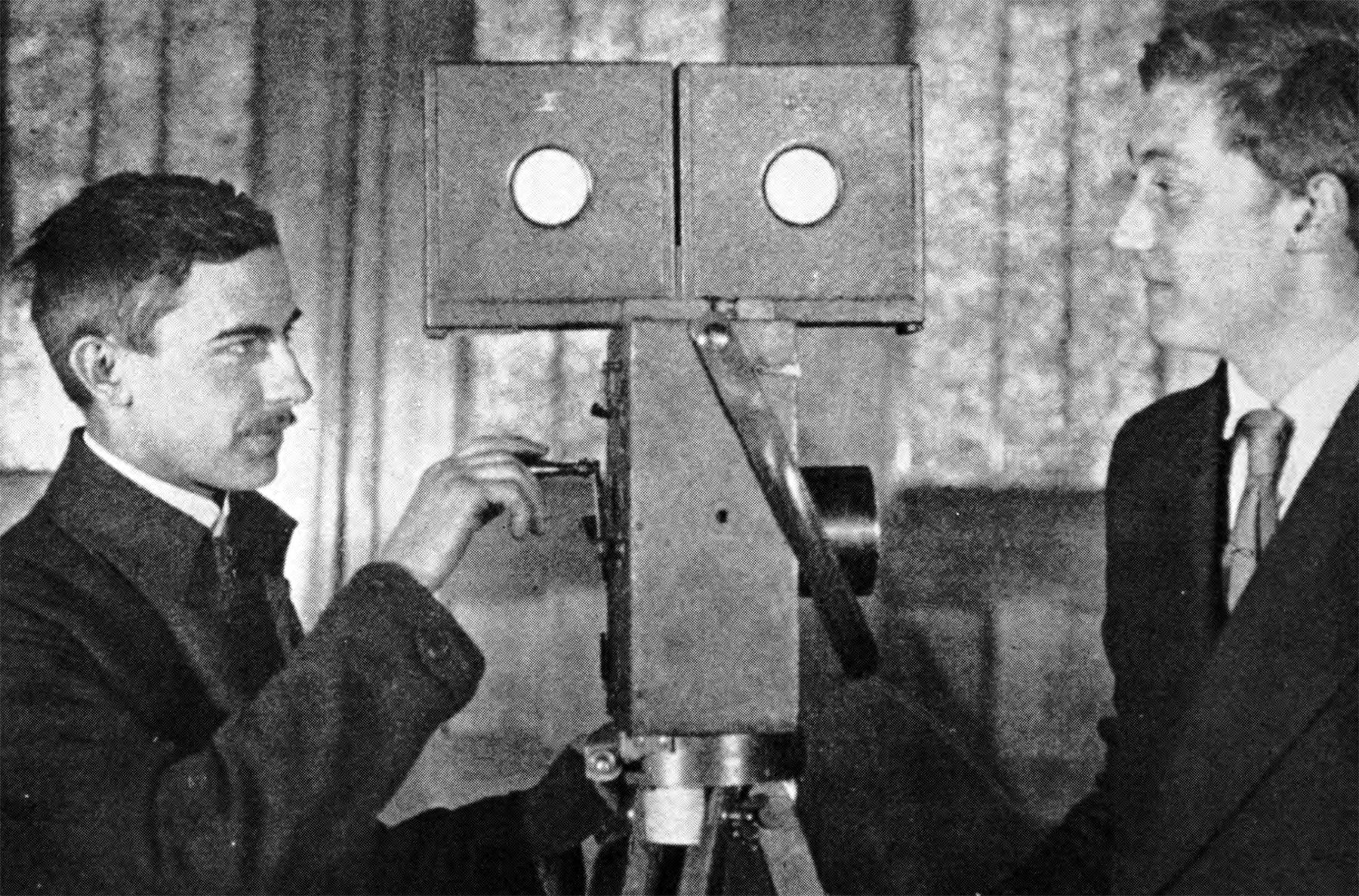

Arnold and Richter were themselves successful filmmakers in Germany when they launched the company, which started with an early motion-picture film printer built in 1917. The original Kinarri 35 film camera followed in 1924, and soon they were opening a film lab and servicing European and American filmmakers and studios.

The nascent company made lighting equipment, rapidly added lenses and mobile generators, and eventually debuted the first Arriflex camera — the Arriflex 35 — in 1936. It was a huge breakthrough as the first motion-picture camera to feature through-the-lens reflex viewing during operation.

Dozens of innovations followed. As the former president and CEO of Arri’s U.S. subsidiary, Volker Bahnemann, points out, the numerous AMPAS Sci-Tech-honored tools that flowed out of Arri between the early 1980s and the dawn of the 2000s alone, before the full digital transition had occurred — a list that includes Arriflex cameras and Arri/Zeiss lenses — were hugely impactful on the film industry.

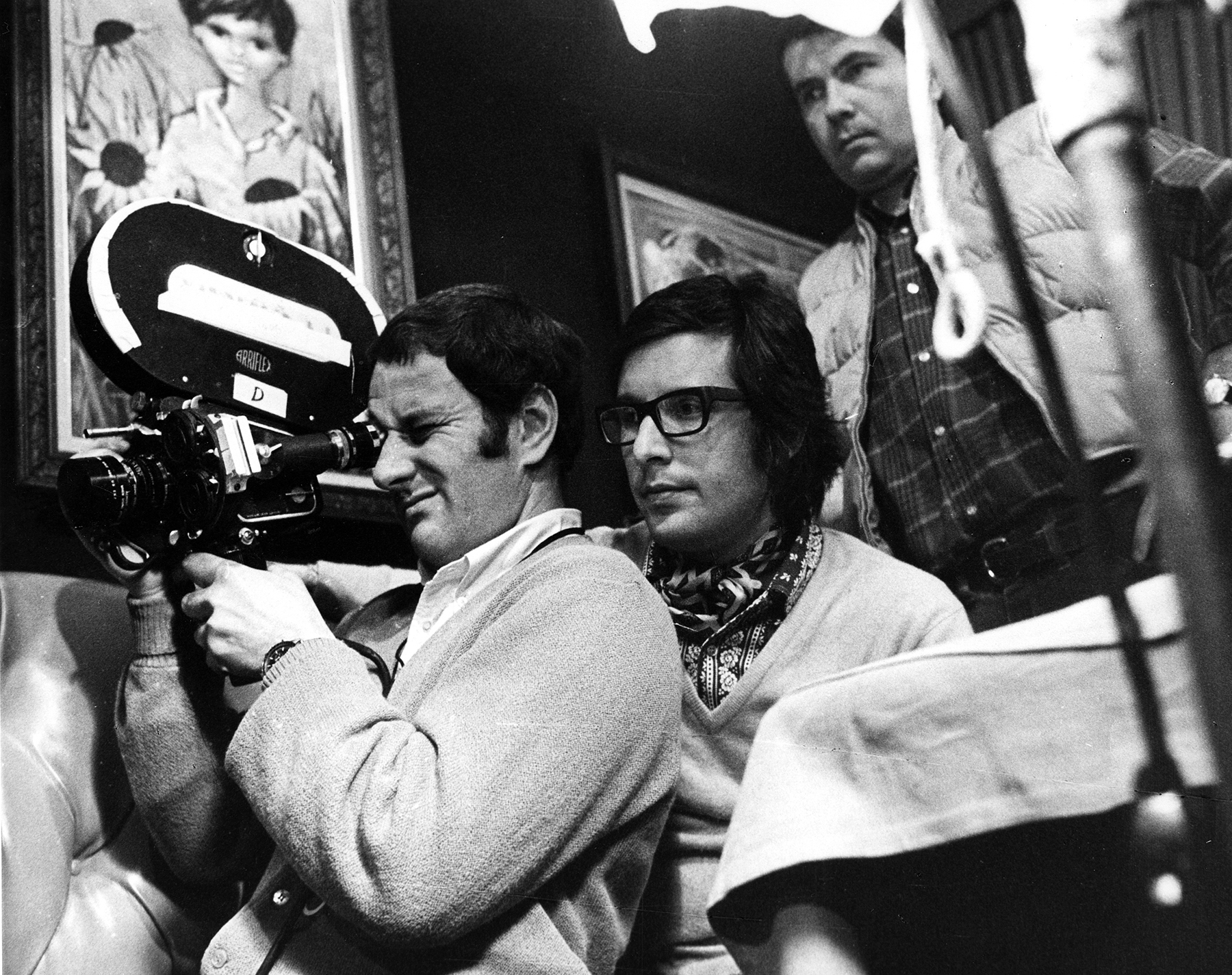

Arri’s film cameras also played a role in launching the careers and even changing the creative trajectories of dozens of well-known cinematographers. Ellen Kuras, ASC fondly recalls discovering the Arriflex SRII in 1987 when looking for a way to shoot the first short documentary on which she earned a cinematographer credit — the Student Academy Award-winning Samsara: Death and Rebirth in Cambodia, directed by Ellen Bruno.

“One of the prerequisites for doing that project was for me to bring my own camera,” Kuras says. “I couldn’t afford to rent a camera for three weeks, so I set out to buy one. Much to my luck, I was introduced to an equipment broker who was selling a complete SRII package only used twice. I loved using that camera, because not only was it quiet, but the magazines were really easy to load and the camera was extremely reliable. The SRII eventually became an essential extension of myself, accompanying me from doing documentaries to [shooting] narrative feature films.” This latter transition occurred when Kuras was asked to shoot Tom Kalin’s black-and-white feature Swoon, for which she recieved the Best Dramatic Cinematography Award at the 1992 Sundance Film Festival — her first of three.

Kuras shot several subsequent features with various Arri cameras, including Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (AC April ’04) and her 2008 Academy Award-nominated documentary The Betrayal – Nerakhoon, which she directed and shot (AC April ’08). “I shot that movie over the course of 20 years using my original SRII. When I finally sold that camera in the late 1990s, I went back and finished the film with a rented Arri SRIII.”

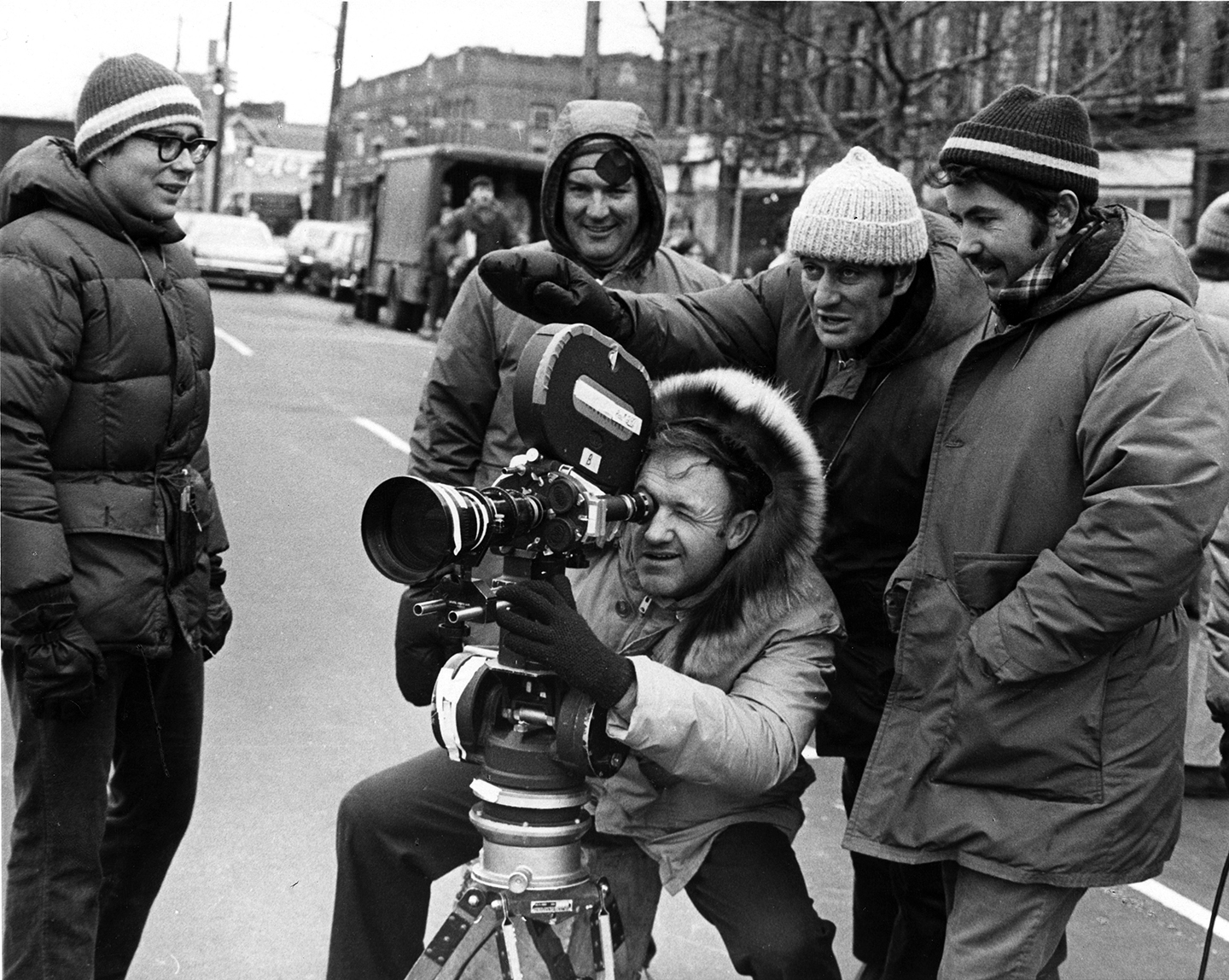

Owen Roizman, ASC recalls opting for an Arriflex IIC camera to shoot most of The French Connection, a project that earned him the first of his five Academy Award nominations. He says that camera “was a natural choice, since we knew we would be doing lots of handheld work on that movie, and the Arriflex camera was great for using a wide lens handheld. I loved that camera — it was one of the best cameras ever made. I could lift it up, hold it, put it against my chest, and walk around with it. It just fit naturally, and it was really easy to use handheld with a 200-foot or 400-foot magazine on it.”

For the film’s famous chase sequence, Roizman recounts, “We had three cameras mounted on the car — and then when we were out of the car, shooting toward it, we used the Arriflex on tripods and dollies, and whatever else I could get my hands on. We shot usually 20 or 21 frames [per second] to take the edge off the normal speed, to make it seem that things were going just a little bit faster.”

Such anecdotes from veteran cinematographers about Arri’s classic film cameras abound. Although the company stopped manufacturing Arriflex film cameras in 2010, it continues to service them across the industry for projects that opt for film acquisition.

As digital cameras emerged as a dominant force, a strategic plan was already in development at Arri’s longtime Munich headquarters to pursue digital-imaging technology. Indeed, Bahnemann remembers introducing his successor, fellow ASC associate member Glenn Kennel, on Bahnemann’s last day at Arri’s helm, at a presentation at the Directors Guild Theater in Los Angeles — and, as his last formal duty, presenting the Alexa camera to the industry.

Work to make that moment possible began when Arri decided to enter the digital film-recorder business, leading to the development of the Arrilaser. Kraus notes, “We worked closely on the film recorder with a [contract research organization] called the Fraunhofer IPM, in Freiburg, Germany. They had already [designed] a high-quality laser-based film printer for poster-size still pictures. We knew they understood the quality of imagery, but we needed it to be scaled to the small format, and to be enhanced in speed. And we did not want to use gas lasers; we wanted to use solid-state lasers. Eventually, the effort paid off.”

A sister product, the Arriscan, soon followed. As Kraus explains, that technology was developed in-house at Arri, which employed a monochrome version of the Alev CMOS imaging sensor developed for Arri by FillFactory — now part of On Semiconductor. After some work, the company was able to employ that sensor to emulate the look of film. “The development of world-class film recorders and scanners paved the way for the widespread adoption of the digital-intermediate process by the mid-2000 decade,” Kennel says. “More importantly, it provided the foundation for the development of Arri’s digital-camera and software expertise, supported Arri’s transition from a precision mechanical technology base to today’s base in digital electronics and software, and helped us build the technology foundation and hire the staff we needed to become a world-class digital-camera manufacturer.”

Kraus further notes that the objective of a digital camera was well understood within the company by the time those products took off. “At the time that we developed the Arriscan — I remember it very well — we all said it would be the first step to a digital camera,” he recalls. “But the one thing we couldn’t compromise on was that it would have to be as good as the capture of film was. We wanted to replicate film in its full perfection.”

Thus, a process that would end up taking approximately 10 years got underway, leading to the Alexa’s eventual 2009 debut. Kraus recalls the company’s decision not to rush the pursuit of achieving that film-like aesthetic. “We had built up our competence with [digital post] systems,” Kraus explains. “But it was a vague decision to move forward until a European Union-funded research project helped us design the Arriflex D-20.” That was the company’s first film-style digital camera, introduced in 2005, which incorporated 35mm CMOS sensor technology adapted from the Arriscan.

Bahnemann emphasizes that at the time the focus was squarely on making the D-20 the basis for Arri’s digital-camera development program moving forward. “We specifically referred to the D-20 as a ‘technology platform’ — not a product and not for sale,” he explains. “The D-21 was the next level of that, but it still was not intended as a sales product. Both the D-20 and D-21 were kept in our rental environment as image-test platforms. Of course, pressure from inside, as well as from the market, was very strong, but our technical management under the leadership of Franz Kraus resisted, insisting on sensor-imaging dynamic range close to film before building a camera around it.”

Bahnemann thus notes that there was no single “key moment” when Arri suddenly jumped into the digital-acquisition business. Rather, he says, “it was long, deliberate and patient work before we could confidently design and build the Alexa camera.”

Kraus and his team continued to push the digital-camera initiative, despite concerns about whether a company of Arri’s pedigree could make the digital transition without turning over virtually its entire mechanical-engineering staff. “But then 2009 came and the financial crisis hit the market, along with [people shooting 3D],” Kraus explains. “That was a time when we suddenly stopped selling film cameras. Younger members of the staff had already been asking for retraining, to be prepared for when our digital camera came. They felt that they could build digital cameras, because precision mechanics of a sort still applied. After all, everything in front of the sensor needed very high precision. So that terrible year, 2009, was a big motivator for us to change things. I’m proud that Arri could make that transition and keep the core workforce that we had, retrain them, and make high-quality digital products.”

According to ASC associate member Stephan Ukas-Bradley, Arri’s director of strategic business development and technical marketing, the company’s work with the D-20 and D-21 yielded experience, input and feedback that were essential to realizing the Alexa — a camera that would feature the next generation of sensor technology, based on Alev architecture. Ukas-Bradley relates, “Deploying the D-20 in a controlled manner through our own rentals and a selected group of rental partners enabled us to make sure the systems were properly maintained and gradually improved and updated, while [we learned] a tremendous amount about how a digital motion-picture camera has to perform in regard to image quality and robustness in the field. The next generation of the sensor technology became the basis of Alexa, with increased dynamic range, higher base sensitivity, and better signal-to-noise ratio than its predecessor. Product manager Marc Shipman-Mueller and a team of talented, motivated and very passionate engineers — headed by Achim Oehler, who had just finished the R&D of the Arriscan — then designed the camera essentially around the sensor.

“Nobody could have predicted the success of Alexa, but we did end up with lightning in a bottle for numerous reasons,” Ukas-Bradley adds. That lightning, he says, arrived precisely when “the industry was looking for a solid, file-based workflow solution, which we were fortunate to offer in raw, and also with our integrated and native ProRes recording.”

The result clearly impressed many of the industry’s most influential cinematographers. Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC was among them. He grew up in Munich, watching movies at Arri’s cinema, and became a user of Arriflex film cameras from the start of his career. He recalls that he was “skeptical at first, having to change my working methodology,” when he opted to use the Alexa system on a major feature: Judd Apatow’s 2012 comedy This Is 40.

“But it made sense,” Papamichael says, “since Judd liked doing very long takes — up to 30 minutes — and improvising with the actors. I quickly found a way to take advantage of Alexa’s low-light qualities and natural color representation. Later, in the DI, I discovered there was a lot of room to play with, and great latitude with detail at both ends [of the exposure range]. Since then, I have gone on to use Alexa on multiple projects.”

It was also a goal of Arri’s to introduce a digital camera with a 65mm large-format sensor — what eventually became the Alexa 65. Kraus points out that the company’s interest in large-format filmmaking was nothing new. “We won [a Sci-Tech Award in 1993] for introducing a 65mm sync-sound film camera called the Arriflex 765, which was very innovative,” he says. “But it was launched at a time when digital sound all of a sudden became mainstream — so that was the end of 70mm film distribution at the time, and it was not a big commercial success.”

But there again, Kraus notes, Arri’s interaction with the cinematography community during that phase paid off down the road. “We had that camera and shot many high-quality test reels with the best cinematographers in order to figure out the actual [resolution] limit,” Kraus says. “That got us thinking about when and how digital could look as good as film. I tried to convince [Arri’s] owners we should go for top-of-the-line. The result was the Alexa 65.”

Papamichael used the Alexa 65 on 2016’s The Huntsman: Winter’s War, “primarily for wide landscape shots, and operated off a 50-foot Technocrane on a daily basis. It was a great advantage to have all that detail in wide shots, which also allows you to extract portions of the frame, zoom in, and create small moves in post. The visual-effects team also really appreciates the extra image size.”

The arrival of Arri’s Alexa 65 in 2014, many cinematographers say, was yet another major advancement in the maturation process for feature-level digital cinematography. Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS — who won an ASC Award and an Oscar nomination for the 2016 drama Lion, directed by Garth Davis and shot with the Alexa XT system — has shot both 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (AC Feb. ’17) and Davis’ upcoming Mary Magdalene with the Alexa 65.

As Fraser recounts, soon after he was hired to shoot Rogue One, Ukas-Bradley invited him to Arri Burbank to offer a look at a new product. “It looked like an Alexa XT, but with too many donuts,” Fraser says. “I thought he was going to show me something small, like the Alexa M, and it seemed odd that he would show me [something that size] when I wanted a smaller camera. But he told me to take off the port cap, and I did. I was blown away by the size of that sensor.”

After his first look at the prototype, Fraser says, “I got on the phone with [Arri Rental] and they told me it was a camera for second-unit photography — [to shoot] plates for visual effects. I asked what the maximum frame rate was, and they said 30 fps right now, but 60 in a year’s time. I asked how large the files were, and they explained that they are four times the size of the Alexa XT’s files. Then I asked why you couldn’t shoot an entire movie on this camera. I got the camera and tested it — and the fact is, they had created a recording device of the highest standard, with the most amazing bit depth and resolution, to which I could then attach my favorite film lenses.

“I thought it was groundbreaking,” Fraser adds. “Until then, the only way to shoot 65mm was [with very large film cameras]. Arri created an evolution of digital with the camera, and they did it without knowing who would back it. It was the classic Field of Dreams theory — build it and they will come. So they built a 65mm [digital] camera and created a sudden wave of interest in that format. It is arguably the most important evolution in digital acquisition since digital came to the stage.”

Lubezki likewise “got very lucky,” as he says, by obtaining one of the first working prototypes of the Alexa 65 in time to employ it on The Revenant — under the most grueling of on-location conditions, with a natural-light-only aesthetic during winter in the mountains of Alberta, Canada.

The Alexa 65, Lubezki says, “was the only camera that could capture the environment the way that we physically felt it while we were there. We shot at dusk, when your eyes can barely see what is happening, and yet the camera could still capture the images properly at the most mysterious moment of the day. The language of The Revenant is very connected to that tool.”

Such an experience aptly demonstrates how the Alexa system has evolved into various sizes, applications and formats, in ways directly related to the needs of the cinematography community. Ukas-Bradley adds that from the beginning, the approach with the Alexa has been to build a technology that can grow and evolve in this way. “A key component of this approach is a very flexible electronic architecture based on FPGAs [field-programmable gate arrays],” he says, “which enabled us, in the case of Alexa, to become an industry standard over the last seven years. For example, initially Alexa was designed to top out at 60 fps, but by redistributing processing resources, we were able to increase the maximum frame rate to 120 fps. Integrating onboard ArriRaw recording — and just recently including wireless, uncompressed, low-latency video transmission for monitoring on our latest iteration of Alexa [the SXT W] — was all based on popular customer demand.”

Of course, cameras are hardly the full story. As it has done for decades, Arri continues to sell lenses and motion-picture lighting — and has enjoyed recent success in joining the LED revolution. Around 2005, Kennel relates, Arri started investigating multi-channel LED lighting, which eventually yielded Arri’s Pax LED units, a multi-channel, wireless system that could provide quality tunable light. That, in turn, led to the advent of the SkyPanel line, which is now a leading force in the company’s lighting division.

“We looked at LED and came in with four-channel technology,” says Pohlman. “It took almost 10 years from the first ideas to the [SkyPanel] product that was launched in 2014. That really changed our lighting division [over the last two years].”

Arri has come a long way since the company launched the first HMI lamphead, Arrisonne, for the 1972 Olympic Games, to go after the daylight market. Indeed, the company’s well-known success with camera systems and lighting sometimes masks just how diversified the modern iteration of Arri has become.

Pohlman points to “the Arri Rental Group, and our creative Arri Media division [that] now includes anything and everything related to postproduction — including sound studios, a small visual-effects division, and our DCP distribution company. [It is] a very unique position for Arri to support the whole postproduction pipeline — to be confronted with workflow challenges and to have the solutions implemented in the very top of the production chain with their cameras. And we also own a cinema of our own in Munich. So although we finally shut down our film lab [in 2016], we are basically still doing the kinds of things our founders started with back in 1917.”

The company also recently decided to revisit a market it stepped away from years ago, when Arri used to manufacture X-ray film cameras for the medical industry. The Arri Medical business unit is a small but growing focus for the company, according to Arri officials. The division has developed the specialized Arriscope, built on Alexa technology, which is essentially a digital microscope for ear, nose and throat surgeons. The device is capable of outputting HD image streams in 3D. “We hope to take that to neurosurgery and plastic surgery by next year,” Pohlman says.

As the company begins its second century, Arri continues to keep pace with the changing media-production landscape. Ukas-Bradley reports that company teams are investigating light-field camera technology, computational imaging, and various aspects of the virtual-, augmented- and mixed-reality arenas. And Kraus hints that more tools will be available in the near future for the filmmaking community. “You can expect that we will, for sure, have new products,” he says. “Both in the lighting and camera fields — very soon.”

Perhaps most importantly, company officials are working hard to expand and strengthen Arri’s longstanding relationships with the cinematography community. Kennel is particularly proud of a range of ongoing Arri educational and training programs — some of them in close cooperation with the ASC, like the ASC Master Classes in Toronto and Beijing.

“Our commitment to support the filmmaking community involves supporting film schools, and training camera and lighting crews that work with our equipment,” he says. “Arri Inc. also supports a filmmaker-equipment grant program for film students and emerging artists. Through this program we’ve supported projects like Beasts of the Southern Wild, Fruitvale Station, Imperial Dreams, Under the Gun and many more. We’ve introduced the Arri Academy, a hands-on training program for camera crews. And last year, we introduced the International Support Program, which provides support to emerging filmmakers around the world by integrating our entire portfolio — equipment rental, co-production, postproduction, film sales and distribution.”